CASHTON - Farming’s future is being shaped in Kori Blank’s classroom.

There are two guinea pigs and a rabbit in an animal lab, a stripped-down tractor in a mechanical room and a walk-in refrigerator and full-size kitchen that come in handy during deer hunting season.

If a kid lands a buck, the students can process it right down to the tenderloin and hot sticks.

Blank, 27, is the agriculture instructor at Cashton Middle/High School, in the heart of Wisconsin’s dairy country.

She’s guiding the next generation of dairy farmers, ag scientists and animal genetics experts. And she's helping countless others understand exactly where their food comes from.

She’s the adviser to the school's chapter of FFA, which used to be known as Future Farmers of America. About one-third of those enrolled in the school participate.

The state’s dairy industry is enduring rugged times. But Blank forges ahead.

"There are a lot of farmers in the area that are still fighting, still trying to keep their farms afloat and feed their families," she said. "I love the dairy industry."

She also loves her job and her hometown, tucked in the Driftless Region of western Wisconsin. She grew up on her parent's dairy farm, which is wedged into a downtown neighborhood and lies just a short walk from the school.

It's a picture-perfect spot: red barn, around 80 cows and an American flag painted on fence slats.

"I always said in college that I'd never teach in my hometown," Blank said.

Blank landed her first school job in Waterloo, and she and her then-fiancé had a five-year plan to stay.

But after two years, Chris Blank got a job in Cashton as a dairy production specialist with a co-op, so Kori moved back home, prepared to take any job.

Six weeks before that school year began, the agriculture education spot opened up. She was the natural fit. She and Chris married in November 2017 and have an 8-month-old son, Jayce.

Economic Insecurity Felt in Classroom

Agriculture education remains a vital part of the curriculum in schools across the state. In Wisconsin, there are 325 ag teachers covering subjects as varied as horticulture, veterinary science and biotechnology.

"Production agriculture (cultivating land and rearing livestock) is still taught, but not as much as it was 30 to 50 years ago," said Jeff Hicken, an education consultant for the Wisconsin Department of Public Instruction.

Blank's teaching career has run parallel to some of the hardest times in the history of Wisconsin's dairy industry, with small dairy farms closing across the state amid low milk prices and a consolidation push.

Ag teachers, Hicken said, "probably know a little more of what's happening in those students' lives," especially in these last years, in the midst of the dairy crisis. The economic insecurity has been felt in the classroom.

In Blank's second year in Waterloo, one company dropped dozens of its milk producers, who then had only 30 days to find a new place to sell milk.

"It was a hard month," she said. "A lot of these farmers were searching and just begging different companies to take them in. Kids were coming to school, knowing mom and dad are stressed and knowing that they have no idea what's going to happen in the next 30 days.

"It was super emotional. ... One of the farmers was someone we used to rent a barn from to put our sheep in. And his farm was one of those that was hit. It was heart-wrenching to go there and see them struggling and trying to figure everything out."

The toughest situation, she said, is when a family has to give up a dairy herd. She worries for those students who have been affected by that loss and tries her best to help them cope. She has seen it happen in both Waterloo and Cashton.

Her students have seen it too.

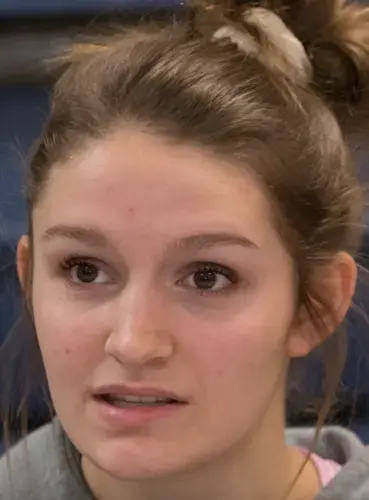

"I think it's hard because their entire way of life just changed," said Brianna Wanek. "And there is no more routine. You're in your house and you're staring at the empty barn. That used to be my life."

