When police took Carlos Yazzie to jail on the Navajo Nation in New Mexico after his arrest on a bench warrant in January 2017, he needed immediate medical attention. His foot was swollen and his blood alcohol content was nearly six times the legal limit.

But law enforcement decided that he was fine, jail records show. They put Yazzie in a cramped isolation cell at the Shiprock District Department of Corrections facility instead of taking him to a hospital and then left him unmonitored for six hours without periodic staff checks as required, according to an investigative report. When a guard handing out inmate jumpsuits the next morning stopped at Yazzie's cell, the 44-year-old day laborer was dead. It would later be determined in an autopsy that he died from acute alcohol poisoning, which is easily treatable by medical professionals, experts said.

"These correctional officers are basically holding these lives in their hands with their decisions," said Chris Yazzie, Carlos' brother, who once worked as a correctional officer at the jail where his brother died but did not know the specific officers. "I don't think these people are prepared."

Yazzie is one of at least 19 men and women who have died since 2016 in tribal detention centers overseen by the Interior Department's Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA), according to an investigation by NPR and the Mountain West News Bureau, a collaboration of NPR member stations. Several of them died after correctional officers failed to provide proper and timely medical care, records show. Many of the victims had been arrested for minor infractions, such as petty theft or violating open-container laws, and were awaiting trial. In some cases, BIA officials have not released details of inmate deaths, despite repeated written requests.

Federal officials have known about the mistreatment of inmates and other problems at the detention centers for nearly two decades. A 2004 federal investigation found widespread deaths, inmate abuse, attempted suicides, inhumane conditions and other issues in many of the more than 70 detention centers scattered throughout the U.S., including in Arizona, New Mexico, Montana, Wisconsin and Mississippi. The Interior Department's inspector general told congressional lawmakers during a hearing on the matter then that the facilities were a "national disgrace."

Seventeen years later, myriad problems remain, according to more than two dozen interviews with investigators, law enforcement, lawmakers and victims' relatives, as well as a review of hundreds of pages of documents, including autopsy reports, jail logs, internal government reports and lawsuits.

Among the findings:

- Poor staff training and neglect led to several inmate deaths that could have been prevented.

- Correctional officers at several detention centers often violated federal policy and standards by not checking on inmates regularly or ensuring that they received medical care. In one instance, a 22-year-old man died in a holding cell, but his body wasn't discovered for nearly three hours.

