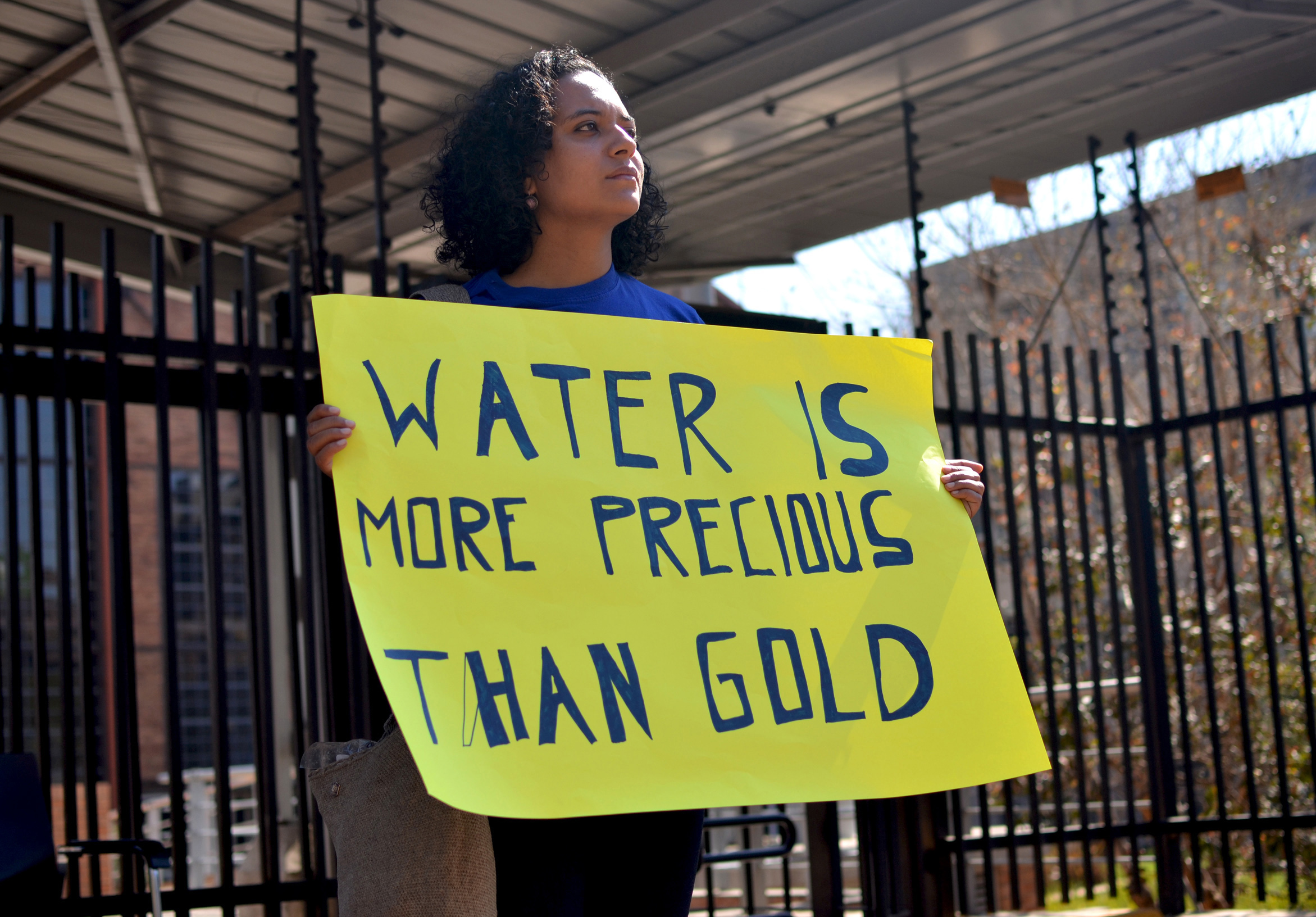

Symbolic at best, the tiny group of protesters stood outside AngloGold Ashanti's headquarters in Newtown, Johannesburg, in September. Secure behind a high gate, company employees could neither see nor hear the protesters who had travelled from Colombia.

A coalition of farmers, activists and scientists, they were leading a groundswell of opposition against a gold mine proposed by AngloGold in Colombia. Several people had been killed since protesting began, but the company claimed the deaths had nothing to do with their activism nor with AngloGold.

The community recently voted against allowing mining in the area, an ecologically-sensitive mountain forest, and AngloGold decided to "pause much of the current fieldwork," said company spokesperson Chris Nthite.

"(Mining) threatens our systems of water and food production. We don't think this is the right choice for our land. We prefer to live with water and agriculture, not mining," said activist Ximena Gonzalez.

While AngloGold is no longer part of the Anglo American (Anglo) group, it was born out of the South African mining empire, which now has offshoots around the world. At its centennial mark of operations, Anglo holds a mixed legacy, having benefited from unfair labour practices while acting, at times, as a progressive industry leader.

Now, in the face of shifting minerals needs and organised opposition, the legacy of Anglo is in many ways tied more closely to closed mines than those still operating.

Anglo was founded by Ernest Oppenheimer in 1917, and in 1929 he became the chairman of De Beers, by then controlled by Anglo. He forged on, building one of the world's dominant mining houses.

In 1946, the Geduld No. 1 borehole near Welkom struck significant gold. While mining had already been under way, this set off a gold rush in the Free State goldfields.

Two years later, D Jacobsson, at the time The Star's mining editor, described "Johannesburg's orgy of speculation" in his book Maize Turns to Gold. Even at the time, the rush added about £30 million to the JSE nearly overnight.

