Second in a series.

Unions have impacted every American worker.

From laws that curb the use of child labor to the 40-hour work week and holidays off, organized labor demanded – on occasion forced – governments and corporations to provide benefits and protections most people take for granted. In more practical terms, Charlotte’s transit system last week averted a work stoppage that could’ve made it more difficult for commuters to move across the city.

Bus drivers and mechanics – represented by SMART Local 1715 – ratified a new collective bargaining agreement with the company that manages Charlotte Area Transit System’s (CATS) bus system by a vote margin of 20 to 1. The contract calls for a wage increase retroactive to July 1, 2022, double-time for work during holidays and adds Juneteenth to the holiday schedule. It also provides night differential pay and increases workers’ pension cap.

As a nonprofit journalism organization, we depend on your support to fund more than 170 reporting projects every year on critical global and local issues. Donate any amount today to become a Pulitzer Center Champion and receive exclusive benefits!

“I would like to thank the negotiations committee … for their hard work and tireless effort to deliver a package that the members would accept,” SMART Transportation Division Bus Department Vice President Calvin Studivant said in a statement. “The negotiations took more than nine months to complete, but the committee stayed focused on the task at hand and they delivered.”

Although North Carolina law prohibits state, city or county government or taxpayer-funded agencies like CATS to negotiate with labor unions. RATPDev, the contract management company for CATS, handles collective bargaining with unionized workers.

“I am very thankful for the hard work that has gone into reaching this agreement," said Brent Cagle, CATS’s interim CEO. “This agreement aligns with our values at the City of Charlotte. It focuses on the employee, which is our most valuable asset. This new contract calls for significant wage increases, making our operator positions among the top paid on the East Coast.”

Even with greater awareness of unions and their activism, membership rates are near historic lows.

According to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, membership as a percentage of the national workforce fell to 10.1% in 2022, which continued a slide from 2021, when the rate was 10.3%. The number of hourly and salaried workers who belong to a union increased by 273,000 to 14.3 million, a 1.9% bump over the previous year, but the overall workforce grew by 5.3 million, or 3.9%, which accounts for the overall rate drop.

Employers, and every state government in the South, contend unions hurt businesses and stifle economic growth. Every state in the region has “right to work” laws that allow employers to hire and fire without repercussion.

Capitalism, business owners and advocacy groups contend, is better prepared to take care of workers and point to lower union participation as proof of their satisfaction.

“Unions are monopoly institutions that raise wages through collective bargaining, not productivity improvements,” Richard Epstein, Peter and Kirsten Bedford senior fellow adjunct at the Hoover Institution in Palo Alto, Calif., wrote in 2020 on the institution’s website. “The ensuing higher labor costs, higher costs of negotiating collective bargaining agreements, and higher labor market uncertainty all undercut the gains to union workers just as they magnify losses to nonunion employers, as well as to the shareholders, suppliers, and customers of these unionized firms. They also increase the risk of market disruption from strikes, lockouts, or firm bankruptcies whenever unions or employers overplay their hands in negotiation. These net losses in capital values reduce the pension fund values of unionized and nonunionized workers alike.”

Government workers make up a greater percentage of union members at 33.1%, more than five times higher than the private sector, which slid to an all-time low of 6%. The overall number of unionized workers is higher in the private sphere at 7.2 million than public (7.1 million).

Black workers are more likely to be union members (11.5%) than whites (10.3%) and 12.5% of Black men are members while 10.6% of Black women belong.

Unionization in the South, though, is all but an afterthought, which directly impacts compensation, benefits and workplace protections in a region where more than half of the nation’s Black population lives.

Racism vs. organizing

Throughout the 20th century, low-wage southern workers – especially Black people – were systematically excluded from labor protections and union rights extended to their northern peers.

During the 1930s and 1940s, when Congress passed the Fair Labor Standards Act and National Labor Relations Act as part of President Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal policies, southern lawmakers crafted legislative exceptions for agricultural workers, service employees who rely on tips and domestics – where Black people were more prevalent.

As a result of racist hostility upheld through slavery, Reconstruction and Jim Crow, the South has the lowest union density of any region in the U.S. at 6%. Accordingly, southerners are historically paid the lowest wages.