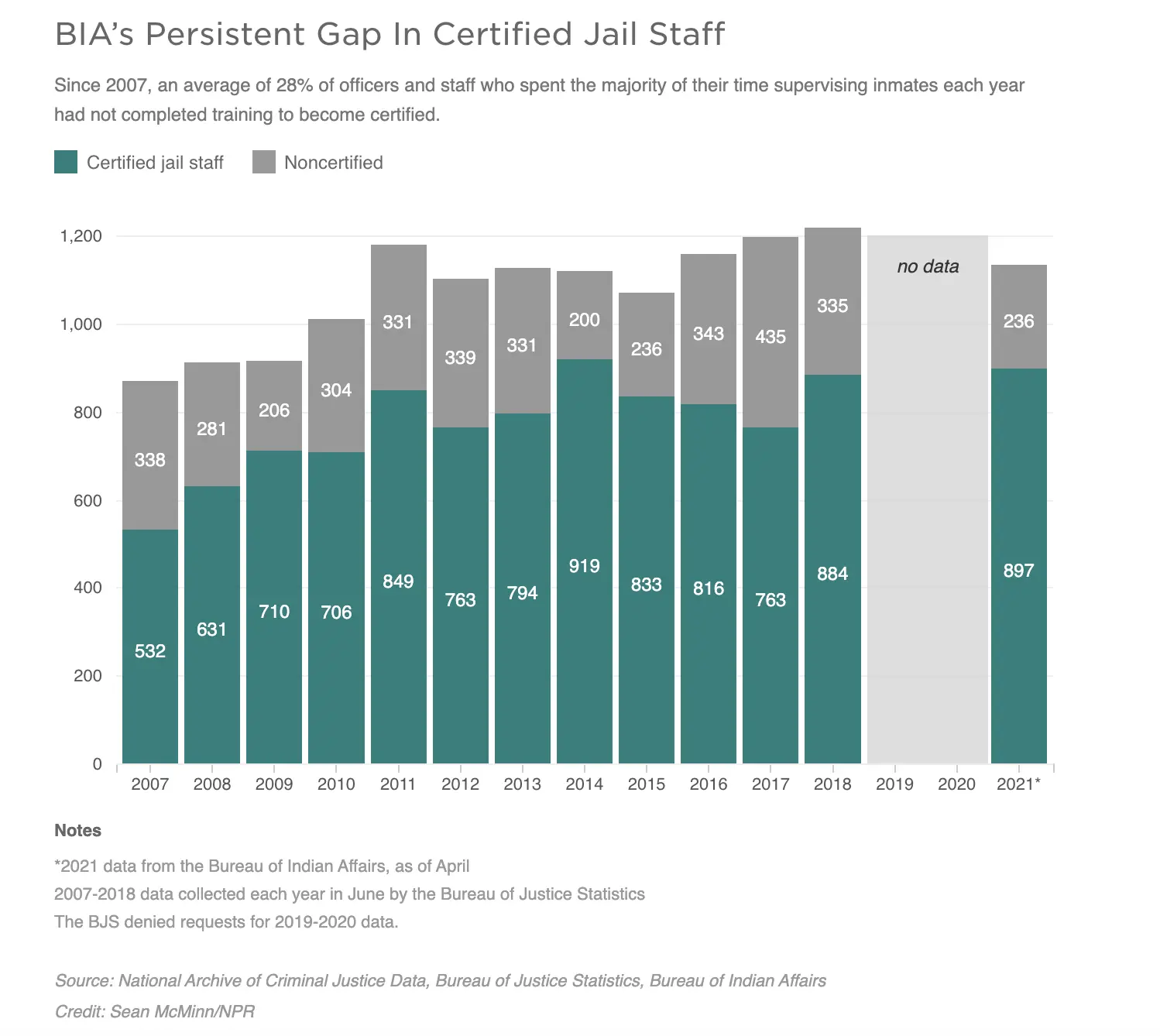

- One in five correctional officers assigned to the detention centers as of April has not completed the required basic training, which includes CPR, first aid and suicide prevention.

- Several of the detention centers have been in disrepair for years, with overflowing toilets, broken pipes and rust in the water. At least one facility lacked potable drinking water, forcing jail administrators to turn to charities for bottled drinking water.

- Congress has chronically underfunded the detention centers, despite repeated investigations that found the facilities were short staffed and had problems.

Sen. Jon Tester, D-Mont., a member of the Senate Committee on Indian Affairs, said that an "immediate, transparent" investigation is warranted, calling the findings by NPR and the Mountain West News Bureau "deeply disturbing."

"Any wrongdoing or negligence must be reported to Congress and the folks responsible must be held accountable," he said in a written statement. "Where policies are found to have failed, we will work to fix them and ensure it does not happen again."

Rep. Teresa Leger Fernandez, D-N.M., chair of the Subcommittee for Indigenous Peoples of the United States, said the problems at jails overseen by the BIA are "heartbreaking but, sadly, not new." She said her goal is to significantly boost funding for the detention centers and eliminate an estimated $135 million budget shortfall.

Interior Secretary Deb Haaland declined a request for an interview.

A pattern of negligence

Joe Snell was 37 and broad shouldered. He loved shooting Nerf guns with his nieces and nephews and playing practical jokes on his older sister, Michelle.

"I used to tease him that he looked like a ninja turtle," Michelle Snell recalled.

She knew Joe struggled with an addiction to prescription pills, methamphetamine and alcohol. But when he began serving a three-month sentence for a parole violation at a federally operated jail on the Spirit Lake Tribe Reservation in North Dakota, Michelle thought he could kick his addiction and get back on track. He was even taking classes during the five weeks he was there.

"We'd always thought he'd be safe there," she said. "He's good. He's in jail."

But shortly before 3:30 p.m. on March 26, 2020, Snell collapsed while exercising in the jail's day room. He became unconscious before an ambulance arrived, but neither of the two correctional officers on duty, who the BIA said were certified in basic lifesaving techniques, performed CPR or used a defibrillator, also known as an AED, jail records show. The BIA declined to provide certification documents.

"That's [AED] truly a lifesaving device," said Ian Paul, a forensic pathologist at the New Mexico Office of the Medical Investigator, who specializes in emergency medicine. "When someone collapses like that, they really should go for an AED because that's the lifesaving maneuver. As soon as they become unconscious, that's when the AED should be applied."

When the ambulance arrived, paramedics initiated CPR and tried unsuccessfully to save Joe Snell. Michelle Snell said her brother suffered a heart attack, but the North Dakota State Forensic Examiner's Office declined to release Snell's autopsy report, citing state confidentiality laws.

