Why Teach this Book?

A Letter to Educators from the Author

Dear Teacher,

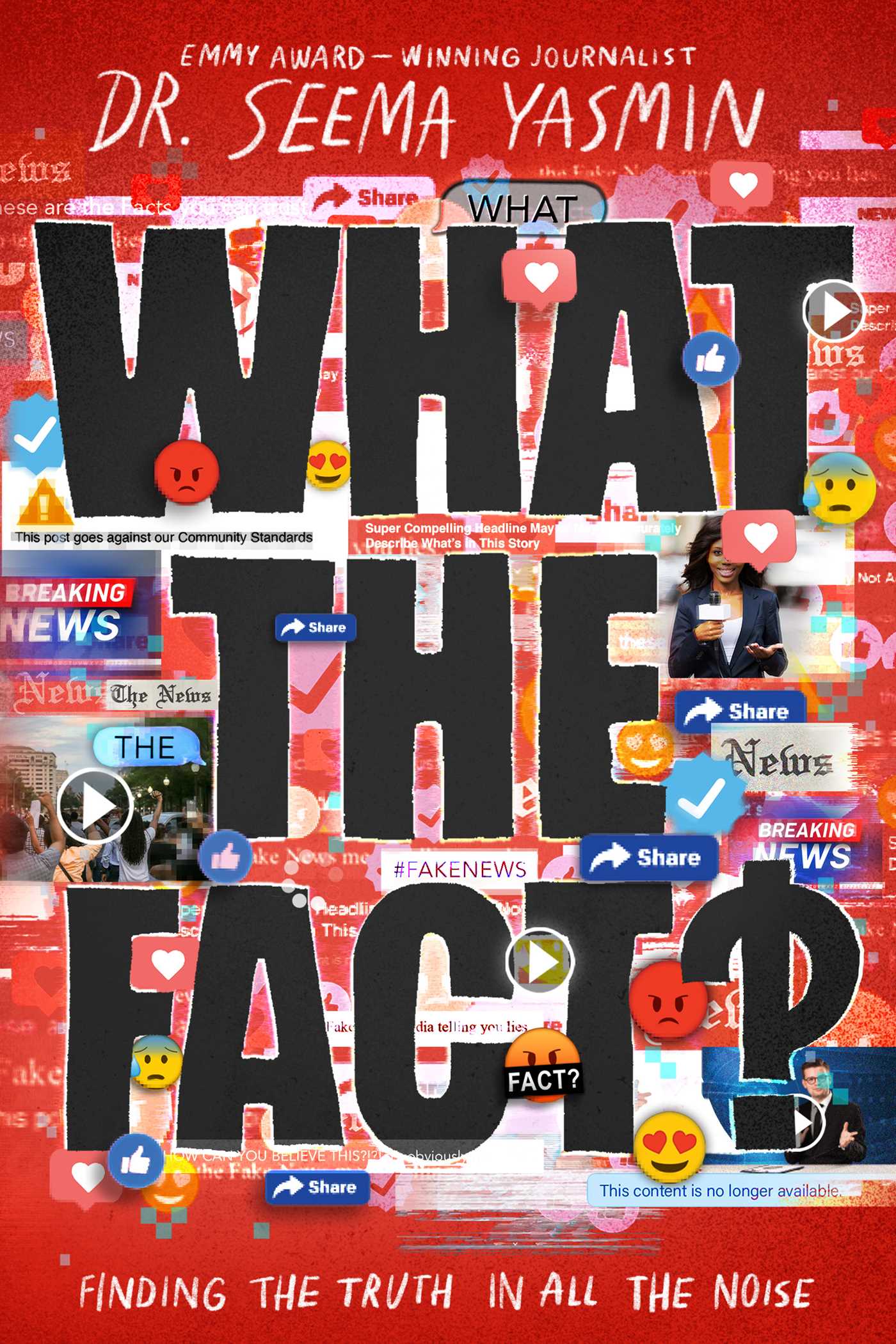

Thank you for bringing What the Fact?! into your classroom. I hope the book activates and energizes your teaching on critical thinking, media literacy, and digital literacy as they relate to civics, history, journalism, science, math, and English curricula. Thank you for teaching these essential topics!

