Hollis, Queens has been flooding for nearly a century. Current residents are living in fear whenever it rains. As climate change continues, other areas of New York City will also experience severe flooding.

Amit Shivprasad stood chest-deep in water, looking at the middle of his street in Hollis, Queens. Rain pelted him from above and the thought of electrocution from a downed power line flashed through his mind. He was looking for a whirlpool forming above a manhole, a sign the water was receding into the sewer. But that early September night in 2021, the night of Hurricane Ida, the manhole was gushing water like a fountain.

Regardless, with one hand above the water, he held his phone at eye level and continued recording. He was determined to capture the flooding that afflicted his neighborhood with every yearly storm. He wanted to show how dangerous rainfall could be.

By now, nearly 9:15 p.m., the water reached his chest. The water was pitch dark, except for the lampposts that shimmered on its glassy surface. A heavily built man at 5 feet, 10 inches tall, Amit was able to see leaves and trash floating all around his street. The water was beginning to cover his neighbor’s elevated front porch steps. Most homeowners stood at their front doors, peering at the flood that kept swelling on 183rd Street.

As a nonprofit journalism organization, we depend on your support to fund our nationwide Connected Coastlines climate reporting. Donate any amount today to become a Pulitzer Center Champion and receive exclusive benefits!

Amit and his parents, immigrants from Guyana, came to the United States in 1997. They purchased a two-story house in Hollis, a largely Guyanese neighborhood five years later. Earlier that night, his family began their routine preparations for a storm: check the Weather Channel, monitor the FEMA weather app, and venture outside in yellow ponchos to pry open the street’s manhole covers to let water drain faster.

When Amit and his father, Ragendra, left the house in their ponchos, Amit’s mother began alerting the neighbors on WhatsApp about the storm. It wasn’t long before Ragendra returned home while Amit chose to stay outside to record. Inside the house, Ragendra knocked on the door to their downstairs basement.

Since 2007, the Shivprasads had rented out their basement apartment to Dameshwar Ramskriet, his wife Pramatee and their two children. Amit had met Dameshwar when they both worked at a nearby grocery store. The family was looking for an apartment to rent and Dameshwar asked if the basement was available. Amit agreed to rent it to them. The Shivprasads had, after all, reinforced the walls on each side of the house after a previous flood to prevent further damage.

Knocking on their door that night, Ragendra told the Ramskriets to go upstairs in case of a flood. He recalled knocking right as the family was preparing for bed. After notifying them, he stepped outside and yelled at Amit.

Somewhere between 9:30 and 10:30 p.m., Amit’s mother, Ramrattie, was on the second floor of the house when she suddenly heard a thump coming from downstairs. The thought of a column falling in the basement came to her mind, she said, and she rushed downstairs, where she encountered Dameshwar standing in front of the basement door.

Dameshwar’s wife and son were trapped.

Ramrattie rushed to dial 911. The lines had been overwhelmed that night and she wasn’t getting through, so she called 311 instead.

“They kept asking so many questions, so I told them — ‘Listen there are people trapped, this is the address. Please send someone right away.’ ”

Amit had been outside recording when his mother heard the thumping sound. When he returned, he saw Dameshwar standing at the door. He asked him where his wife was and Dameshwar told him they were in the basement.

“What do you mean they are down there?” he recalled asking Dameshwar.

Amit rushed out the front door, waded through the water on the front porch, turned left, and made his way to the second door at the side of the house that led to the basement apartment. He turned the knob and in seconds, the door blasted open with so much force it took the hinges off the doorframe. “[The water] was just at one place until I opened it,” Amit recalled. “It had nowhere to go.”

Amit was no stranger to flooding. At least once a year, rainfall would overwhelm the sewer systems and water would gather in the streets and seep into homes, destroying family photos, appliances, and much more. Fed up with the situation, Amit began advocating for his neighborhood by meeting with city agencies and politicians to ask for help.

