While a group of lobbyists linked to hydrocarbon and timber business groups are demanding the repeal of the PIACI Law that protects Indigenous people in isolation and initial contact, in Ucayali, the last Iskonawa, a population in initial contact, are fighting for their rights, their territory, and their survival.

Peru’s last Indigenous Iskonawa community living in voluntary isolation has been trying to save its land and way of life after a mock communal assembly decided to sell it all. One family has taken control of the Chachibai community’s representative bodies and, in turn, of the land’s natural resources.

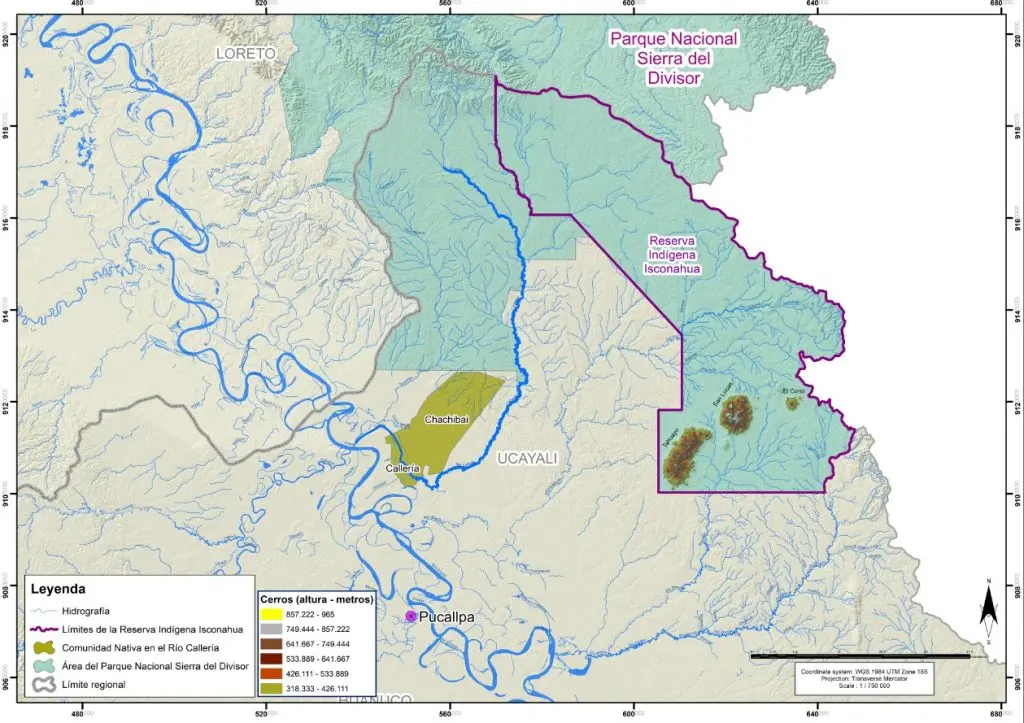

In the Department of Loreto, Peru’s large rainforest region, hydrocarbon and logging businesses have been lobbying to repeal a law that protects Indigenous People Living in Isolation and Initial Contact (PIACI). Meanwhile, in the neighboring Department of Ucayali, the Ishkonawa people of Chachibai are waging a battle for their rights, territory, and survival.

Whistleblowers and others in possession of sensitive information of public concern can now securely and confidentially share tips, documents, and data with the Pulitzer Center’s Rainforest Investigations Network (RIN), its editors, and journalists.

The Chachibai are the last Iskonawa Indigenous group in stages of 'Initial Contact.' The entirety of their land, which makes up more than 20,000 hectares, is about to be sold, and they were not consulted about this.

On paper, the decision to sell received unanimous support from the communal assembly. However, there is an important caveat. Chachibai is an Iskonawa and Shipiba Indigenous community, as it is identified in the records of the Ministry of Agrarian Development and in the database of the Ministry of Culture. But only one Iskonawa Indigenous person is registered in the communal register, and almost none of the people who have lived in the community since before its titling are registered.

This means that none of the residents who have lived in Chachibai for more than 20 years are formally part of the community. The register book, the minute book, and all the documents of the community are in the hands of the Mori Guimaraes family.