This teaching guide contains chapter summaries and classroom activities that bring to life the concepts and anecdotes you’ll discover in What the Fact?! With exercises that put readers in the hot seat as social media bosses and newsroom editors, this guide includes activities that explore the impact of social media algorithms, investigate the way our biases impact our beliefs, and offers step-by-step instructions for effectively debunking myths. There are games that build mental resilience and protect against falling for false information so that we can “BS-proof” our brains.

I hope this guide proves fun and useful. In addition to this teaching guide, you can contact the Pulitzer Center education team to request a free virtual class visit from one of their journalists who can further explore these topics with your students. Please visit www.pulitzercenter.org/journalist-visits for more information.

Thank you for being our frontline defense against the viral spread of misinformation and disinformation. Myself and the team at Simon & Schuster and the Pulitzer Center hope that you enjoy teaching What the Fact?!

How We Hope This Guide Supports You

Welcome, educator. Because you have arrived at this teaching guide, you probably already know why we need an engaging, accessible guide to media literacy like What the Fact?!

Maybe you have students in your classroom who have fallen for some of the myriad hoaxes and conspiracies that aim to lure young people. Here, you’ll find tools to help them avoid future traps.

Maybe your students have heard so much about bias and misinformation in the media that they’ve become disillusioned with seeking out news altogether. Here, you’ll find a spark to re-engage them.

Maybe your students are asking you smart questions about how to sort fact from fiction, be a critical and open-minded thinker in an ever-expanding sea of information, and debunk the myths they encounter at home, online, and beyond. Here, you’ll find language, context, and evidence to support you in responding to their needs.

Studies show that young people feel smart, knowledgeable, and better equipped to take action in their communities when they engage with the news. But there are significant barriers to doing so. News often leaves students feeling sad, angry, or fearful, and they may feel that their communities and the issues they care about are under- or misrepresented in media.

Moreover, a growing body of research suggests that students have difficulty identifying false information, evaluating source bias and credibility, and distinguishing among news, opinion, and advertising online. For example, when asked to assess the credibility of a climate change website, fewer than four percent of high school students participating in a Stanford study went beyond surface level features like website domain and aesthetics to consider the organization’s major funding sources: in this case, the fossil fuel industry. Students aren’t alone. Navigating the constantly shifting landscape of news, social media, and information bombardment is a daily challenge for us all.

We hope this guide will support you in using What the Fact?! to answer your questions and those of your students, and to spark new lines of inquiry that ultimately result in classrooms full of curious and critical truth-seekers and -tellers. We also hope this guide will help you identify how the text fits into your learning goals, curriculum, and standards. There’s something here for everyone.

How can this book support me if I’m a…

- Language Arts or Journalism educator? What the Fact?! is a testament to the power of language and storytelling to shape our minds and our world. This book is on a mission to turn us all into critical thinkers and expert communicators. It makes text analysis and communication skills immediately relevant by offering practical tools for responsibly navigating the ideas students encounter every day in news media and online articles, social media posts, and conversations with the people in their lives.

In addition to supporting myriad Language Arts learning goals around text and multimedia analysis, WTF provides an illuminating look into journalism from Dr. Yasmin’s perspective as a long-time reporter. Journalism students will learn about the history of Western journalism and the evolution of its norms, the structure of newsrooms, and how editorial decisions get made.

While encouraging students to be critical, WTF discourages cynicism and overarching skepticism (such as the annoying and depressing advice: “Just don’t believe anything you see, hear, or read!”). Instead, this book challenges students not to shut down when faced with a complex landscape of bias and (mis)information, but to actively seek out truth and to maintain a curious and open mind. While engaging with this content, students can also analyze Dr. Yasmin’s writing to evaluate the purpose, structure, and tone of the book.