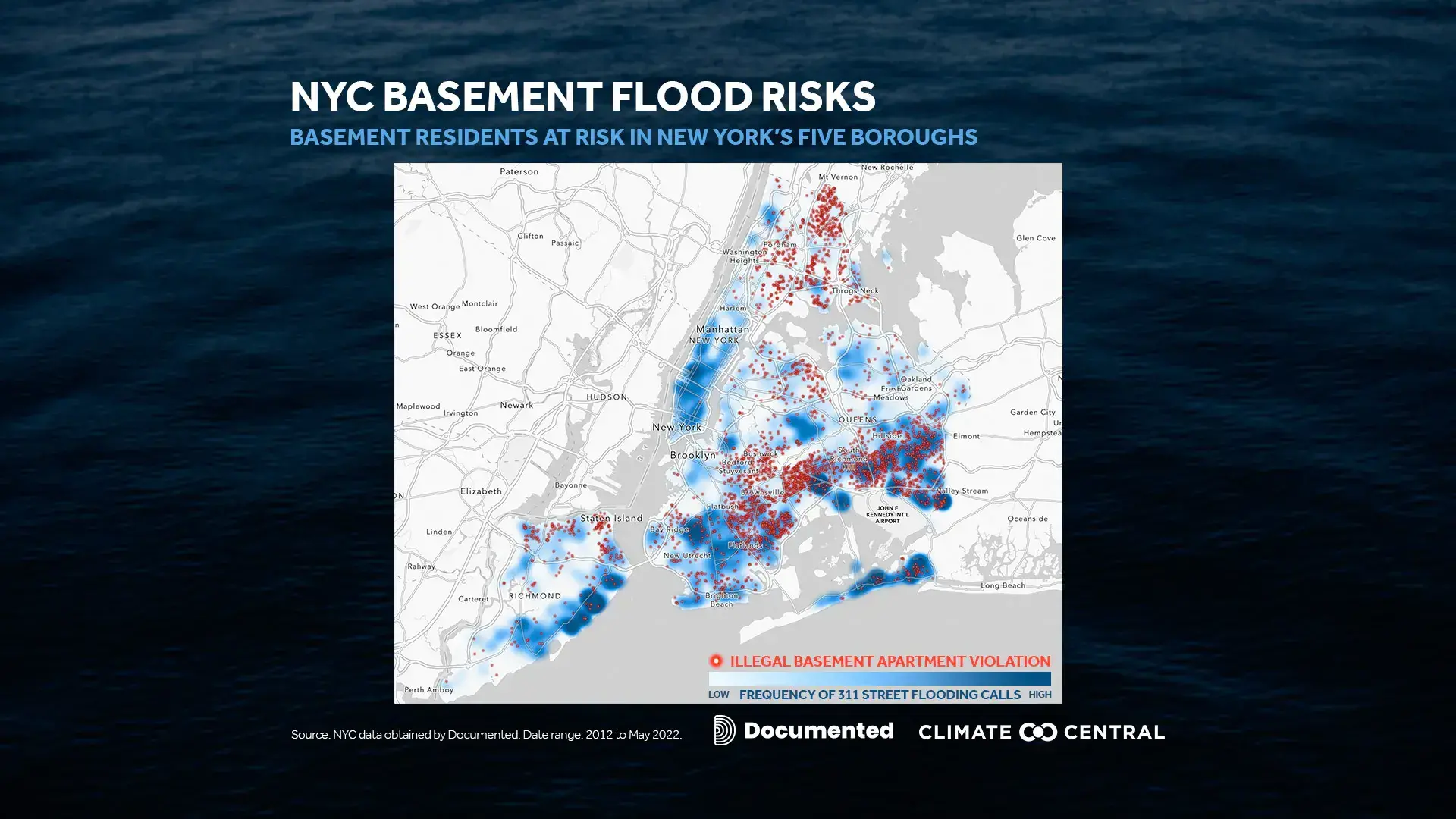

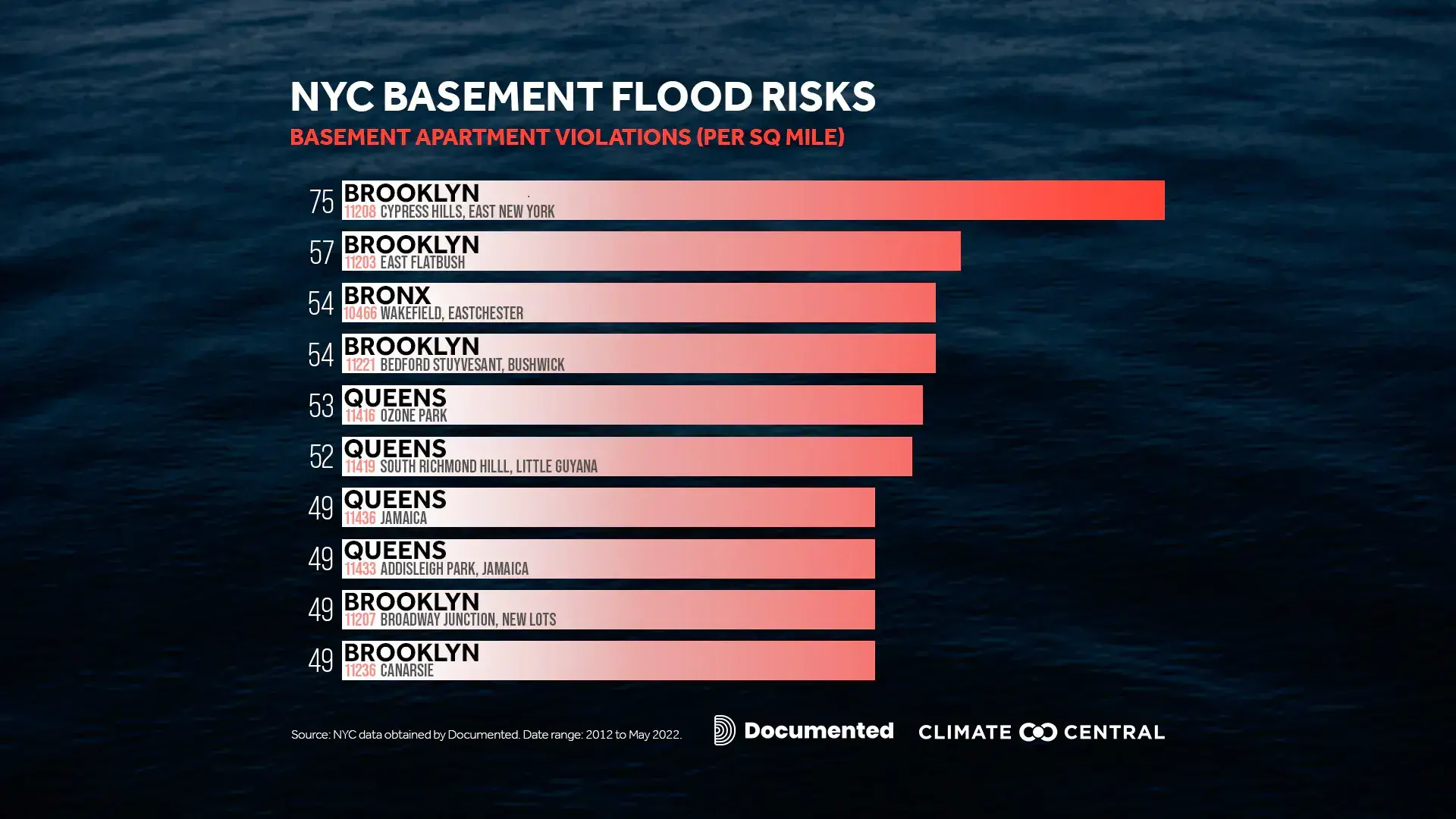

Rainfall has increased not simply on Amit’s block but across the world due to the effects of climate change. During the coming years and decades, intense rainfall will continue to become more frequent, worsening flood risks for communities most vulnerable to the effects of climate change. A data analysis by Documented and Climate Central shows that vulnerable basement apartments are clustered in areas at high risk of flooding. Those apartments are in parts of New York City where census data shows immigrants and people of color like the Shivprasads tend to live, particularly in parts of Queens, Brooklyn and the Bronx.

