My full name is Imran Mohammad Fazal Hoque, although I normally shorten it to just ‘Imran’. I was born to stateless Rohingya parents in Rakhine State, Myanmar, 26 years ago. They had never gone to school, and they shared very simple dreams. Their main concerns were to provide three meals a day for their children and for each of us to be safe. There was no thought of dreaming of anything different, even for us—their children. Everything was black and white. There was no room to think about the ‘whys’; in fact, we were unaware the concept of ‘why’ existed.

It feels eerie to be in a world that, until a few years ago, I didn’t know existed. I am an adult now and finishing my second year of college at Harry S. Truman in Chicago. I had received no formal education prior to 2018. Most of my classmates treat me like a normal student and think that I studied at a good university. When they become friends with me and see my writing, particularly on social media, they are amazed by what I have experienced. They ask me many questions because they can’t comprehend the world I came from. How could you have a normal soul after enduring so much cruelty? I understand people struggle to believe my story because at times I can hardly believe it myself.

I took sociology, international relations, and English classes in the fall of last year. This changed the world for me. There are no straightforward answers anymore. During my entire semester, I was encouraged to illustrate why something was white or black. I was asked to prove everything I said or wrote, with evidence in detail. The process helped me see things through different lenses and altered my sociological perspective and imagination.

For my values and beliefs to improve, I question everything that seems unquestionable. If I don’t go down this road, I won’t be able to acquire knowledge of social order, social change, and social inequality, and law that is systematic, comprehensive, coherent, clear, and consistent.

It is so important to have the ability to bring a real picture to our imaginations and to think critically and intellectually. It is the backbone of any society. I see how Myanmar’s government has planted the seeds of persecution against Rohingya for decades. To paralyze our population, it snatched our citizenship rights in 1982, restricted our movements, and deprived us of gaining an education. The government has instilled fear in our society in their attempt to control every aspect of our lives physically and emotionally. Our own villages have become like open prisons for us.

On my journey to the position I find myself in today, which began when I was 16, I have seen horrors—one after another. I grew up in fear of oppression, which I could not find the correct words to describe. One generation is passing down the fear to the next generation. My father gave money to the Nasaka [local military] so they stayed away from our family. Once this bribe could no longer be paid, there was a knock on our door. My father’s last word that night to me was ‘go,’ and I ran for my life.

With great trepidation, I scurried through the thick black veil which was the night. I had not had the chance to look at my home for the last time, nor could I say goodbye to my beloved mother. My belongings were a piece of sarong and a t-shirt as I stumbled into the unknown.

I joined other villagers and boarded a boat to Bangladesh. From the beginning of this journey, I realized that I could only think about myself; how I would get to the boat and cross the border. It felt like I would put my feelings, my compassion, and my humanity behind me if I wanted to survive and make it to the end without knowing what would happen during this deadly ocean journey. My education in life began as I started reading people’s lips, eyes, and body language to figure out who I should talk to, sit next to, and trust.

We arrived in Bangladesh just before sunrise and walked through the jungle to go to the people smuggler’s house. The tiny house was crammed with people, and I was so hungry but my hunger was overwhelmed by the stench of so many bodies in such a small space. Even though everyone’s stomach was empty, and we were dehydrated, we were still conscious and all we could think about was getting to the next boat.

The day finally arrived and we fought our way through the densely forested terrain of the mountain in the dark. I knew some people would not make it, but the lesson was not to look back, and I walked as fast as I could to get a spot on the boat. The boat was packed with hundreds of people with very little food and water. We were floating on the ocean for 15 days, during which time some people died. We threw them overboard.

We reached the Thailand border a few times but turned back and were shot at on our final attempt. We reached a mountain very close to Malaysia. We sheltered in the smuggler’s hut in the jungle. They were collecting money from everyone because we needed another boat. When they secured the money, the boat was arranged but some were left behind. We walked through the mountains in the dark.

The men were at the front and the girls were with the smugglers. My heart was hurting because I could hear the young Rohingya girls crying as they were being raped. I wanted to help the girls that couldn’t walk, but I couldn’t. I had to stay with the group. I had to hurry and not lose the people I was walking with. I just couldn’t imagine how the smugglers could think of their sexual pleasure in that situation as it must have been like taking advantage of a dead body.

We made it to the mainland, and I was delivered to my cousin in Penang. I was treated like a slave of the construction industry. Rohingya were not allowed to work, get an education, or do simple things like setting up a bank account. The constructors hired illegal immigrants like Rohingya because they could pay them very little, exploit them, and threaten them if anyone dared to raise their voice against them.

