For most of us watching, it was as close as we will ever be to the brutal reality of endless days in windowless cells. For some of those on stage, it was a direct reflection of their own past.

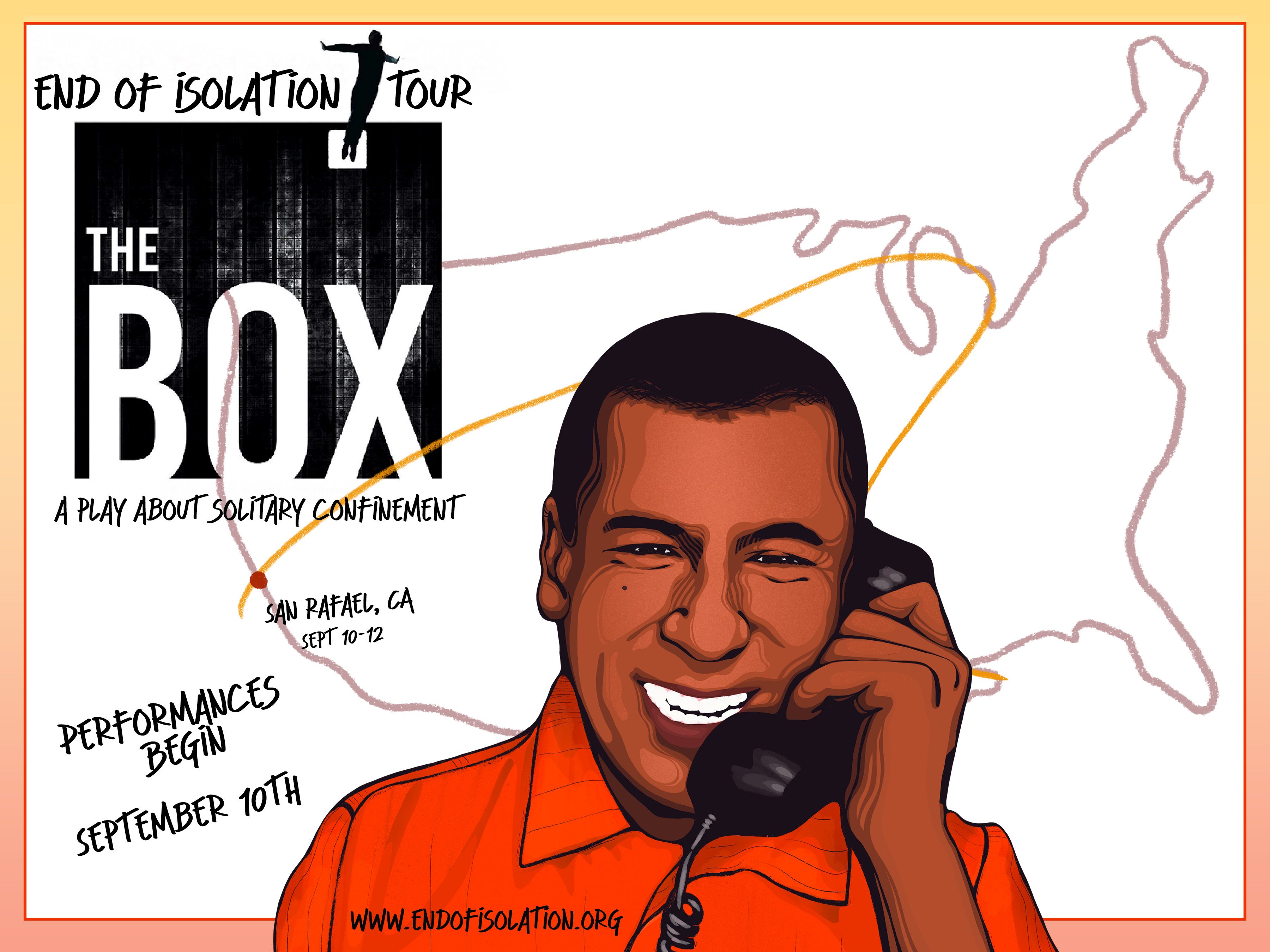

Over the course of two months this summer, audiences across the country were riveted by performances of The BOX, grantee Sarah Shourd’s soul-shaking exposé of solitary confinement in the American penal system.