The residents of Amit’s block on 183rd Street, including Amit’s family, took precautions to deal with the repeated flooding on their street. They made costly alterations to their homes, kept track of storms to warn other residents, and as Amit and his father did every flood, placed their lives in danger as they ventured out during storms to ensure the sewers and catch basins were unobstructed. But on the night of Hurricane Ida, all of Amit’s efforts at avoiding tragedy washed away with the storm.

Rocky Beginnings

Some 20,000 years ago, Amit’s home in Queens stood near the southern edge of the Wisconsin Glacier, according to Eric Sanderson, vice president for Urban Conservation at the New York Botanical Garden. The glacier reshaped the terrain, leaving behind a body of water that came to be known as Rock Hollow Pond.

According to Sanderson’s reviews of historical documents, the pond disappeared sometime around 1906 when development in that area of Queens began to boom. While the pond itself was lost to history, its legacy remains in the form of a large dip where floodwaters quickly pool.

“People built houses on top of it, probably not knowing that there was previously a pond,” Sanderson said. “When it rains, water continues to follow the lines of former rivers and streams into the area, where it collects and pools.” The current streets slope down from Hillside Avenue to the intersection of 183rd Street and 90th Avenue, where the pond used to be.

Amit’s house was built in 1925, and evidence of flooding at the site dates back to the summer of 1928, according to a series of photos from the City’s Department of Records and Information Services. The Queens Borough President at the time, Bernard M. Patten, assigned a photographer to take the photos. Patten had considerable responsibility for monitoring infrastructure, and the photos show puddles of water in the empty lots of land where Amit’s neighbors now live.

Despite the floods in the area, development of new homes continued.

In 1990, the house in front of Amit’s home sat unoccupied for three years after the concrete foundation was found defective due to “flood-related damages,” according to Department of Buildings records requested by Documented.

When Amit’s family bought their current house in the spring of 2003, they appreciated the Hollis community, which was largely Guyanese, as it reminded them of their home country. For five years they had worked to save up to own a home. But when they bought their house and moved in by the end of the summer, no one warned them of the flooding, they said.

Six homeowners on the block who spoke with Documented, like Amrita “Amy” Bhagwandin, also said they were never told their house would be prone to flooding. But within months of purchasing her home, Bhagwandin, 52, who purchased her house in 2005, said water poured into her basement during a storm, trapping her in it. “I just hoped and prayed,” she said, adding that ever since that storm, she gets nervous and is unable to sleep during nights when it rains.

During that same storm, Amit’s home flooded for the first time. Water began building up behind the house and putting pressure against one of the windows in the basement. To stop it from entering the home, Amit placed his palms against the glass, and the pressure of the water pushed the window pane against him. He said he was sent flying across the basement apartment. “It was a hint of what the water could do.”

In the following months, his father used $16,000 from his savings to raise the porch and the entrance to the first floor so it stood 4 feet above the ground. After reinforcing the walls and raising the porch, Amit’s home stayed dry while other residents constantly got water in their basements, he said.

Like Amit, other homeowners on the block had taken similar measures. The house next door to Amit’s was altered five times between 1923 and 1968. Its main entrance now stands higher than Amit’s.

Sometime in 2007, Amit’s friend Dameshwar Ramskriet asked if he could rent the basement apartment for himself, his wife and two children. Because housing prices were high around the city, Amit rented it to them, saying he “wanted to help them out.”