Almost everyone was illiterate, and if I had just a little education, I could become the chief of the construction area. While everyone was busy playing under the street lights, drinking sweet tea, and trying to hide in the mountain at night, I talked to the managers. Some were Rohingya and others were Indonesians, Bangladeshis, or Vietnamese.

I developed the desire to learn and watched kids going to school on the street. I heard about Australia and thought school would become a reality for me there. I started looking for smugglers, a boat, and money to cross the border to Indonesia and then Australia.

My Rohingya relatives connected me with a smuggler and gave him my number. I was told to be in front of a supermarket at 8 pm. Some other Rohingya and I were walking around anxiously. The smuggler came and collected all of us without saying a word. We escaped from Johor Bahru, Malaysia, to Kendari, Indonesia, by small fishing boat. I couldn’t speak their language but could read their body language and learned how to sense trouble.

We were at a remote village called Kendari, Indonesia, waiting for a boat to go to Australia. The police came one night when the smugglers left the house. My friends and I hid behind the toilet and then kept running by the seashore to hide in the mountain. I was scared to death and urinated in my sarong several times. When the police left, one of the Rohingya was searching for everyone with one of the smugglers. When we heard him talking in Rohingya, we came out and went back to the house. Everything looked very strange, and I couldn’t sleep that night. I was looking through the windows at 5 am and the whole area was surrounded by police. They knocked on the door at 6 am. No one could escape.

We were taken to a police station and transferred to the Manado immigration detention center. I was searched like a criminal and tears were dropping from my eyes like water falling from a waterfall. I had no contact with my family for months and I was to discover later they believed I had died. There was nothing for us to do except stare at the thick bars all day and night long.

The immigration prison where I was held was near the top of a mountain. The view from our tiny rooms was spectacular, and I would wake up very early in the morning to watch people walking up and down the hill. I wished I was a butterfly so I could fly over the tall walls and see the world. I always told myself that I would be free one day. I just didn’t know how or when it would happen.

I immersed myself in my imagination as this was something I could control. I could be a bird, ant, or free human. I would come to sit next to the guardhouse in the morning where I could see the street through the three giant doors. I imagined being out there, walking on the pavement, crossing the road by stopping the vehicles. It invigorated me and helped me see positivity in a setting that was filled with negativity and pain.

I met an Afghan refugee who was an English teacher in his home country. He used to teach his friends English in the camp. I joined them and communicated with him in Urdu. I learned the English alphabet and a few words every day. It boosted me with joy deep in my heart, yet no one saw this. I made a very tiny table to study. I knew I was in a lot of emotional pain, but my brain cells could only focus and process the words that I was learning. Almost two years flew by in the blink of an eye.

I was interviewed by the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees after a year. Seven months later, an immigration officer at my detention center handed me a piece of paper. Written upon it was my refugee status; it just blew my mind how much power a paper could hold. It allowed me to leave the thick bars and monstrous doors behind. I was released in Makassar city in Indonesia.

I was free in the community, but I was not allowed to do anything in Indonesia. I felt the monotony and hopelessness. I had suicidal thoughts. The desperation of ridding myself of the label of ‘stateless’ revolved around my head. I went to Jakarta and flouted around in smugglers' houses for a few weeks. The trucks were arranged, and we were piled onto them like rice bags. We drove through the mountain valleys. The sun was rising, and we were at the top of the hill. We were escorted by the smugglers and whatever money we had was taken. We found out that the helmsman wasn’t there and there was no food and water. There were two Indonesians who were meant to help the captain.

We had no choice except to trust a piece of wood with our lives to bring an end to our statelessness. There were 200 people on the boat and, somehow, we survived the frightening waves. Our boat was met by the Australian Navy, and we were taken to the Christmas Island detention compound, where I remained for six weeks. I believed this would be the end of my suffering.