- Social Studies educator? By equipping students with strong media literacy and digital literacy skills, you are preparing them to act as empowered members of their communities and informed participants in democracy. Every tip and guide in this book (and there are many!) strengthens civic competence.

In addition to addressing the nature of modern-day misinformation, WTF is also deeply rooted in history. Dr. Yasmin shows how the spread of falsehoods has persisted in many forms over time, from outlandish myths in 17th century Europe to racist pseudoscience that was used to justify enslavement to information warfare and government propaganda deployed in the Cold War.

A fundamentally interdisciplinary text, WTF explores elements of psychology (how do we develop biases, and how do they influence our behavior?), economics (how do advertisers and consumer demands shape the production of news?), law (what is the relationship between the First Amendment and social media regulation?), and so much more. - STEM educator? A medical doctor and epidemiologist, Dr. Yasmin is always evidence-based in her approach to media literacy. Students can learn about science, math, and technology through the content of WTF, which details the brain science that makes us susceptible to falsehoods, how mathematics can be leveraged to misrepresent data, and how social media algorithms are engineered to exploit our brain’s dopamine reward pathways. At the same time, students can learn how to communicate scientific knowledge to a public audience by observing how Dr. Yasmin makes complex and often technical subject matter fun to read and easy to understand. WTF encourages students to be the best kind of scientists: those who constantly, enthusiastically question the world around them, and their own perceptions, biases, and beliefs.

What Do You Know, and How Do You Know It?

A lesson to introduce this book

Step 1. Choose an object, any object, in your classroom. Ask students individually to make a list of five pieces of information that they know about this object.

Next, ask students to review their list and assign a value representing how certain they are that each piece of information is true (1=not at all sure, 10=completely sure).

Invite students to share items from their lists aloud until you have a strong class list recorded on a whiteboard, poster, Google Doc, or other shared space.

Step 2. Go through the list one by one as a class and discuss:

- If you believe this to be true, where does that belief come from?

- If you do not believe this to be true, where does that belief come from?

- What are some factors that could cause someone’s beliefs about this to differ from your own?

- What would have to happen for you to raise your certainty about this belief to a 10? What would have to happen for you to lower your certainty to a 1?

Guide students in looking deeply at how they know what they know, and how others’ beliefs and perceptions could differ. For example, if they are certain that the object is a particular color because they can see it with their eyes, could someone’s belief differ if they were color blind? If they were to see the object in a different light? If their language had more or fewer words for colors?

Step 3. Repeat the activity, this time using a somewhat more controversial subject–preferably something you have discussed in your classroom recently. (For example: a law; a world leader or historical figure; a scientific innovation; etc.)

Step 4. After completing both exercises, discuss as a class:

- Did you find your certainty was stronger when listing information the first or second time? Why do you think that is?

- Did you learn anything new from the discussion, or change any of your previous beliefs?

Step 5. Introduce What the Fact?! to students by reading the “About the Book” and “About the Author” sections in this guide. While this book is about “separating fact from fiction,” doing so means we have to determine: what is a fact? Where do facts come from? And how do we know one when we see one? Reading this book will provide some answers, and a lot more questions.

Closing. Having read an overview of What the Fact?!, ask students to fill out the graphic organizer below as an exit ticket or as homework. Collect students’ responses. These can be used to structure future class warm-ups and discussions, and to identify sections of WTF that may be especially relevant to your students’ questions.

Chapter Guides

These guides offer summaries, key vocabulary, and suggested discussion questions for the introduction and five chapters of What the Fact?!

