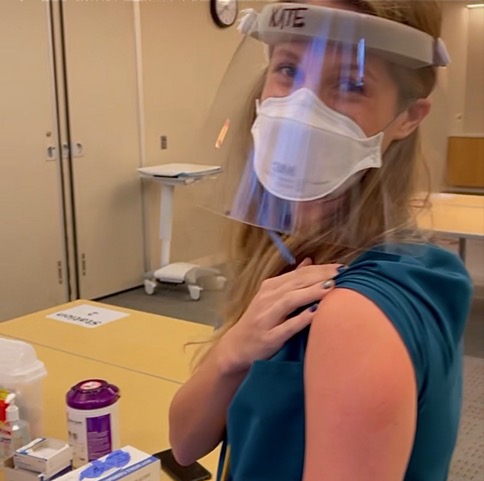

Kate*, a psychiatric nurse at an inpatient mental health facility near New York City, discusses her experience receiving the Pfizer vaccine in December, touching on vaccine hesitancy among her colleagues and the mental health crisis exacerbated by COVID-19.

She warns the impacts of the pandemic will be felt for

generations to come.

This interview was conducted in December 2020. It was condensed and edited for clarity by Kelly Cannon.

Q: Talk to me about your experience getting the COVID-19 vaccine today and how you’re feeling now.

A: It was much more of an

emotional experience for me than a physical one.

It was a quick pinch and didn't

feel any different than a flu vaccine. As for side effects, adverse effects, I

had none. I felt totally myself all day, so nothing to report to that end. But

emotionally, I was definitely overcome and overwhelmed with hope and relief. It

was a really powerful moment.

Q: Who was your first call

after receiving the vaccine?

A: I called my last living grandma, my Omap, in Florida. She was the first one who popped into my head. I think that living alone in isolation as a senior citizen with no spouse, no children, no job, nowhere to go and anywhere that she would typically go is shut down—it’s incredibly depressing. I needed to give her that hope because she sits worrying about her family, about her granddaughter who goes to work every day but also worried about herself—will I ever get the vaccine, she's thinking. Knowing now that people in her family in real life are getting it means that she's that much closer to it herself, and so that was a really beautiful moment for me.

Q: Tell us a little bit more

about the patients that you work with every day.

A: I am a nurse in an inpatient psychiatric hospital. It is an acute stabilization center for mostly psychotic patients. We often talk about mental health and the importance of mental health and how gravely misunderstood psychiatric illnesses and mental illnesses are by our healthcare system, but when we have that conversation, what we're failing to do is also address there's a very sizable piece of that population that is acutely psychotic, drug-addicted, homeless, schizophrenic, bipolar-manic. These people cannot help themselves. Added to that are comorbidities my patients suffer from like diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and poverty. These are my patients. When I'm not treating the adult population, I'm on the kids unit, and my kids check a lot of the same boxes as my adults. The kids come from foster homes, they get shuffled around, and they end up at our hospital because of the mental health crisis or behavioral crisis that gets them sent to us.

Q: How has COVID-19 affected that?

A: In the beginning of the pandemic, we were unsure of who had COVID when they walked in the door. There was no reliable testing. There was no reliable PPE. Even though testing became a little more reliable throughout the summer, we still didn’t really know if a patient had COVID. As our patients began to come in from other hospitals, they would have a negative COVID test and we would retest them five days after admission.

When you take a patient who tests negative upon admission and retest them on day five and they test positive, what do you do? Do you kick them out of this mental health hospital? Do you keep them in? Do you isolate them? These are questions that our management and administrators were grappling with all year. This has become a huge issue for us as the numbers are continuing to rise again. We don't know what to do with these patients.

Q: What is the media missing in its coverage of COVID-19 in the U.S healthcare system? What are we not seeing and talking about that’s affecting providers like you?

A: We talk a lot about mental health now. This has become a real hot button topic that we're not discussing mental health, and one thing that has always irked me is that we have that conversation in somewhat of a privileged echo chamber that we need to give ourselves a break. Anxiety, depression, maybe bipolar depressive disorder, all these issues that we could face as functioning adults in society. We need to look at the people who are literally mentally disabled due to their mental illness and cannot care for themselves, not to mention they live in group homes and shelters or in jail. They are 10 times more at risk of contracting COVID and because they have comorbidities, they're 10 times more at risk of having a really awful case of COVID. So, that’s one way of looking at this that I firmly believe has been overlooked by mainstream media and in our culture overall with respect to COVID.

Q: Are mental health and

psychiatric inpatient clinics designed for the type of isolation required to

house patients in this pandemic right now?

