Paul Jereczek doesn't want to be the one who loses his family's farm, not after four generations before him made it work.

He and his father, Ken, milk about 200 cows on land in Trempealeau County that's been in the family since 1873.

The last few years have been challenging, and not just because milk prices have been stuck in an economic valley. The Jereczeks have difficulties finding hired help, too, which means the barn and the fields take over what could be family time.

“Five or 10 years from now, I don’t think we will be milking cows anymore, realistically," the 35-year-old farmer said. "Financially we are fine, but I have four young children who I don't spend nearly enough time with."

Jereczek is trying to build a bridge to the future even as he crosses it. He has planted more than 1,000 hazelnut trees on 3 acres previously used to grow hay — a small piece of the farm that someday could pay off well if the perennial crop takes hold.

Worldwide, Turkey and Italy dominate the hazelnut industry. Domestically, Oregon has more than 800 growers who produced nearly all of the U.S. crop valued at $92 million in 2018.

Hybrids have been developed that thrive in a northern climate and are hardy enough to survive Wisconsin winters. It costs Jereczek about $5 a tree to plant them and there’s nothing to harvest until at least the third or fourth year — which for him is still a couple of years away. But because it takes a while, the marketplace could be less vulnerable to crashing from everyone jumping in at the same time.

The University of Wisconsin and University of Minnesota are collaborating on a "Million Hazelnut Campaign" to plant 1 million trees across the Upper Midwest. They estimated in 2017 the annual net income from fully mature hazelnut trees at between $3,400 and $4,200 an acre. Further, the roots systems prevent erosion, don't need irrigation and are drought resistant.

“Is it going to save the farm? That’s the best-case scenario, but I’m not banking on it yet,” Jereczek said.

Still, he remains hopeful his family's future will unfold on the farm where he grew up and returned to after studying English at the University of Wisconsin-River Falls.

“I want my kids to have a chance to do something with the land, agriculturally, and I don’t see dairy being it, at this level,” he said.

Wisconsin has billed itself as America's Dairyland for nearly a century. But with industrial farms on the rise, its next generation of children may never know what it's like to see red barns and Brown Swiss cattle in pastures on hillsides.

Dairy farmers "are pretty exhausted, mentally, trying to figure out how to survive," said Angie Sullivan, agriculture program supervisor with the Wisconsin Farm Center, part of the state agriculture department, where farmers can get help untangling their finances and managing stress.

Many are also asking themselves whether surviving is enough, whether an operation of 50, 100, even 200 cows is still the best use of their land and talent.

This year alone, about 800 dairy farmers in Wisconsin left the business, a rate of more than two per day. Many had small family farms. They joined an exodus from dairy that has sped up in recent years but has gone on for decades.

Some of those farmers are now growing cattle feed for large dairy operations. Some are raising beef cattle. A few have carved out niches that were a surprise, even to them.

Old farm, new use

Tom Rohland sells wine these days, along with gourmet olive oils and flavored balsamic vinegar.

He also rents out his century-old barn, which once housed 55 dairy cows, for weddings, class reunions, maybe a Christmas or retirement party. His manure storage pit is long gone; it's a fishing pond now.

Every day for about 15 years, Rohland and his family milked cows and tended to their farm in Clark County, where cattle outnumber people 4 to 1. They grew fruit on land not used for cattle feed.

There were good times in dairy, but they were always followed by low milk prices or poor weather for growing crops. It was hard, relentless work. Rohland, then in his 40s, had metal pins and screws in his hands and ankles, the result of farm injuries.

“As time went on, it seemed like it was always an uphill battle,” he said.

With his children grown up and off the farm, and his optimism about the future of small dairy operations drained, Rohland sold his cows.

Relying on off-farm jobs for several years, he and his wife, Sheri, turned their wine-making hobby into a full-time business, Munson Bridge Winery.

“Some people thought we were nuts," Rohland said. "There weren’t any wineries in the area."

But the Rohlands had seen wineries in other parts of the state that were so tucked away in the hills they could barely be found — and those were packed with customers. So they gave it a spin themselves.

"We're still living in the same place with the same buildings, but it's much more enjoyable," Rohland said.

Farming evolving

Before it became the nation’s leader in dairy farming, Wisconsin was known as the wheat state. And for more than 150 years, parts of Wisconsin have grown chewing tobacco, a small-acreage crop that farmers used to say was their "mortgage payment” because of its profitability. In the 1960s, there was a large loss of dairy farms after the industry transitioned to refrigerated bulk tanks for collecting milk, replacing 10-gallon steel cans.

