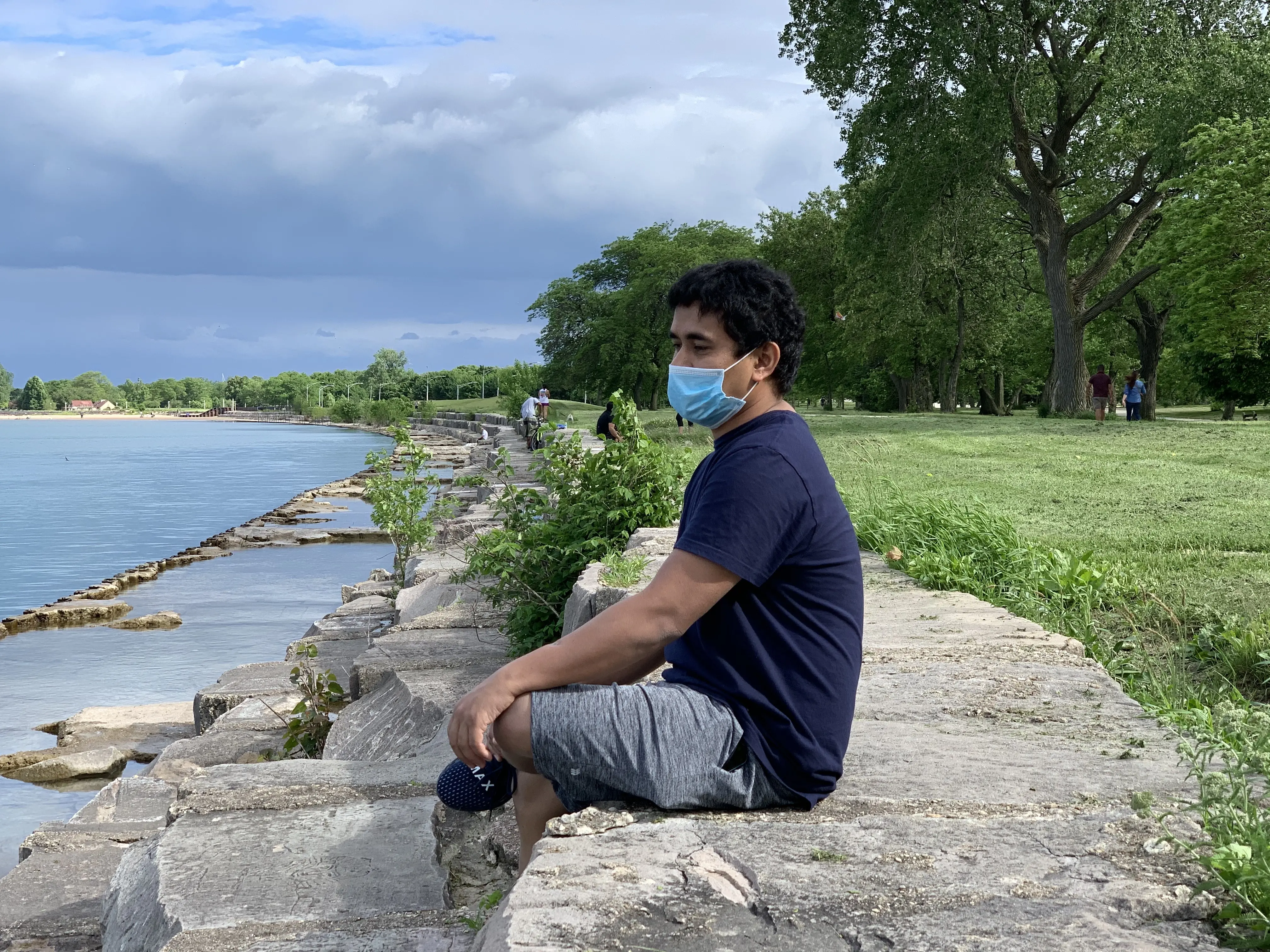

Mohammad Faisal, a 27-year-old Rohingya from Sobaran, Rakhine State, Myanmar (known as Burma until 1989), now lives in Chicago, where he greets people with his devilish sense of humor.

The persecution of the Rohingya in Myanmar led many refugees to settle in Chicago. One of the largest Rohingya refugee communities calls Chicago home where around 2,000 Rohingya are trying to build a sense of community on the North Side of the city.

“I don’t know how to talk straight and the reason could be that I didn’t have anyone to teach me how to comprehend different settings,” Faisal said while we sat safely enjoying sweet milky tea at a Pakistani restaurant on a Saturday morning.

Many traumatic stories hide behind his innocent face. Faisal’s mother died when he was only five years old. His young life was difficult as he grew up without her love. The youngest of eight children, Faisal felt the gap left by his mother’s passing most of all, and he spent time carrying out chores and caring for his frail, elderly father until his death when Faisal was 10.

Rohingya people have suffered significantly from decades of systemic torture by the Myanmar military because of their ethnicity and religion. Rohingya became illegal immigrants in their own motherland as the 1982 Citizenship Law ripped their citizenship away. They were made stateless and have been denied freedom of movement, access to social services, and education. There is no legal framework to protect Rohingya and, as a result, they have been subjected to violence, land confiscation, rape, torture, and large-scale forced labor for decades.

Faisal was cared for by two unwed sisters who remained at home, as other siblings had their own families to look after. Later, he was forced to move between his brothers’ houses where he worked their fields and rice paddies and grew vegetables.