In a question that could not have predicted the current abandonment of South Africa's mines, Jacobsson asked: "Will the Free State goldfield set up any challenge to the prestige of the Blyvooruitzicht mine of the Far West Rand, the world's richest property in large scale production?"

Blyvooruitzicht Gold Mine, which began operations in 1937, was abandoned in 2012 by DRDGOLD and Village Main Reef after a sale soured. It is now a poster child for the problems engrained in a contracting gold industry that failed to properly plan for environmental and social rehabilitation.

Of course, the spectacular rise of the gold industry in South Africa came on the backs of Africans trapped in a system of migrant labour that upheld apartheid. While Anglo was progressive in opposing some apartheid practices and implementing programmes such as employee HIV testing, it greatly benefited from cheap labour and state subsidies the system provided.

Harry Oppenheimer gave a speech in New York in 1984, for example, arguing for all races to receive political representation. At the same time, he argued against economic sanctions, said "homelands" were too entrenched to abandon and called those living in political exile "the worst possible guides in such matters".

Welkom, with Anglo as its most important player, was designed to be a South African utopia in the midst of pre-apartheid racial tensions. Everything from health (the town came with a state-of-the-art hospital) to traffic patterns (traffic circles replaced robots at major intersections) was planned to make life easy.

Kobus de Jager is a mining researcher who spent decades working in the Free State goldfield and was an executive at Freegold, one of Anglo's major subsidiaries that controlled many of the area's mines. He said Anglo did its best to treat all its employees well, but that there was far too little planning for how the hundreds of thousands of people directly and indirectly dependent on mining would survive when Anglo left.

"(Planning) was left too late. By then, you didn't create an alternative industry within Welkom for it to actually survive in the long term. What happened is you created poverty traps," he said.

Pule Ledoka Gubico, an activist associated with the Bench Marks Foundation, surveyed the massive piles of mine waste running along the side of the road and the abandoned mine shaft rising from the rubble of a partially demolished gold mine. He had spent the day testing water quality around the Welkom area, and this particular barren landscape caught his eye.

"This is what's left by the mining companies. They have taken everything else," he said.

This, said De Jager, is in part because environmental consciousness did not permeate the Anglo group until the 1990s. He claimed that the mere demolition of a site was accepted as environmental rehabilitation for many years.

Research published in 1903 had already identified acid mine drainage and the industry's understanding that its pumping of underground water could lead to the problem. Because of this knowledge, some activists claim Anglo could face charges of fraud internationally for historic environmental damage caused by its subsidiaries.

Anglo denied that any grounds exist for such a charge.

"Anglo American was quite clever to pull out of these (mines) because the legacy and latency of occupation hygiene issues such as dust was starting to simmer at the time," De Jager said, alluding to diseases such as silicosis. "Instead of preserving the environment for future generations, they actually allowed it to be stuffed up."

As happened with gold, South African coal is now becoming a less attractive place to invest. International markets are lost to the renewable electricity generation, coal prices have dropped and Eskom is pushing policies that major mining houses find difficult to meet.

In May, 2015, BHP Billiton cemented its exit from South African coal when it demerged with South32.

Anglo followed suit and announced in April that it would sell its Eskom-tied coal mines to Seriti Resources Holdings. The sale includes three operational and four closed mines.

Anglo representatives say the company transfers its financial provisions for rehabilitation to buyers in sales of mines, even though this is not legally mandated.

"We would never knowingly dispose of any of our rights to an entity that was either unwilling or unable to assume responsibility for any of the obligations attached to those mining rights," said Anglo spokesperson Ann Farndell.

The Centre for Environmental Rights sent Anglo a letter in April asking for transparency and public participation in the selling of these mines to ensure that environmental obligations are met.

In a press release on the matter, the NGO explained that the letter was a response to "the growing trend in South Africa where large mining companies, often with major environmental liabilities, sell their mines to smaller mining companies.

"These smaller companies are often either unwilling or unable to fulfil the rehabilitation obligations imposed by the mining rights for these operations. When environmental liabilities are abandoned, they become the responsibility of the state, and therefore the responsibility of South African taxpayers."

Mines in South Africa notoriously pass hands from larger companies down a chain of sales until scavenger companies - small miners with insufficient funds for rehabilitation and no long-term plans - simply abandon them. As a major player in the industry, Anglo has been responsible for the opening of many mines, but not the closing.

Richard Spoor is a human rights attorney involved in the silicosis class action lawsuit, which involves Anglo and numerous other mining houses. He said that as some large gold miners like Anglo began leaving the industry, they would sell their assets and wind up subsidiaries.

"There's nobody left to sue. This is standard practice in the gold mining industry," he explained.

Duncan Innes, a former sociology professor at the University of the Witwatersrand, wrote his seminal book on Anglo American, titled Anglo American and the Rise of Modern South Africa. In it, he lays out a complex web of 656 companies connected in the Anglo American Group as of 1976.

These companies were active in mining in 22 countries spanning the globe from South African gold to Zambian copper, from oil in Europe's North Sea to prospecting in Canada.

Experts argue that the Oppenheimer family and Anglo's leadership were able to maintain a tight grip over the empire while using minority shareholding as a shield against liability.

Spoor explained that an international legal precedent called "parent company liability" is beginning to put the heat on large miners that operated before current best practices were adopted.

"If the parent company has the expertise, is engaged in the same business as the subsidiary and knows what's happening at the subsidiary, and it gives it advice that the subsidiary follows, then the parent company has a duty of care," he said.

Education Resource

Meet the Journalist: Lisa Palmer

Many of Colombia's rural areas have experienced conflict over 52 years of civil war. Now scientists...