Of the 2.2 million that occupy the United States' prisons, many are facing wrongful convictions, lengthy sentences, or often a combination of both. For those behind bars, the means to find expression can be scarce. However, studies show that art can help those struggling with issues of self-worth, confidence, and empowerment.

On Tuesday, June 23, 2020, the Pulitzer Center's Talks @ Pulitzer Focus on Justice Series explored how theater can serve as a means of expression for the incarcerated. Pulitzer Center grantee and playwright Sarah Shourd interviewed Rhodessa Jones, director of The Medea Project: Theater for Incarcerated Women.

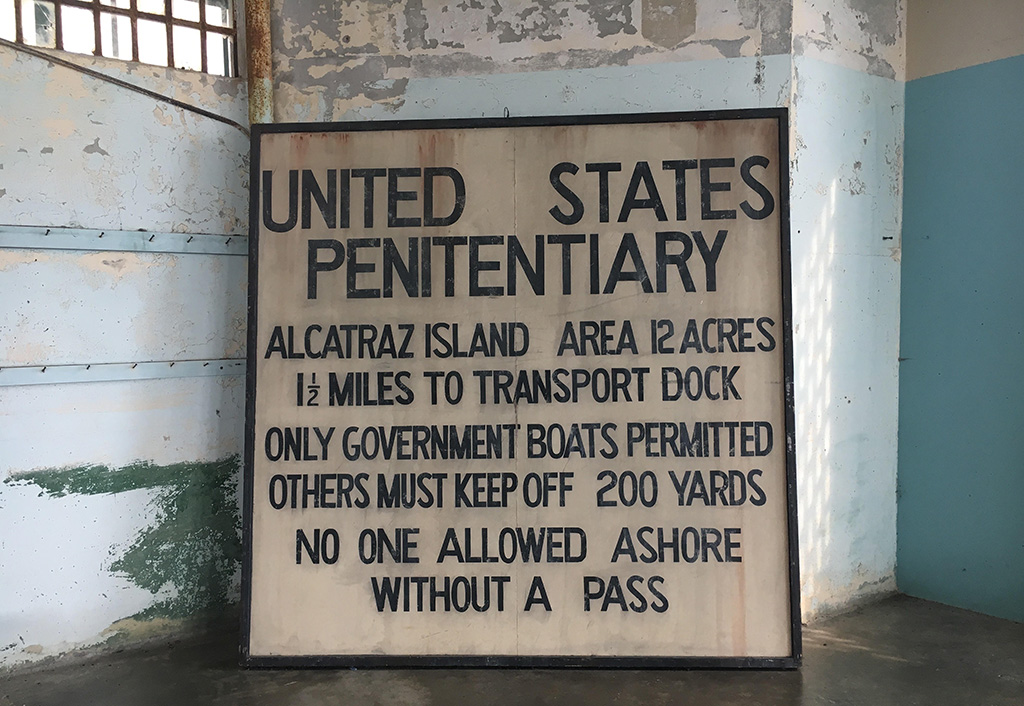

For the last 10 years, Shourd has worked to uncover the realities of mass incarceration and solitary confinement for audiences after spending more than a year as a political hostage in Iran. To read Shourd's reporting on the performance of her award-winning play The Box on Alcatraz Island, please see her project "Historic Performance of 'The Box' on Alcatraz Island." The webinar provides the backdrop to the forthcoming Pulitzer Center-supported virtual performance of The BOX, based on true stories of individuals in solitary confinement in U.S. prisons.

As director of The Medea Project, Jones has centered the experiences of incarcerated women in storytelling and explored the role of theater in reducing recidivism rates. She has decades of experience creating theater inside prisons. In addition to extensive workshops and productions in the United States, Jones has led The Medea Project in South African prisons and was recognized as an Arts Envoy by the U.S. Embassy in South Africa in 2012.

"Prison destroys life, and art can give it back," Shourd said.

The following is an edited transcript of the webinar, featuring excerpts from the portion hosted by Shourd as well as a question and answer segment. Portions of this text have been revised for clarity and/or length.

Sarah Shourd: In the spirit of collective liberation and love, we welcome you to this conversation about incarcerated women, collective trauma, racism, and healing that this country is in the midst of. Rhodessa, you've been working with incarcerated women for 23 years, and we're both artists in the business of telling stories that aren't often told. Can you tell us how your work gives women the tools to save their own lives?