Introduction

| Summary | The introduction outlines the purpose of this book: not to tell us what to think, but to explain where (mis)information comes from, how it travels, and how our brains react to it–and what we can do to critically process and share information. |

| Media Literacy Vocabulary Note: WTF supplies definitions for most key terms in the text. |

Bias Myth Hoax Conspiracy Source Debunk Information ecosystem Disinformation Misinformation |

| Discussion Questions | 1. Do you consider yourself a freethinker? How has this introduction challenged, expanded, or reinforced your ideas related to freethinking? 2. Can you think of any times when you or someone close to you unknowingly shared false information? How might someone make this mistake? 3. What does Dr. Yasmin state as the purpose of this book? How do you think this book could be useful to you and to people you know? |

Chapter 1: Contagious Information

| Summary | Dr. Yasmin demonstrates how information can spread like a contagious virus. This chapter also makes a case for how using precise language can equip us to recognize and respond to misleading information, and introduces an expanded vocabulary for doing so. |

| Media Literacy Vocabulary Note: WTF supplies definitions for most key terms in the text. |

Viral spread of information Bots Trolls Fake news Misinformation Disinformation Malinformation Satire Misleading content Imposter content Manipulated content Fabricated content Logical fallacy Straw man argument Cherry picking Conspiracy theory |

| Discussion Questions | 1. Why is it important to consider the intent behind the construction and sharing of false or misleading information? 2. How can knowing about the key techniques used to spread lies help you spot false and misleading information? 3. Why is precise language important in recognizing and combating the spread of false or misleading information? |

Chapter 2: Bias, Beliefs, and Why We Fall for BS

| Summary | This chapter examines different types of bias, the social and biological factors underlying them, and how unexamined bias can lead to the spread of misinformation. It also delves into how storytelling interacts with the brain and communicates information effectively. |

| Media Literacy Vocabulary Note: WTF supplies definitions for most key terms in the text. |

Implicit bias / unconscious bias Heuristics Confirmation bias Assimilation bias Dunning-Kruger effect Polarization Inductive reasoning Deductive reasoning Skepticism Stereotypes |

| Discussion Questions | 1. What makes information compelling to you? Think about what kinds of media you like to engage with, who you trust, and why. 2. Dr. Yasmin writes that “presenting only the facts is not enough to shift a person’s perspective on the world.” Why is that? What else do you think is necessary? 3. How can strategic storytelling influence our beliefs and actions? 4. Why is it important to acknowledge our biases? 5. How are your beliefs connected to your sense of belonging and community? |

Chapter 3: News, Noise, and Nonsense

| Summary | Dr. Yasmin traces the history of the U.S. press to its roots in partisan pamphlets, the commercialized Penny Press, and the professionalization of journalism. Special attention is paid to the rise of objectivity as a central value in reporting, and how people who belong to groups long marginalized in the journalism industry have argued against the concept of neutral journalism, which can function to maintain the status quo. |

| Media Literacy Vocabulary Note: WTF supplies definitions for most key terms in the text. |

Propaganda Satire Penny Press Clickbait Partisan The First Amendment The Pony Express Telegraph Inverted pyramid structure Agenda setting Gatekeeping News judgment News aggregation Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) News desert News budget Framing Selective exposure Hallin’s spheres Editorial Op-ed Bothsidesism Movement journalism Media diet |

| Discussion Questions | 1. What is one thing you learned from this chapter about journalism in the past or present that you didn’t know before? 2. Should access to credible news be looked at as a public good or a commodity? What are the implications of each perspective? 3. What do you believe should be the relationship between objectivity and journalism? 4. Why is it important for reporters and leadership in the journalism industry to include people with diverse identities and experiences, both in their newsrooms and in their news stories? 5. What makes a news diet healthy? What are three questions you think are important to ask yourself about the news you consume? (Feel free to draw on Dr. Yasmin’s suggested questions, or come up with your own.) |

Chapter 4: Social Media

| Summary | This chapter explores the power of social media to (dis)connect and (mis)inform. It explains how the brain responds to social media, the way algorithms work, and how well-intentioned scrolling can lead to disturbing content and radicalization. |

| Media Literacy Vocabulary Note: WTF supplies definitions for most key terms in the text. |