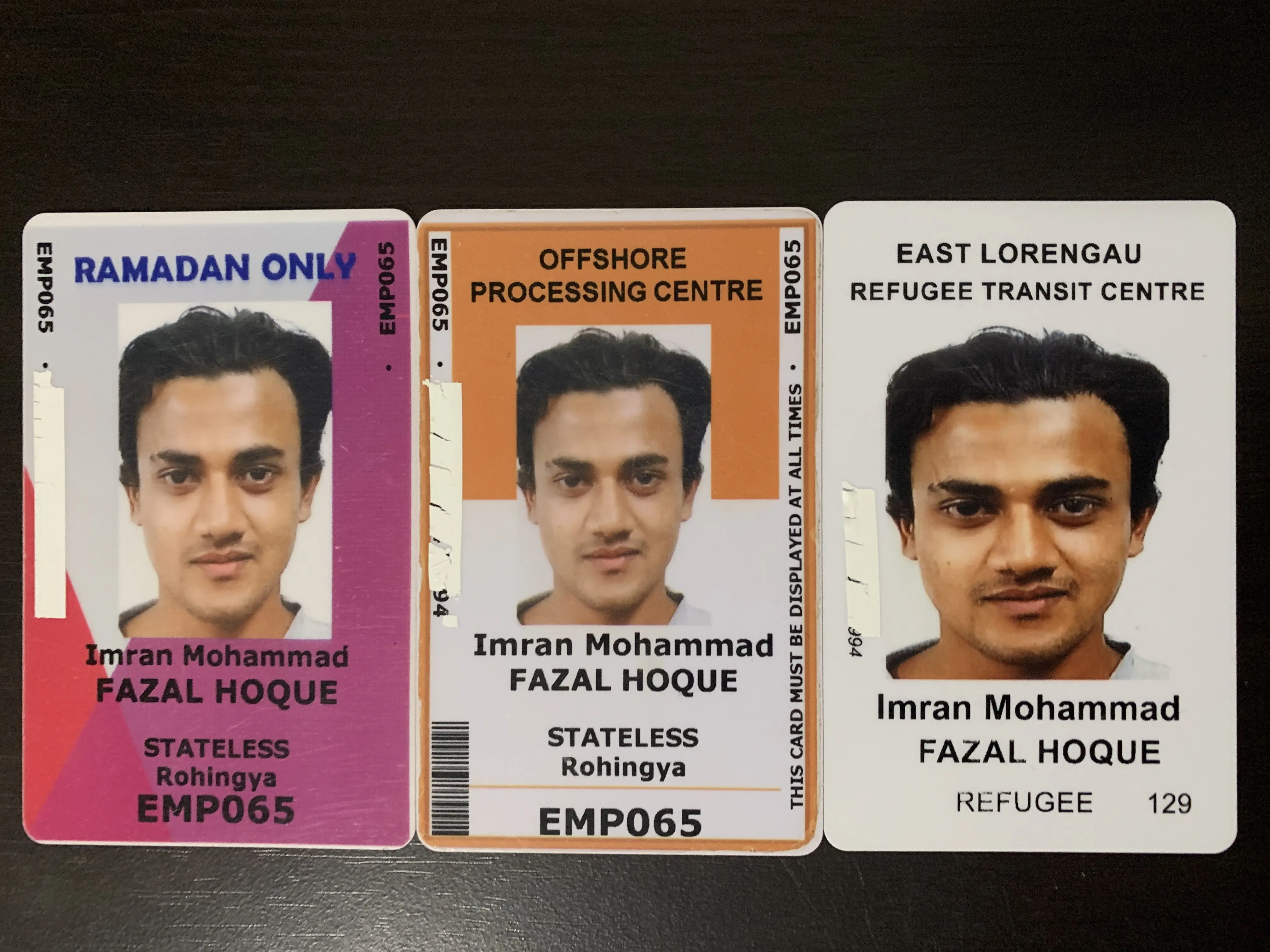

I didn’t know Australia had changed its immigration policy, so on October 29, 2013, I was transferred to Australia's offshore camp on Manus Island, Papua New Guinea. I had faith that Australia would treat me as a human being. Instead, they took away my name—I became EMP-065, my boat ID.

Life on Manus felt like psychological warfare. The outside world will not comprehend this prison unless they live there for some time. We were surrounded by security guards watching our every move. They knew our names, but we were called by our numbers. We were treated like animals. No books were allowed, but cigarettes were supplied; staff lost their jobs as a result of bringing reading material to refugees. The thoughts stir too many emotions as all these frustrations became torture when lived day after day.

I felt that it was the end for me, and my body didn’t feel pain anymore. I was like driftwood that gets lashed by tides. In a way, the utter cruelty of this modern prison was very interesting because I noticed that it would destroy the inner nature of a human life systematically, both psychologically, and emotionally. I saw how everyone’s behavior was altered in just a couple of weeks. The very nature of the environment was effective in crushing everyone’s hope, and we had no clue of our future and the world beyond the fence. I sensed them but I didn’t have words for them.