'I Do Anything and Everything'

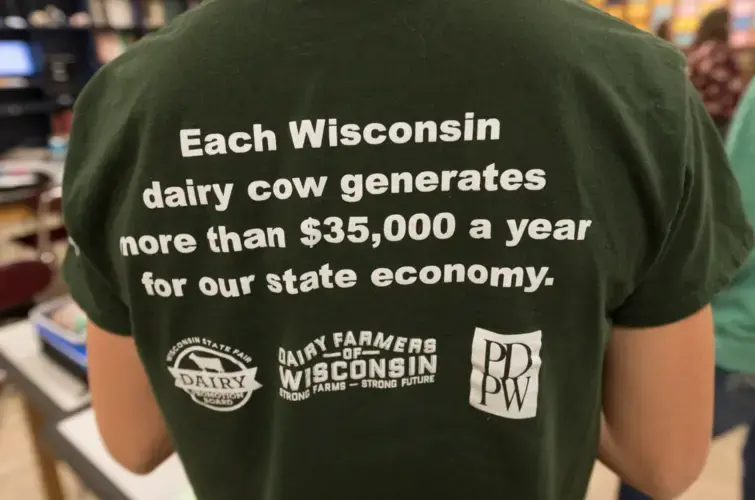

Nearly 21,000 Wisconsin students participated in 251 FFA chapters in the 2018-19 school year. The organization provides leadership opportunities through conferences and career development. It also forms part of the social backbone of communities through fundraisers and livestock shows.

At Cashton, about 100 students participate. It's a hardy bunch, with some fully committed to making farming — dairy in particular — work.

There's Landon Klinge who works on his grandpa's dairy farm.

"I do anything and everything," said Klinge, who one recent afternoon swept up feed and bedded the cows before playing with the school's basketball team.

"I like fieldwork and milking cows," he said.

He believes there is still a place for the small dairy farmer in Wisconsin.

"My grandpa is very good at it," he said. "He's never had a problem with it. He sold the cows 15 years ago when my grandma had cancer so they could pay off the bills for that. And then he bought back 60 cows and has been running strong ever since."

There's Rachel Klinkner, president of the chapter, who has grown up on her parent's organic dairy farm, which has 70 cows, and is part of a large extended family of farmers.

She said the dairy crisis is never far from her mind.

"There are some local families around here that have been going out of business, selling their homes, which has been very hard because they are our family friends, community members," she said.

And there's Wanek, whose dad has a large dairy operation and whose mom works for Organic Valley, a national farmer-owned organic cooperative.

She pitches in with the work at home, waking up at 4:30 a.m. to feed calves.

"I know that there's an overflow of milk in the market and there's not enough buyers for the milk," she said. "That's why a lot of farms are going out of business because they can't find anyone to take their milk."

She has a passion for dairy science and plans to use her college education as a springboard to a career in milk quality or dairy genetics.

"I feel like the future is going to be a lot of big farms and not so many small farms," she said. "Because the bigger farms are going to take up more of the milk space and the smaller farms aren't going to be able to compete."

But Wanek truly believes there will always be dairy farmers.

"No matter the size of the farm, you're still going to get the same essential experience," she said. "You're still going to learn the hard life lessons, like life and death and birth."

Sharing Knowledge With 'City People'

Izzi Mason's father is an English-born veterinarian who emigrated to the area to establish a practice. Mason works part time at Blank's parents' farm, milking cows and feeding calves.

"I really like farming, enjoy being with the cattle," she said. "I want to learn more about dairy science."

She enjoys showing dairy cows and has taken animals the last two years to the Wisconsin State Fair.

"Well, it's really cool when city people ask a bunch of questions about our cows," she said. "It's fun to talk to them, tell them all the things I've learned and seeing them really interested."

For Mason and other students, Blank is a confidante and a guide. She knows dairy farming is a hard life. But it's something she hopes is carried on by her students, if that's what they want to do.