"Why are all these people working there?" Michelle Snell asked.

William McClure, the BIA special agent in charge of the district that oversees the jail on the Spirit Lake Tribe Reservation, declined to comment on Snell's death.

Federal policy requires correctional officers to "initiate all available rescue options" when an inmate is in a life-threatening situation.

Interior Department spokesman Tyler Cherry said guards did not perform CPR or use an AED because Snell had a "pre-existing medical issue which needed to be addressed first by Emergency Medical Service personnel." He declined to elaborate.

"There's no medical condition that prevents one from initiating lifesaving maneuvers such as applying an AED and starting CPR," Paul said.

Michelle Snell said she was unaware of her brother having a preexisting condition.

The incident at the Spirit Lake Tribe Reservation jail isn't an anomaly. When Carlos Yazzie was booked into the Shiprock jail on the morning of Jan. 11, 2017, he was dangerously drunk. His blood alcohol content was about 0.461 — the legal limit is 0.08.

"This level ... has the potential to be lethal, even in a person who is a chronic ethanol user and developed tolerance over time," New Mexico forensic pathologist Lauren Edelman wrote in Yazzie's death investigation report, obtained by NPR and the Mountain West News Bureau.

Federal policy requires guards to transfer inmates to a hospital or other health care facility for a medical examination if they are "extremely intoxicated," but it doesn't define what that means. But neither of the two correctional officers on duty followed the rules. They had also not completed the required basic training at the Indian Police Academy, jail records show. They kept Yazzie in a cell and failed to do checks on him every 30 minutes as required, according to a death investigation report. They found him dead just before dawn.

"I do believe that if they would have taken him to the hospital, the chances of him at least being alive for a little longer would have been great," his brother, Chris Yazzie, said.

As of April, 236 of the 1,133 correctional officers — 1 in 5 — working in tribal detention centers had not completed the required basic training, which includes 400 hours of classes on first aid, suicide prevention and handling emergencies. It has been a chronic issue for years. In 2018, for example, 27% of correctional officers had not completed training, according to the latest federal data released to NPR and the Mountain West News Bureau.

The BIA allows officers up to a year after being hired to become certified, but it sometimes takes longer, according to interviews with correctional staff and federal investigators. In one instance, a correctional officer on the Navajo Nation has waited more than two years to enter the police academy and was recently denied admittance because the class was full.

Calls for reform

In June 2004, then-Interior Department Inspector General Earl Devaney was blunt when he testified before the U.S. Senate Committee on Indian Affairs about an investigation into the tribal jails program.

"BIA's detention program is riddled with problems and, in our opinion, is a national disgrace, with many facilities having conditions comparable to those found in Third World countries," he told lawmakers.

His investigation found more than 800 serious incidents, including deaths, attempted suicides and escapes. One man was found hanging in his cell at the Shiprock jail after being left unmonitored for two hours. Another inmate died from a seizure. A female inmate in a windowless cell on the Yakama Reservation in Washington state had not seen daylight in nearly two weeks.

"I think 12 days without seeing sunshine in a windowless cell would drive someone to attempt suicide," Devaney told lawmakers.

Most of the incidents — 98% — were never reported to top BIA officials, the investigation revealed.

Devaney also found that some jails had broken ventilation systems, toilets that didn't flush and sinks that didn't work. And he learned that the facilities were severely understaffed. In some instances, jail cooks and dispatchers had to fill in as guards.

Then-Sen. Ben Nighthorse Campbell, R-Colo., who chaired the congressional committee, introduced a bill in 2004 to reform the detention centers, but it never got Senate support. Still, the BIA promised change.

"I hope this will not be one of those 'gathering dust' reports," Sen. Timothy Johnson, D-S.D., said at the time.

While Congress increased funding for the BIA detention program following Devaney's report, a 2011 follow-up investigation found that the agency didn't use the money as intended to address staffing shortages and improve facilities. Again, the BIA pledged to make improvements.

A third inspector general investigation in 2016 found that some changes had occurred. The BIA created a corrections handbook for guards, and the percentage of certified officers grew to about 70%. Officials also rebuilt two dozen of the 77 jails.

But problems still exist. Inmate deaths continue, many jails remain in disrepair and the agency struggles with hiring and retaining correctional officers. A survey last year found that 42% of correctional facilities are understaffed, and there's a lack of funding to properly staff and operate the detention centers.