It was like someone was kicking me in my stomach, but I couldn’t scream for help. I would sit at a corner by the fence under a coconut tree and look at the infinite water. I was so close to the water, and it felt the tides would just wash all over me, but I couldn’t touch them. I had these painful psychological pictures playing in my head, but no one could see them except me. As a detainee, I realized it was only me who could bring them to reality for the world to see.

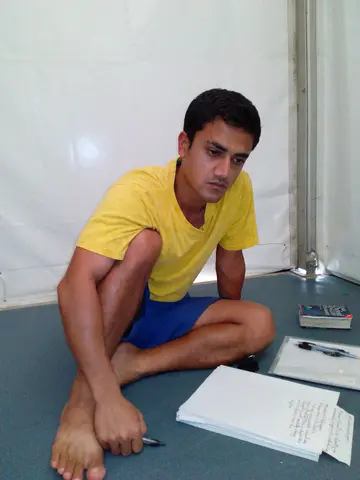

My imagination entered into an unknown world and I slowly learned to give a picture to my emotions and feelings. It all began with scratch papers from the floor or garbage bin and a pencil. One day I started writing while I was teaching myself English. My imagination allowed me to convey complicated abstract concepts in an infinite number of possible ways. I thought all day and all night long. At times, I forgot to eat and wrote for 16 hours.

Without knowing where I was going, I lost myself in a stream of words as I linked one after another. I escaped the cruelties through the sound of pencils scratching on paper. I walked on the ocean, touched the water, and gave myself a tour to a different island every day. I came back to reality every night so I could continue my journey the next day. It gave me hope and a purpose when I woke every morning.

Every event of Manus prison became art to me; they helped me to form words, and words combined to form sentences. I captured them in my universe of art.

Over time my one hand-written scratched page became eleven hundred, organized into twenty-one chapters. As I boarded the plane from Manus to Port Moresby in November 2017, I carried my life story with me, both mentally and in my bag-full of papers.

I taught myself English, and I emerged as a writer; my heart had found its love. I was surrounded by Australia’s cruelty but I survived.