Farming has been evolving since its very beginning, said Dennis Shields, chancellor of the University of Wisconsin-Platteville, which has a large dairy science program.

“We’ve always adapted," he said. "You show me a successful farmer, and I’ll show you someone who is able to adjust and adapt."

But farmers are now engaged in a global marketplace marked by overproduction, fierce competition, changing consumer tastes, mega-size farms and environmental issues. A trade war with China, the European Union or Mexico can upend business for months, even years, at a time.

Given that volatility, one thing seems certain: The small dairy farm from 10 years ago won't be around in another 10 years if it doesn't keep evolving, said Brody Stapel, a dairy farmer from Cedar Grove and president of Edge Dairy Farmer Cooperative. "Adaptability," Stapel says, "is the key."

Wisconsin still produces more cheese than any other state — more even than most countries. But in the last few years, thousands of dairy farmers have lost money practically every day they’ve milked their cows, year-round, as an oversupplied market has kept prices depressed. Many farms milking between 50 and 100 cows are at risk of shutting down because they don't benefit from economies of scale.

“As much as I love small dairy farms, we don’t have very many automobile manufacturers that build 400 cars a year. We did at one time," said Jack Britt, a dairy consultant and professor emeritus at North Carolina State University.

“So, should dairy farmers move to a new enterprise? Yes, but only if they are innovative and willing to learn new methods and systems. I don’t think there is a single crop or area that could replace dairy … but the opportunities are broad if one focuses on the end market or the emerging markets.”

Can you co-exist with a Walmart?

The question for many Wisconsin farmers, then, is how to get from point A to point B.

“I would never suggest abandoning the family farm," said Gov. Tony Evers. "I think it’s still a great possibility, a great job for folks. People who raise their kids on farms will vouch for that."

Evers grew up in Plymouth, a town once surrounded by scores of dairy farms.

“These were good farm families," he said. "They worked hard and were able to make money. We need to get back to that time.”

The problem is farmers have been getting a milk price similar to what it was 30 years ago. Expenses are very much up to date.

Smaller dairies can still survive, but only if their operating costs are low enough or they have a unique product that fetches a higher price, said Steven Deller, an agricultural economist at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. “It’s like, can you co-exist with a Walmart? Yes, you can. But you have to change.”

One of the best ways? "Make sure there are off-farm employment opportunities," Deller said. "It keeps the family afloat, and therefore it keeps the farm afloat” as farmers try new paths.

Not wanting to exit dairy, but disillusioned with milking cows, some farmers have switched to goats. This year, according to the most recent U.S. Department of Agriculture data, Wisconsin leads the nation with more than 72,000 dairy goats, easily topping California which came in second with 40,000, followed by Iowa and Minnesota.

Worldwide, goat milk is more popular than cow milk and it’s gained ground in the U.S. with a changing consumer marketplace and immigrants accustomed to its taste.

Farmers should be mindful of these kinds of societal adjustments, Britt said, and develop products that respond to them.

Not too many years ago, it was generally accepted that small breweries would disappear as large beer makers kept growing, taking control of the marketplace.

"Then," said Jack Uldrich, a futurist from Minneapolis, "there was this explosion of microbreweries."

Diversification key

This year, with $8.8 million in state funding, three UW System schools — Platteville, River Falls and Madison — launched plans for a Dairy Innovation Hub that's expected to create an advanced dairy management academy and improve labs and farms devoted to research.

The hub is looking out 10 or 20 years on "substantial innovations" for the industry, said Scott Rankin, chairman of the food science department at UW-Madison. "The small and medium-size producer is on everybody's mind in these discussions."

UW-Platteville has a 400-acre research farm with a 200-cow dairy herd. It's installing robotic milking machines so that dairy science students can learn by using the latest technologies.

“We are not going to come in and save the farms ourselves. But we are going to help them with the intellectual support they need and we’re going to be the source of the workforce — the people who will manage these farms,” said Shields, of UW-Platteville.

"I think we should be America's Dairyland and other things," he said.

The chancellor said there wasn't much that could be done about small dairy farms already lost. “We can’t sort of resurrect them. But we can make the future dairy farmers much more adaptable and responsive to the cycles in the industry."

Wisconsin, Evers says, needs a diverse agricultural base that includes farms of all sizes. The state ranks first in the nation for snap beans, cranberries and ginseng, third in potatoes and fifth in cherries.

