It is the ninth performance of the world premiere of my play, The BOX, and the screaming and banging has been getting to me. My play, based on stories I collected from people in solitary confinement in prisons across the U.S., was a culmination of years of investigative work. Thus far I’ve been in the audience to watch every show, but this time I decide to sit one out.

I’m out in the lobby with my eyes closed and feet up, listening to the muffled yelling of actors on stage. About twenty minutes into the performance I hear footsteps coming from behind me. I open my eyes just in time to see a figure rush past, heading toward the front door. I see a tall man in his thirties, with mid-length curly hair, wearing a baggy T-shirt and pants. It’s then that I notice his clothes are wet. I realize he’s literally drenched in sweat.

Wait, I say, standing up.

The man already has one foot out the door when he turns to look at me, his eyes darting back and forth.

Are you all right? I ask, walking toward him.

He glances down at his clothes then looks up at me.

This has never happened before, he says, I don’t know why I’m sweating like this.

He tells me he’s never been to prison, and he has no idea why a play about solitary confinement would provoke such an extreme physiological reaction. He reassures me he has somewhere safe to go, that he won’t be alone. Then, after less than a minute, he’s gone.

As a multimedia journalist, storyteller and artist, I’ve learned a lot from playing with form. I’ve told stories based on my own investigation into solitary confinement in U.S. prisons in mediums that span from traditional print journalism to immersive theatre, and now a graphic novel.

Each time, I’ve found the impact my projects have had and the audiences they’ve reached have been distinct. This has shown me how flipping content into different creative forms can be strategic and focused, a way for journalism to reach widespread, diverse, new audiences and have the impact our stories deserve.

Audience: Who Does It Reach?

While I was a John S. Knight Fellow at Stanford in 2019 I had the opportunity to collaboratively create a graphic novel (Flying Kites: The 2013 Prisoner Hunger Strike) that drew heavily from my own years of research on solitary confinement. In addition to being less visceral, graphic novels also appeal to a very different demographic, often young adults or teenagers. Take, for example, Arthur Van de Weghe, an eleven-year-old from Belgium whose father gave him a copy of Flying Kites.

After reading our book, Arthur wrote the following, “I really liked reading your graphic novel because now I know how inhumane solitary confinement is. I will never forget how creative inmates can be to survive by using ropes to pass letters and trade food under their cell doors. I recommend everybody read this book!”

A graphic novel is a very different container for story than theater. The figures depicted are not live actors in the flesh, they are small abstractions on a page. The format itself is more distancing, with various snapshots of a scene separated by space on a page (called “gutters”) that the mind is forced to string together into a cohesive narrative.

When story is immersive and intense, some people have the reaction of wanting to push it away. For example, after seeing The BOX on stage, some audience members felt so shell-shocked that they came up to me during the intermission with ashen faces: Is it really that bad? they’d ask. Are you sure this isn’t exaggerated?

Of course, no two viewers will ever react the same. Others approached me after the show with huge smiles and high fives, many of them formerly incarcerated individuals who experienced validation from seeing their lives depicted accurately on stage, rather than cognitive dissonance or disbelief.

Although graphic novels are generally not as visceral as live theater (it’s a stretch to imagine a reader sweating profusely while reading Flying Kites), they are powerful in another way. They create a safe container for the reader’s imagination to occupy.

A parent can give a graphic novel about solitary confinement to their preadolescent child (depending, of course, on the particular child’s specific needs) without excessive fear of nightmares or distress. Likewise, an adult who might sit out a play on solitary confinement, perhaps due to lack of time or lack of an emotional commitment, might be more inclined to give a graphic novel a shot.

In the private, intimate world of pen and ink, each reader has the privacy to find a unique path into the characters, understanding their motivations and inner world through his or her own. It can provide just enough distance from disturbing material to make space for critical thinking and empathy to grow.

Scale: Where Can It Go?

Our stories can’t have impact unless they reach the people who can use them, the people who need them the most.

The first production of The BOX reached over three thousand viewers, many of them people who had no direct experience with the prison system. Many reported being deeply affected by the experience, even years later. Though theater may pack a visceral narrative punch, it has a design flaw in that it is very expensive, involving heavy sets and physical bodies, and therefore difficult to scale.

Graphic novels are also expensive and labor-intensive to produce, but unlike theater, once they are published they can go almost anywhere. The books I’ve worked on about solitary confinement (see Hell Is a Very Small Place: Voices from Solitary Confinement and Sliver of Light: Three Americans Imprisoned in Iran) have been translated into other languages, excerpted in magazines, used in classrooms and adapted into short films, as well as being referenced in many other works. We have sent copies of Flying Kites to Russia, to Jordan, and perhaps most importantly, to hundreds of prisoners in solitary confinement across the U.S., back into the prisons where the real stories began.

It used to be that mass media, mainly television and newspapers, was about reaching as many people as possible. It didn’t matter who they were because the underlying belief was that, in a democracy, all people needed the same information. But the internet has exploded that belief while at the same time inspiring specialization and a more audience-centered design approach. A journalist’s reach can now be strategic, almost surgically focused, on the audience that needs a particular story the most.

Choosing the right container for a story means we’re no longer hurling stories into the dark. We can hone in on a specific demographic, profession, community or geographic region. We can start by asking ourselves what audience needs a particular story the most, what medium they favor and how our story, and the information contained within, might impact their lives in a meaningful way.