A: These facilities were not designed to have patients under isolation—both out of protection for that patient, the other patients, and the staff. When you have a person who's experiencing a mental health crisis, they require mental health treatment, they require the therapeutics of group therapy, one-to-one therapy, pharmacological therapy among others. All of these components of what makes up a psychiatric hospitalization they cannot receive because they are positive for COVID. Psychiatric hospitals are designed very deliberately to mitigate any self-harm risks to self or others. The layouts of the rooms, the doorknobs, negative air pressure rooms in ICUs—everything is not constructed for medical grade isolation.

Not to mention, when we do isolate the patient? In a typical hospital setting, the patient would at least have a television in their room and amenities that they could enjoy, distract themselves with. Psychiatric hospitals do not have that. What ends up happening is we have makeshift isolation hallways where patients are kept behind closed doors. Nurses and mental health workers come in to cluster their care and do things in one quick go—dressed in full hazmat suits. We go in and we get out.

It’s a really sad and

unfortunate reality for these people that they come in looking for help and we

end up isolating them. Our hands are tied behind our backs because we have no

choice. We're not serving these people right now. But they need to be in our

hospital because they are unsafe to themselves or others.

Q: What’s the alternative if your

patients are not in your hospital? Where do most of these people go?

A: The streets. They will not be allowed in their group homes if they're experiencing a psychotic or schizoaffective episode or manic episode where they're disruptive to their home situation. They will not be allowed in a shelter from the community because they have a positive COVID test. So where do they go? They go to the streets. So we're keeping them safe from the street, but we're not treating their mental illness and we're not treating their COVID.

Q: How is that affecting the

morale and your day-to-day feelings about doing your job?

A: It’s challenging. It’s a

push-pull of our ethics. Like I just said, what’s the alternative?

Q: How do you think the vaccine

has changed morale? Has it potentially changed behaviors within the

organization?

A: It's interesting, I think my

expectations of my colleagues were that we would all be fighting for our spot

in line, but the reality is there is a lot of doubt. There is a lot of question.

I encounter a lot of my very esteemed and respected teammates who read

something on Facebook or Instagram and they run with it.

Q: Is the hesitancy seeping into healthcare providers? I wonder what the solution is. Is your employer requiring staff to get the vaccine?

A: No. It’s not mandated.

Currently, it is voluntary.

Q: As a nurse who is in a

hospital and floating between different units, what are your personal thoughts

on employers like hospitals mandating that their employees get the vaccine in

order to be able to come to work.

A: I believe, much like I do with the flu vaccine, that when you are working in a position where your job is to provide safe, therapeutic care for people who are more vulnerable and cannot help themselves, it is our ethical obligation to follow the guidelines that are prescribed to us by the leading bodies in our field. If the CDC and if all the public health officials were to agree that this vaccine was necessary to keep the public safe and to keep our patients safe in vulnerable positions, my feeling is that we are ethically obliged to do so. Now, I do enjoy an interesting conversation with someone who disagrees with me and I can see how they think that way. It's just not my personal opinion.

Q: What can we do to help going forward? Whether it's changing the narrative, directing resources or funds, what's the most important thing the public can do for you?

A: Both. A lot of redirecting the funds because what is happening to these people on the outside is a cycle and we ended up having frequent fliers who leave and come back. Currently, due to the pandemic, what we need are more stable and committed outpatient programs that can function during COVID. Because we do not have the capacity to admit every homeless, or drug-addicted or psychotic person from the streets. We just frankly do not and we cannot. So these individuals need to have access to outpatient care consistently, caseworkers who are consistently following up with them, visiting nurses who are consistently keeping these people accountable to stay on track with their meds. What's happened in my hospital is that we've become a holding facility because of where these people go next—we don't discharge them home to their house with the white picket fence. We discharge them to the less acute center and then they get discharged from there to the residential or the group home. There’s so many layers and we can’t get to the next layer because the beds are full and there’s nowhere to go. We are suffering from a housing shortage for people who struggle from these issues.

These cycles need to break. We

need to fix what's happening outside of the hospital, so that when we're in the

hospital we can focus on our job and not just finding them a home.

I don’t know how we’re going to get out of this. And I think that the mental health part of our health system will be picking up the pieces of this pandemic long after the ICU beds are empty. The ICU beds will slowly empty, the EDs will slowly come back to normal. But not ours. Not the psychiatric centers. And we will feel the reverberating effects of this pandemic for years and generations to come.

*Kate's last name is withheld to protect her privacy.