“Life has never given me a chance to complain about something. I wish I could say no to something once in my life and get what I want, like my friends.”

Following altercations with Nasaka, the border security force, which became extremely unbearable, a teenage Faisal feared for his safety. “The officers would call me [a derogatory term for Rohingya Muslims]," Faisal explained. "It was like they were stabbing on my chest, again and again.”

He would not work at the military bases and knew that meant jail, so in 2012, at the age of 20, Faisal escaped Myanmar. He fled on foot and by sea.

Faisal described his many boat journeys in Myanmar, Bangladesh, Malaysia, Indonesia, and Australia: “There was no time to think, choose, or make a decision. Things happened and I had to accept them. I completely trusted a piece of wood with my life to bring an end to my statelessness. The darkness at night and the waves killed me every night and all I asked my God during the daylight was to see a shore.”

Finally, in Indonesia, a small fishing boat was arranged so that Faisal could travel to Australia, where he was told he could have a bright future. The boat was about to sink when it was found by the Australian Navy and the almost 200 passengers were transferred to Christmas Island on September 14, 2013. Australia had changed its refugee policy: Those arriving by boat after 19 July 2013 would be transferred to Australia’s offshore detention centers on Manus Island, Papua New Guinea, or the island of Nauru.

Faisal was detained for 5 years on Manus Island. “I forgot who I was because my boat number—EMP 152—became my name,” he said. “I sensed once again my life would experience a different type of struggle and I would be stuck in a cage like I was in my country. I could escape Myanmar’s persecution but Australia’s torturous offshore prison on Manus crushed me completely,” Faisal said.

Transferred to the U.S. in June 2018 through the swap deal made between Australia and the Obama Administration in 2016, Faisal found his new home in Chicago. “I feel like a human, my life has a meaning, and I can go out whenever I want without having any fear,” he told me. “I know I won’t be chased by police and for the first time in my life I can proudly say I am a Rohingya from Myanmar.”

The U.S. has brought a permanent solution to his statelessness but also overwhelming challenges with its different culture, legal system, tradition, and language. “I felt like a ghost when people talked to me in English and I didn’t understand a bloody single thing,” he said.

That the Rohingya language is not written creates several problems. Faisal doesn’t have a support language to learn English—this restricts employment choices and hinders his advancement in the US. “I still panic when I receive a letter in the mailbox because I can barely understand it,” Faisal said.

The requirement to become self-sufficient within three months of arrival led Faisal to find employment in a glass factory. Next he worked at O'Hare International Airport at night as a cleaner and, after only three hours sleep, took a hotel hospitality class. He was hired by the Peninsula, a Five Star hotel in Chicago. Faisal, like hundreds of other refugees, never had the opportunity to process and heal from the trauma he had experienced.

It was a nightmare when Faisal later lost his job because of Covid, as he didn’t have the language skills to apply for unemployment benefits, especially virtually. To add to his worries, he explained “I had constant calls from back home asking for support. Their situation doesn’t allow them to comprehend the past and current trauma I experience,” he said.

For many young refugees life is very straightforward: Go to work in the factories and come home to sleep, a cycle only a few manage to break. Faisal hopes, “I wish I had a day to think and, breathe and, the opportunity to take some extensive English classes, to play a game, or to understand the society and the system I am living in.”

Faisal took a breath and said, “Gaining the title of a good man in the community means I have to hold on to my culture, tradition, and belief system. There is no discussion about love, feelings, emotions, and sex before marriage.”

He loves meeting people and longs for human connections. His community is his only comfort, but many of them suffer socially, because of their lack of English. In general, the population forgets that young Rohingya men like Faisal need emotional support.

“I want to have someone to love and a family but you know there is a shortage of Rohingya brides. The few who have grown up here want to marry a man who was born in Malaysia or is growing up in the U.S.,” Faisal said. There is a tendency among the young Rohingya girls to believe the men who were born in Rakhine State won’t understand them. Also, Rohingya men can’t manage to save at least $20,000 from their low-paid jobs as dowry to marry a Rohingya girl.

For emotional support, hundreds of young men turn to Rohingya girls in Bangladesh camps or in other parts of the world where they remain stateless. “I am not stateless but statelessness will follow me through my family, relatives, and others,” Faisal said.

To comprehend Faisal’s feeling of loneliness and resilience to lay aside the trauma he has suffered in order to move on and to support family back home, I followed him to his current job.

Despite the massive trauma he has experienced and life’s ups and downs, Faisal feels proud and blessed to have gained his commercial driver's license. He didn’t think he could ever read the material he received via email about the CDL course, respond, and pass the exams successfully. He said, “A Rohingya friend of mine mentored me and I wouldn’t be where I am today without his help. I am very fortunate to have a mentor like him.”

Speaking as an interstate truck driver, Faisal says, “It is scary to be on the road for weeks.” He misses praying in the mosque and finding Halal food is very difficult. He wishes he had a Rohingya truck driver friend to talk to.

Faisal told me, “The frightening part of my job is if something happens, no one will come looking for me as I don’t have any family here.”

“I guess my God will forgive me for not being able to practice my daily prayers as my work is delivering essential goods to people’s homes. This is something that I can do for the country that offered me a new life,” he explained. “My days are meaningful. I will continue to work hard and be a proud citizen of my new country,” he said.

Faisal wept as he concluded, “It is easy to break a piece of glass, but it can never be put back together as it was before.”