Rhodessa Jones: First and foremost, my art, it's the kind of art that's life-affirming, it's not art for art's sake. One of the things that I found early on with incarcerated women was giving them a voice. So many women suffer indignations and such assaults because we don't know how to say "stop, this hurts me." When I went into the jails, I was so fascinated with all the women that were in lockdown and also the grist, a lot of them were very angry. Some of them had had 1,000-year-old eyes, but they were alive. So, it's like, okay, "what is this woman going to do?" I talked about my daughter just having gotten married and I was going to be a grandmother, and they were fascinated.

One, African-Americans, we're taught: don't be telling everybody your business, and people ask me, "well, why are you telling us your business?" and I said because I'm interested in how do we through sharing our stories, our experiences, create a road out of this place, back to our families, back to our communities? So, to answer your question, it all began with realizing that I gave them permission to speak, and with some prompts, basic prompts like, "what is your name?" "who gave you your name?" and women started to realize that even that was important. I met a woman in prison in Florida whose grandmother's name was Aretha, and I said, "If your grandmother's name is Aretha... the power behind the name... she's not happy with you being here. You've got to get it together girl and get out of here." And she was crying and laughing, you know, something as simple as that. Then in South Africa, I started to ask women, "How did you break your own heart?"

SS: Yeah, that question "how did you break your own heart?" we're gonna get back to because collectively our hearts have been broken for a very long time, and I think we're in a moment right now where America is looking at itself in the mirror, America is questioning itself, questioning the toxic murderous ideology of white supremacy, and there's an opportunity here for collective healing. But before we get deeper into some of these specific stories of the women you've worked with, I want to show a clip. Holly's going to show a clip from The Medea Project of some of these women and how came into these jails in the first place.

I've been lucky enough to see The Medea Project performed several times, and it's a feeling of witnessing and seeing a part of yourself being witnessed as a woman because I don't know a single woman who's not a survivor of something, and I came from a lineage of women that are survivors.

Can you talk about one woman in particular that has changed your life?

RJ: My goodness, which one? Was it Dina? Was it Cassandra? Angie? Angie is the young blonde woman who became my daughter. I mean, I met her in jail. She had been through it as far as drugs and a life on the streets, and at the same time, she was so open to the process, as well as, we did Pandora's box as a part of our show and she became, I think it was confusion was her character and she did this whole thing of walking back and forth and trying to answer the questions. And at the same time, she wanted to be near me, even when she got out of jail and was in a transitional house, she would... she would just be available to me. She was on the phone to me and for me, I realized, Oh my God, you are a panacea. You know, you, you have set this up, you have created this incredible holy ground. And there are people, there are women that are constantly reaching out for that lifeline.

And what does that make you, you know, Rhodessa Jones, and it made me grateful. It made me aware of my own power. It made me much more open about who I was, and also embracing forgiveness. You know, back to the time that we're living in right now, the other side of the open wound is that there are so many open hearts seeing George Floyd die like that on television during this pandemic when we're all in at home. America went, "Wait a minute! That's not who we are." You know, and our children, all of them are out in the streets, raising hell. Barack Obama said it appeals to our better angels. You know, and our country may be upside down, and leadership needs a lot of work, but the American people, you know, largely, are coming to the center of this very pulsating heart. Now the other side of it is the darkness, as my women in jail will tell you, you'll realize you've met the devil. And he's a very dull dude, Don't struggle with women. You're not ready. Women are far more dangerous than men, you know? So, what the country needs us doing what you and I are doing here. Sarah, sharing this talk, talking about it. I just want to go back to your piece, The Box. It was stunning.

SS: That's how we met.

RJ: Yes. That's how we met. And it was just like, I was like, now, here is a woman artist working with men and you just like created this. It was really huge, it reminded me of a dollhouse, the set did, and that we could look in and look out, and you got it. I don't know if that's just that as women, we hold everything. And I don't know what you went in and saw, I saw this configuration of incarceration and thought, this is what we can do. And I was just like blown away at the, at the art that you put before us, as well as the stories. So here we are, you know, here we are. And I feel like we were a part of the art activists who will... who are needed. Activists are needed if we're going to help people in lockdown, if we're going to help people in juvenile detention, if we're going to help people in mental institutions. I mean, the artist is the one with the vast imagination.