The communal assembly that decided on the sale is chaired by Arturo Mori Guimaraes. The Mori Guimaraes family has long held the presidency of the community and denies any opportunity for participation or rights to the Iskonawa, who are the legitimate owners of the land.

Being left out of decision making and being forced into a system that is out of their control is unfortunately nothing new for the Iskonawa people, who have fought hard to be recognized by Peru’s government.

“We want our own territory, because the Iskonawa, apart from the Chachibai, historically have walked a long way so that the Peruvian State can include us in the affairs of the Indigenous Reserve,” said Félix Ochavano Rodríguez, president of the Organization for the Development and Common Good of the Iskonawa People (ODEBPI).

It All Started With Timber

The irregularities in the management of the resources of the Chachibai community date back to the first years after the titling of the communal lands in 2007. Arturo Mori and his family took control of the community, and they negotiated with forestry companies to sell Chachibai wood.

A year later, in May 2008, the “community,” represented by the Mori family, signed an exclusive contract with timber company N & H SRL that was not very beneficial for the community.

The company later pulled out because Mori kept asking for money advances. In 2013, Arturo's brother, Rusber Mori Guimaraes, became head of the communal assembly and made a deal with another company, which would pay them less for the timber. The deal fell through again, and the community ended up being fined.

How the Community Lost on Two Timber Deals

N & H SRL, owned by the Weller brothers and José Manuel Noriega, agreed to pay an advance of $27,000 to be the exclusive buyer of the community’s wood but only paid a quarter of that. The same contract states that the Chachibai were obliged to provide the personnel for the reforestation and enrichment of the forest, at their own cost.

Moreover, the “community” signed another agreement to pay $27,000 for the companies’ expenses to get the land title, giving N&H three years to pay it back from profit made on selling the wood.

In August, they signed another agreement, granting the company the rights to extract wood from the forest over the entire communal territory for 15 years, adding that N & H may assign the contract to any other company.

In return, the community would receive about $5,000 per year as payment and in the event of any breach, the community has to pay N & H about $270,000.

Getting paid for the wood did not go according to plan. In 2010, the community should have received $95,000 (368,685 soles) and in 2013 around $31,000 (122,047 soles) based on the amount of wood extracted by the community of the “Tornillo” Cedrelinga catenaeformis species and the local market prices at the time. But the company could not keep up with the money demands, according to its owners.

“Arturo constantly asked for advances on the money,” owner José Manuel Noriega said while discussing the payments up to 2012. “As a company we could not meet these unplanned orders.”

“We as a company were already in charge of our own concession and decided to stop working in the community; we could not meet so many demands for money,” he added. “In those years, we tried to reconcile the Iskonawa with the Mori family, but I don't know if that has been achieved. We did not intervene in the internal messes of the community.”

The owners state that they gave money to the Iskonawa, “perhaps not in the amount that corresponded to them, but we did it.”

“We try to be a responsible company,” they added.

By July 2013, the Chachibai communal board, now headed by Arturo Mori’s brother Rusber Mori Guimaraes, signed a contract with a new company called Flor de Ucayali SAC.

The company lowered the price per foot of timber from $0.25 (1 sol) to $0.16 (60 cents sol) and acknowledged a debt of $4,326 (16,700 soles) to the community, which would be deducted from the sale of the wood.

Flor de Ucayali’s directors agreed to pay $17,000 (65,000 soles) and added that, at the end of 2014 when they would have finished extraction, the company would deliver an additional $5,200 (20,000 soles) as compensation for any damages.

There is no information available publicly as to why this agreement ended. However, during 2014 and 2015, when Flor de Ucayali was operating in Chachibai, the community was fined by the Supervision Agency for Forest and Fauna Resources. The amount of the fine was 20,698 soles (almost US$5,550 today), according to the 2017 legal resolution.

By August 2019, Arturo Mori was once again president of the communal board, and he proposed a sale of the entire communal territory, arguing that abandonment by the state, illegal mining, and drug trafficking were threatening the territory.

The assembly gave authority to the community member Bilberto Mori Sánchez to carry out the sales procedures. At his home on April 21, 2021, another relative of Arturo Mori, Lener Mori Reátegu, by then the new president of the communal board, received $3,900 (15,000 soles) from Forestal E & F.

