Illegal nickel mining runs rampant in Sulawesi. It is the result of bad governance.

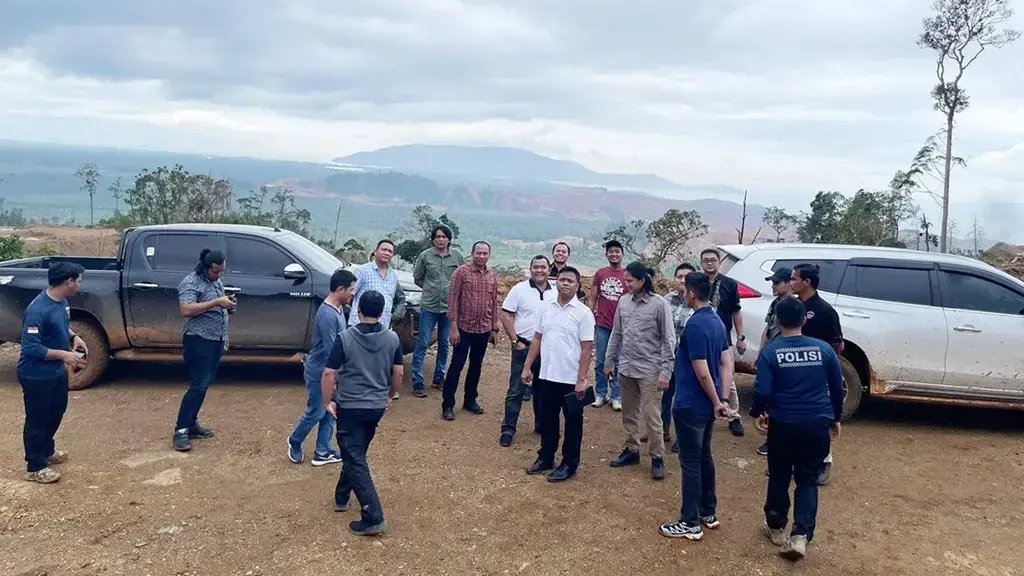

THREE days before the end of 2022, dozens of police officers from the Southeast Sulawesi Regional Police came to the Mandiodo Block. However, the 16,000-hectare-wide area was already deserted. The police did not find any illegal nickel miners they intended to arrest. “There was no longer any activity,” said the Sub-directorate IV Chief of Southeast Sulawesi Regional Police Special Crime Investigation Directorate, Comr. Ronald Arron Maramis, Friday, February 3.

From the hill that makes up the nickel center of Southeast Sulawesi in North Konawe, the police confiscated 300 tons of nickel that were ready to be shipped to port. The miners also left behind four units of heavy equipment. The police suspect that mining activities in this block are illegal because Aneka Tambang or Antam, the concession owner, has not obtained the forest area utilization permit (IPPKH).

The IPPKH is the final permit for a company to be able to mine natural resources in forest areas. An analysis of satellite imagery by Tempo and Greenpeace Indonesia reveals that the mining areas in the Mandiodo Block are mostly located within protected forests and limited production forests, and also have been included in the Cessation of New Permits Indicative Map since 2020. According to the police, nickel mining activities have been ongoing since 2019.

Whistleblowers and others in possession of sensitive information of public concern can now securely and confidentially share tips, documents, and data with the Pulitzer Center’s Rainforest Investigations Network (RIN), its editors, and journalists.

According to Ronald, there have been at least five raids against illegal mining in the Mandiodo Block since 2022, when Antam officially owned the block. Antam sued dozens of companies that also owned mining operation permits (IUP) of the block in 2011. After three years of court proceedings, the judge ruled in favor of Antam. The problem is that illegal nickel mining continues.

From all the illegal mining raids in the Mandiodo Block, the police have named three suspects and confiscated 19 units of heavy equipment as well as more than eight mounds of nickel ore. Referring to Law No. 3/2021 on mineral and coal mining, illegal miners could face punishment of five years in prison and a fine of Rp100 billion.

Throughout 2019 to 2022, illegal nickel mining in the Mandiodo Block covered an area of nearly 1,000 hectares wide. In 2022 alone, illegal nickel mining in this block reached 228.58 hectares. Meanwhile, Antam’s permit last year only allowed 42 hectares. Antam did not mine on its own. The state-owned enterprise cooperates with Lawu Agung Mining and a regional company of Southeast Sulawesi (see interview with the owner in this article).

The management of Antam has requested the police to take action against companies holding old IUPs that no longer have rights over the land in the concession area. “Antam wants to invest, so it must not be disturbed,” said the Specific Crime Director of the National Police Criminal Investigation Department Brig. Gen. Pipit Rismanto.

The miners admitted that their illegal activities are protected by law enforcement authorities. They are able to sell nickel all the way to smelters without issue because they pay a ‘coordination fee’ to authorities of US$16 per ton of sold nickel. One of the names of police officers being mentioned by the miners is Brig. Gen. Pipit Rismanto.

Pipit has another explanation. According to him, when Antam asked the police to act on illegal miners, he suggested the state firm get the villagers around the mine to work in the mining of nickel. The requirement being that the locals own mining operation permits and other legal documents. Antam agreed to Pipit’s suggestion. “So, I am the backing of the community, not illegal miners,” he said.

Pipit explained that illegal nickel mining is not a recent occurrence, but rather has been ongoing since 2014. Companies that were defeated in court by Antam continue their operations despite not having work and budget plans from the energy and mineral resources department and not providing post-mining reclamation guarantee.

Pipit threatens to drag the illegal miners to court if they fail to fulfill their obligations, from reclamation guarantee, land and building taxes, to environmental damage due to mining. “But first we offer restorative justice,” said Pipit, mentioning the ‘peaceful way’ of law enforcement that has been adopted as the police’s guideline since being led by Gen. Listyo Sigit Prabowo.

Owner of Karya Murni Sejati 27, one of the companies mining nickel in the Mandiodo Block, Audy K. Siddieq, said that the offer has been discussed by Antam’s management with 11 companies holding permits for the block. Only, he explained, the agreement did not mention specifics about payment obligations. “We have paid for reclamation guarantees as well as land and building taxes,” he said.

The illegal nickel mining mess in Sulawesi is rooted in regulations. As a new natural resource for raw material of batteries, nickel is sought after by many countries. During a discussion about nickel governance on Tuesday, January 24, held by Transparency International Indonesia, it was revealed that loopholes enabling nickel mining corruption were present before the government issues a mining permit.

Mining law expert from Tarumanegara University, Ahmad Redi, said that the chaos in nickel mining governance is exacerbated by weak law enforcement. The absence of a system capable of detecting the legality of the origin of nickel prior to being sold to smelters further fuels the practice of mining nickel without permit in Sulawesi, as Tempo’s investigation discovered.

The government’s partiality to large corporations is also a problem. According to Redi in some nickel-rich regions, the government prioritizes permits for corporations, instead of traditional miners. The traditional miners cannot compete with corporations when participating in tenders for mining operation permit areas (WIUP). “There should be more traditional mining permits, not WIUPs,” said Redi, who helped draft the Mineral and Coal Law and the Job Creation Law.