"Yes, they know they're going to struggle, but most of the students that are going into the dairy industry, they know that, they understand that and they've experienced it first hand," she said. "And I think we all can try to be positive and say: ‘There's got to be a light at the end of the tunnel. We've got to crawl out eventually.’ ”

The Next Generation Steps Forward

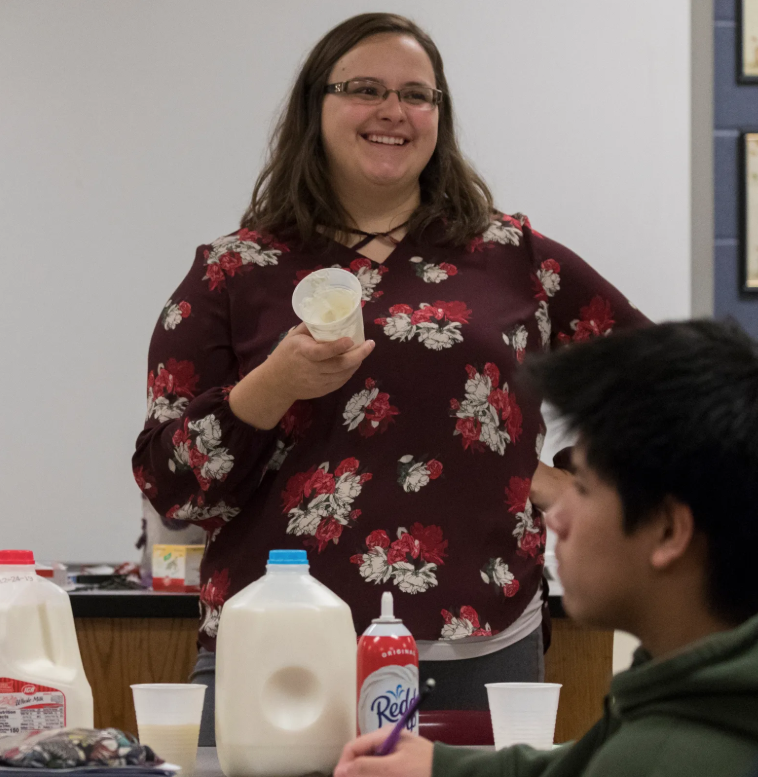

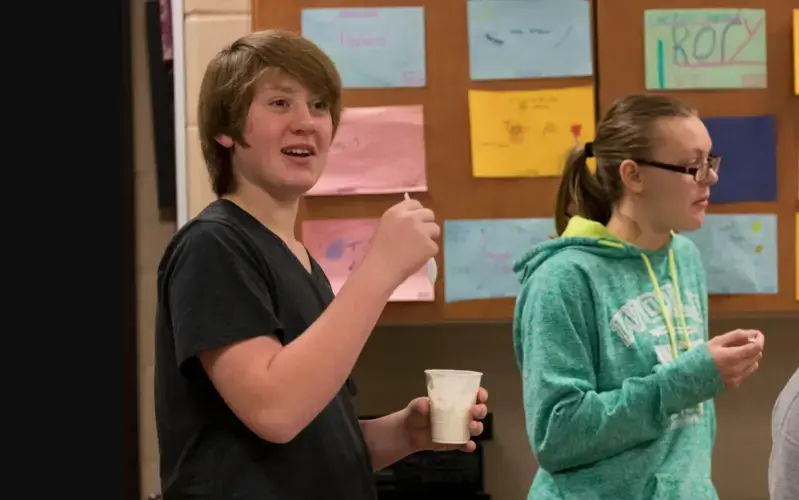

On this day in Blank's first-period class, 10 students are taste-testing 10 dairy products, including three types of milk, sour cream, yogurt and butter. The aim: identify the product by taste, smell and sight.

"It looks gross," one student said of the sour cream.

Blank agreed: "I don’t eat this product, at all."

The kids laughed and learned.

Some of these kids will go into dairy farming, some into the larger agriculture industry, some into something they can't predict right now. "It's up to the kids to make their own way," Blank said.

Blank's older brother is farming with her parents. Others in her generation are also stepping into the family business. If 8-month-old Jayce decides one day years from now that he wants to go into dairy farming, she'll encourage him.

"You do see, the next generation is starting to take over," Blank said.

And what of her own choice to teach students. How long will she do this job in her hometown?

Blank said: "Oh, hopefully forever."