This year has been a difficult one for journalism, rife with threats against freedoms of the press and information. In the face of these challenges, the Pulitzer Center has maintained its mission to support in-depth and solutions-based journalism that educates the global community. Our projects and our journalist grantees have shined a light on complicated issues that affect all of us, from climate change and war to forced migration and incarceration.

As we conclude 2018, the Pulitzer Center invites you to revisit and reflect on some of the year’s important issues through the images from our reporting that have most moved each of our staff members on personal and journalistic levels.

Scroll down to view our photo selections and to read the reasons why the Pulitzer Center team chose to highlight the images they did. And many thanks to the photographers—all Pulitzer Center grantees—for the work that they do.

Consider supporting more projects like these by giving to the Pulitzer Center. Give before December 31, 2018 and your gift will automatically be matched by #NewsMatch.

Climate Change

Marvin Kalb, Senior Adviser: Sometimes the fate of nations and the work of thousands comes down to one soldier on lonely assignment at the top of the world.

Here, in this photo from grantee Louie Palu's feature story in National Geographic, as the Arctic ice melts in dramatic proof of climate change, a new Cold War seems to be emerging. American troops stand guard in the cold, probably concerned that over the near horizon Russian forces have planted their flag.

Kem Knapp Sawyer, Contributing Editor: Lucky, a silverback gorilla at home in the forest of Rwanda’s National Volcanoes Park, makes me smile. Excitement, a sense of discovery, the warm feeling that comes from a connection to nature, a feeling of oneness—it’s all here. But there’s also a certain wisdom in Lucky’s eyes and a darkness to the image. Elham Shabahat, Pulitzer Center student fellow from Yale School of Forestry, reports that droughts have led increasing numbers of people to enter the national park in search of clean water, all the while exposing gorillas to human pathogens. The gorillas are moving higher up the mountain, away from their food source. Their fate and that of the farmers have become intertwined—the increased temperatures and water shortages a constant reminder that climate change is real.

Mark Schulte, Education Director: I grew up looking at George Steinmetz's sweeping images of our planet, his camera taking me to places I'd never been, with perspectives I couldn't have imagined. The aerial photography he pioneered has been democratized by drone camera technology, but Steinmetz did it first, when it was significantly more perilous. So it's an honor to have worked with him on "Losing Earth," an important story whose historical approach is made vivid and immediate by the images and videos he made. I chose this one in particular because penguins are adorable.

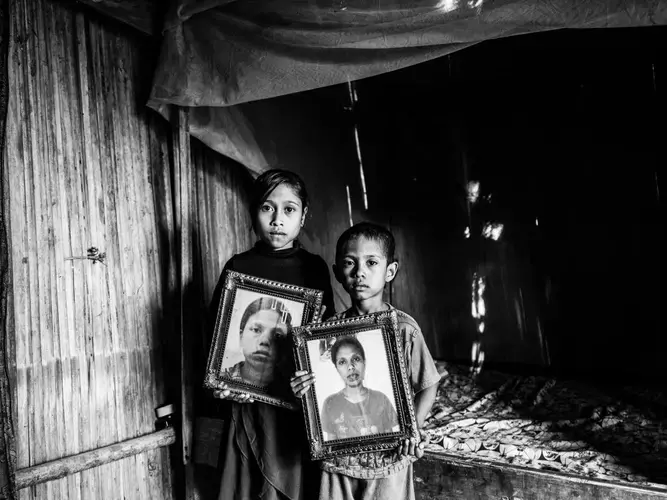

Ashley Zhang, Education Intern: Grantee Xyza Cruz Bacani's black-and-white photos are hauntingly beautiful. I was struck by the children's quiet sorrow and strength as they hold pictures of their late mother, Dolfina, a victim of human trafficking in Malaysia. She was one of the estimated 1.9 million Indonesians who moved there for work after droughts and fires caused by global warming made it impossible to farm in her rural hometown. When her body was returned, it had been mutilated by suspected organ traffickers. The effects of climate change are amplified for people living in poverty; those who try to escape often face the same fate as Dolfina. This photo puts a face to the victims of climate change and reminds us that global warming is a humanitarian crisis, and should be treated as such.

Global Goods, Local Costs

Jeff Barrus, Communications Director: High capacity batteries have changed our lives, making smart phones, laptops, electric cars, solar power, and more into viable mass market products. But like many technologies, these particular innovations come with a human and environmental price. Reporting for Fortune, grantees Vivienne Walt and Sebastian Meyer traveled to the Democratic Republic of Congo to see how cobalt—an essential ingredient in batteries—is mined. Far from the organized industrial concerns people picture when thinking of mineral extraction, the cobalt mine Meyer and Walt visited is little more than a vast open pit, lacking safety standards, or essential worker protections. This photo, depicting a young miner bundling cobalt during a day of hard labor, hammers home the fact that so many children and young people around the world work to extract the materials we need for our modern, high-tech luxury products. Tesla's electric vehicles may offer a "clean" alternative to fossil fuels in terms of carbon emissions, but are the materials that power them any less destructive than petroleum?