Algorithm Dopamine Neuroplasticity Radicalization Extremism |

| Discussion Questions | 1. What are some strategies you can use to check whether information you see on social media is true? How often do you use these strategies? 2. Do you think that any content should be banned on social media? If so, what content–and who should get to decide? 3. What are some steps people can take to have control of their own social media experiences? |

Chapter 5: How to Debunk and Disagree

| Summary | This chapter offers tools for having productive conversations about misinformation. It discusses how to have disagreements that center close listening, avoid high conflict, and are more likely to lead to empathy and common ground. It also provides tips for how to respond when others initiate such conversations with us. |

| Media Literacy Vocabulary Note: WTF supplies definitions for most key terms in the text. |

Cognitive immunology Prebunking Debunking Looping Principle of charity Deep canvassing Groupthink |

| Discussion Questions | 1. When can conflict be good? What examples of good conflict have you seen or experienced? 2. Think about a time when you realized you were wrong about something, and changed your mind. How did it feel? Who or what caused you to update your beliefs, and how? 3. This chapter describes looping, and other deep listening techniques. What is the value of being listened to? What can people do to make you feel heard? Can you use these practices when listening to others? |

Extension Activities

After reading What the Fact?!, use these five extension activities to deepen students’ engagement with the text through hands-on activities and independent projects.

Activity 1. You’re in Charge: Agenda-setting and editorial judgment

Inform students that they have been put in charge of a news organization as editors, and it is their job to make the final call about what stories make it onto their website, pages, or airwaves. For this activity, students can work independently, or in small groups as editorial teams.

First, provide students with information about their news organization. (Where are they located? How often do they publish? Do they focus on local, national, and/or international news? Do they have a topical focus? etc.)

Second, provide students with four news events taking place that day. (Consider curating these events from multiple publications with different profiles. Be sure to include events that center the experiences and needs of different communities. For a free archive of underreported stories published by hundreds of local, national, and international news organizations, visit the Pulitzer Center website at www.pulitzercenter.org/stories.)

Students work to choose two out of the four news events that they will publish, and prepare to explain why, verbally or in writing. Questions students should be able to answer include:

- Which communities does their editorial judgment center, and which does it exclude?

- What does their editorial judgment say about the purpose and audience of their news organization?

Activity 2. What’s Your Angle? News framing and subjectivity in journalism

Dr. Yasmin defines framing as “decisions about which angle the story will be told from and whose voices it will feature” that “can change the entire story and the audience’s perception of the issues the story explores” (116). Framing can shape how audiences think about the people, places, and events news stories explore.

To give students hands-on experience with the power of framing, provide them with a news story, stripped of its headline. (You can choose a story related to topics you’ve recently covered in class, one from yesterday’s local newspaper, or from the Pulitzer Center’s archive of underreported stories at www.pulitzercenter.org/stories.)

Working independently or in small groups, ask students to read the story closely. After they finish reading, students should write down…

- A short summary of the main news event covered in this story, trying to stick to the most basic facts

- What they think the journalist wants the reader to think or feel about these events, and evidence from the story for their answer

Time permitting, have students swap summaries with at least two other students/groups, and compare and contrast. Did other students include different information in their summaries? Did they use different language that changes how the people, places, or events in the story might be perceived?

As a class, discuss: What do you think is the framing of this story? Consider the language used, the people quoted, the photos included, and more. (For more on classic types of news frames, see WTF chapter 3. Students can also discuss more generally the perspectives they see in action in the story.)

Finally, students work to generate 3-5 different headlines for the news story. Each headline should offer a different frame/interpretation. Collect different headlines in a centralized location such as a Google Doc, poster, or whiteboard, and conclude by discussing: which headline would students choose if they were the story editor, and why?

Activity 3. What Does the Data Say? Science, math, and misinformation

Introduce this activity by discussing as a class: Do you think science and mathematics are objective, or neutral? Why or why not?