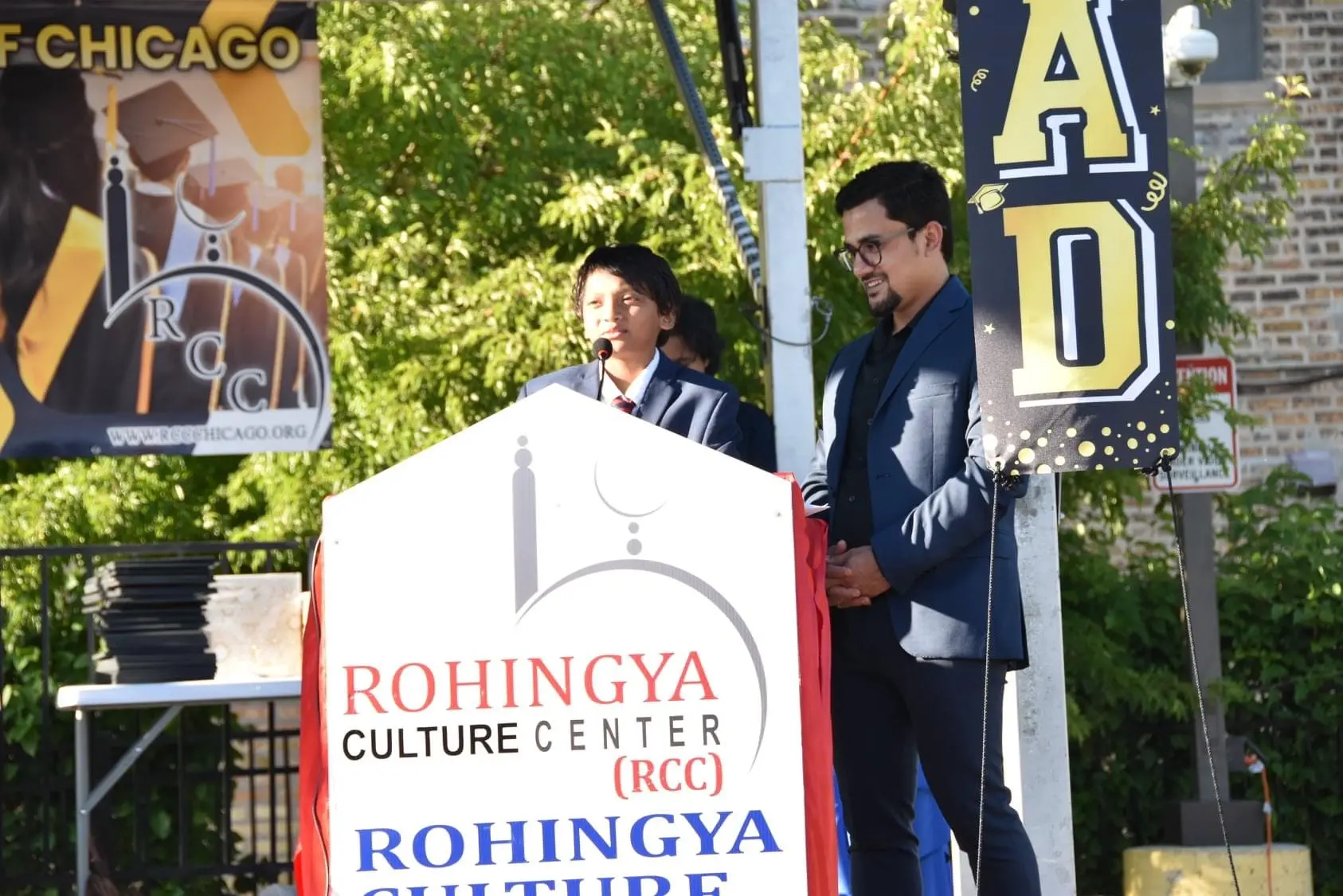

I arrived in the United States as a refugee in June 2018, and today I live in Chicago. My life entered a new era; it has been overwhelming, scary, and eye-opening. I didn’t know how I would make sense of being free in a new country with its society, customs, system, and language. I felt extremely lucky to have a good grasp of speaking and writing English. I see people so often in my Rohingya community in Chicago holding a piece of paper crying as they can’t read and understand it. Learning English for many is just beyond their capacity as we don't have a written language. I thought there would be fewer challenges in life after seven years of detention, but so many new challenges emerge with my new environment.

I gained my high school equivalency diploma in nine months and became the first person in my family to attend school, graduate from high school, and become a college student. It hasn't been a smooth journey, and COVID-19 has robbed more than a year from me. Going to college was the highlight of my day, but my world is just a corner of my small apartment and a desk now.

It feels bizarre to see how goal-oriented people are here in the U.S. because people in my Rohingya culture socialize a lot. A simple thing is an occasion. For example, a visit to the barber for a haircut can take a long time as we spend ages gossiping and drinking tea. It takes only 10 minutes to have a haircut here.

Because of my study commitments, I have to refuse invitations from my Rohingya friends and families, which is upsetting. I know it is going to be an extremely tough road, and it will further isolate me from the world I am familiar with.

While laws, policy, and decision-making processes fascinate me and take all of my attention, deep in my heart I will always be the Rohingya who learned to eat with his hands and the caring person that my parents taught me to be.

I strongly believe that I have to go down this road to understand the complexity, destruction, manipulation, policies, and laws that seem to orbit politics.

I want to acquire knowledge to comprehend why I was put through the hardships I endured, which were so unnecessary. I already have first-hand experiences of being stateless, an asylum seeker, and a refugee. Knowing what it is like to not be a citizen of a country, once educated I can be a force to destroy the stigma that revolves around these definitions, and I may prevent the tragedies that millions of refugees are facing around the world.

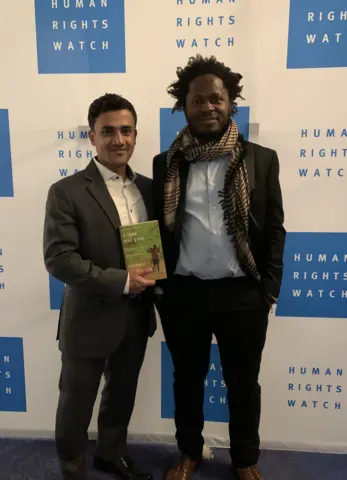

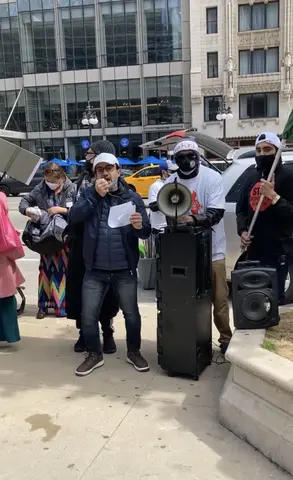

It is important for people like me to keep writing about injustices. I am deeply involved in writing and speaking to create an awareness of refugees’ lives, here and in other places where people are suffering in silence.

No one takes a journey on foot across the desert for fun. No one gets on a boat knowing the chance of death is certain, just for fun.