“I cannot recall a theater experience that had a greater lock on the conscience of its audience,” wrote D.C. theater critic John Stoltenberg. “It was not just good theater, it was phenomenal.”

In the 10 cities where the 25 performances took place, from Austin to Detroit and on to Philadelphia, Washington, and Atlanta, Shourd and her acting company worked with community activists on local campaigns for criminal justice reform. In four of the cities, the Pulitzer Center's education staff led workshops and other engagements for teachers.

Anthony Michael Jefferson, one of the actors, drew from his own experience of long periods in solitary confinement. For another, Gabriel Montoya, chance encounters in every community drove home the unspeakable number of people who have been scarred by an unjust justice system.

What follows are their essays about taking The BOX on the road.

The Bumpy Road Less Traveled

By Anthony Michael Jefferson

As many adventures begin, it’s a friend helping out another friend. Well, this journey began in just said fashion. My former dorm mate at Avenal State Prison gave me a call from his desk at “Dad’s Back Academy” in Los Angeles, California. The year is 2020, and Osbert Owour and I were two of too many people incarcerated for life-term sentences, warehoused at Avenal during a turbulent time in a Level 4 prison.

Level 4 prisons house some of the most notorious prison gangs, street gangs, groups, and individuals in the California Department of Corrections.

I was serving a 25-to-life sentence, and Owour was a juvenile offender who, at the age of 16, was sentenced to 20 years to "double" life. When I was sentenced, it was 1992. Take a moment to wrap your mind and imagination around what I’ve just shared with you.

Now as we continue down this bumpy road less traveled, I’m going to ask you to think about the improbability of this journey. The statistical data that points toward impossibility. Now for s---- and giggles, understand that Owour is the point of connection that gets me introduced to Susie Tanner of the TheatreWorkers Project.

Susie, along with the Further Shores Project team, created a visual piece via Zoom that conveys the willingness of the formerly incarcerated to be vulnerable—confronting themselves and their devastating actions, the reaching effects of which weaken the fragile threads of society.

A sidebar, if you please. Transformative justice, restorative justice, and the willingness of all parties that manufacture laws that keep a large number of Black, brown, and those immigrants who’ve come to these illusionary distant shores seeking …

Allow me to introduce an alarming stat. Since 2009, the fastest-growing group of people being imprisoned (warehoused) are women.

Another phone call is made, this connection has never been made crystal clear to me. Sometimes you just give thanks knowing that not every detail needs to be Waterford clear, can you dig it?

Enter Sarah Shourd. Ms. Shourd is many things. Words pop into my mind like Jiffy Pop Popcorn on a gas range: survivor, talented, charismatic, humble, courageous, and visionary explode with vibrant colors.

The End of Isolation Tour (EIT), it's very name a phrase that always catches my breath as I reflect on my journey with it, took us to 12 cities, 25 performances, and, up to this point in my returned citizenship, a journey that can only be described as a dream come true.

Allow me to pose this question to you, my curious readers: Whose dream is it? Sarah’s or the various players of which there are many? These players and their individual dreams, hopes, and desires are spread far and wide. They are former judges, impacted family members, and weary members of society who see their tax dollars being misused for privatized prisons.

Mass incarceration is a well-thought-out system. Solitary confinement is a torturous, dare I say, criminal act carried out by women or men “who’ve become either indifferent or sadistic,” a line from The BOX.

On the bumpy road less traveled, we—the bright-eyed, naïve band of nine multi-talented persons of various pronouns—came together with a single breath of belief. We can do this! Something none of us actually had ever done. Such is the power of community, and such is the power of faith.

Faith brought the skilled members of the Burning Man Society together to convert a 40-foot bus to use on the tour. Faith brought that bus—or “Big B,” as it was affectionately referred to—along with its driver, Rob Connell, and core members of the EIT from Oakland to as far south as Atlanta, Georgia. How they maneuvered us throughout points in between speaks to the magic of legislative theatre.

I had three weeks to sit with, assess, and create a list of what I did right, what I did wrong, and how I was transformed by submerging myself into a collective dream that was the EIT.

