DOHA, Qatar — They were without money, without jobs and unable to go home.

Twenty Nepalese men who had come to Qatar for work were suddenly stranded in the desert, unable to speak Arabic and even denied access to their passports.

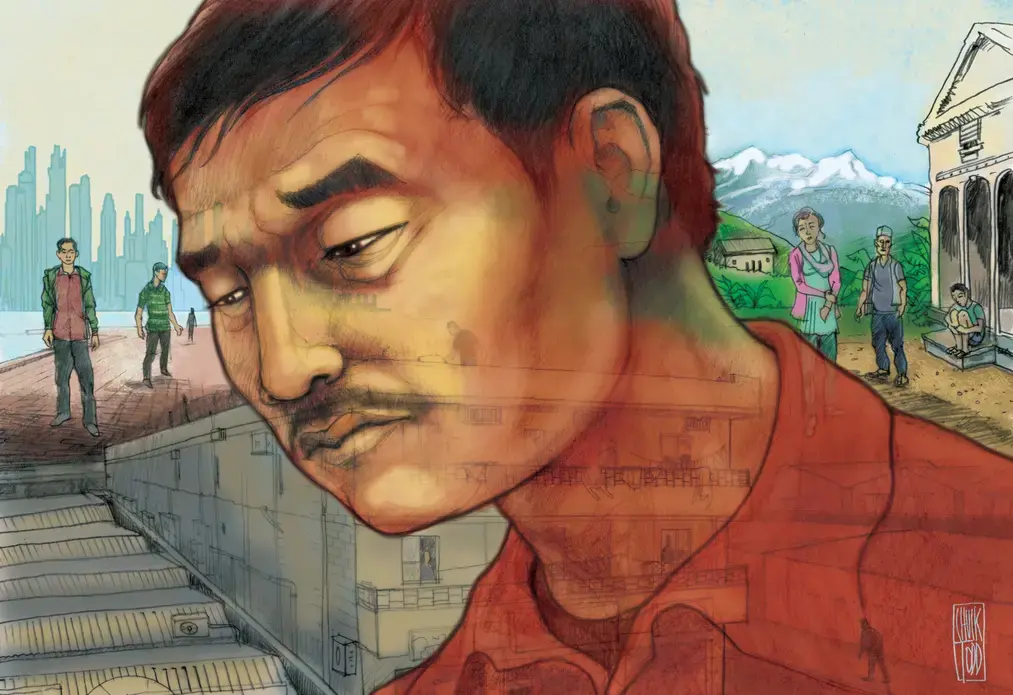

Jiban Prasad Khatiwada was one of them. In March, he and his co-workers discovered that their company, Shaji Al Makhalas General Cleaning Company, had been sold.

His manager left for vacation, but then two weeks later a new man came to their labor camp and told them he was their new boss. He offered them a fraction of their previous monthly salary—700 riyals ($192) for 10-hour days, instead of 900 riyals ($247) for working eight-hour days, Khatiwada says. There would be no overtime pay or food allowances. Plus, the men were owed three months of back pay, and there was no sign that they would ever receive it.

The men refused, but the company still had their passports. And without jobs, their legal status in Qatar was jeopardized.

"Our situation was so bad," says Khatiwada, who was first interviewed near the labor camp where he lived in the Al Khor area north of Doha, Qatar's capital city. "We had nothing. We did not have money to buy food. We do not even have money to give a missed call back home."

When they took their case to a court in Qatar in an attempt to demand that the company return their passports, which had been surrendered when they arrived in-country, they were told that the company, which was listed on the men's visa documents, didn't legally exist. And since it didn't exist, the men couldn't pursue legal action against it.

"We were shocked," Khatiwada says. "We were lost."

Their dilemma is a common one for the estimated 1.9 million Nepalese workers who live abroad. Qatari laws, which include the rigid kafala system in which employees are bound to their employees, and Qatari companies have been widely criticized for exploiting foreign workers. But that exploitation starts close to home, when the men sign on with employment agencies (known locally as manpower agencies) that peddle them into inhumane situations, for a profit.

The workers' recourse is limited: Of the men who make it back to Nepal, few have the wherewithal to file the necessary paperwork and then remain in Kathmandu, the capital city, to see the case through.

Many illegal manpower agencies have been shut down by the Nepalese government in recent years, but even the legal ones are known to engage in practices that take advantage of workers. Since late 2008, nearly 10,000 formal complaints have been filed in Nepal against manpower agencies operating legally there. Advocates of migrant workers say that number represents a small fraction of the complaints that could be made, if workers could more easily make them.

"The process is too long and workers don't have money," says Krishna Prasad Neupane, coordinator of the People Forum for Human Rights, which provides free legal aid to migrant workers.

Other workers who might file complaints are in Qatar, like Khatiwada and the other men in his group, bound by the kafala system that systematically bars them from leaving the country when they choose.

Global Press Journal traveled to Qatar to find men who, after contracting with Nepalese manpower agencies, were stuck there, unable to return home even when they wanted to. Speaking in Nepali, the men told their stories to GPJ's Nepalese reporters in restaurants near Qatar's infamous labor camps and in taxis that circled them.

Editor's Note: The full multimedia article including special podcasts by Global Press Journal can be read here.