Before 2020, Youngwha Sung had never been particularly interested in activism.

A busy mother of three, she had plenty of other priorities to occupy her time. She skimmed the news and voted when she could, but politics seemed a distant world from her quiet Pennsylvania suburb. She had always been proud of her heritage as a second-generation Korean American, but never saw any reason it might necessitate advocacy in any way.

Amidst mounting headlines of “anti-Asian violence” throughout the last three years, that feeling began to change.

As a nonprofit journalism organization, we depend on your support to fund more than 170 reporting projects every year on critical global and local issues. Donate any amount today to become a Pulitzer Center Champion and receive exclusive benefits!

“The more I saw the stories about what was happening [to Asian Americans], the more scared I felt,” Sung said. “COVID changed a lot of things. I thought about my kids, my family. I didn’t know how, but I want[ed] to do something.”

Sung’s path to activism is a common one these days for many Asian American Pacific Islander (AAPI) citizens across the country. Record voter turnout gains in the 2018 and 2020 midterms, combined with a national spotlight on anti-Asian violence, have brought about a critical period of AAPI political awareness and progress.

The challenge of maintaining this momentum loomed large over the 2022 midterms, but groups like the Asian American Power Network (AAPN) have stepped up to the plate. Their most recent launch of a $10 million grassroots engagement campaign will provide eager volunteers like Sung with the resources to continue expanding civic outreach to AAPI voters in their communities.

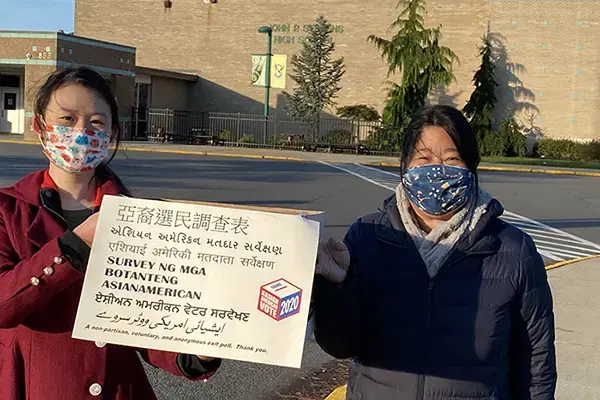

Network members canvassed all over the country, with concentrated efforts in battleground states like Virginia, Nevada, Georgia, and Michigan by network members. In Pennsylvania alone, AAPN-sponsored organizations were able to knock on over 140,000 doors and conduct voter outreach in 15 different languages ahead of the midterm election, according to the Asian Pacific Islander Political Alliance.

“I’ve been able to volunteer [with] phone calls in Korean and English, to talk to people about voting,” Sung said. “I have gone to different neighborhoods to knock on doors, just to make sure [AAPI] people were reached. And we definitely could not do that without the support and funding” of the initiative.

Assembled in 2020 as a coalition of 11 state-based organizations, the AAPN strives to politically empower the local progressive organizations working in AAPI communities. As a conglomerate of nonprofits, they provide the infrastructure needed for connecting civic groups and facilitating advocacy. The launch of their most recent campaign not only makes history as the country’s largest AAPI voter outreach program ever launched, but also represents an important, long-term investment in AAPI progressive political power at the local, state, and national level.

In 1993, there were only about four major AAPI civic organizations in the country. Despite a steadily growing population rate and a significant voting gap for the demographic, there were a limited number of political resources in place to engage this group of voters. Sparse campaign outreach, language barriers, and exclusive exit polling practices were all common hindrances to the AAPI electorate.

Today, the AAPN exists as part of a burgeoning political ecosystem of civic organizations hundreds strong has developed to continue addressing these issues, amplifying the 23 million AAPI voices of America’s fastest-growing racial group.

“This is a big thing in my lifetime,” Sung said. “I don’t remember work like this happening when I was growing up.”

Now, the post-COVID political moment presents a unique set of challenges and opportunities for AAPI engagement groups. Increased levels of anti-Asian violence have wracked many communities, spurring narratives of xenophobia and alienation. The Center for the Study of Hate and Extremism found that between 2021 and 2022, anti-Asian hate crime spiked 339 percent. Accordingly, APIAVote’s 2022 Voter Survey reported that “73% of Asian Americans worry about experiencing hate crimes, harassment and discrimination at least ‘sometimes’ and 24% said they worry about it ‘very often.’”

But these experiences have also created a time of critical national attention for the AAPI community, raising awareness for social issues that have inspired a new wave of people willing to help.

The success of the AAPN’s operation will rely on the support of partnering organizations such as Asian Pacific Islander American Vote (APIAVote), said Christine Chen, the group’s co-founder and executive director, who has been championing political change in this field for more than 15 years. Highly familiar with the structural demands of civic advocacy, she emphasized the importance of this network.