“Workers in the South face unique challenges tied to the legacy of racism that require a unique solution,” said Eric Winston, a restaurant cook from Durham and a member of the Union of Southern Service Workers which formed last November in Columbia, S.C. “We are building a union despite the fact that the rules are rigged against us as Southern workers. We are building a union by any means necessary and building it in a way that makes sense for us.”

Through collective action, USSW members pledge to confront the historic racism that excludes Black and brown workers from labor and minimum wage laws. Racial attitudes have also impacted attitudes on unionization. Throughout the 20th century, Business, political and bureaucratic leaders conflated labor with the civil rights movement, which were supported in large measure by unions.

During the Cold War, U.S. government agencies like the Federal Bureau of Investigation openly suggested Black activists with national followings such as labor leader A. Philip Randolph and civil rights advocate Martin Luther King Jr. were in cahoots with communists to undercut their advocacy.

Still, labor advocacy is part of Black history.

The Southern Tenant Farmers Union, a fusion of Black and white cotton workers, fought for higher wages and better treatment from landowners. Fannie Lou Hamer was a leader of the Mississippi Freedom Labor Union. Black hospital workers in Charleston, S.C., unionized and carried out a strike despite a state law that forbids collective bargaining.

“You have this group of working-class women who are challenging this notion that they can’t organize,” said O. Jennifer Dixon-McKnight, Ph.D., assistant professor of history and African American studies at Winthrop University who has researched the 1969 strike. “Their union can’t be recognized, but they have these issues. As working-class Americans, they’re trying to get equal pay, right? They’re trying to get just the basic respect.

“When we talk about that, and the value of workers being able to organize, but realizing that in the South … we still have a resistance to that sort of broad approach to labor and to labor organizing and labor unions.

“The question continues to be who do Black workers turn to? What is the resource, where are they supposed to get assistance? And when you think about this legacy of slavery, something that we don't often grapple with [is] the legacy of Jim Crow.”

Calling on Congress

Because southern states are bastions of right-to-work law, labor activism in the region sometimes leads to demands for federal intervention.