Even though Amit’s home modifications kept the water out, he began to film and take photos of floods during major storms. His archive of photos, ranging from 2011 to 2021, shows brown water reaching levels above the tires of parked cars, covering one block, all the length of 90th Avenue to 91st Avenue.

Starting in 2010, Amit began meeting with elected officials, including former Mayor Bill de Blasio, Congressman Gregory W. Meeks (D-NY 5), City Councilmember Nantasha Williams, Public Advocate Jumaane Williams, and others. In 2019 Amit also made requests to meet with U.S. Rep. Alexandria Ocasio Cortez (D-NY 14) and U.S. Sen. Charles Schumer. He even sent a letter to President Biden in 2021, to which he received a generic response mentioning COVID-19, employment efforts, and health care, but nothing regarding the concerns Amit had expressed about the flood in his neighborhood.

“Everyone needs to come together, sit down and find a solution,” said Amit, referring to the many elected officials.

Extreme and Unpredictable

Climate Central analysts reviewed data from 150 rainfall gauges — instruments used to measure rainfall — across the country and found that the amount of water falling each hour on average has increased at nine out of ten locations since 1970.

While New York City’s rainfall gauge in Central Park shows a slight decrease in hourly rainfall intensity, Art DeGaetano, director of the Northeast Regional Climate Center at Cornell University, attributes this to chance.

“The rain gauge at Central Park has an 8-inch circle,” DeGaetano said. “If you broaden your view and look statewide, locally, regionally, or something like that, and pull together all of the different rain gauges that you might have — that‘s where it‘s really a lot more informative.”

DeGaetano led research published in 2021 that detected a 2.5% increase in extreme rainfall from 2000 through 2020 in New Jersey. “I have no reason to believe that New York City is going to be different,” he said.

His climate modeling suggests intense rainfall will increase nationwide by approximately 10% by the year 2050, compounding threats in areas that already experience flooding.

To combat the problems with flooding in blocks such as Amit’s, in November 2020 the City began changing and upgrading sewer infrastructure. The construction was part of the City’s extreme rain adaptation plan that had been put in place by the de Blasio administration five years earlier, with the goal of building up to 125 miles of new infrastructure.

It was a combined effort of city agencies — including the Department of Environmental Protection (DEP) and the Department of Design and Construction (DDC) — to upgrade sewer infrastructure and alleviate future flooding.

In Amit’s neighborhood, the City invested $10 million to replace the sewer and the water main between Jamaica and 90th Avenue. For this, Amit recalls the months before Hurricane Ida being loud. His home was shaking almost every day because of ongoing construction on the street.

The photo frames on the wall sometimes fell down and some of the walls on both floors had begun to crack, according to Amit’s parents. The DDC told Documented that they sent a Community Construction Liaison to notify the residents of the upcoming construction by knocking on doors, posting flyers and distributing information at the community board meetings. Amit said that, while no one had spoken to them about the project, flyers had been placed on the street about the construction. Amy, who lives across the street confirmed that flyers were dropped off and that emails were collected, where they received weekly updates via email.

Documented reached out to the DEP to ask about initiatives and construction done in neighborhoods affected by Ida. The agency’s spokesperson pointed to statements made by the mayor and other city agencies at the storm’s one-year anniversary.

The statement noted that extreme and unpredictable storms are no longer anomalies, and that for more than a century, catch basins and sewers have been the primary drainage tool across the city. As a response, agencies are implementing new management tools that would direct stormwater away from residences to mitigate future flood risks. Other initiatives include real-time notifications to alert residents if their area is likely to flood during a storm, as well as maps to show if an address is at risk of flooding during a storm.

But because rainfall rates during storms are uneven across small areas, warning residents in harm’s way can be especially difficult, said Bernice Rosenzweig, a professor of environmental science at Sarah Lawrence College, who said more data and science is required before localized rainfall rates can be accurately forecast.

“In terms of flood risks, it‘s not just where you‘re living in space on the x and y plane, but where you‘re living vertically,” said Rosenzweig, adding that fast-moving water can have enough momentum to sweep cars away before it pools in lower areas, where residents of basement apartments face the gravest risks.