SS: Well, thank you for this. I mean, it was definitely one of the honors of my career to have you show up at the Z Space. That was the premiere of my play in 2o16 and you showed up with Senator Leno on your arm looking fabulous. Yeah, my work as a journalist and an artist comes from the unique life that I've lived, that all of us have lived, but with art and without the ability to express myself and connect my pain, I spent 410 days in solitary confinement 10 years ago when I was a political hostage in Iran, as you know. We knew that before, but we recently talked about it. You know, it's interesting because I was, like I said before, I was raised by women and my struggle has very much been my struggle for liberation and healing very much, been in the trauma unique trauma experienced by women as victims of violence by men, right.

And even prisons as an interest institution—largely politicians are men, largely the world is run by men and men are, you know putting women and men in prison. I know a little bit about your life. I mean, I've definitely, I've been reading up and watching videos about your work in prisons in South Africa and in Florida, but I don't really know that much about you Rhodessa as far as, like, I know you walked into that jail thinking you were going to teach aerobics in 1989 to women, and that's when you realized that's not what you were really called there to do at all. How has this work changed you? What has been your journey in doing this work for the last two decades?

RJ: Well, just to backtrack a little bit. You know, I was a mother before I was a woman, you know, I had a daughter at the age of 16 and thank God for my mother and father, we're talking 1965. I was living in upstate New York with my parents in the country. We had a dirt farm, so to speak. And my mother was very, very disappointed because my mother had had 19 pregnancies and 12 of us lived. And at the same time, there is this, there is a holiness about life, as well as the history of slavery in America that you know as a modern girl, I was going to go to Florence, Christian home and have this baby and leave and come back out and do what, but my mother saw me in a bathtub naked and she, she knew I was in a family way and went and told my dad. And I told them, "well, I'm going to give the baby away." My father said, "no, you're not."

He said, please. He said, "I realize you're young. You might have to go. But if I only have two grains of rice, that baby gets one and you get the other. And if you've got to go, you leave my blood. Don't you leave my blood here with us," you know? And so that was something very profound about that kind of support. And so when I went into the jails, it deepened the appreciation for my family. So when I went into the jails, I brought that with me and I would tell them, I told them the story. And so many urban girls were just fascinated that here I was sharing the story in a lot. A lot of women did understand it as well, but it deepened my appreciation for my own roots and where I came from.

And you know, I was just saying to a friend the other day black, black people, we're not monolithic. There's all kinds of black folks, you know, as like, as there is, but the rest of this callaloo called America. But I, when I went into the jails, it helped me to find my way, you know, I thought this is my work. There is something I know about this, that I might've been, I don't know if I was ashamed as much as I was just kind of stymied. Okay, I graduated high school because my mother Estella Lucy A. Jones said, "you got to finish school." She said, "you have a baby to take care of." Not even that you got to go to college, but you gotta finish high school, so I had that under my belt.

I was already dancing with a women's group. I was surrounded by Tumbleweed, which was a women's group started by Theresa Dickinson who had been a member of Twyla Tharp's company in New York. But she came to California. She wanted to collect it because she wanted women to make decisions. She didn't want to be the director.

So all of this is the stuff I brought in with me and also Idris Ackamor, who I just have to give a shout out to. He said to me, when I met him, he was my life partner for about 11 years. But when we started, we realized that we were onto something as a performing duo, as a very stable African-American nonprofit in San Francisco. He said to me, "Quit your day job." He said, "We can do this." And he said, you know, we, "but we have to just like change our habits. We have to get up earlier than usual." We have to be on the phone with, and he had already been doing this as a musician. And we started touring all the time, you know? And he gave me this incredible platform in which to stand.

And then another man in my life, my Irishman, he said, "Rho, you know everything," he said, you know, and he, Dennis John Patrick Reilly, he said, "Babe, you know everything there is to know." He said, "Don't be afraid of it, have confidence." So I brought all of that into the jail, even the love of two different, very different men, to share with women that it was possible. And of course my sisters, my mother, women, as you say, we know that circle, you know, and they have that kind of energy behind you, behind me, I brought all that into the jail. And even the spirits of my great-grandmother and both of them, the matriarch and the patriarchal grandmother. But I talked about all this stuff with these women, you know, I mean, we're talking crackheads, we're talking heroin addicts, we're talking boosters, we're talking paper pushers, you know, forgers. And all of a sudden we're talking about, we're doing kitchen table talk. And I think it touched on, it touched the memory, which is the name of my book I'm writing right now. It's Nudging the Memory. You know, to remember who you were before life came and before life hurts.