“[Policymakers] only pay attention when our community is also voting, so APIAVote in the last decade has been building up that capacity,” she said. “That’s why the Asian American Power Network was created.”

The major financial investment of their latest campaign will help support the efforts of grassroot groups attempting to scale up operations at the state level with measures such as conducting local voter surveys, supporting progressive candidates, and funding civic education programs.

“COVID hasn’t really changed our mission, per se. It’s more about now there’s more people that are actually willing to engage in the work,” Chen said. Tragic events such as the Atlanta spa shooting in March 2021 have become wake up calls for those who never experienced harassment due to their racial identity. “There are so many more people who are asking, ‘What can I do? How can I get more politically involved?’”

The AAPN’s Pennsylvania affiliate, the Asian Pacific Islander Political Alliance, has responded to this influx with public events such as digital organizing classes, community safety forms, and introductory sessions for new volunteers. Trainees are able to build connections with organizers and “move people to action on and offline.”

Jung Kim has been an active volunteer in similar initiatives in Virginia since 2018. Most recently, she has been involved in canvassing programs with the National Korean American Service & Education Consortium (NAKASEC), a beneficiary of the AAPN campaign.

“I’ve been able to knock on a lot of doors and meet a lot of people, and just talk about why it’s important to go out and vote,” Kim said. “When we speak the same language, we connect more. There’s more trust than fear.”

With the boosted support from the AAPN, Kim has observed that there are now more opportunities for diversified outreach. “There are a lot of creative ideas, more ways to get the word out. The old ways work too, but using technology in different ways has been exciting to see.”

The initiatives are unique to every state, but they all serve to empower AAPI constituents to get involved in their communities, whether they are seasoned activists or first-time voters.

“What’s important for people to understand is that this problem is not going away. It's about changing your lifestyle and paying attention,” Chen explained. “It’s really about connecting these dots of what your solutions may be to stop Asian hate and realize that it does circle back to how we build sustainable long-term political power. How do you yield that power as a community in coalition with other communities of color and other like-minded organizations?”

Indeed, as AAPI civic engagement work continues beyond the midterms and gains are assessed, the crux of the efforts to yield this power moving forward lies in the data: its accuracy, analysis, and accessibility.

More concentrated AAPI data analysis in the past few years has, for instance, highlighted the importance of early voting and mail-in options to Asian American voters. Last year, the Center for Information & Research on Civic Learning and Engagement reported that “two-thirds of young Asian Americans voted by mail in 2020, and approximately six in ten say they plan to do so again in 2022,” which was “by far the highest rate of mail-in voting of any racial/ethnic group of youth.” Recent legislation in states like Texas and Virginia threatening eligibility for these options could ostensibly subvert AAPI engagement.

“I talk about [early voting] a lot with people I meet.” Kim said. “For people who are working or just are very busy but want to vote, it’s a great option for them. It’s definitely a very common thing for my community, so access to that is very important.”

Polling is another dimension of engagement with room for improvement. Exit polls and surveys are most often conducted in English, which can be an exclusive factor for AAPI voters who might opt to take them in language. And even when AAPI data is collected, it is often obscured by vague labels like “Other,” or even left out of reports altogether due to a lack of oversampling. According to Howard Shih, managing director of AAPI Data, there is critical information being lost in this process.

“No matter where you look at a particular issue, without the data you aren't able to fully realize the stories and narratives within the community,” he said. “Just being able to build on and expand the capacity for community members to access, understand, and analyze the data that is available to effectively advocate is what really inspires me to do this work.”

Campaigns like that of the AAPN which seek to support accurate and accessible AAPI data, as well as to encourage citizens to be more civically engaged as a whole, are crucial.

“I think there's been a lot of effort to invest in infrastructure,” Shih added. “Organizations like APIAVote and local organizations that are doing civic engagement, certainly are all in a better position to sustain the work that they’re doing.”

Though conclusive racial demographic data from the 2022 midterms has yet to be published, the Pew Research Center has reported that more than 13.3 million Asian Americans were projected to be eligible voters in 2022, a 9% increase from 2018. As the work of AAPI community outreach across the country continues, executives and activists alike share pride and optimism in their movement.

“This same infrastructure is not only the same one getting out the vote or getting out the count for the census,” Chen explained, “but they were the ones doing wellness checks on our community households during the pandemic, making sure that they understand vaccines and, during the rise of anti-asian violence, making sure our communities were safe.

“It's really this time when you’re hit with a crisis, but the community delivered and the infrastructure we created was why we were able to persist and come out even stronger. It just showed what this community is made of.”

“Five years ago, I would not have dreamed of being involved the way I am today,” Sung shared. “I would have never brought up voting or political things in normal conversation, but now I knock on doors and help campaigns and call strangers to talk about voting because I know it matters. And I’m very proud of this organization and the Asian American community. We are making a difference.”