“In our state, one of the few areas making progress, monetarily, is fruits and vegetables," the governor said. "Not everybody can have an orchard, that’s for sure, but I think we need to help all farmers diversify as much as possible."

At the same time, Wisconsin leaders have continued to invest heavily in dairy, even sending trade missions to China and Vietnam to promote products. They may be encouraging diversification, but they're not walking away from a $45 billion industry.

Searching for new revenue streams

Steve Kelm, a dairy science professor at the University of Wisconsin-River Falls, said he's confident dairy farmers will develop new revenue streams inside and outside the industry.

“In California, that was almond trees, walnut trees and grapes in the Central Valley. Wisconsin is going to be similar in that regard, whether it’s ginseng and things adapted to our environment, or berries, or raising dairy beef cattle,” Kelm said.

Already, some of the state's biggest livestock farms are moving into energy production by converting manure into renewable gas.

Smaller farms are diversifying out of commodities markets and into areas such as dairy cattle genetics, raising young animals for bigger farms and producing specialty milk for artisan cheese plants. They're looking at raising alternative crops that are on the rise, such as hemp.

Looking further into the future, Wisconsin may be helped by climate change.

"The biggest impact of climate change is going to be the availability of water," Britt said. "Our forecast is that dairy is going to move north to places that have plenty of it."

Leading dairy states such as California, New Mexico, Texas and Arizona will have difficulties getting enough water. Great Lakes states, including Wisconsin, Minnesota and New York, will be magnets for growth.

That growth, however, would have to be managed — and safe. Some of the nation's largest dairy farms, known as concentrated animal feeding operations, or CAFOs, are in the West. One of them, in Oregon, is licensed for 70,000 cattle.

The average size of a Wisconsin dairy farm is about 150 cows. But that number is rising because the number of CAFOs in the state has jumped 55% in less than a decade to 279 farms.

With so many cattle, industrial-scale farms run the risk of contaminating groundwater and overwhelming lakes, rivers and streams with runoff manure and fertilizer pollution. Rural water-well contamination is under growing scrutiny in Wisconsin.

"There's going to be a natural push by the public and the government to insist that we don't contaminate our groundwater," Britt said.

Cows themselves also will change. Dairy cows of the future will be a milk-producing powerhouse, the result of crossbreeding and gene editing. They will have implantable, microscopic sensors to monitor their health and well-being.

The data will be integrated with information gathered across an entire farmstead, down to the bacteria in soil where cattle feed grows. Farmers will be able to use epigenetics, in which specific livestock genes are turned on or off, to trigger changes in the animal's biology.

"Robots and automated systems will do much of the routine work on farms 50 years from now. This will benefit cows because they crave consistency," Britt said.

Dairy farms of the future could even produce specialty milks that are therapeutic for cancer patients or the elderly. Already, some genetically engineered cows are being used to manufacture human antibodies that could someday be used to treat infectious diseases like Ebola and influenza.

"Give yourself permission to think differently about the future," Uldrich said. "The one thing I say as a futurist is, if your idea doesn't sound crazy, you're not thinking hard enough. If it sounds plausible, it's already happening."

In the Netherlands, the world's first floating dairy farm has been launched in an urban area where rising sea levels have made farmland prone to flooding. The three-story raft, with glass sides, is home to 32 cows. Its electricity is generated from floating solar panels and drinking water comes from a rainwater collection system.

The cows can move freely from their stalls to an area where they're milked by robots. When tides allow it, they can cross a bridge to a dock and pasture, according to FarmingUK, a British publication.

Three companies behind the project are considering a floating chicken farm and greenhouse aimed at providing fresh food for local markets as well.

A nuisance becomes a moneymaker

The move into energy production is a classic example of a new revenue stream emerging from a chronic problem, in this case what to do with the prodigious amount of manure created on livestock farms.

Large-scale dairy farms are harnessing methane in manure and selling it as an alternative to traditional natural gas. For years, some farmers with anaerobic digesters — there are currently about 40 operating in Wisconsin — have tapped the naturally occurring gases in waste to generate electricity, selling what they didn’t need to utilities.

The shift to renewable gas, also called biogas, is being driven by federal and state incentives — and in some cases subsidies. Once the methane is pumped into an interstate pipeline, it’s considered a renewable fuel.