SS: Yeah, that's incredible. That's amazing to hear you talk about the men in your life that have given you support. I mean, in my play, and we're going to show a clip from that. Now, The Box is based on stories that I collected in solitary confinement across the country. And for me coming into, you know, a lot of the men that ended up in solitary confinement and women in this country, when there's 80 to 100 thousand on any given day, this is the deep end of our prison system. It's psychological torture, it's illegal under international law. And these are the most vulnerable populations, the same populations that you're working within your theater work, with mentally ill people, with substance misuse issues, people with a tremendous amount of trauma, or put in conditions that are exacerbating their trauma and driving them, you know, just to the very edge and beyond, you know, destroying them, driving them often to suicide or self-harm.

And what I also found is traveling to 13 different prisons across the country and interviewing men and women, I've found that people just had a tremendous amount of humanity. You know, I found men that are doing their work because that's, you know, they're at a place where all there is to do is think about their lives and think about their regrets and think about if they're given a second chance, what will they do with it? So, I was deeply keeled and moved by working with these men. And this is a clip we're going to show from a year ago. We did a performance on Alcatraz Island that the Pulitzer Center supported in the old penitentiary. And this is a scene where Ray Duval, the Black Panther character who's been in solitary confinement for 19 years is... really, he's saying goodbye to the four men in the pod that he's been with side-by-side though they've never seen each other's faces. So thank you. We'll watch this clip.

So that is Ray Duval's character, who's played by Damien Brown. Damien Brown himself was formerly incarcerated and he did over 20 years in prison, and now he's come out to be an incredible award-winning actor. Ray Duval's character is inspired by Herman Wallace, who I'm sure you've heard of, Rhodessa, one of the Angola Three, the three Black Panthers that were held in solitary confinement for over 40 years for a crime that they never committed. And these, you know, working with these men and hearing the stories of men, I think has been a tremendous healing for me around to see men that find love for each other and find a way to heal their own trauma and their own wounds. You know, men that society has failed on every level. There's a way that art can give this back to you, right? Prison destroys life and art can give it back. So can you tell me, what do you think is wrong with the way that the mainstream is telling the stories of incarcerated people or for that matter, Black and Brown people?

RJ: Well, I, I think because we get such double-edge, double-layered messages and even, you know, that was a rash of prison shows a few years back and they were all kind of, some of them, were rooted in the glamour of Hollywood, you know. That, you know, we as a public, we're hungry to know something, unless you, of course, if you're involved. You know, my brother was at Attica, so I, you know, long time ago before I was this activist, so I had a bit of a different kind of attitude about it, but I think it's people are led to be, even when you get arrested, you can be found guilty right away. You know, this is what happens with the death of them, the police, as well as some of us Black and Brown people, are not even visible.

Just an aside. I have a landlord that has never ever called me by my name. I've lived there for 50 years. This man has never called, never said, "Hello, Rhodessa." It's like, I open the door and he starts telling me what he needs or what I haven't done right. Or lately, I've seen him looking at me because of the news—Black Lives Matter—and all of a sudden, maybe I'm coming into view, you know, but we've been led as a culture and we need to believe this. One of the things about this American ability or a tendency to otherize people, you know, because it gives you some leg up. But as Toni Morrison says, "if you can only feel tall because somebody else's down on their knees, then you got a problem."

And we're at this place now. I think the artists going inside get to put these ideas out there, get to expand the imagination. You know, I've been in places where my visit has been cut short because the powers that be are afraid of what I'm saying to the men, you know, they're afraid that these monsters are going to riot. And at other places, San Francisco's county jail, Mike Hennessy was, he thought it was so important that with the women I worked with, at first I worked with men too, that they got to have some social interchange with an artist. But I think back to your question, I think it's just that it's easier to make up the whole damn thing, you know, then that gives those people in somewhat power reasons to lock people down and just, they're just never seen, that's insane to me, you know, the whole idea of solitary confinement for real, for that long, what on earth could you do? For that long, you know.