The EIT held adventure, trials, and tribulations, which are now indelible in my spirit, mind, and heart. The bumpy road less traveled is and will be forever more a time that lives in my bones. The tumultuous route from San Raphael, California, to “Hotlanta” was hypnotic, healing, and effective at its very core.

In the efforts of the seen and unseen, a positive ripple rolled lumber and at times got off course. Perseverance, patience, love of the craft, and a belief in one another created a provocative question for you, my thoughtful readers: Are you willing to advance legislative theatre, are you individually and collectively willing to raise your voices—literally and financially?

It’s not every day that one is selected to take a fantastic voyage, but every mile on this journey changed perceptions and hearts.

It takes special individuals to take on the bumpy road less traveled! I’m willing to wager that the more of us who do, the better our justice system will begin to evolve.

Because of the EIT, performing in The BOX, and meeting many impactful community partners and all the faces behind the scenes, I am transformed.

A View of Mass Incarceration From ‘The BOX’ on Wheels

By Gabriel Montoya

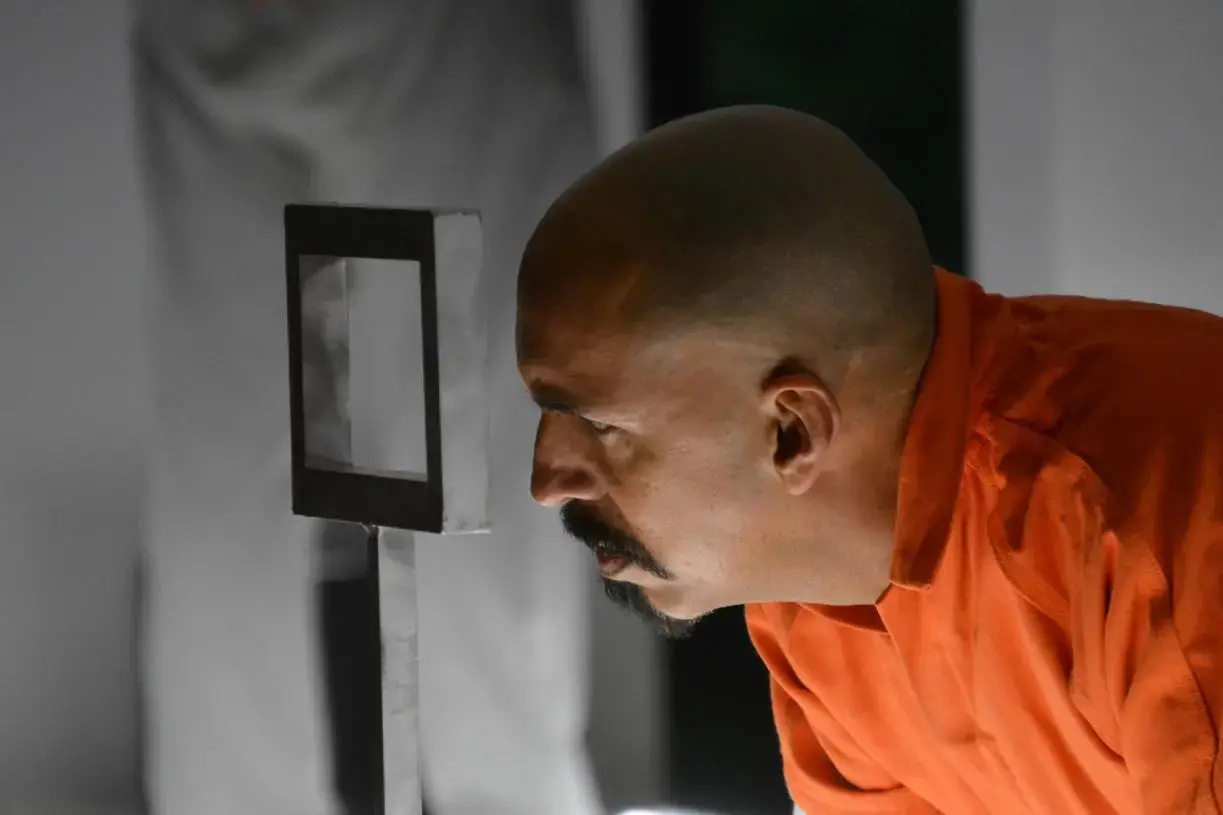

My name is Gabriel Montoya. I am a Mexican-American actor-director-writer from California. This summer I played Victor Santiago in Sarah Shourd’s stunning play The BOX, the centerpiece of the End of Isolation Tour presented by the Pulitzer Center that brought performances to communities in 10 cities across the country.

