Ursula Bahillo could still be alive. The 18-year-old did everything she was supposed to. She filed complaints for gender violence against her ex-boyfriend, a police officer. She pleaded for help on social media: “If I don’t come back, smash everything!” But on Feb. 8 she was stabbed at least 15 times. Her ex-boyfriend, Matías Martínez, was arrested at the scene several miles outside the town of Rojas in the Argentine Pampas and charged with femicide (aggravated homicide). Prosecutors say he has declined to cooperate with the investigation; he has not entered a plea. His lawyer did not answer questions about the case.

Before Bahillo’s death, a prosecutor sought pretrial detention for Martínez on charges that he abused a minor in 2020. But the request came in January, midsummer in Argentina, when the court was in recess. Martínez remained at large. He’s in prison now for a separate crime: Two weeks after Bahillo was killed, Martínez was convicted of “aggravated minor injuries in connection with aggravated threats” against a different ex-girlfriend and sentenced to four years in prison. The victim had filed the complaint in 2017.

“Ursula’s case is the norm, not an exception,” said Elizabeth Gómez Alcorta, Argentina’s minister of women, gender and diversity. Argentina recorded more than 250 femicides in 2020, one every 35 hours. Forty-one of the victims had previously filed complaints. In the first eight months of 2021, the advocacy group Mumalá registered at least 118 femicides. In 13 percent of the confirmed cases, Mumalá estimates, the perpetrator was a member of the security forces.

As a nonprofit journalism organization, we depend on your support to fund more than 170 reporting projects every year on critical global and local issues. Donate any amount today to become a Pulitzer Center Champion and receive exclusive benefits!

Critics say police in Argentina have a problem with violence against women. In Buenos Aires province alone, the provincial police’s internal affairs division reported, gender violence complaints were filed against 5,965 police officers between 2013 and 2020. Eighty percent of those officers remain in uniform.

“Who will protect us from the police?” That was the question asked by thousands of women at protests in Buenos Aires after Bahillo’s death. The “Ni Una Menos” — or “Not One Less” — movement has been protesting violence against women since 2015. On some fronts, the pressure has made a difference: Argentina last year became the largest country in Latin America to legalize abortion (the supreme court in larger Mexico has since decriminalized the procedure there). The government created the Ministry for Women, Gender and Diversity. Children of women who are killed in cases of gender-based or domestic violence receive a small orphan’s pension. Micaela’s Law establishes mandatory training in gender issues and violence against women for all public employees.

But murders of women haven’t decreased.

Barbi Zabala, 20, was stabbed to death on Dec. 6, 2019. Her ex-boyfriend, a police officer, will stand trial as the only suspect. The attack was recorded by the public security cameras in the main square of the city of Pehuajó. Brian David Dirassar is charged with femicide. He has not entered a plea.

“The homicide is proven, and the defense is not going to deny it either,” said Fabio Cornejo, Dirassar’s lawyer. “What we’re going to be looking at is whether he actually manages to defend himself, if he is psychologically stable enough to exercise his right of defense.”

Zabala, like Bahillo, had filed complaints alleging physical violence. A no-approach order was issued against Dirassar; Zabala told police he violated it. A judge assigned a security detail to Zabala, but the protection was reduced to police cars passing by her home, her father says.

Óscar Zabala, Barbi’s father, is himself a police officer in Buenos Aires province. He’s a bomb disposal specialist. He asks himself how Dirassar was accepted into the police force.

According to La Casa del Encuentro, a Buenos Aires-based feminist group that works to end violence against women, girls, boys and adolescents, 214 women in Argentina were killed by police officers or former police officers between 2008 and 2020. “We take the problem seriously,” said Agustina Baudino, director of gender policies and human rights at the Buenos Aires security ministry. She’s responsible for familiarizing the 90,000 police officers in the provincial police force with gender issues, and organizes training sessions. She says more than a quarter have received the training.

The gender training focuses on how to work with victims. “You have to take a report!” psychologist Sandra Tomaino told 30 officers, male and female, at a session in Quilmes, near Buenos Aires. “You have to believe the woman. You have to do a risk evaluation.” The officers nodded. Tomaino encouraged the female officers to report colleagues if they themselves become victims of gender violence. In the past, Baudino said, female police officers were often unwilling to make a report because they worried it would not be taken seriously and feared they could be the targets of more violence from the colleague in question.