In addition to traveling across physical space, story can travel across social, identity-based and geographical bubbles, as well as bridge divisions in our own minds.

Impact: Who Does It Change?

Early one morning in 2016 I’m sitting in Michael Krasney’s studio at KQED in San Francisco being interviewed on Forum, a radio show that has been airing in San Francisco for almost three decades. We’re nearly at the end of our month-long run of The BOX, and I’m talking about the different audience reactions we’ve been getting, from shock to empowerment, when Krasney decides to bring in a caller.

The woman on the line had just seen the play. She encourages everyone listening to go see one of the last performances before it disappears. “It’s not an easy experience,” she warns, “but it’s an important one; after all, how often does a story change you?”

This question stuck with me, and it’s one I’ve examined a lot, particularly during my year as a JSK Fellow at Stanford. My conclusion is that stories change us a great deal. Studies have shown that a good story travels directly to the part of our brain that processes lived experience. Story is already a bridge, traveling the very short distance between “us” and “them,” so that an experience that was once alien to us now feels almost like our own. Stories influence our behavior, the decisions we make little and large. Stories may be one of the main ways we humans evolve, and one of the main hopes for our future on this planet.

For many people, journalism is about the facts, and it’s no doubt an essential part of the profession that our work be rigorously researched, sourced and fact-checked. But stories themselves, especially true ones, also contain information about the world-facts-albeit from an arguable, more subjective point of view. Stories, for example, of how prisoners in isolation are resisting the inhumanity in their conditions in California can provide valuable information to prisoners in Colorado or New Jersey facing the same or similar obstacles in their lives. In this way, stories can give people ideas, provide inspiration and even spark action that can improve their lives, reduce suffering their communities and help create a more meaningful world for all of us.

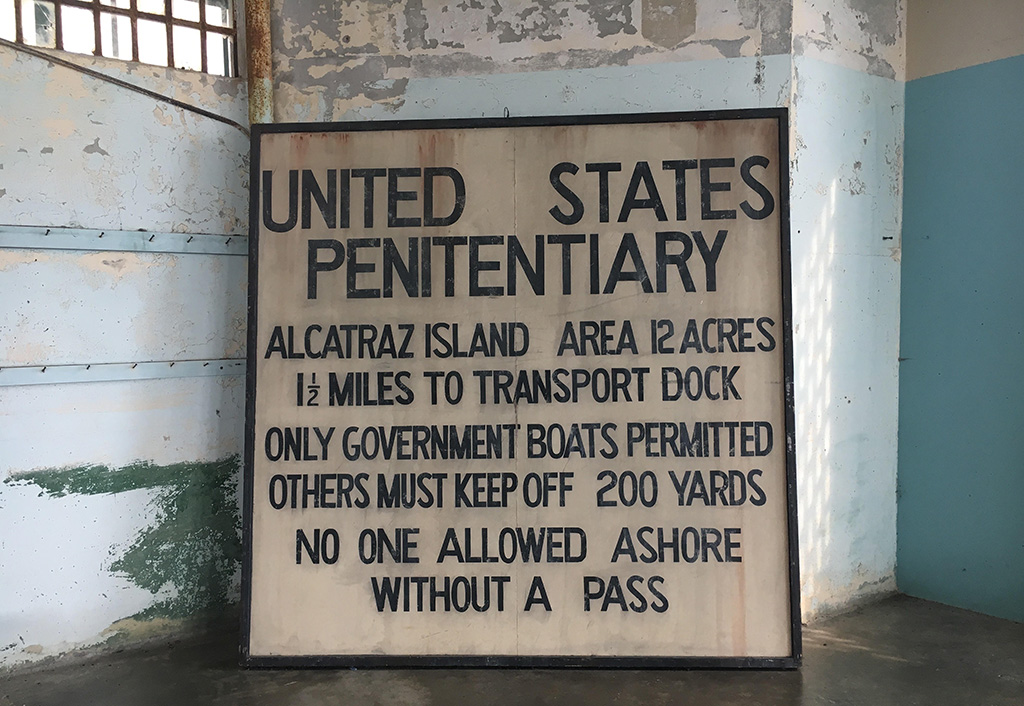

The second full production of The BOX was performed on Alcatraz Island in the San Francisco Bay, the site of the infamous penitentiary that is now a museum and tourist attraction. The circumstances were entirely different from the multiple productions of two years earlier. It was incorporated in a year-long exhibit, “The Future IDs of Alcatraz,” and from the get-go the curator of the project, Gregory Sale, set an intention of reaching the people most affected by incarceration. That meant The BOX didn’t need to be a loud bang that would rouse an audience removed from the reality of incarceration out of its slumber into action; it could be quiet, reverent, an opportunity for collective healing and collective witness.

The result was a very different production: a smaller cast, bare-bones set, limited screaming and banging and the words themselves performed at spoken-voice level (partly to avoid disturbing a semi-endangered bird species, Black Cormorants, mating outside the building; after all, we were performing inside a national park).

This production gave the audience an opportunity to lean in and really listen: to the waves crashing outside, the long silences, and perhaps even the voices of the people who had once been brutalized in what was now a beautiful place. It gave the words — and audience — space to breathe.

After the show we formed a circle, and, one after another, audience members, many formerly incarcerated, shared more deeply than I’d perhaps ever witnessed after a performance. I was reminded that the shape and texture of the container we pour our stories into changes what’s inside.

The medium is the house in which our stories live.