The BOX is about men in solitary confinement, the guards who look over them, and the people on the outside who love them. The language of the play comes from interviews with incarcerated and formerly incarcerated people, and the action is based on the historic 2013 California Prisoner Hunger Strike.

In a larger sense, The BOX is about the shockwaves of mental, physical, spiritual, and emotional trauma sent through our society by the torturous practice of arbitrarily disciplining human beings by isolating them in cells not much bigger than a parking space.

Solitary confinement is a practice that the United Nations deems to be torture. On any given day in the United States, 80,000-100,000 human beings are in solitary confinement for up to 23 hours with sentences ranging from days to decades. In the U.S. we are familiar with the concept of mass incarceration. We know that it is a thing. But I wonder how many Americans are aware of what the long-term effects actually are on a society that imprisons more of its own citizens than any other country on Earth?

I had never driven across the country before this tour. Our tour bus departed from San Francisco on July 10 and drove to Austin, Texas; Fayetteville, Arkansas; St. Louis; Chicago; Detroit; Philadelphia; Baltimore; Washington, D.C.; Winston-Salem, North Carolina, and finally Atlanta, on September 1.

The thing that struck me the hardest about our country, the thing that weighs heaviest on my soul, is that in every city I visited, I met—without even trying—people affected by the prison system.

In the short periods of time I had to explore each city—shooting pool at a bar, eating at a restaurant, or walking down the street—I had a chance to meet and talk with people from all walks of life. All I had to do was tell someone why I was in town, and the conversation’s tone shifted. I would then get a story of incarceration or how the person was managing having a loved one on the inside. I was at the laundromat in one city. The attendant was an elderly man who told me he spent time in solitary in the late ‘60s back in Los Angeles. By the time I left most cities, I had inadvertently met four or five criminal justice system-impacted people. In Baltimore, I met nine.

In the “Land of the Free,” it is easy to meet people who have spent days, weeks, years, and decades without any freedom at all. Each time I was told someone’s story of incarceration, the amount of indignities piled on top of their initial incarceration was dizzying.

To me, this is the shame of our nation. It seems to me that a prison system should be designed to help people who have lost their way. But our system just seems to pile on misery. How can we expect to rehabilitate anyone in a place where they have to abandon their humanity and empathy in order to survive day to day? No one can get over trauma in a constant fight-or-flight state.

After each show we held an engagement circle with the audience to help the crowd release the energy created by the show. And we would invite people in the audience to share their own stories, feelings, or thoughts. We encouraged system-impacted folks to speak first. Their stories were harrowing.

But as I listened, it suddenly clicked with me that in our society we are all system-impacted. We all pay for mass incarceration with our tax dollars. And because of that innate connection to the system, if we are silent on the issue of how human beings are treated in our jails and prisons, we are even more complicit.

California’s legislature just passed a bill that would restrict solitary to no more than 15 days at a time, proving that change is possible. California's Gov. Gavin Newsom, a Democrat, vetoed the bill, a reminder that change is hard.

A lesson from the End of Isolation Tour is that change only occurs if we all speak out and act. One of our community partners in Atlanta, Pamela Winn of RestoreHER.US, put it this way: If you can only take one step toward justice, take that step. Because 5 million people each taking one step becomes 5 million steps toward justice.

On the End of Isolation Tour, I brought my skills as an actor to the restorative-justice table. It’s what I best have to offer in this movement. I loved the idea of playing a Mexican-American gang member who doesn’t have to use violence to accomplish his goal. Instead, Victor Santiago’s super power is love.

Through shared empathy, Victor learns to love his enemy. In so doing he creates a cross-racial alliance that brings together over 20,000 inmates in a hunger strike that forces the prison system to change for the better.

Imagine if we all offered our strengths to help make positive change. What powerful steps toward justice those would be.

Project

NewsArts

NewsArts: a Pulitzer Center initiative that explores the intersections between journalism and art...