It’s not known how many basement apartments are in the city because many are rented out and occupied illegally while frequently violating codes designed to protect against fire and floods. “Much of the population living in basement and cellar housing is there because they face other barriers to accessing housing and the housing market,” said Sylvia Morse, policy program manager at the nonprofit Pratt Center for Community Development.

The Pratt Center for Community Development estimated in a 2021 report that “thousands of New Yorkers, many working class immigrants and people of color” occupy such housing.

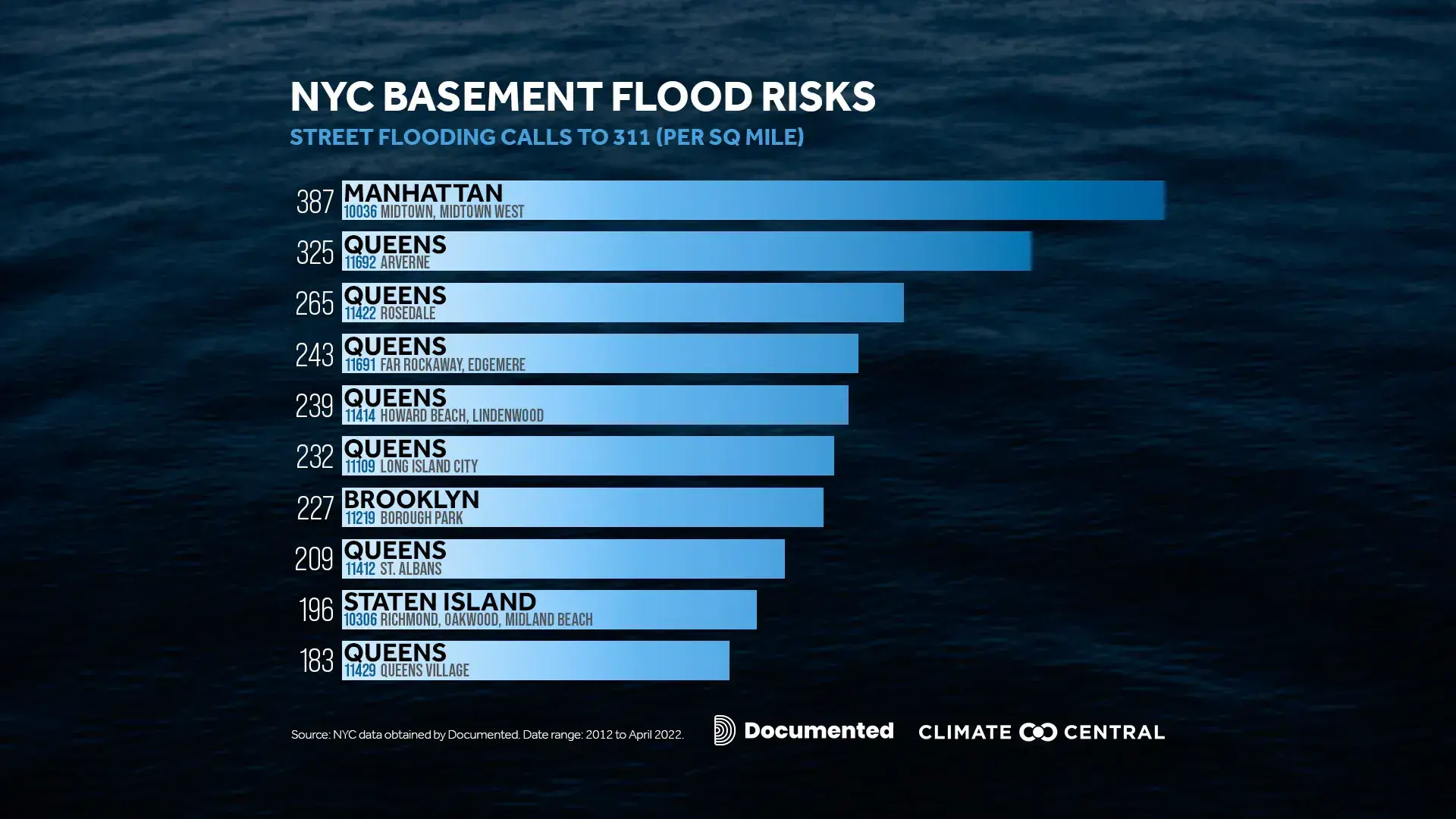

A heatmap created by Documented and Climate Central using records of 311 flooding calls and records of more than 7,000 illegal basements verified by the Housing and Preservation Department reveals how these vulnerable homes tend to be concentrated in flood-prone locations. The majority of these units are in Brooklyn and Queens, where census data shows more than a third of residents were born abroad.

Victoria Sanders, a research analyst at the NYC Environmental Justice Alliance, which advocates for improved environmental conditions, says the City’s efforts to mitigate future storm damages in immigrant communities focus “mostly on short-term recovery, emergency response and communications, and individual responsibility to be prepared and/or flood-proof.”

In 2019, the City tried implementing a pilot program to convert basement apartments into safe apartments, but the efforts were lost during the COVID-19 pandemic. Documented learned that when the DOB assessed Amit’s home for damages after the storm, the department found evidence of an illegal apartment in the basement, however the Shivprasads have not been cited by the agency.

“We Are in for a Long Run”

The water had started to recede when Amit opened the door to the basement, but it was already too late by the time he tried to jump in to rescue Pramatee and Dameshwar’s son, Krishna.

The wall had collapsed on one side, which enabled the water that was building outside — and not receding into the sewers — to pour in and fill the apartment.

“If I could have made a difference, if I could have saved anyone by just opening that door, then it wouldn’t have mattered if I got injured,” Amit said.

When the NYPD arrived at the location around 11:45 p.m., they found Pramatee and Krishna Ramskriet’s unconscious bodies. Dameshwar and his other child survived. In total, Hurricane Ida took the lives of 13 New York City residents — eleven of whom lived in basement apartments.

