It was late afternoon, and visiting hours at Alcaçuz Federal Penitentiary had just come to an end. Cecilia* was at home when her phone started buzzing nonstop. It wasn’t her day to visit Junior*, her boyfriend of eight years. He was serving time at Alcaçuz, the maximum-security prison in Brazil’s Rio Grande do Norte state.

The messages started to pour in. A rebellion had broken out at the overpopulated prison.

Cecilia knew many women would be exiting the gates that Saturday in January 2017. They would be visiting their boyfriends, husbands and sons, held at one of five pavilions at Alcaçuz.

Cecilia ran to the front gates of Alcaçuz, hoping to find out if Junior was still alive. The prison was a short distance from her house—she could get there on foot in less than two minutes—but by the time she arrived, she was out of breath. Panic and the biting afternoon sun took everything out of her.

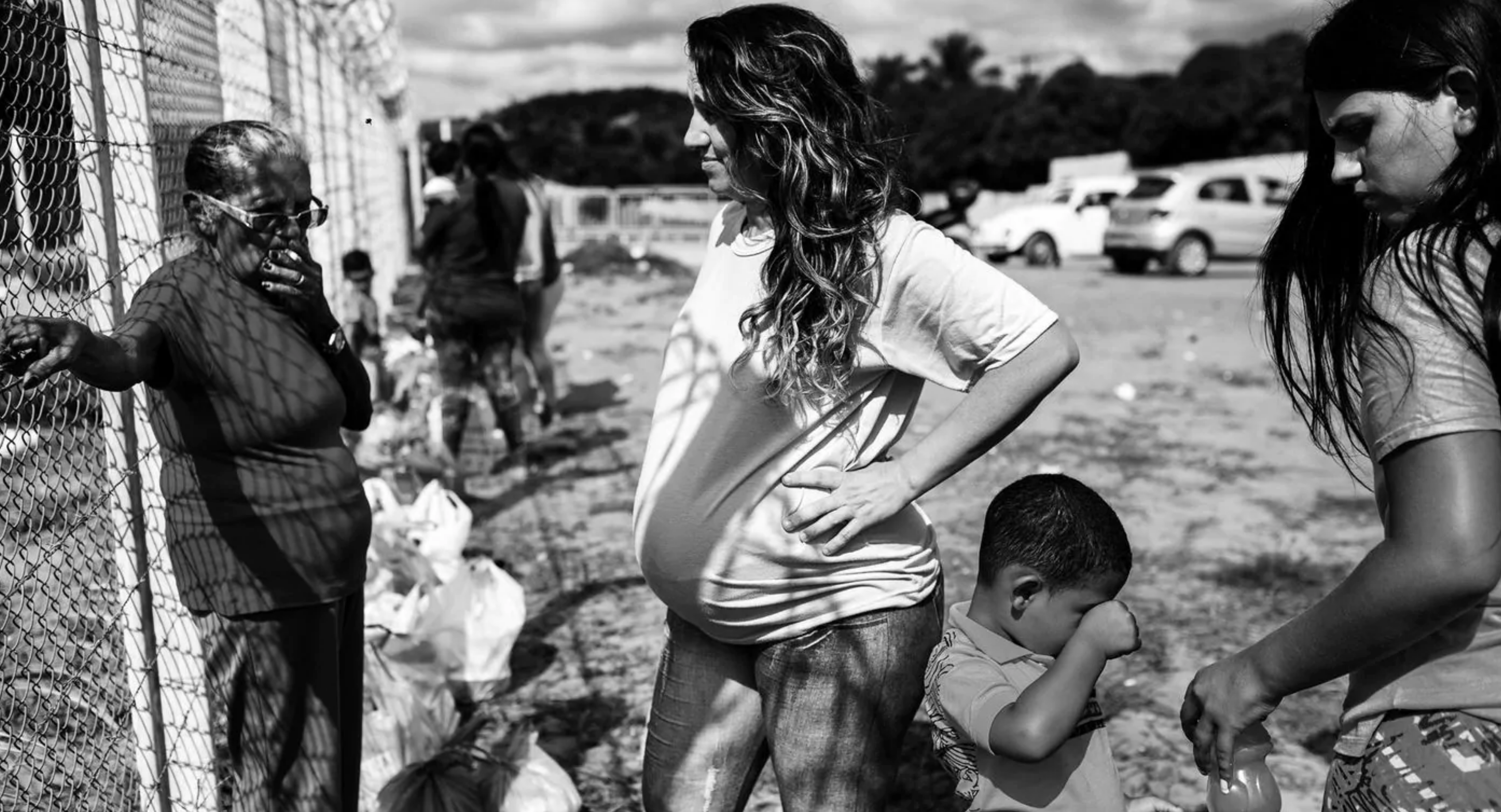

None of the women who had been inside for visiting hours knew what had happened to Junior. From the outside, the women could hear chaos erupting within the walls of the prison as the men begged for their lives and screamed for help. The guards refused to give them any information. When the women started to shout at them to do something, they were met with pepper spray, tear gas, batons and rubber bullets.