Global Health

Katherine Doyle, Associate Editor: Djooly Jeune is a teenager fighting Burkitt's lymphoma in Haiti, where he struggles to get the care he needs. He was diagnosed this year after several doctors incorrectly told his mother that he had a dental problem. Demand for pediatric cancer care is growing, but the scope of treatments available remains small. Patients in need of radiation and who can afford to travel will go to the Dominican Republic, or overseas. Grantee Jose Iglesias's photographs for this "Cancer in Haiti" series show the injustice of confronting a system so ill-equipped to handle the care of its population.

Karen Oliver, Office Manager: I like the light. I like her face. I like the memories this photograph brought me of living with my family in New Delhi a decade ago. But, please don't just look at this image and only marvel at a different culture. Please don't look at the other photos in grantee Larry Price's "Breathtaking" series and say "I'm glad it isn't like that where I live."

Shortly after we moved to India my eldest came home and reported that a middle school science fair project told her she was "smoking 20 cigarettes a day" just by walking around in the polluted city. If 12-year-olds can understand that we have a problem, the world should be acting. Let's find alternatives to coal and dung fires, but let's also establish and enforce emissions standards for industry worldwide. As this series with stories from India, China, Nigeria, Chile, and even the San Joaquin Valley in the United States illustrates, we have a global crisis. Let's focus on this complex challenge and solve it.

“Closing your eyes in front of the problem,” said Prashant Kumar, a professor and chair in air quality and health at the University of Surrey, “will not solve the problem.”

Incarceration

Hana Carey, Outreach Coordinator: I love anything that challenges my perception, and that’s why I love this particular image. With the sun peeking over the fence and her upward gaze, it feels hopeful. Without any context, I would never have guessed that this woman, Ms. F, was in prison. Grantee Shiho Fukada shows us an unexpected consequence of the aging population in Japan. With images like this, she also reminds us that every person’s story is unique and how important it is to question our own assumptions. Ms. F found prison to be a haven where she can find both care and companionship. Though she is not technically free, she has found a way protect herself from the societal challenges she faced outside of Iwakuni Women’s Prison.

Karena Phan, Intern: I found former inmate Chris Shurn inspiring. “Photography captures a moment in someone’s life, s— that we take for granted,” he said in my favorite quote from him in this story curated by grantee Brian L. Frank. “I didn’t think people would be interested in the s— I’m used to seeing every day.” And I thought that Frank’s portrait captured Shurn well. Even though I knew about the criminal justice reforms made in California, this story proves how there’s still work to be done. I think what struck me was not only Frank’s photography, but also Shurn’s and Riley's photography. Both are ex-inmates stuck in a vicious system, and even though they are enrolled in Project Rebound, a program that’s helping them get into college, they still fear that a minor infraction can send them back to jail.

Land and Property Rights

Tom Hundley, Senior Editor: For five decades, Susan Meiselas has been documenting some of the most important stories of our time. Her images from Central America, from the Middle East, from some of the quirkiest corners of the United States are timeless, universal, enduring—and speak to the photographer’s deep empathy with her subjects. I picked one that’s not exactly typical Meiselas—certainly not one of her most memorable or iconic images. A kitschy statue of Columbus extends a welcoming arm to a cruise ship, inviting tourists to enjoy the lush landscape and pristine beach in Honduras. The land is being appropriated from the Garifuna, an Afro-Caribbean people whose ancestors were brought to the Americas on slave ships. The irony works on so many levels.

Claire Seaton, Intern: In this photograph by Arko Datto, four girls wearing shalwar kameez uniforms lean over a physics lab experiment. The girls are all from indigenous communities in rural India, sent to a boarding school to receive formal education. One of them, Purnima (whose born name is Pukutti), is from the Dongria tribe, a group of people who have lived and farmed in the hills of eastern India for centuries. She’s one of many children pressured into an education often reminiscent of colonial, missionary-style boarding schools for indigenous children across North America, where settlers sought to extinguish indigenous language and culture through forced assimilation. Purnima loves math, and she is one of the best students in her class. My heart leaps to see girls around the world learning, but in this case it’s colored by attempts to separate indigenous children from their home culture. Undoubtedly, it’s necessary to educate youth about the world and empower them to make choices about their own paths in life. But it’s just as necessary to learn the knowledge systems indigenous groups have cultivated for generations. As indigenous rights movements gain further traction across the globe, I hope we work towards solutions that integrate cultures together on equal terms, rather than ethnocentric attempts at cultural assimilation.