Burning renewable gas, rather than allowing the methane to float into the atmosphere, has appeal to companies that need to meet carbon reduction mandates or want to shrink their carbon footprint.

“We went from something that was costing us money, to getting a check back at the end of the month,” said J.J. Pagel, owner of 5,000-cow Pagel’s Ponderosa in Kewaunee County.

Pagel has a partnership with DTE Energy, a Detroit-based company, which built a system on his farm to help make the methane marketable. DTE transports the methane to a location in Manitowoc County, where it’s injected into a natural gas pipeline.

The company has similar deals with four other farms in Kewaunee and Manitowoc counties and has projects in the works with four more farms, including Rosendale Dairy, the state’s largest dairy farm, in Fond du Lac County.

Creating innovative products

Melissa Hughes, the new executive director of the Wisconsin Economic Development Corp., said one reason she took the job was to address dairy issues.

Previously, she was a top executive at the billion-dollar cooperative Organic Valley, based in La Farge. During her 15-year tenure there, as general counsel, the number of family farms in the cooperative grew from 500 to 2,000.

Hughes said she'd like to help dairy farmers develop markets.

"I don't see any immediate solutions, which is heartbreaking, but I think that looking at the supply chain and creating innovative products is a way to drive prices up for the farmers," she added.

Other states are also trying to find ways to help struggling farmers stay in agriculture.

Vermont, the biggest dairy-producing state in New England, has helped some dairy farmers transition into agri-tourism, growing grapes and producing fruit for hard cider. The legalization of marijuana has created another crop opportunity.

Hughes took over WEDC as it continues to oversee its largest project to date: the massive Foxconn manufacturing plant in Mount Pleasant. That's in line with the agency's typical formula: offering manufacturers loans, grants and tax credits in exchange for creating jobs.

Hughes doesn't see additional loans as especially helpful for dairy farmers. "Just giving them more debt is not a solution," she said.

But the agency could do more to cultivate the next generation in dairy, said Sarah Lloyd, a dairy farmer from Sauk County and a Wisconsin Farmers Union board member.

“If WEDC can give big chunks of money to Foxconn, why can’t it give small chunks to farmers to re-energize their situation?" she said.

From dairy to berries

Rohland, the winemaker, gives some straightforward advice to farmers who want to find that new energy outside dairy. Take stock of your skills and assets, and don't be afraid to try something new. Be careful, financially, and have a backup plan.

"Unless you try, you'll never know," he said.

After nearly 40 years as a dairy farmer, Greg Zwald of St. Croix County never imagined he’d launch a new career.

“I really liked dairy," Zwald said. "I expected to retire from it.”

Zwald was a partner, with his brother, in a dairy operation that expanded to 600 cows and was doing well. But they didn’t agree on how family members would enter the business and it caused friction.

“I decided it was better that I leave, rather than try to push my way, my thoughts,” Zwald said.