SS: And it's interesting, we're in this collective moment, during the shelter-in-place or self-quarantine, which is obviously ongoing. We're not at all out of this pandemic acknowledgment of collective safety. And at the same time, a critique of prisons and an acknowledgment that prisons were not making us any safer, right. Masquerading the public health crisis both before the coronavirus epidemic and during. I mean, prisons have become epicenters. You were talking to me this morning, we were talking about St. Quentin and some of the other places in California that are just exploding right now with coronavirus cases. And there's a collective, a moment of collective safety and collective struggle where people exploded into the streets after they saw the video of George Floyd's lynching. And that explosion was also an acknowledgment that we absolutely are in this together, right. And you and I were talking about all the new people in the moment movement, right? This wider swath of America, a lot more white Americans coming in, and you brought up White Fragility, the book that's now, number one on The New York Times bestseller list, I mean. You can definitely say one thing for sure: white people are reading. They're the top, the top 10 books on The New York Times bestseller lists are about anti-racism.

RJ: And let's hope they're talking to each other about the books. Let's hope that that's a discussion that's happening.

SS: But you know, this work is not for the faint of heart, the work of healing, the work of liberation. And do you, I mean, is there anything that you want to say about White Fragility or what you've experienced among the white people in your life that makes you concerned this moment is, is not going to have the, you know, longevity that it should?

RJ: Well, I am hoping and praying that the people who say they love me, white people... and I talk about white fragility in my own way. And I'm hoping that people that love me at least are listening or well, I had a dear friend who told me in all her magnanimousness love for me that she didn't see color, and I just let her have it. And no, she kept saying, "but I love you." I said, "That's all well and good honey, but you don't even know me if you don't see color." And I told her, "Don't ever say this again to a Brown or Black person ever," and she was just stunned that I sort of gave it to her, and I said, "Do you understand me?" I said cause I'm talking to you like this cause I love you. Is that what we're doing here?

Then a few years ago, I did a play at Theater Rhinoceros about race and segregation and prejudice. And it was with Black and white women. And most of the women that were in the play were coupled with another, with a Black woman or a white woman was with a Black woman or a Brown woman. And there was one lady that had a total meltdown as the story started pouring in about the abuse and the made to feel less than by the women of color. She got so upset and she just lost it and said, but it's not my fault. It's not my fault. And you know, and that was like, this was maybe 10, 15 years ago.

And she sincerely wanted it to be absolved of it all. And I said, what are we supposed to do, not talk, not hear them? Because you're feeling nervous and shaky and guilty. But I just want everybody, I said, "We get it. You're here with us. You're laying with a Black woman. So we get it." But understand that you've benefited from this terrible thing called slavery, called oppression, called domesticity at its darkest. You benefited from it. And I think, but God bless women again, we did, I think maybe we heard each other easier than sometimes a mixed group, a coed group of people.

SS: White people need to do their work. Anti-racism is not just like a class you took in your twenties and you're done.

RJ: It goes on and on and on, you know, and you gotta be, you gotta hear it. You gotta hear it, yes.

SS: Absolutely. So this next clip that I'm going to show is about that. It's about, you know, doing your work is not easy. And it's... it's not for the faint of heart. Here we go.

Yep, beautiful. So we're going to move right into the Q&A because we've got some amazing questions. Kayla is asking, "In what practices or daily habits are you both finding strength in recently?" Which reminds me of the question that we asked each other in one of our dialogues on the side of, you know, what have you discovered in this moment during the pandemic, during the shelter-in-place that you're reluctant to lose?

RJ: The peace and the quiet. I love the quiet of what this time brings for me, but, but I'm 71 years old. So, I've been out there. I had a good time, you know, and I don't want to deprive anybody of that, but the quiet, the solitude with myself is one thing that I will miss because, you know, we got to, you know, in our work. Both of us, it's like, going in and out of prisons and those particular places, it can be so tumultuous. Yeah. What is it? What is it for you?

SS: Well, it's similar. I think that I found at a much deeper spiritual practice and able to, I think I'd mentioned to you before, I was reluctant to really confront, to really face my whiteness and look at my ancestors. You know, my grandmother, may she rest in peace and power, was a brilliant artist and a pianist. And she was also horribly racist. And my grandmother was an immigrant from Ireland and she was you know, she saved my mother's life as a child, and she was also horribly racist. And to hold these contradictions and to sit with that pain, you really need a spiritual practice. You really need that solitude. And for me, it's been a long, 10-year process of reclaiming that solitude because in prison that was torture, you know, that was used to break me, tried to, so this has really been a full-circle moment of circling back to my essential self and being able to, to face what I need to face. So we have another question coming in about, "How did you find your connection to art and when did you understand how to use it in your activism?"

