That is what the assignment in Panama felt like.

Every time I would set up my camera to shoot a scene of Cuban migrants sitting around the camp talking or just relaxing, they would immediately get up and leave.

I never really thought about the fact that these people were afraid. Afraid of being deported back to Cuba. Afraid of what the consequences of their face appearing in a foreign publication might be. There was also the question of trust.

Many times folks would ask not to be filmed or photographed. My colleagues did not seem to have as much problems as I did. The camera made all the difference in the world.

Those who spoke to us on camera knew that they were taking a chance. Talking to us about their condition in Cuba and the reasons they decided to risk it all on this seemingly endless journey would not sit well with the Cuban government and, if returned, they would be singled out and punished.

Was this series of reports really going to make a difference?

I was especially touched by one young man's story of hardship and perseverance.

Otoniel Tápanes Fleites, a car mechanic and chauffeur in Cuba risked it all by leaving the island bound for Guyana. Final destination: the USA where his brother lives.

He endured many hardships on his journey through the jungles in Venezuela, Colombia, and the notorious Darién Gap in Panama. He was even struck down with malaria during his journey.

When he finally made it out of the Darién jungle, he got word that President Obama had gotten rid of the "wet foot, dry foot policy" and his dream of reaching the U.S. vanished.

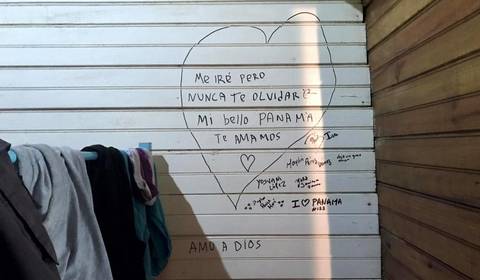

Otoniel is currently living in hiding in Panama City fixing cars on the side to earn money so he can send it to his family in Cuba. If he gets caught by the police he will be immediately deported back to the island. He hopes to ride out the current situation until someone decides what's going to happen to the Cuban migrants stranded in Panama.

During the interview, I asked him what he tells himself every morning to stay motivated.

His reply: "Everyday I wake up and give thanks to God that I am alive. And then I go to work. I have to keep moving forward to see how far I can get while a decision is made on our fate. Perhaps my future is not in the United States. Maybe it will be in Canada, wherever they decide But I can't imagine it will be in Cuba.

"If that is where I end up, well, I hope I can at least go with $200 in my wallet," he said. "That is nowhere near what I spent. Or the time that I have lost. Or the struggle I've been through. But I want to have something I can give my family. At least to be able to say, 'Look, this is all I could bring.'"

As I edited the footage of his interview, I could not help but wonder: What would I do if I were in his shoes?