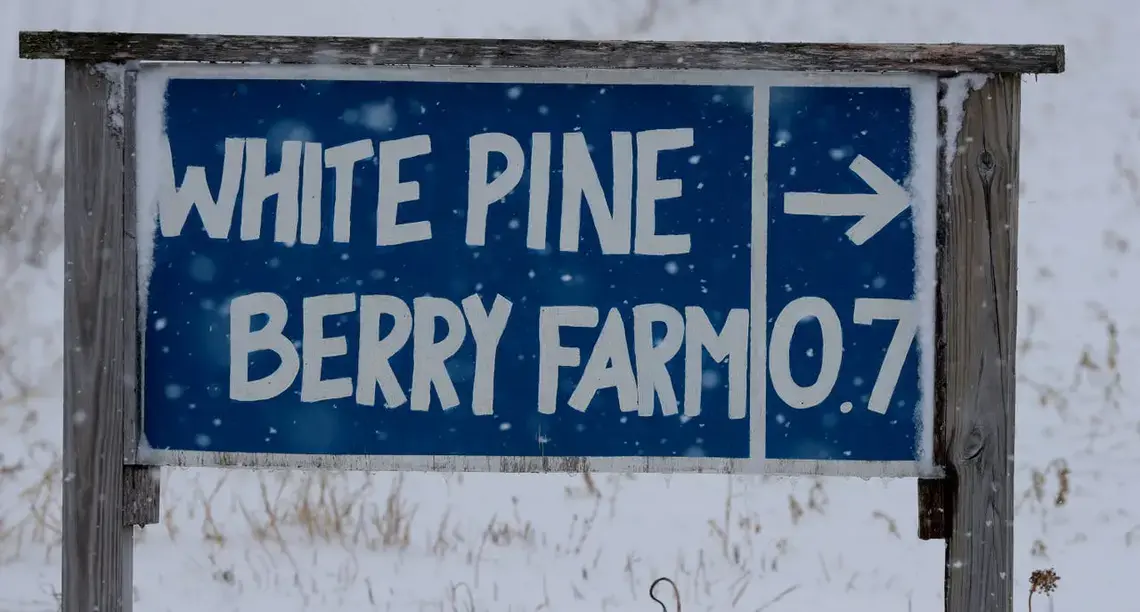

Now, he and his wife, Irma, own White Pine Berry Farm, which sells fruits and vegetables to the general public. They also have a corn maze and pumpkin patch in the fall.

There was some culture shock going from running a large dairy farm to managing a pick-your-own berries operation.

"You've got to like people and you have to assume that some of them are going to step on your berries. But one of our goals is to get kids, families, to the farm so they understand this is where their food comes from," Zwald said.

Starting over wasn't easy.

“Financially, it’s been kind of break-even. But this year was good, and we’re adding a building that will have a retail center in it,” he said.

Zwald has picked up a job managing the UW-River Falls research farm, keeping him involved with livestock.

For most of his life, his income was at the mercy of commodities markets. Dairy farmers don't know what they'll get paid for their milk until 30 days after it leaves the farm.

With the UW-River Falls work, Zwald said, “I am actually getting a regular paycheck for the first time in my life and I have more free time."

Challenging times

Wisconsin's remaining dairy farm families are remarkably resilient. They weathered the Great Depression and the milk strikes of 1933. They've toughed it out through numerous downturns, recessions, poor crop years, trade disputes.

“I wouldn’t bet against anyone who, for the last four years, has gotten up at 5 a.m. on Christmas Day to milk cows and provide for their family the best they can,” said Kelm of UW-River Falls.

What's been different about the recent downturn has been its duration, five years, and its severity — the highest number of dairy farm losses in Wisconsin, on a percentage basis, going all the way back to the Great Depression.

"I think a lot of farmers have already made the choice to quit. They are going to milk cows until their feed is gone and then they're done," said Travis Tranel, a dairy farmer and Republican state representative from Cuba City.

"It's been a challenge and the next six months could possibly be the biggest challenge. It's going to be a long time until May," Tranel said.

He's particularly bothered when he hears that young people don't want to farm anymore. "That could not be further from the truth. They want to farm, but they just can't afford it," said Tranel, whose family has a 600-cow organic dairy.

The loss of dairy farms is especially noticeable in southwest Wisconsin.

"Drive around any of these smaller towns. The banks are closing, the car dealerships are closing," Tranel said. "As I drive by those red barns, I always smile and think those were the good old days when a mom and a dad probably raised five or 10 kids in that house on 150 acres and they milked 40 cows. As those barns come down, my kids aren't even going to know that's what Wisconsin used to look like."

The losses could have far-reaching consequences beyond rural communities.

“The success of this nation is because pretty much nobody has to worry about where their food comes from," he said. "If we have gotten to the point where the very people who have made us successful can no longer pay their bills, I think we really have to question if that’s OK.

"As a society, I hope that we don't find it acceptable."

Hopeful for the future

Some might think that what Jereczek has done, planting hazelnut trees, goes against the grain of Wisconsin dairy tradition.

But the Jereczeks understand tradition. Paul’s great-great-grandfather, Jacob Jereczek, moved to Trempealeau County in the early 1860s from Poland. After the Civil War, he and his sons bought three farms and were among the first immigrant families to settle in the area.

Paul and Ken have kept the farm current, investing in technology such as automatic calf feeders and health monitoring devices that are attached to the cows’ ankles.

They understand that every generation in farming has its challenges. But the record amount of rainfall this year, which kept farmers out of the fields for spring planting and ruined some of the harvest, reminded Paul why he planted hazelnut trees — a crop that keeps on giving year after year once it gets started.

“I am hopeful," he said. "I think it’s a worthwhile investment.”

He’s recycling dirty livestock bedding from the dairy to fertilize the trees.

The worst-case scenario, if the market for hazelnuts in Wisconsin fails to materialize?

“I will have a bunch of nuts to feed to the cattle,” he said.

These days, a dairy farmer can't afford to waste anything.

Lee Bergquist of the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel contributed to this article.