For unknown reasons, the sales efforts were not successful. On April 21, 2021, the new head of the community, Lener Mori Reátegui, at the home of Mr. Bilberto Mori Sánchez, received the sum of 15,000 soles from Forestal E & F, a company created in 2020 and managed by Isidro Kawajigashi Espinoza.

After this, Forestal E & F had the rights to exploit the Chachibai forest. Again, without any permission from the Iskonawa people.

On August 26, 2021, Lener Mori Reátegui met with the representatives of N & H. At the meeting, Lener Mori committed Chachibai to a payment of up to 200,000 soles for the debt initially contracted with the company for the titling of the community. However, Weller Noriega, as a representative of N & H, indicated that the company maintained the intention to be able to conclude the current logging contract.

The Iskonawa People Take Action

Currently, the Iskonawa people are incorporated as the Organization for the Development and Common Good of the Iskonawa People (ODEBPI). They have made the decision to more actively pursue the claim to recover their ancient territory. Years of appealing to the boards of directors of Indigenous organizations like the local seat of AIDESEP, ORAU and the Federation of the Native Communities of Ucayali and Affluents (FECONAU) to speak with authorities have only left them disappointed.

“We got the feeling that no one cares about us, other than a couple of allies, academics, and journalists who once reached out to us. We are tired of being objects of study. We are tired of rejection, of contempt, of being insulted. For us, this is over,” said the communal leader of the Iskonawa of Chachibai, Ms. Ruth Rodriguez Campos.

According to other leaders of the Iskonawa peoples, Gessica Pérez, William and Félix Ochavano, as well as other community members, the community's board of directors led by the Mori family does not call for the development of the general assemblies despite the fact that they are living in the community. They are never called to participate in the assemblies that supposedly take place.

Two community members, Luisa Díaz Maynas and Carlos Ochavano Guimaraes, filed a complaint for forgery of signatures in 2019 against Arturo Mori Guimaraes.

The Iskonawa villagers have started a lawsuit to retake control of their community. The Iskonawa of Chachibai, and some Shipibos who live there, demand that the communal register be purged, made to include them, and that the people who have been irregularly included as community members without ever having lived in the community are removed from it. They have presented a refined register, verified in the field by a justice of the peace that they themselves have taken to the community.

The 3rd Judicial Peace Court is currently analyzing a request by the community to order the convening of a General Assembly in Chachibai. They want the Assembly to include Indigenous people in the community register, to remove the current members of the communal board, organize an election of new members, and grant these new members the power to register public records.

The Iskonawa have turned to the Ministry of Culture to receive the support that they are entitled to as Indigenous people in Initial Contact.

Unfortunately, they have been waiting for more than two months to get any kind of response.

Retaliation

The current directors of FECONAU have been more proactive than their predecessors. After discovering how the Mori Guimaraes family had taken advantage of the Iskonawa population, FECONAU questioned their actions. In response, Lener Mori decided to disaffiliate Chachibai from the federation.

Additionally, complaints have been filed against several of the Iskonawa, charging them with the crime of drug trafficking and illegal logging within communal lands. Lener Mori has claimed that the Iskonawa are illegal loggers. The evidence they present are photos of deforestation in the Quebrada Negraf sector, where years ago Hilder Pérez (see previous report) tried to invade the community.

Lener Mori and his uncle, Medardo Mori, accused the community members of Chachibai of illegal logging at the First Corporate Provincial Prosecutor's Office Specialized in Environmental Matters of Ucayali. Their basis: In a communal agreement, the community members decided to extract wood from their farms to rebuild their houses and repair the precarious school that they hope to put into operation in the community.

Felix Ochavano and William Ochavano, leaders of the Iskonawa Association, refer to the complaints as follows: “They are tricks. They are so used to getting away with it, that no one tells them anything about their mishandling. That's why they denounce us now. They are at the point where they can no longer continue to cover up all their abuses and thefts […].”