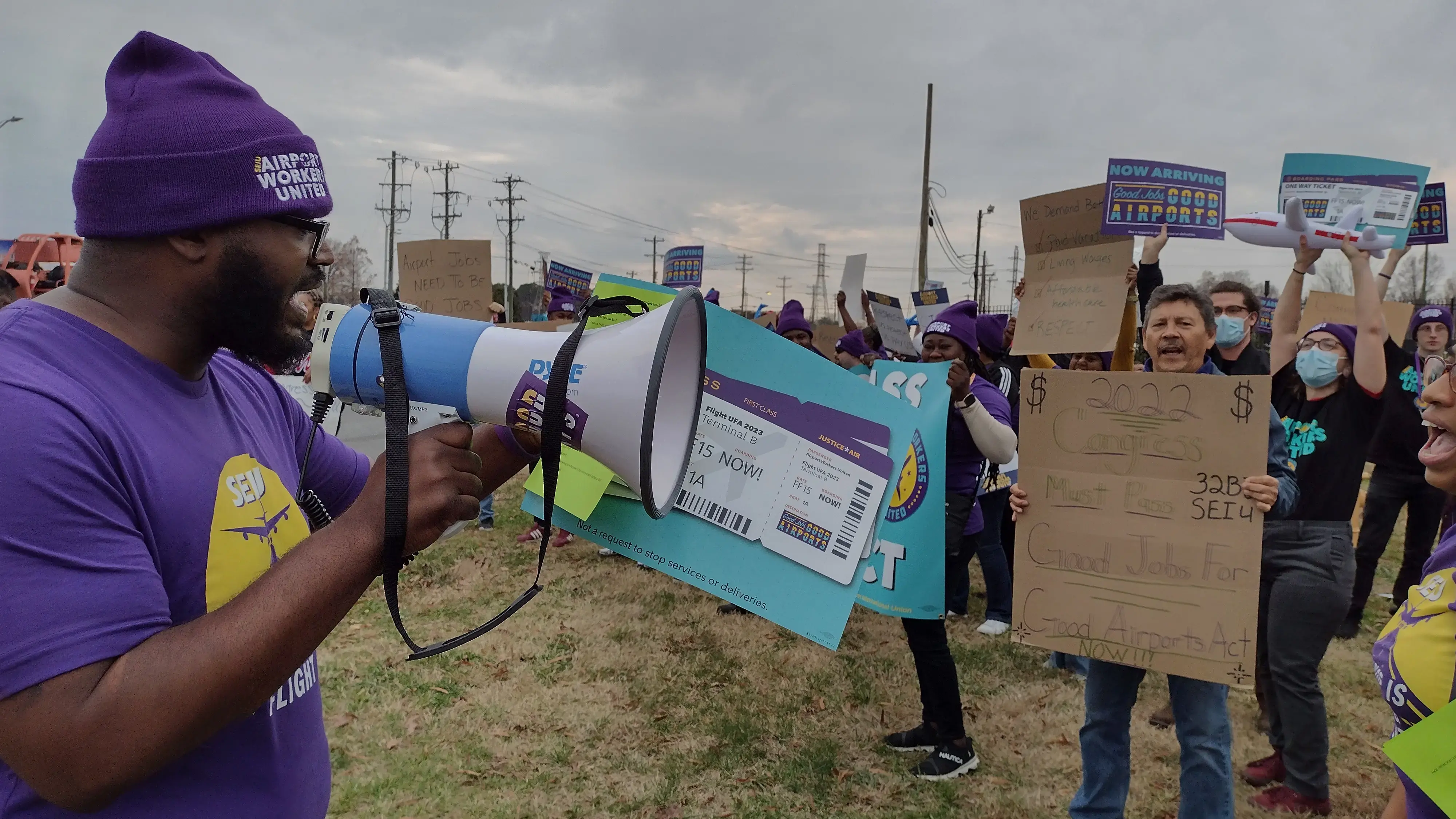

In December, service workers contracted to Charlotte Douglas International Airport lobbied Congress to pass the Good Jobs for Good Airports Act to ensure living wages and benefits like paid time off and healthcare.

During the holiday season – the most congested and chaotic time to travel in the U.S. – airport workers complained that staffing shortages, difficult workplace conditions made basic duties like cleaning aircraft cabins, collecting trash and handling baggage more difficult.

The Charlotte workers joined protests in 15 other cities organized with the Service Employees International Union, whose 175,000 members in 12 states include 18,000 contracted airport workers.

Without healthcare, paid leave and workplace protections, airport service workers - who say their wages have been near poverty level for 20 years - are at a breaking point.

“We’re working in 90-degree weather, carrying bags of trash that can weigh 70 pounds,” Shawn Montgomery, a cabin cleaner for Charlotte Douglas contractor Jetstream, said in December. “I’ve injured both of my knees coming down the steps and now I have to wear knee braces. Sometimes we don’t even have easy access to water. It can be dangerous when you're walking in the heat out on the asphalt.”

JetStream cabin cleaners said they often encounter vomit, blood, and human waste on the job but are expected to do their work quickly despite understaffing.

According to a 2017 University of California study, wage hikes encourage employee retention and airport security. The airport contractors say the Good Jobs for Good Airports Act will help stabilize airports’ workforce, security and move travelers on time.

“We’re short staffed because the pay and benefits are not enough for what we do,” said Shonda Barber, a JetStream trash truck driver who also fills in as a cabin cleaner. “I work 60 hours a week and am just barely surviving. We don’t get enough paid time off, even during the pandemic. I lost two weeks without pay when I had to quarantine.”

Even with increased advocacy by Black workers and awareness of labor demands, Dixon-McKnight believes change in the South will be incremental at best.

“We’re heading in the right direction, but I don’t think we will see meaningful change in our lifetime,” she said. “I think we’re still too close to Jim Crow. …When we talk about the sort of racist campaigns of the ‘50s and ‘60s and ‘70s, we’re only 50 years out, so that means that there are still people who carried out those kinds of things that are in power now.”