Amit did not sleep the rest of the night. He stayed up talking on the phone and calling the Red Cross to try to get temporary housing for his neighbors. His parents slept in his car.

The day after the storm, City and state officials, including Gov. Kathy Hochul and former Mayor Bill de Blasio, visited the neighborhood and issued a press release addressing the damages, announcing plans to help prepare for future storms.

Amit was outside his home and said the politicians did not speak with any of the homeowners. At that point, with his clothes drenched from the night before, he remembers telling himself: “We are in for a long run.”

Hazel Crampton-Hays, press secretary for Governor Hochul, said that representatives from the Governor’s office spoke with homeowners in the neighborhood that day, and continued to communicate with impacted homeowners to offer state support, as well as support from federal and nonprofit partners.

Amit spotted Schumer, whom he had previously met, and approached him to ask for help for his neighbors. He says he was told to send an email, which he did, asking to meet with them to discuss assistance for his neighborhood. He says Schumer’s office met with him and other residents over Zoom and told him about the senator’s plans to push for federal assistance.

Four days later, on Sept. 5, President Biden declared Hurricane Ida a natural disaster, allocating $594 million of federal funds for the families affected by the storm in New York. But until the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) assistance could arrive, Amit’s family had to find temporary housing while looking for funds to construct emergency bracing to prevent the house from collapsing, which amounted to $65,000.

Unable to get financial assistance from his homeowner’s insurance company because it did not cover damages from natural disasters — as they did not sell flood insurance in the area by the time of Ida — Amit and his father contacted FEMA.

FEMA inspectors visited the street to assess the damages caused by the storm. The agency, combined with a $169,000 loan from Small Business Administration (SBA), provided Amit’s family with $175,000 — 51% of the $328,000 they eventually spent on repairs. They used their savings to pay the remaining repair costs. The point about how small a fraction of costs were covered was reiterated to Documented by 10 homeowners, including from other blocks in Queens that flooded during Ida.