From a History of Abuse to a Future of Affirmation

The history of the Iskonawa and the Paucar people is probably one of the most painful stories of the Peruvian Amazon. Since the first contact, which occurred in 1959, the abuses committed against them have not stopped. Mestizos, oil barons, rubber tappers, and other groups have been threatening their livelihoods, and sometimes lives, ever since.

"What we see is a continuation of the violation of the rights of Indigenous peoples, who are being stripped of their territory, on which their identity also depends," explains Carolina Rodriguez, an anthropologist and linguist, specialized in the history of the Iskonawa people.

Roberto Zaquirey, also a linguist, volunteers at the Iskonawa School (Escuelita Iskonawa), which aims to strengthen Iskonawa culture. He sees the situation of the Chachibai community as an example of many “humiliations” and Indigenous rights abuses the Iskonawa have been facing in recent years.

“Since their initial contact in 1959, the Iskonawa have not been able to make decisions about their future and have not had the opportunity to build their history as a people,” he said.

“Missionaries, mestizos, state agents, and actors from other towns have made decisions about where and how they should live. They have even denied [the Iskonawas'] existence. When they begin to organize themselves as a people and to relate to the territory that the State has granted them, someone again appears who decides for them, this time breaking the law and openly violating rights recognized by the law.”

A history of contacts

Since before the definitive contact, when missionaries from the South American Mission (SAM) made contact with the Iskonawa who had approached the Callería river basin, near Cerro El Cono, the Iskonawa were already aware of the danger of contact with other groups.

They knew of the mestizos who they suspected wanted to kill them and had been confronted and expelled by the Brazilian oil tankers at the point of pellets and bullets. They would have come across the rubber tappers, and after a short time they fled from the abuses. They also had constant conflicts with other groups from the north in Sierra del Divisor, possibly the so-called Remo, whom have been known for two centuries.

However, the Iskonawa, then led by Chachi Bai, sensing the imminence of being dominated by the mestizos or annihilated by other rival groups, preferred to go with the missionaries, who took them to a military base where they remained for a few months, perhaps one or two years, and where many became sick and died from European diseases.

The missionaries left the country with the promise of returning. They returned three years later, when the Iskonawa, hopeless, had withdrawn to a town called Jerusalem. The prejudices there of the Indigenous Shipibo against the Iskonawa, whom they called "calatos" and "savages," motivated a diaspora during which some Iskonawa moved away to Pucallpa, and others returned to the basin from which they were extracted, Callería.

Over the years, tired of the mistreatment, they decided to move further inland and try to have their own community, which they named Chachibai. Chachibai was going to be the last refuge of the Iskonawa. In the midst of the recognition and titling process of the community, some Shipibo who advised them on the paperwork to get the title offered to take charge of the entire process. Thus, the community went from being the land of the Iskonawas to becoming a Shipibo-Iskonawa community.

For a few months now, Zariquiey, and other volunteers, have been developing the Iskonawa School together with the Iskonawa children from Callería, in an effort to continue strengthening a language and a culture that was about to be lost forever.

Now a new generation of children is learning the traditions and words with which the world is defined in the jungle kingdom of the Iskonawa.

In face of the rights abuses, the Iskonawa people continue to reaffirm their language and culture, and they show their strength in openness to include other communities, according to Zariquiey.

“The Iskonawa have opened the doors of the little school to the Shipibo boys and girls of Callería, promoting a true interculturality, far from any chauvinism,” he said. “Most Iskonawa have Shipibo blood running through their veins, and they are aware of that heritage, which they treat with respect and affection. It is what they expect from their Shipibo brothers: respect and affection. What happened in Chachibai generates pain and discord, but the Iskonawa will continue to fight for their rights and for their lives.”

ODEBPI President Félix Ochavano Rodríguez says that the association formed “to participate in the care of our relatives who continue to live in the forest, because there are some who are still in the forest; because we want to preserve our culture.”

“We as a people need to be recognized—socially, culturally, and economically. We want to protect our resources and recover our legacy,” he said.

At this moment, the Judicial Power of Ucayali has in its hands the decision to either perpetuate the historical abuse, or, at last, to recognize justice for the Iskonawa people, the sons of the paucar.

The Mori Guimaraes family could not be reached for comment.

This research was produced in partnership with the Pulitzer Center's Rainforest Investigations Network.