Cecilia and the other women refused to leave the gates until they got answers. They protested for days, some setting couches and old pieces of wood on fire to block the road to Alcaçuz. They wanted someone — anyone — to pay attention to what was going on inside. Laura*, whose husband was incarcerated, turned the house she rented across from the prison gates into a meeting place for women. Many, including Cecilia, moved in to be closer to the protest. They wanted to be able to check in on the well-being of their loved ones.

Later, news of what had happened spread: Members of one gang had invaded an area of the prison where a rival gang was held, using homemade machetes to kill those who got in their way or didn’t manage to run fast enough to escape. At least 26 would end up dead over the span of several days before guards and police could regain control of the prison. Most victims were cut into pieces or beheaded. Some of their bodies were burned beyond recognition.

About four years before the riot, Cecilia left her home in Natal, the capital city of Rio Grande do Norte, for Hortigranjeira, a community of about 700 in the town of Nísia Floresta. She wanted to be closer to Junior, who went to prison after being charged with robbery and homicide. Hortigranjeira was as close as anyone could get to Alcaçuz: The prison wall is essentially in some people’s backyards.

After the riot, Cecilia stayed at Laura’s house for a couple weeks. Cecilia knew Junior had survived the riot, but she wanted to remain close in case something else happened. She spent most of her time in a room praying, a practice she took up after spending more than two years in prison for drug trafficking. When she did leave her room, Cecilia would see Maria Clara*, a woman who liked to stay in the kitchen, making lunch for the others and watching TV. Maria Clara’s longtime boyfriend, Ronaldo*, was in prison for robbery charges.

The two women, both 47, likely never would have spoken if it hadn’t been for the rebellion. Neither Cecilia or Maria Clara remembers the moment they first met, just that they always saw each other at the gates of Alcaçuz while they waited to enter the prison on visiting days. Maria Clara used to think Cecilia was uppity. Cecilia thought Maria Clara was too loud and angry.

But at Laura’s house, they began talking to each other. They understood each other’s fear.

Cecilia moved back to her house later that January, once the rebellion was under control and she knew Junior was safe—relatively speaking. Accusations of torture by guards would only grow stronger after the rebellion. Maria Clara stayed much longer, fearful of what might happen to Ronaldo. After other inmates pulled Ronaldo up and over the prison wall to escape the attack, he fell into a ditch. He was considered lucky to have only broken his teeth.

Maria Clara couldn’t bring herself to go back to her home in Natal, where she had first met Ronaldo.

It wasn’t love at first sight for Maria Clara and Ronaldo. The two lived in the same neighborhood in Natal, and they met during Carnival in 2007. They were both working as cordeiros, a type of human rope joined at the hands meant to keep festivities from spilling out onto other streets. It was one of the hottest days of the year and she couldn’t believe he was wearing a wool toque. She laughed to herself and thought he must be a criminal.

It took almost two years for Maria Clara to change her mind about Ronaldo. She met him again after befriending his sisters. They exchanged only a few words. Maria Clara still can’t explain it, but one look and a dance turned her hate into love. When Maria Clara first fell for Ronaldo, she didn’t know that he had already spent time in prison. He ended up back behind bars soon after they started their relationship. He had escaped once before, so this time he had to serve his time in maximum-security at Alcaçuz. For a couple years, Maria Clara remained in Natal.

But after the riot, Natal seemed like a world away from the life she was living. By the time Maria Clara decided she had overstayed her welcome at Laura’s house, it was May. She decided to stay in Hortigranjeira and moved in with Cecilia.

It’s March 2018, just over a year since the rebellion, and Maria Clara is in the kitchen at Cecilia’s house.

“Do you hear that? It’s training time again,” she says. Sun pours in from the kitchen window, its wooden shutters open.

Several loud pops are heard in the distance. The gunshots are close, but Cecilia doesn’t open her eyes. She leans forward slowly, spreads nata on a cracker and takes a bite.

“It’s the same thing every day,” she says, as the shots continue to echo outside. “I don’t even pay attention to it anymore.”

Hortigranjeira would be a typical sleepy community if Alcaçuz wasn’t its neighbor. Doors are never locked and evenings are for catching up with neighbors or going to church. Kids zoom by on bicycles and neighborhood dogs stretch their legs in the sand after long afternoon naps in the shade.

The gunfire dies down as Maria Clara scoops beef stew and rice onto a clear glass plate. They’re training new guards in pavilion four, she says. It’s been empty since the rebellion.

Cecilia sighs.

Handfuls of other prisoners’ wives used to live in Hortigranjeira too, but homeowners stopped renting to them after the rebellion. The women were too much trouble, they said. Maria Clara and Cecilia were lucky to be able to stay. Cecilia is well known in the community for being an evangelical Christian and living a quiet life. The women have never had the police search their home for drugs, unlike others.

“Some of the other wives end up involved in whatever business their husbands are in, or are at least accused [of], but I’ve always kept away from that kind of thing,” Maria Clara says. “I don’t want that kind of trouble.”