Read the excerpt below aloud as a class (WTF chapter 2, page 81):

“Science is not neutral, and scientists are not unbiased robots conducting experiments in a vacuum away from the cruel realities of the world. Acknowledging scientists’ human biases helps us interpret their results with deeper understanding. And it helps us grapple with the problem of pessimistic meta-induction, the idea that because science has messed up in the past, it will mess up again. And not only science. Pessimistic meta-induction applies to economics, law, medicine, and politics. All these fields have murky pasts (and presents) replete with biases and mistakes.

“Diligent scientists think carefully about this. They swim around in uncertainty, semi-comfortable that the experiments they run and the data they produce inch us closer to some version of the truth—a truth that can be disproved at any time.”

Discuss as a class:

- How does this passage challenge, expand, or reinforce your ideas about objectivity in science and math?

- Can you think of any examples of how science or math have been used to mislead people? (Explore chapter 2 in full for more examples.)

Next, present students with a piece of data or a dataset pulled from a news story or academic paper. Consider using data related to a topic or scientific/mathematical model you have discussed in class. Here are some examples:

Independently or in small groups, students should study the data and come up with:

- At least three inferences they can make by looking at the data (if students explore raw data instead of descriptive statistics)

- Three different potential explanations for the data

- At least three questions they have in response to the data

After students develop inferences and questions, share an excerpt from the news article or academic paper with students that contextualizes the data. (If possible, present students with two authors’ explanations of the same data.) As a class, discuss:

- How do the author’s inferences and explanations compare with your own?

- Did the excerpt answer any of the questions you posed?

- Did the excerpt generate any new questions for you?

- What does your class’s ability to come up with differing inferences and explanations based on the same dataset say about neutrality in STEM? What do you think might account for these differences?

Here are some examples of data

- “Nearly 85% of the COVID-19 vaccine doses administered to date have gone to people in high-income and upper middle–income countries. The countries with the lowest gross domestic product per capita only have 0.3%.” (Source: “Rich Countries Cornered COVID-19 Vaccine Doses. Four Strategies to Right a ‘Scandalous Inequity’” by Jon Cohen and Kai Kupferschmidt for Science / Note: Article contains a graph that can be used in place of this text)

- “Nearly 50% of Richmond's population is Black, and the pre-pandemic eviction rate was just over 11%. Buchanan and Dickenson counties have nearly the same poverty rate as the city of Richmond, yet their eviction rates have been below 1%. Both counties' populations are also more than 95% white.” (Source: “In Richmond, VA, Eviction Burden Weighs Heavier on Black and Brown Residents” by Brian Palmer for PBS NewsHour)

- “About 230,000 women and girls are incarcerated [in the U.S.], an increase of more than 700% since 1980.” (Source: “No Choice but to Do It: How Women Are Criminalized for Surviving” by Justine van der Leun for The Appeal / Content notes: this story discusses sexual violence, domestic violence, and experiences of incarceration)

- “[The Indonesian Elephant Conservation Forum’s] unreleased 2019-2029 elephant conservation plan…reports that the population of Sumatran elephants now stands at an estimated 924-1,359 individuals — a drop of 52-62% over the 2007 figure.” (Source: “Saving Sumatran Elephants Starts with Counting Them. Indonesia Won’t Say How Many Are Left” by Dyna Rochmyaningsih for Mongabay)

Activity 4. Social Media Challenge: Fact-checking your newsfeed

Assign students a topic or allow them to choose a topic trending on social media, and challenge them to fact-check ten posts about this issue. (Ideally, students should fact-check posts they encounter organically. However, they can also use search tools on social platforms to find past posts.) Offer this guide to students:

Step 1. Create a spreadsheet or another document that contains the post link, the post author, and a list of factual claims made in the post. (Note: You do not need to include opinions in your list of claims, as these are subjective. An opinion may be formed on the basis of true information or misinformation, but it is not true information or misinformation itself.)

Step 2. Research the post authors. (Is the author a journalist? Doctor? Activist? Member of the public? Are they affiliated with any organizations? What comes up when you search for their name online?) Note who the author is, and any important affiliations in your document.

