WEST DUNBARTONSHIRE, Scotland — In her 30s, fresh out of college with loans to pay off and her young son Spartacus Summers finally old enough for school, Natalie Muir was in a rush to get a job. Someone told her to drop into the Clydebank High School and check in at the office of a local agency called Working 4 U — which told her to just … slow … down.

That message came from Tricia McGovern, an officer at Working 4 U who would be the perfect aunt or sister. She knows all the angles, has all the connections, and fairly bursts with concern for others’ problems.

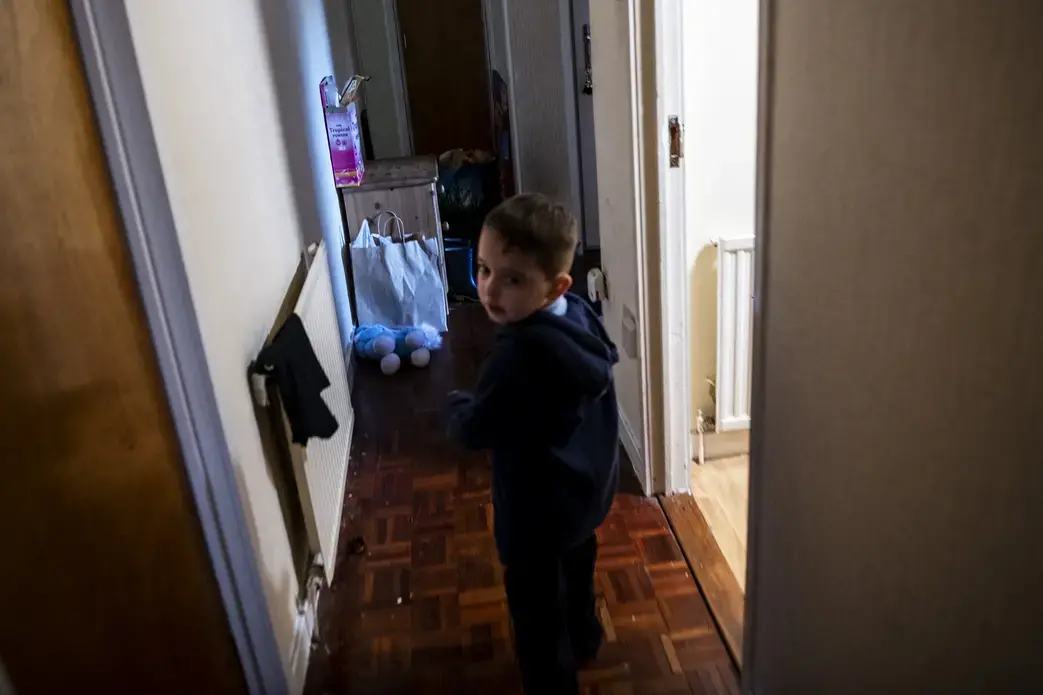

Ms. Muir “was quite rightly proud of her achievement, but there was a huge amount of uncertainty that rushed into her life,” said Ms. McGovern. She was the single parent to Spartacus and his sister Monique Summers, 16. So instead of rushing Ms. Muir into a job, Working 4 U helped her to sort through the benefits available to her — and introduced her to the local food bank.

Working 4 U operates in an area west of Glasgow, down the Clyde River, which has a history not unlike the Mon Valley’s.

Gone are the massive Singer Sewing Machine factory and the shipyards that once joined Glasgow’s in producing a big part of the world’s fleets. All that’s left of that now is a giant blue crane known as the Titan that casts its shadow over a massive private-public development site.

“The west of Scotland has for a long time been blighted by deindustrialization,” said Stephen Brooks, the Working 4 U Manager for West Dunbartonshire Council.

“Areas of Western Scotland became a wasteland,” and of the 90,000 residents of the district, some 35,000 live in neighborhoods that the Scots characterize as areas of “multiple deprivation” — low incomes, limited housing options, high crime — said Mr. Brooks.

Unlike much of the Mon Valley, though, West Dunbartonshire’s government didn’t fall off a fiscal cliff when industry left. That’s because Scottish local government doesn’t rely primarily on the local tax base. Around 85% of the cost of local government (including schools) is covered by allocations from the national government, with the rest covered by property taxes and fees.

In Pennsylvania, it’s basically the reverse. The commonwealth’s cities, boroughs and townships get, on average, 22% of their funding from the state, according to a 2017 analysis by the National League of Cities.

Ms. Muir, 34, didn’t want to go to the food bank. “We’re Scottish. We’re very proud, you know,” she explained. But cuts to public benefits, high rent and her student loan payments threatened to push her deep into poverty, and Ms. McGovern not only talked her into going, but drove the groceries to her door.

Now that Ms. Muir has the resources to meet her family’s needs, she’s working with Ms. McGovern on budgeting and setting up a vocational plan in line with her education in beauty therapy.

Under the Child Poverty (Scotland) Act, passed in 2017, local governments have to report annually on their efforts to increase employment and reduce household costs for families in poverty, with the aim of slashing child poverty to minimal levels by 2030.

Mr. Brooks proudly cites the 500 people Working 4 U put into jobs last year, but he also feels he’s rowing against the current.

“Over the next few years there’s going to be a 6% increase in the level of child poverty,” said Mr. Brooks, citing experts’ predictions. “That’s a direct result of the reduction of welfare, the changes in the welfare benefit system.” If the United Kingdom leaves the European Union, the headwinds could be even stronger, he said.

West Dunbartonshire is trying to ensure that any increase in poverty does not result in a spike in homelessness.

“We have a major house-building program underway, to what I would argue is a very high standard of design,” said Peter Barry, head of housing and employability for West Dunbartonshire Council. “We’re building houses so that effectively anybody, with any level of need, can live in the house.”

There are more than 10,500 public housing units in West Dunbartonshire, or roughly ¼ of all homes. Another 7,000 units are run by “social landlords” under a system roughly analogous to the Section 8 program in the U.S. Unlike the U.S., Scottish public housing can accept people of any income level, though the poor get priority.

“As a human being, we have an absolutely innate duty to look out for each other,” said Mr. Barry. “We believe there’s a profound moral, ethical duty to deliver services and to allow our children to flourish — to allow people to tackle problems that are not of their own making.”