RJ: My grandmother, my big mama, my mother's mother. That's how she taught us. That's how she guided us with stories, with parables. I knew long ago... I knew about Uncle Remus long before Disney. My, you know, the Briar patch. And also she had this whole handle on the fairytales. Do you know what I mean? She told us about the, you know, the main pig hanging up the laundry and the crow pecks off her nose. I mean it was crazy, but my grandmother was an incredible actor, but there were so many of us, my mother and father were working, and this was my early beginnings. And also it was my way to like seduce, all kinds of people or white people being out in the world cause we were migrants. So, my family, we were all over the Eastern seaboard. So you'd have to, you'd end up in schools with just white people sometimes. And you have to be just a little bit more clever and you'd have to be, and knowing that you were just a bit more real. And so that was the early beginnings of my performing, telling stories was a way to weave a certain kind of magic way to seduce people, mesmerize people.

SS: And that's connected to another question. Rachel Dickstein wants to know about the origin of the name, the Medea project, and the connection to Medea.

RJ: How much time do we have to answer? Now, when I started working in the city in the San Francisco city jail, Bryant street, I had been asked to come in and teach aerobics to incarcerated women. I had actually gotten this decree down from the California Arts Council, God bless them. They just, knew so many women were going to jail. They were trying to figure out what could they do in support of women in lockdown. So, I went in and I would gather the women on Mondays or Wednesdays or Fridays. And I would go to all the cages on the seventh floor on Bryant street. And one day, I wandered to the back of the seventh floor where there were women in cages and that was a woman named Deborah sitting there. And she, she was already on the moon and I'm, you know, I've got my extensions, I'm being fabulous and I'm being up and I'm like, well, this is your life. I remember I said "you want to come to the gym," blah, blah, blah, blah, blah. And she, all she would say is that only God can judge me. And she was looking far away and I'm like, huh. And she says, "I'm waiting for God. I'm waiting for God to come and tell me which way to go." So, I went back to the desk and they told me that this woman had actually murdered her baby in a cocaine hallucination fury fight with the father. The father had said, "I want you gone."

And they were doing coke, and he realized that she had really developed a bad habit, not to mention this woman had graduated Berkeley. She, you know, and all of a sudden she's during the day, he was driving buses or whatever, and she was out, you know, scrounging getting more cocaine. She had gotten really strung out and he found out about, and he said, "I want you gone. I only want my baby out of here. I want you gone." And she said okay, and he stormed out and she said, as Medea, if you know anything about Greek classics, she smothers the baby. This woman says, well, you know, watch what I can do. You know, which is the final frontier. And she does this and this is, I heard this story. And I had already been interested in Pasolini's Medea. And I'd been interested in A Dream of Passion with Ellen Burstyn. So, all of a sudden, this Medea character is in my face again. And I, and I knew that it was going to be called The Medea Project because of where women had been, the darkness that they had, the rabbit hole that they had fallen into. So yeah, it grew out of basic knowledge of the myths, but also hearing a live, hearing a story that was really alive, yeah.

SS: It's unimaginable to try to imagine the depth of unbelievable pain to live with having committed that act. You know, this other question is, all the questions are just perfectly delving the stories you're telling, but Kayla wanted to know, "How do you find the strength to hold such difficult stories? How do you find the strength to hold these stories?"

RJ: Well, they strengthened me. I'm incredibly empowered because I am privileged to hear them. I found mechanisms that women will share anything with me, but once, I had the great privilege of being on a panel that Alicia Garza at Hamilton College and someone asked her about, you know, self-care and she said, "I'm not interested in self-care. I'm interested in collective care." And I thank God for my Medea crew, The Medea Project Theater for Incarcerated Women because they are there to hold me up. They're there, they pay attention. They pay attention to me. They pay attention to my need to chill out, you know, and they will tell me, so, you know, and I need that. I need other people that are willing to step up, but largely I'm so glad that this is the work that found me, you know? Yeah.

SS: Oh yeah. And I would say the same thing, you know, the people that I work with. I mean, working with men that have, you know, some of them don't deserve to be in prison and have never done anything wrong other than just be hurt people that, you know, made a mistake and never got a second chance, and others have done violent things. I've heard people and carry a tremendous amount of remorse and pain and redemption, and working with these with men and getting to know men that, that are doing their work of healing, has been healing for me. You know, if you encounter men inside prison that you just don't see on the outside. Really people, men that have, have looked at, at parts of their nature, that, that a lot of men, or people for that that matter, never have, and have confronted their own pain. And that gives me a tremendous amount of healing and strength and ability to, I mean, to continue to look at.