Step 3. Research each factual claim made in the posts. These guiding questions may help:

- Is the information attributed to any source? If so, are they an appropriate, knowledgeable source?

- Do news stories, organizations’ websites, or peer-reviewed articles support the factual claims you identified? Can you find any sources that contradict the claims?

- Record in your document: Is the claim true, false, or unverified (i.e. you could not find enough information to make a judgment)?

Step 4. Write a one-two page reflection on what you learned from analyzing social media posts on this topic for a day.

Activity 5. Be a Media Literacy Superspreader

Students will come away from WTF with a wealth of tips on media literacy, digital literacy, and communication. Not only will they be equipped with the tools to be more critical of sources and arguments, more open to questioning their own assumptions, and more effective in sharing their ideas with others, but they will also understand how these skills can improve their lives and their communities. Dr. Yasmin explains that misinformation has a nasty tendency to spread like a virus. But students can build a healthier news ecosystem by sharing their new and strengthened knowledge and mental immunity against lies with others.

Charge students with identifying their top 5-10 tips from WTF, and finding an engaging and accessible way of sharing them with others–keeping their intended audience and the best way to reach them in mind. Here are some ideas:

1. Create a series of infographics combining the text of the tips with appealing images using a free design software such as Canva. Post the images as a carousel on Instagram, a thread on Twitter, or on another class/school social media account.

2. Collaborate with your classmates to put together a presentation highlighting several media literacy tips, and offer to present it to other classes at your school. Be sure to include interactive elements so that you can engage your peers’ preexisting knowledge and give them some hands-on practice with the tips you share.

3. In chapter 2, Dr. Yasmin explains how strategic storytelling can help people remember and internalize information better than a list of facts. Choose one tip from your list, and write a short story that illustrates its importance. You can write a fictionalized story (you might use the story about a mother and her daughter’s disagreement about the causes of gun violence in WTF chapter 5 as a model), or a nonfiction story (you might use the story about Onesimus and the invention of the smallpox vaccine, from the same chapter, as a model).

Bonus Activity: Invite a Journalist to Speak with Your Class

Extend your students’ learning by giving them the opportunity to hear directly from a journalist about how they handle questions of bias, news judgment, representation, objectivity, and more. Students can get their questions about the reporting process and navigating the news answered, while learning about the systemic issues journalists cover, as well as careers in the industry.

The Pulitzer Center offers free virtual visits with journalists to classrooms, afterschool programs, and education programs in jails, prisons, and juvenile detention facilities. Visit www.pulitzercenter.org/journalist-visits to learn more and request a guest speaker.

Key Takeaways: Ten Media Literacy Lessons from What the Fact?!

We hope this teaching guide has sparked ideas for how What the Fact?! can support your students’ needs, and your curricular standards. This book is chock-full of step-by-step guides to bolstering your critical thinking, media literacy, and digital literacy skills. To point you toward some of the key strategies laid out in this book and where to find them, here are ten media literacy tips from WTF. Consider asking your students to make their own list of media literacy tips they want to use and share while they read!

1. Use precise language.

“Specific terms are not only going to make us sound much smarter but they can help us better understand who created the false information, who was spreading it, and why.”

Terms like fake news obscure how misinformation really spreads, and who benefits. Recognizing the full spectrum of false and misleading information and determining which you’re dealing with can help you avoid falling for falsehoods that take less obvious forms and better understand how to stop their spread. For more advice on using precise language, see chapter 1.

2. Recognize common strategies used to spread misinformation.

“Digging into five key techniques used to make us believe lies helps us have those essential Aha! moments when we spot these techniques in action.”

Scholars have developed a classification system for techniques of science denial and the spread of disinformation called the FLICC taxonomy. FLICC stands for fake experts, logical fallacies, impossible expectations, cherry picking, and conspiracy theories. Learning about these techniques is the first step to debunking disinformation. For more advice on using the FLICC taxonomy, see chapter 2.

3. Acknowledge your bias.

“Understanding and acknowledging our biases can protect us from falling into traps of simplistic thinking.”

The work of identifying bias in the information we encounter starts with interrogating our own biases. Everyone has biases, and they can even serve useful purposes! However, unacknowledged biases can make us much more susceptible to misinformation, and lead to harmful results for ourselves and others. Be mindful of questioning information that confirms your beliefs as often as you question information that surprises you. For more advice on acknowledging bias, see chapter 2.

4. Do your own fact-checking.

“Every chunk of data has its own origin story.”

When you learn something new, ask where that information came from, and try to trace it as far back as you can. Developing a fact-checking habit will help you identify where your knowledge and beliefs are coming from, and can strengthen your confidence in your ability to sort fact from fiction. For more advice on fact-checking, see chapter 3.

5. Build an intentional news diet.

“Designing your own media diet gives you nourishing doses of information and entertainment and puts a lid on distractions so that you’re not as tempted to tap every time your phone pings or an alert pops up on some screen somewhere. It also means your worldview is challenged, because you are designing a diet that exposes you to different perspectives, and this can gently guide you out of your comfort zone.”

Consider what you want to get out of the news, and how you can do that. Lean into sources you trust, while also seeking out other voices to avoid an echo chamber. For more advice on healthy news consumption, see chapter 3.

6. Pay attention to who is telling the stories in your news diet.

“We all experience the world a certain way, are treated in different ways, and have varied backgrounds and life experiences, and if many different lived experiences were represented in the rooms where news decisions are made, journalism would better reflect the lives of the people who consume it.”

The journalism industry, and especially its leaders, are disproportionately white, cisgender, heterosexual, male, and able-bodied. Journalists’ identities and experiences shape which stories get told, and how. Seek out a diversity of storytellers to get a more well-rounded perspective. For more information on diversity and representation in journalism, see chapter 3.

7. Pull back the curtain on social media.

“[An] algorithm might run on a machine, but it was programmed by people who coded it to decide how to order content by the likelihood that you’ll enjoy and engage with it and stay on the platform for hours.”

Be mindful of how social media algorithms work, who designs them, how they profit, and how your mental health, privacy, and community are affected as a result. Major tech companies like to keep their practices and algorithmic details secret, but remembering that there are human beings and companies with their own set of interests curating your online experience can lead you to ask questions about the content that appears before you, and what perspectives might be missing. For more advice on navigating social media platforms, see chapter 4.

8. Take control of your social media experience.

“Social media has firmly planted its feet in our lives. It’s not going anywhere, and it offers amazing connections and information, but it’s important that you control its effects on your time, mood, and health.”

Pay attention to how much time you spend on different social media platforms, and how they make you feel. Make a plan to budget your time on social media based on your observations, and consider exploring platforms beyond the biggest, most profit-hungry ones. For more advice on controlling your social media experience, see chapter 4.

9. Practice active listening techniques.

“Over time, broad questions and deep listening can help soften tension and help people understand that they are not under attack.”

If you want to debunk misinformation or engage with a person who disagrees with you about a controversial issue, listening is one of the most powerful things you can do. It gives you a better chance of understanding where they’re coming from, encourages them to identify inconsistencies in their own thinking, and preserves your relationship in the face of conflict. For more advice on having healthy disagreements and debunking misinformation in conversation, see chapter 5.

10. Remember that you are the solution.

In the face of the many forms of false information and bias swirling around in the world and in our brains, it can be tempting to tune out and become a total skeptic. With so many pitfalls laying in wait, why venture forth into the sea of information? But keep in mind that good information is out there for trained truth-seekers! In fact, researchers estimate that only 0.15 percent of the news people in the U.S. consume is actually fake (see chapter 3). Armed with your critical thinking skills and an open mind, you will be able to make better decisions, understand other people more deeply, and engage in your community more effectively. Every time you use and share these skills, you are combating falsehoods and stereotypes in your online and IRL communities, and creating a healthier information ecosystem for us all.