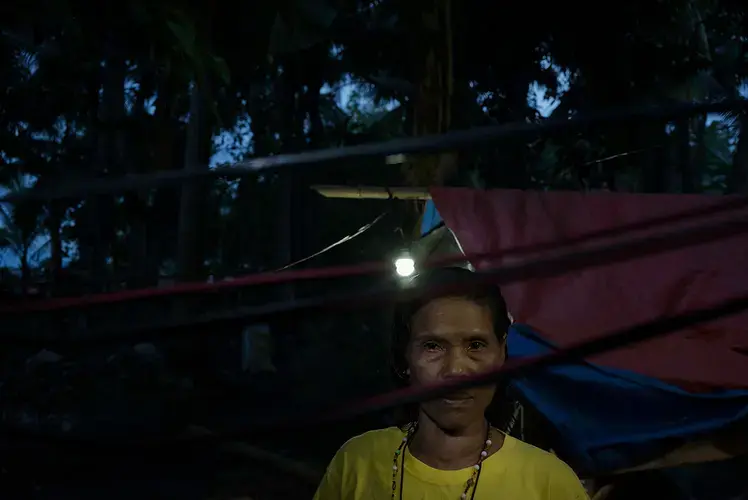

Lorraine A. Ustaris, Multimedia Producer: Electric cables obscure the subject’s face and impose a distance between her and viewers. Her placement in the photo reminds me she's at risk of disappearing from the frame. Still, her eyes stand ground and tell a tale that pierces across the divide. Magnum photographer Chien Chi Chang’s compositional choices drew me in, but I selected this image because of the name the photo's subject provided the journalists who interviewed her: Inday Bantay. “Inday” is a common Filipino word for girl, woman, or lady, frequently and almost exclusively used in place of a female’s real name. Loosely translated, Inday Bantay means "woman on guard." The reporting doesn't include this translation, but it's one I know because my family is from the Philippines.

Inday Bantay’s indigenous Filipino tribe, the T’boli-Dulangan Manobo, lives in a resource-rich region that has been coveted by the government and logging and mining companies that have encroached on their home for decades. Reporting for Pacific Standard, Chang and writer Max Ufberg document the struggle of the tribe in the aftermath of a December 2017 massacre, during which the armed forces of the Philippines killed 8 tribe members, including Inday Bantay’s son.

Like the history of most other colonized countries, the complex history of the Philippines is the centuries-long story of a contested land. It's a history that has created a deep and vast chasm between the identities and cultures of contemporary Filipinos and the indigenous Filipinos who first inhabited our islands. This reporting featured in Pacific Standard's issue, "Contested Lands," draws attention to the troubling perpetuation of this history in our midst. To me, in providing her nickname, Inday Bantay seems to characterize herself; she is “woman on guard” and calls us to view her as guardian of her tribal lands and her people’s fight against being forgotten.

On War and Peace

Jin Ding, Marketing Coordinator: Here we have a Tamil woman facing the wall in her house. This perspective conceals her identity, but makes her representative of the thousands of Tamils who lost family members in Sri Lanka's civil war. Though you can hear all the chaos in her life, at the same time, you hear silence. A decade afterwards, the war remains unheard of in most of the Western world, which has turned its back on the Tamils in this humanitarian crisis. Moises Saman's photo reminds us of the scars.

Ann Peters, University and Community Outreach Director: The universal image: a mother and child. Without a caption, without knowing where they are, we can imagine that this photo by Alex Potter from "Yemen: A Weary Nation" simply depicts a mother’s concern over her ill child. But there’s more: it sums up the weariness of a nation and its most vulnerable. For this mother of 12 in Yemen, she says she has had enough—and so she named her youngest just that, Kafaya. She’s exhausted from the conflict. And it’s only getting worse. While Pulitzer Center-supported journalists are out there, telling these stories to draw back the curtain on the humanitarian crisis, the Council on Foreign Relations says things are not getting better—Yemen is one of three countries given the awful designation of “worsening conflict status”—add Afghanistan and South Sudan to that cohort. Let’s not throw up our hands in despair. Instead, let’s figure out where we go from here to change that situation.

Jon Sawyer, Executive Director: The photography by grantee Nariman el-Mofty of the Associated Press strips away the empty verbiage of the politicians to show the ugly brutality of a dirty war that targets women and children first. In this image you don't see the face of any individual, just the fierce embrace by a mother of an emaciated child. You cannot look at this image without asking how and why. How did this come about? Why has the world not intervened to make it stop?