So we'll ask one more question or two, cause we have about five more minutes. Catherine Nye wants to know, just talking about this conversation about violence prevention and defunding the police and how the reforms have not been enough, right. But the police department is not at all where it needs to be. We're in a place where we're absolutely confronted by the utter failure of police departments to keep us safe. I mean, I recently read this, hundreds of thousands of rape kits that are untested know warehouses across the country that the police say they don't have money. The police never should have been given the responsibility of these rape kits in the first place. So, have this conversation about working with prisons, you know, and against the prison system and the police department. Is there anything that you want to say about that Rhodessa?

RJ: Well, I was speaking to a friend about after George Floyd was buried and it was like, okay, now what did we do? This is what the pundits were saying about with all the children in the streets. And I think the leadership will have to take the young back to the very beginning, you know, a Black, all of the things, all of the services that were either ignored or failed us, you know good housing for everybody, a great education for everybody. You know, looking at mass incarceration from all those sides, because I was saying to some young people that the death of this man really speaks to mass incarceration and that so many things were thrown to the side and the police. And I mean, I had police in my family, but largely the modern-day ideas that a lot of them are legalized gangs, and they're terrified of the people that they are really overseeing, not even like servicing, they're overseeing these people and they're terrified of them. And also it's the only place they have any power. And all of that has to be this has disseminated and has to be looked at, you know, with, I think, community groups. We need to start back with community review, review boards with young people, with all this passion. It can't be politicians that can be bought off, and it's gotta be social workers. There's got to be, you know, people that are here in the name of psychological, spiritual service, that has gotta be a large that... I think, there should be a large community review that's made up. Defunding the police means that we have the... some of this money to bring in people to take it apart and look at it, to talk about racism, to talk about fear, you know, to talk about. Most men don't know what a woman is—they throw rape kits away? Good lord.

I'm saying, give me a break. You know, and I think that we have to just like to start anew. As my friend, Seiko Sundiata would say, "learn the history, get with the history of rocks and stars, get with the hard facts of the planet." And you know, we gotta go all the way back and take this thing. The civil rights era is a good place. The beginning of the civil rights movement is a good place to start taking things apart again, and everybody participating and admitting where they, where they came in and where they didn't come in, or you know, dealing with white fragility dealing with all lives matter. Yes. But if we can get Black lives to really matter, it can stop a lot of our problems.

SS: Absolutely. And so this is connected to Caitlin Roberts' question about whether either of us would call ourselves an abolitionist. And I do consider myself to be an abolitionist in the sense of, that is the world that I orient myself to. That's where my moral compass should always be directed. And really that word, the vision of a world without prison is what keeps me trying to expand my imagination, because I struggle with it. You know, people in my family have been victims of violence, I've been a victim of violence, and I want those people to stop hurting other people. And until there's a solution, I'm not going to say that I never support anyone going to prison. That have directly hurt people in my family, that I support being in prison for now, until there's a better solution. I try to just orient myself towards the doctrine of "do no harm," but that said, you have to constantly be reminded that the vast majority of people in our prisons should be in mental health services, should be in system or substance addiction programs. And that prison is not fixing any of these systemic problems, it's only exacerbating them. So we need, right now, people are saying, "These incremental changes are not enough." We're running out of time. We have to think of holistic solutions. And that's what abolitionism asks us to do.

RJ: I think I concur, but I'm an artist-activist, I really believe in art as social change, you know, it's just a way to create a circle and we all start sharing stories, you know, and let us begin from there, you know. And then Richard Pryor, the great comic said, "Some folks belong in jail." So yeah, we have to keep that in mind too.

SS: Thank you, Rhodessa. What a joy.

RJ: Thank you. It's been a lovely, lovely time. Thank you so much. Thank you.

To learn more about the theater, art, and incarcerated people and how you can support them, see the resources below:

Books:

- Theatre In Prison: Theory and Practice by Michael Balfour

- Razor Wire Women: Prisoners, Activists, Scholars, and Artists by Jodie Michelle Lawston and Ashley E. Lucas

Films:

- Soliloquies from Women in Prison by Louis Anajjar

- Concrete, Steel & Paint by Cindy Burstein and Tony Heriza

- Making Me Whole: Prison, Art, and Healing by Connecticut Public Television

Organizations: