New forms of PrEP to prevent HIV, like injectable CAB-LA, are coming. Public health officials hope they’ll help South Africa’s young women, one of the most impacted groups in the world, avoid the virus.

UMLAZI, SOUTH AFRICA—In South Africa’s Umlazi township, HIV is a part of life, even for those who don’t have it.

Twenty-two-year-old Pamella Jili has seen its impact up close. She grew up in the township, a hot spot in the worst-hit province in South Africa, where more people live with HIV than anywhere else in the world. She has watched others struggle with the virus. When dating, she has always worried about her partner’s status.

Despite living in the area experts have called the epicenter of the modern HIV epidemic, where two in three women will contract HIV by the age of 23, Jili has trouble taking a daily medication that nearly guarantees that she won’t contract it. Daily pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) pills prevent HIV from replicating in the body, halting new cases when used correctly. And yet, prevention with this pill is easier said than done.

“The problem is the pills,” Jili said. “People ask, ‘You’re so small, why are you taking pills?’ and they think they’re for HIV. We’re not even sick and we’re still taking pills.”

Swallowing them makes her nauseous. Beyond that, Jili says cultural norms and stigma leave her feeling ashamed to take them.

She’s not alone: Of 600 Umlazi women prescribed daily pre-exposure prophylaxis pills—known as PrEP—in 2018, just 18 were still taking them five months later.

Jili wishes she could take PrEP as a shot that would last for a year, or at least several months. That way, she wouldn’t have to think about it every day. She’s used to injections—it’s how she takes birth control, like most South African women who use contraceptives.

Soon, she might be able to do just that.

Promising new forms of PrEP are coming that would offer protection for months on end, empowering people like Jili to decide what’s right for them. An injectable PrEP called long-acting cabotegravir (CAB-LA) now exists, touting the most successful prevention outcomes ever seen in trials. And it could be coming soon: South Africa is expected to “make a regulatory decision regarding CAB-LA within the next few days,” health authorities told South African health publication Bhekisisa yesterday. If approved and priced affordably, the health department could start a large-scale rollout by August. Other delivery methods like vaginal rings, implants, and long-acting pills are in the works, too.

Although there will be battles to make these new medications accessible, they might stand a chance to break the cycle of transmission.

As the city wakes up on a hot summer morning in February at Umlazi’s Mega City shopping mall, Jili and a class of other young women ages 18 to 23 settle into a computer lab, ready to practice their technical skills. Later, they’ll discuss their experiences with HIV prevention.

They’re part of the Females Rising through Education, Support and Health (FRESH) program, an initiative run by Harvard, the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, and Massachusetts General Hospital’s Ragon Institute. FRESH aims to empower participants with nine months of career training and health education while performing clinical research.

The participants are all HIV-negative but sexually active locals who aren’t employed or attending school. They’re also poor: a substantial risk factor for HIV. Some have children at home.

Each is given PrEP, but most won’t take it long-term.

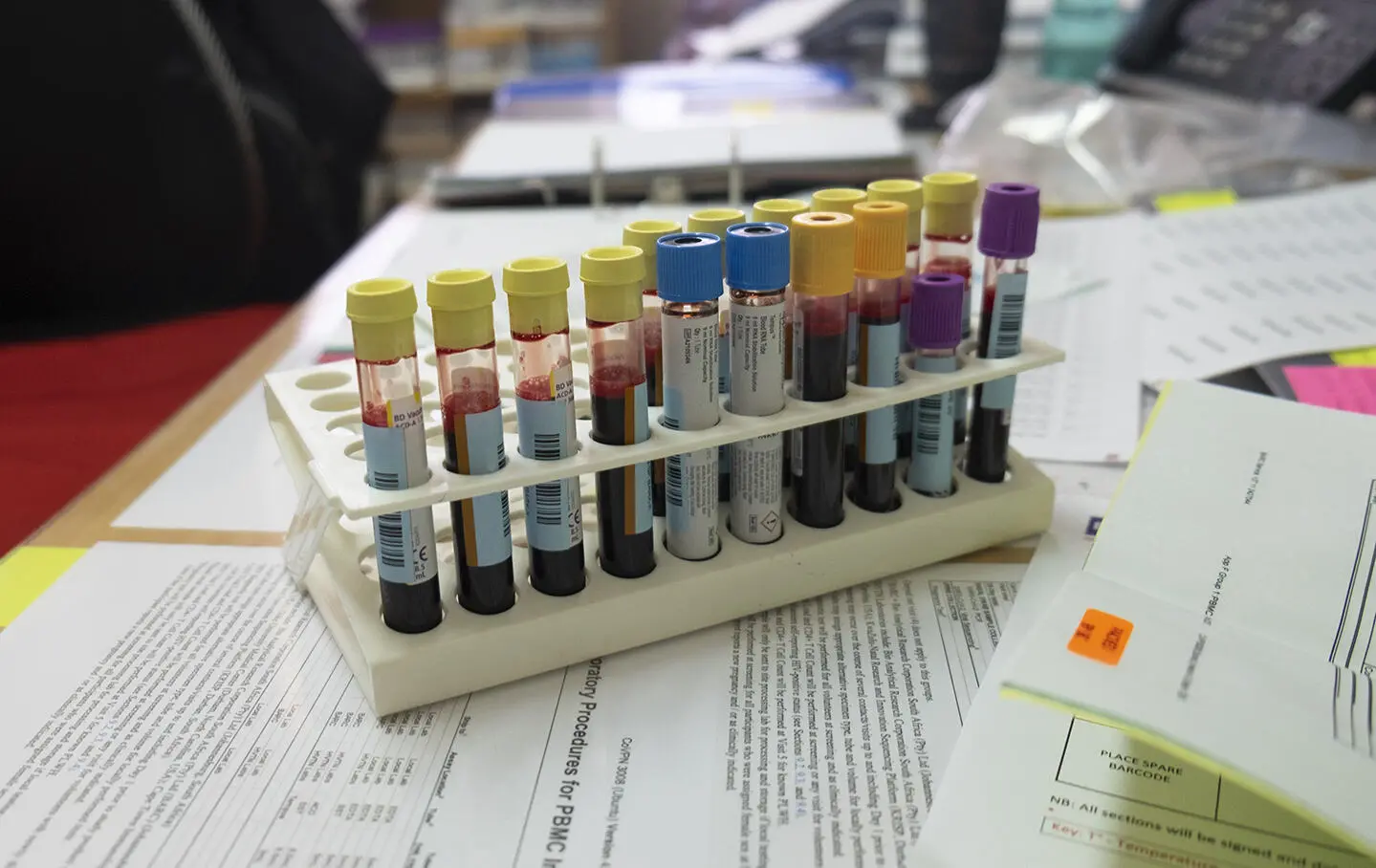

Twice weekly before class, nurses will test students for HIV with a finger prick, aiming to catch new cases within the first few days of transmission. This allows clinicians to quickly provide treatment while learning more about the earliest stages of HIV, which might hold clues to developing vaccines and medications.

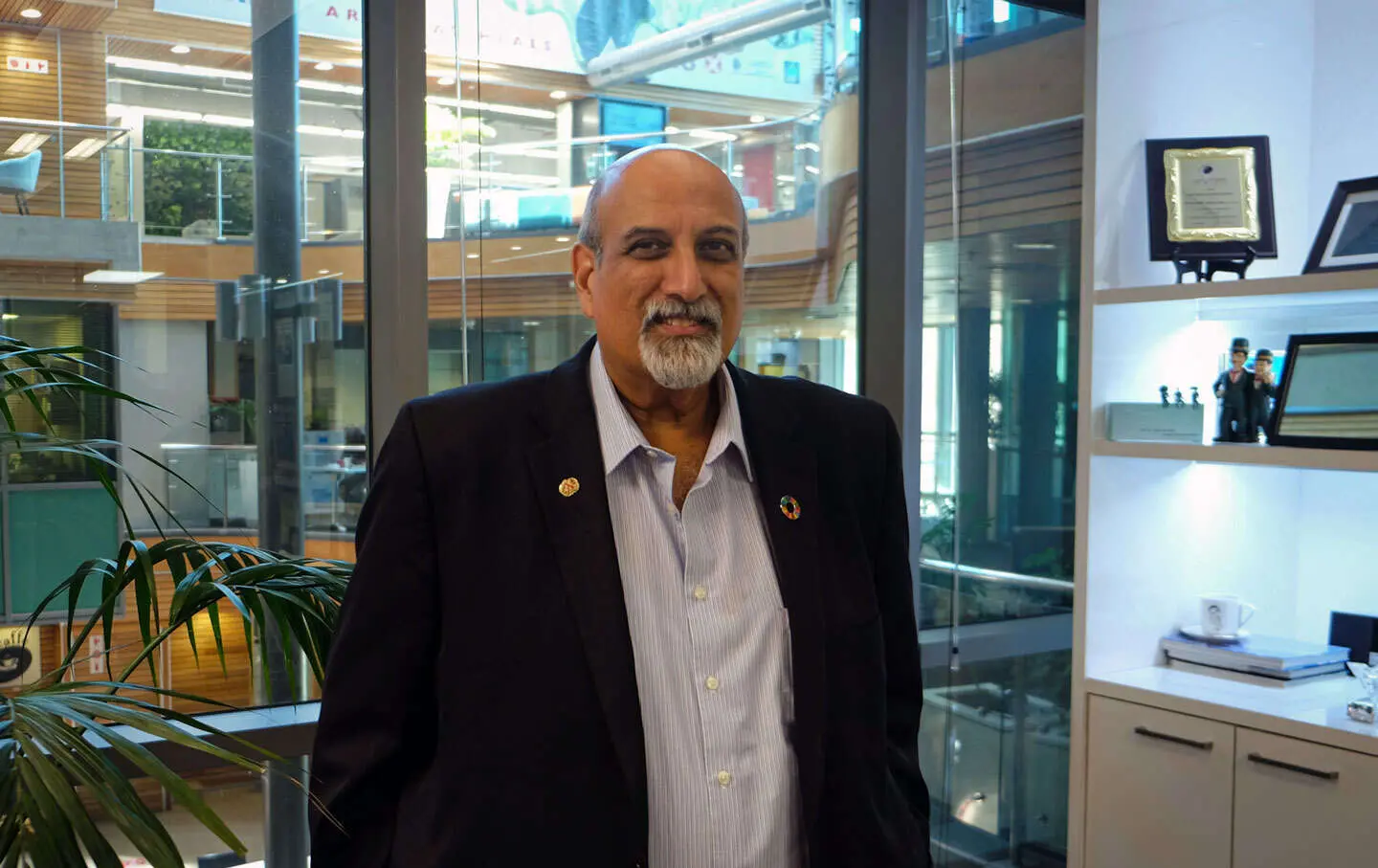

“We wanted to recruit young women at high risk of HIV acquisition, but at the same time do an intervention that benefits them in terms of preventing new HIV infection and changing the socioeconomic factors that make them so vulnerable,” said Dr. Thumbi Ndung’u, a deputy director at Africa Health Research Institute (AHRI).

Job opportunities in the region are sparse. South Africa’s youth unemployment rate soared to 67 percent earlier this year. Still, FRESH participants remain optimistic: Some want to be teachers, lawyers, and advocates. Jili dreams of becoming a flight attendant for Emirates in Dubai.

Many have loved ones dealing with HIV. Though modern medicine can keep people healthy, they still witness hardships. Worries about the virus permeate their personal lives too.

“If you’re finding a boyfriend, your first concern is his status, even if you’re scared to ask,” said Jili. “Nowadays, our boyfriends don’t want to use condoms. At the same time, you’re scared to ask his status.”

“And boys don’t want to get a test,” she adds. “They’ll tell you to do it, and if you’re negative, that means he’s negative.”

South Africa’s tumultuous fight with HIV

While South Africa is making headway on prevention and treatment, its decades-long struggle with the virus persists. Over 7 million South Africans live with HIV, or almost 1 in 5 adults nationwide, according to UNAIDS. Poor and Black communities face the worst burden.

The country got a late start in stopping HIV.

In the 1990s and early 2000s, as antiretroviral medications became available elsewhere, South Africa’s leadership rejected them based on both costs and conspiracy theories. At the 2000 International AIDS Conference, President Thabo Mbeki sparked uproar when he denied that HIV caused AIDS.

“I left very angry,” said activist Patrick Mdletshe of the conference. Mdletshe now heads community organizing at CAPRISA, an AIDS research powerhouse. “Sitting there listening made me feel so awful because I saw my friends dying of HIV from a very young age. It would not take a scientist to tell that this person’s dying of HIV, since it would make you so skinny and sick. HIV has its own way of embarrassing you—the world would see you dying.”

At that time, Mdletshe heard from global activists about the wonders of antiretrovirals—people weren’t dying anymore! But South Africa did not have them.

Finally, antiretrovirals became widely available in South Africa in 2004, enabling people to live healthfully despite an HIV diagnosis. But the lost time caused immeasurable suffering. In 2008, Harvard researchers estimated that Mbeki’s inaction led to 365,000 unnecessary deaths.

Since then, South Africa has made notable progress on treatment. Two in three residents living with HIV had suppressed the virus as of 2021, according to UNAIDS, meaning they could no longer transmit it to partners.

Oral PrEP entered the picture in 2016, marking the drug’s debut in Africa. The government soft-launched it in certain at-risk groups for free—sex workers, gay, and bisexual men, transgender women, and people who inject drugs. In 2018, young women meeting criteria qualified. Others can receive it, too, but must pay $17 monthly, which is expensive for lower-income South Africans.

Transmission is decreasing for everyone but young women

With medical advances, South Africa has seen a vast improvement in transmission rates. Young women have not benefited equally from this progress, however. New cases are steadily declining for all groups except them. South African women aged 20 to 24 were three times as likely to be living with HIV than their male peers, according to a 2017 study.

The primary driver is inequality.

In the wake of apartheid, South Africa has the highest income inequality in the world, as measured by the Gini index. Limited schooling and job opportunities, along with gender-based violence and uneven relationship dynamics, can leave women vulnerable.

Experts say that biological factors intensify disparities. Inflammation in the vagina’s mucosa tissue can render it more susceptible to HIV than the penis. Scientists suspect the prominent vaginal microbiomes in sub-Saharan Africa are even more prone to inflammation, which facilitates transmission.

Many experts say that a tendency to date older men can also put women in a more vulnerable spot than their male counterparts. Age gaps fuel what epidemiologist Dr. Salim Abdool Karim calls the “cycle of HIV transmission.”

“The cycle is where men in their late 20s and early 30s are having sex with women in their 30s, who have a very high prevalence of HIV—up to 70 percent in some communities here,” said Salim at CAPRISA’s Durban headquarters. “They don’t even know they’re infected.

“Then these men, about 40 percent of them have a liaison with a teenage girl. They pass the virus on, and that girl gets infected. She will then grow up and spread it to another man who may now infect another teenage girl who will grow.

“And that’s how the cycle continues.”

Salim first described the cycle in 1989, alongside his wife, Quarraisha, also a renowned epidemiologist. The couple have dedicated their lives to researching HIV after studying public health in New York at the height of its AIDS crisis and foreseeing the damage it would cause back home.

In 2016, they revisited the cycle with a genomic analysis linking 1,500 individuals living with HIV. The study found that young women were disproportionately acquiring HIV, from men an average of eight years older.

Researchers clarify this phenomenon isn’t uniquely South African, nor does it describe every relationship. In many cultural contexts, young women date older. The difference in South Africa is HIV’s omnipresence.

Some age-gap relationships come with an element of exchange. Twenty percent of women reported having transactional sex, said Dr. Maryam Shahmanesh, director of clinical science at AHRI. That doesn’t include entanglements where the lines of transaction are blurred.

Many young women in Umlazi recount being approached by men offering money for relationships or sex. These men are referred to as “blessers”—a local term for sugar daddies. When discussing the HIV epidemic among young women, plenty blame the blessers.

“Even here in the mall, we can find them. If I look pretty, as I am right now,” Jili said, fluttering her eyelashes, “five men or more will approach me asking for my number saying I’m beautiful. They’ll say that they can offer me whatever I want, that they can take care of me, that they can even give me money now.”

“Everything is about money,” Jili’s peer Amanda Khumalo added. “Even the water we are drinking, it costs money, so they’re taking advantage of young girls.”

Some believe the blesser narrative is overstated.

It envisions much older men with very young women, said Shahmanesh, but the men tend to be only “slightly older, in their mid-to-late-20s.” They’re not magnates, but rather younger men with a taxi or small shop.

“My worry is that lots of young women don’t identify as the young woman in those stories,” she adds. “They think, ‘My partner is only 25 and he’s local, he’s not a creepy old man,’ so they don’t see themselves at risk.”

Adoption of daily PrEP pills remains extremely low

Of one FRESH cohort prescribed oral PrEP, just 3 percent took it for longer than a few months.

In a survey, the class blamed side effects like nausea and the idea of taking pills every day. In their region, young people don’t often take pills unless they’re sick or keeping HIV at bay.

Then there’s stigma. Almost half of respondents feared their PrEP would be mistaken for antiretrovirals, leading people to hide their PrEP, lest family, friends or partners mistake the pill bottles for HIV treatment. Some even complained that the rattling of the bottles could be a giveaway.

“If someone comes over and sees them in your house, they don’t ask,” said Khumalo, who proudly takes PrEP daily, said with an exhausted laugh. “They just start the rumor that you’re positive.”

A “prevention revolution” is underway

Improvements are coming.

Scientists are evaluating new ways to expand the arsenal of prevention. Shots, long-lasting pills, vaginal rings, implants, and even doses of preventive antibodies might trickle into the market in the coming years.

“It’s being described as the prevention revolution,” said Dr. Linda-Gail Bekker, director of the Desmond Tutu HIV Centre in Cape Town and former president of the International AIDS Society.

An injectable form of PrEP called long-acting cabotegravir (CAB-LA) is especially promising, offering even greater protection in practice than daily pills. The shot, given every two months, removes the onus of taking pills daily and allows for discretion. It’s been introduced in the U.S. and gained approval in neighboring Zimbabwe, but awaits the greenlight in South Africa.

But a decision is imminent: South African officials told health publication Bhekisisa yesterday that they expect to reach a verdict within days. If pricing allows, the health department said they could introduce it into clinics nationwide by next summer.

A 2020 study demonstrated its effectiveness. When over 3,000 at-risk women received PrEP as either an injection or a daily pill, injections offered superior coverage. While 1.8 percent taking pills contracted HIV, just 0.2 percent on shots did—among the best results of any PrEP trial ever.

For those who want something else, a silicone ring inserted into the vagina that dispenses medication for one month gained approval in South Africa in March.

Daily pills will remain a key prevention tool, but other options will enable people to choose methods that best fit their needs. Advocates anticipate injectable PrEP and the ring will better suit the lives of young women.

A 2022 study predicted that with high levels of access and affordable pricing, CAB-LA could avert 52,000 new cases of HIV each year in South Africa, preventing 21,500 deaths from AIDS, over twice as many as they predicted with high levels of oral PrEP alone.

The battle ahead

But financial and logistical hurdles stand in the way of utilizing CAB-LA to its full potential.

“We’re appalled at how long it took to get oral PrEP,” said Bekker. “The whole advocacy community is anxious that this doesn’t happen again.”

If approved in South Africa, costs will determine whether the “juice is worth the squeeze,” as Bekker puts it. If priced affordably, the health department could begin introducing it nationally by next summer.

But advocates fear prices will not be low enough to benefit the poorer nations who stand to benefit the most from using CAB-LA. Though ViiV Healthcare, the drug’s manufacturer, has announced licensing agreements allowing generic manufacturing and reduced rates that assure costs won’t mirror American prices of $3,700 per dose, the drugmaker has not yet announced pricing.

To be cost effective for the public health system, recent modeling in medical journal The Lancet HIV has shown that prices can only be slightly higher than that of PrEP pills, between $9.03 and $14.47 per injection.

Another obstacle will be implementing CAB-LA: It requires a health care professional administer to administer it, which could prove challenging in rural and under-resourced areas. Providers will need to determine how it will fit into the system.

Some question if PrEP can break the cycle at all. Dr. Salim Abdool Karim is unsure.

“For impact with PrEP, you’ve got to get hundreds of thousands of young girls to take it,” Karim said. “Anything short of that is a puddle, and what we want is a tsunami to come through and protect these girls.”

But many remain hopeful about the choices coming.

Nombeko Mpongo, community liaising officer at the Desmond Tutu HIV Centre in Cape Town’s Philippi Township, has seen firsthand how a younger generation of women is responding to PrEP. She facilitated a clinical trial where young women tried both PrEP pills and vaginal rings for a year before selecting their preference. Two-thirds chose the ring.

Trained as a counselor, Mpongo gets to know the women as part of her work. She often hears young people expressing worries about the future, burdened by the economic situation and the nature of relationships.

To two young women who feared HIV would not improve in their generation, she offered this guidance: “The information that you are getting now, we were never informed about. When I was your age, I didn’t know any of these things. We had to suffer on our own.”

“I’ve been HIV-positive now for 24 years and I’m alive,” Mpongo said. “So there is hope, and there is going to be hope.”