While living close to Alcaçuz has its benefits, it also makes escaping being labeled “the prisoners’ wives” that much more difficult. The two women have made some friends in Hortigranjeira and are friendly with several neighbors, but being the only two left in the community with such strong ties to the prison sets them apart. The few other residents who know someone who is locked up don’t like to talk about it. They say they’ll never visit their cousins, nephews or grandsons inside. It’s too painful.

But the presence of the prison itself doesn’t bother most residents. In fact, they like living there because of it. Without the economy the prison brings to Hortigranjeira — residents often provide rides to those living in other towns on visiting days or sell specific items that are allowed inside the prison — many wouldn’t be able to maintain their households. There’s also a sense of security in the community because of the constant presence of guards and police. If a prisoner escaped, they say, the last place he would stay is Hortigranjeira.

When Cecilia and Maria Clara aren’t working or visiting their husbands, they wait.

When they do work, they sell hot meals to order — rice and beans with beef or chicken and a salad — to women who have traveled long distances to visit inmates at Alcaçuz. Long bus, mototaxi and car trips to the prison and the hours-long wait in the sun to enter the gates make it difficult for people to bring food they prepare themselves. Last week, Maria Clara and Cecilia profited about 160 reais, which is about $43.

“We don’t do it for the money,” Cecilia says. “It brings in enough, and it helps others. I always use top quality ingredients because that’s what I would want for my husband. Other people’s husbands deserve the same.”

Cecilia and Maria Clara only sell the meals at their improvised stand, located at the back gates of Alcaçuz, on weeks they consider “theirs.” Prison visits are once a month for inmates without small children, and the weeks and days are divided by pavilion and cellblock so that rival gang members aren’t in the yard at the same time. When it’s not their week, they prefer to stay away.

“We could go, but the women visiting on those days just yell at us and call us names,” Maria Clara says. “And then I’ll just lose my cool, and I don’t want to do that. I don’t want to fight. I just want to live in peace.”

Maria Clara and Cecilia pool their money together each month: food sales, the social assistance Maria Clara receives, and Cecilia’s earnings from reselling clothing in Natal. Some months are tight, and Cecilia says there have been times she’s worried about paying the rent.

“My kids worry about my life here. They want me to move back [to Paraíba],” Cecilia says. “I miss my family, my grandkids. I’m not living for me. I’m living for his life.”

But Maria Clara and Cecilia count themselves lucky to live so close to the prison. Without Hortigranjeira, they wouldn’t make money from the hot meals they sell at the gates. If they didn’t live nearby, trips to Alcaçuz would also cost them: More than one of the women they’ve met while waiting to be called in by the guards have lost their jobs. Visits often run late, and bosses don’t tolerate missed shifts.

Maria Clara sits on the front porch of the restaurant next to the front entrance of Alcaçuz, the back of her chair up against the concrete wall. Today is visiting day for inmates in pavilion three who have children under 12.

While the other women get ready, Maria Clara smokes a cigarette. Ronaldo was moved to pavilion five after the rebellion, so she won’t see him today. He’s been in prison for 10 years now — their whole relationship.

Cecilia doesn’t usually go to the restaurant with Maria Clara, but today she’s decided to come along and sits next to her at the table. As the others rush to change diapers and make sure the food and other items they’re bringing in are properly labeled, a young woman asks Maria Clara to hold her baby girl while she fixes her hair.

“Did you know I’m finally getting married next month?” she says, a broad smile on her face. “I have no idea what I’m going to wear yet though. I have to find the perfect dress.”

“Have you seen Cecilia’s dress?” Maria Clara asks. “It’s beautiful, and she’s renting it. Show her, Cecilia.”

Cecilia hands over her phone. She’s posted her favorite pictures from her wedding on Facebook.

“Oh, I definitely want it,” the woman says, her baby back in her arms. “Send me your bank account information and I’ll transfer you the money.”

Maria Clara and Cecilia both got married on Feb. 24, 2018, when the pastor came to Alcaçuz to perform ceremonies inside the prison. To marry Ronaldo, Maria Clara chose a simple, short white dress with a crocheted top. For her union to Junior, Cecilia wore a long, traditional A-line gown with pickups on the skirt. Both men wore suits for the occasion.

Cecilia never expected to marry Junior. She was separated from her first husband, who she was still in love with, when she met him at a forró concert in 2009. The two had mutual friends and ended up having a drink together outside. Junior was sure he could make Cecilia forget about her first husband. He ended up being more of a parent to her children than their biological father.

She had her suspicions that he was involved in something illegal, but he always denied it, insisting his only income came from the store he owned. She found out he was a bank robber the day he was arrested. He still has more than 20 years left to serve on robbery and homicide charges, but she’s willing to wait. It worked for Maria Clara. Ronaldo was released from Alcaçuz in June. The couple already moved back to Natal to restart their lives, far from the prison.

Stories of men leaving their wives when they get released don’t worry Cecilia.

“I’ve uprooted my whole life to be here. Absolutely everything,” she says. “But I’m not afraid of him leaving me, because I’m with God. Even if he were to go, I would be fine without him.”

*Names have been changed for the safety and protection of those involved.