“It didn’t surprise me at all because when they did the inspection they stood outside the house, so how are they going to see anything that happened?” Amit said.

A FEMA spokesperson said that due to Covid-19 “inspectors assessed damages from outside of the homes,” and added that the maximum grant for disaster assistance is $36,000 for each qualifying individual.

All told, 4,703 people who suffered property damages due to the storm filed claims against the City to ask for additional assistance but were denied because a 1907 ruling stated the City is “not liable for damage from ‘extraordinary and excessive rainfalls.’ ”

In 2022, survivor Dameshar Ramskriet sued Amit, his father, and the City for negligence. The lawsuit claims the three parties were “negligent, careless and reckless” about the maintenance and inspection of the sewer system in the premises.

Documented reached out to the Ramskriet family multiple times, but they declined to comment. When Documented contacted Max Silverberg, associate trial attorney at Sonin & Genis, the firm representing the Ramskriet family, he responded with the following statement: “We continue to believe this preventable tragedy occurred as the result of unnecessary negligence. We intend to ensure the people and entities responsible for this tragedy are held responsible. We dispute the statements of anyone trying to place blame or responsibility on the two individuals who were killed.”

Amit says he felt hurt when he learned a lawsuit had been filed against him and his father, but that he was determined to continue his advocacy so that the City and state would take his neighborhood seriously.

Years later, the death of his friends and tenants are “still hard to believe,” he said.

Around August of 2022, nearly a year after Pramatee and Krishna lost their lives and 15 years since Amit experienced his first flood, the City installed a new traffic sign in front of Amit’s house reading: Road May Flood.

But Amit says the road has been flooding and will continue to flood. Data from 311 calls show that Amit’s block has flooded every year in the last twelve years.

“They should have said ‘this road will flood’ instead,” Amit said, adding that the fact that it took the City so long to add the sign to the street shows how disconnected they are from the experiences of the residents of the neighborhood. “They just don’t care.”

His father Ragendra shared the same sentiment and said unless there is help from the City or state to lift the homes or offer buyouts, the sign would do little to help weather upcoming storms.

Waiting for the Next Storm

On New Year’s Eve of 2022, Amit was in high spirits. Nearly 18 months after the storm, repairs on the house were almost complete and he was preparing for an inspection from the Department of Buildings.

The hole in the wall left by Hurricane Ida had been covered. In the basement floor, workers installed multiple 3-inch wide holes designed to direct water into a new pump system that can expel 3,000 gallons of water per minute.

The driveway was redesigned, too. It had a barely noticeable indentation in the middle that resembled a canal “so that the water can flow out onto the street,” Amit said. His father demonstrated by throwing a bucket of water onto the pavement and watching it flow into the middle and then onto the sidewalk.

“We are trying to do the best that we can to make sure we are prepared for the next flood,” Amit said.

But all this has come at a high cost. Not just monetary — as it ended up costing the family $328,000, with $125,000 coming from the family’s life savings — but also emotionally and physically. They have spent entire days cleaning, painting and fixing a house that they have been making repayments for despite being unable to live there. Ragendra, who retired in 2020, says he feels like he has started to work again.

Amit has continued to advocate for his block by reaching out to district leaders, including local City Councilmember Linda Lee, who took office in 2021 following the hurricane. He says Lee visited his home at the end of January and has had talks to see how she can best assist the homeowners in the block.

On March 27, weeks after Amit moved back into his home, his block was added to the map of “Climate Disadvantaged” communities, which will receive priority spending in projects aimed at reducing gas emissions and pollution.

“I made a promise to everyone,” Amit says, “that I was going to get them help and make sure that this community is not forgotten.”

But there is uncertainty in his voice. The alterations they made in the past protected their home from flooding for 14 years until the unthinkable happened. Only time will tell if the new changes will prevent future floods.