Patricia Nasutti, Bahillo’s mother, says change is necessary.

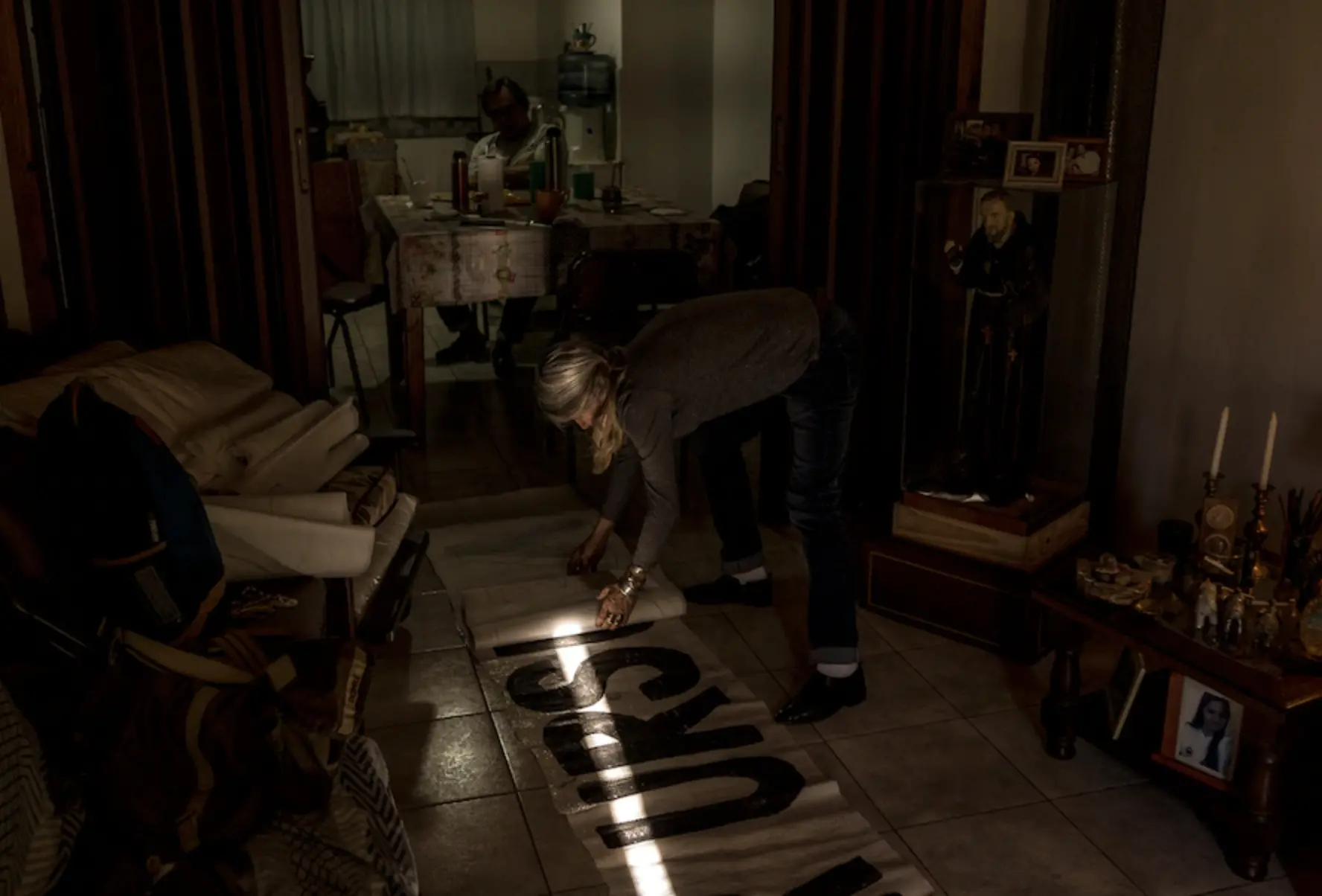

“My daughter left it written down: ‘Smash everything!’” she said. “Let them not smash flags, plants, police cars, glasses, chairs. Let them break the structures of what we are living.”