Population and Migration

Indira Lakshmanan, Executive Editor: A skeleton of a man whose hollow eyes hint at the indescribable horrors he’s witnessed clings piggyback to a younger man whose exhausted gaze is fixed blankly on the long road ahead. Trudging single-file to an unknown, stateless future, refugees from a once-peaceful farming village of Rohingya Muslims carry the only possessions they could salvage—plastic buckets, blankets, and some water. Survivors saw their children and neighbors gunned down, beheaded and mutilated by Myanmar security forces. Women were gang-raped and left for dead. Since August 2017, 700,000 Rohingya have been driven from the only homes they’ve known by state-sponsored “ethnic cleansing,” pushed into neighboring Bangladesh in the most rapid human exodus since the Rwandan genocide of 1994. Their testimony is the stuff of nightmares, and reminds me of horrors I heard recounted in Bosnia. The photos of Rohingya refugees by Patrick Brown and story by Jason Motlagh for Rolling Stone are unbearable, but we can’t look away. Perhaps the most important stories of 2018 are the desperate migration of people displaced from their homes and families by war, persecution, gang violence, climate change, and poverty from Asia, Africa and the Middle East to Latin America and the U.S.-Mexico border.

Race and Identity

Nathalie Applewhite, Managing Director: In April 2018, National Geographic devoted its entire April issue to race and how it defines, separates, and unites us. As culture editor for the magazine, Debra Adams Simons says in her introduction: “It’s the elephant in the room, permeating every aspect of our culture, neighborhoods, schools, businesses, politics, sports, arts, and relationships." Grantees Nina Robinson and Ruddy Roye captured images of daily life from historically black colleges and universities (HBCUs) in an essay written by Clint Smith. In this image, we see Maura Chanz Washington, a 2015 graduate of Spelman College (one of Pulitzer Center's Campus Consortium partners), celebrating Founders Day with friends. I love the spirit of freedom captured here. In a time when the issue of race is so often visually represented as one of conflict and protest, Nina presents another side—one of strength, success, ambition, and joy.

Hannah Berk, Education Coordinator: Grantee Melissa Bunni Elian's photo essay on the globalization of Afropunk cuts through a year of difficult news in order to celebrate identity and resilience. In powerful portraits of participants in the 2017 festival held in Johannesburg—the festival's debut on the African continent—she presents Afropunk as a movement, claiming space and creating community for the African diaspora. This image from a mosh pit at the festival captures the celebratory spirit of the story.

Elian begins with a big question: "Can art change the world?" Like Afropunk itself, her luminous photography celebrates resilience, imagines a radical future, and illustrates the possibilities of art for social change.

Religion and Power

Steve Sapienza, Senior Producer: This portrait from grantee Tomaso Clavarino’s "Prophets and Profits" project captures pastor Angel Obinim raising money from his congregation during a church service in Ghana. With Christianity and Islam on the rise in Africa, Clavarino’s reporting contributes to our understanding of how Christianity is spread there and also makes me wonder what the future holds for traditional African religions and non-believers on the continent.

Women, Children, and Crisis

Julia Kelmers, Development Manager: I fell in love with teacher Tuany Nascimento and her tiny students as soon as I saw them in Ballet and Bullets, a documentary film by grantees Frederick Bernas and Rayan Hindi. All of them, much younger than myself, look wisened and bright. They exist somewhere between being graceful and strong, looking brave yet feminine, and radiating confidence in an uncertain environment. Bernas and Hindi capture these big spirits in their photographs and film. They maintains the girls’ dimensionality as they try to navigate their violence afflicted favela. Since seeing these ballerinas, I haven’t been able to get them and their homemade tutus off my mind.

Fareed Mostoufi, Senior Education Manager: Grantee Marc Ellison’s project is an important reminder of how vulnerable children can be, and how easily communities can forget their responsibility to their youngest citizens. With a mix of documentary photography and original drawings in the style of graphic novels, Ellison’s project, “The Child Witches of Nollywood,” highlights the stories of young Nigerians who are accused of witchcraft by family members seeking answers for why they are facing seemingly insurmountable conflicts. These family members are bombarded with movies that reinforce their desires to blame witches for the poverty and illnesses they face, and the result of growing belief in witchcraft has led to thousands of children being left homeless in Nigeria’s Southwestern states.

Pulitzer Center’s education department endeavors to connect students worldwide with our reporting to examine how global issues connect to students’ local communities, and many students quickly connected Ellison’s story to the stories of the many young people in their communities who are left homeless or neglected as a result of societal norms and beliefs. I feel fortunate that I continue to see students around the world feeling compassion for the young people in Ellison’s work, and the young people facing discrimination in their communities. I love this image because it reminds me how resilient children can be, and how wonderful our world’s future will be when we allow young people to emerge from shadows and share their visions for a more compassionate world.