Devaney, who is retired from the federal government and lives in Florida, did not respond to a request for comment from NPR and the Mountain West News Bureau. Ed Naranjo, a former BIA official and whistleblower who helped spark the 2004 investigation, said he isn't surprised that problems persist.

"There's not enough resources and people to address these issues," Naranjo said. "I think another thorough inspector general investigation is needed. A visit and inspection of each one of the facilities has to be done."

At the Window Rock District Department of Corrections in Arizona, the heater is broken, the pipes are deteriorating and the drinking water is often brown.

"We don't want inmates to drink it because it does not taste like water," said Lt. Ophelia Begay, who runs the facility and recently gave a tour to NPR and the Mountain West News Bureau.

The jail is supposed to have three to four correctional officers on duty per shift but has only two, and they also work as the jail's janitors, cooks and transport team, she said. When an inmate needs to go to the hospital, one of the guards has to take the inmate, leaving the other guard alone, often for hours.

"I need the manpower," Begay said, unapologetically. "We need funds."

Navajo Department of Corrections Director Delores Greyeyes said that Window Rock has only 10 full-time employees, half of what is needed. Greyeyes estimates she needs about twice the amount of federal funding to adequately staff and operate her corrections program.

"People don't understand the sheer number of correctional officers that are needed to work a facility in order to keep people safe and to see what's happening around the corridor," Greyeyes said.

Greyeyes said she reached out to the Justice Department and tribal leadership for money to replace four jails on the Navajo Nation over the past two decades. Some of the new facilities have medical wings and plans for substance abuse treatment programs. But they haven't received enough funding from the Bureau of Indian Affairs to fully staff them.

The BIA also does not require detention centers to have on-site medical personnel. Instead, they contract with nearby hospitals or clinics operated by the Indian Health Service. IHS spokeswoman Asha Petoskey said her agency provides "intermittent" care for inmates. So it's often left up to correctional officers or other law enforcement personnel to decide whether someone is sick or injured enough to go to a hospital.

"We're not doctors," said Hansen Attakai, a correctional officer with the Navajo Department of Corrections. "We don't have all the knowledge that they have."

Other correctional facilities overseen by the federal government have on-site medical personnel.

In 2017, the National Congress of American Indians, an advocacy group that represents tribal communities, passed a resolution urging the BIA to ask Congress for money to place medical personnel in its jails, arguing that the current situation puts a strain on tribal jails and "exacerbates the already challenging problem of health disparities for American Indians."

Indigenous people have some of the highest substance abuse rates in the country because they're a high-risk population, according to federal government statistics. About one-third of all people booked into tribal jails are arrested on drug- or alcohol-related charges.

Native Americans have suffered historical, generational trauma since the federal government took Indigenous land, systemically broke their culture and shattered families. That created poverty, health disparities, premature death and domestic violence on some reservations and fed into high rates of addiction, according to Brandy Tomhave, a lawyer and member of the Choctaw Nation who runs a tribal advocacy firm in Washington, D.C.

"The challenges that American Indian families face on reservations exceed the wildest imagination of most Americans," she said. "Some folks cope with that by abusing substances."

Tomhave has long advocated for the federal government to fund on-site medical personnel in jails to care for Native Americans, saying they have a responsibility to provide adequate health care for inmates. This duty stems from treaty obligations in which tribes gave up their land in exchange for promises of health, safety and security from the U.S. government.

"The federal government has chosen to ignore their legal obligation to provide appropriate staffing and programming in the form of medical care inside tribal jails," she said. "That decision has gotten people killed."

Tester, the senator from Montana, said he will urge the Biden administration to focus on the funding problems dogging the detention centers.

"I'm going to keep pushing aggressively to make sure folks working in Native communities have the resources they need to do their jobs correctly and effectively," Tester said in a written statement to NPR and the Mountain West News Bureau.

"She knew she was sick"

Having a medical expert at the federally operated detention center in Browning, Mont., may have saved Brandy Skunkcap's life. She was arrested on the Blackfeet Indian Reservation for allegedly stealing two beers from a gas station in 2016. Skunkcap, 32, was transient and had struggled with alcohol and painkillers since she was a teenager. Her liver was scarred from cirrhosis, and a few weeks prior to her death, she had been in a hospital because she was vomiting blood, a coroner's report found.

"She knew she was sick," said Terra Brauhn, Skunkcap's sister-in-law. "We could tell it was taking a toll on her body. You could just tell by looking at her. Very small. Very frail. Her teeth were falling out."

Correctional officers are mandated to perform a physical and mental health screening upon an inmate's arrival at a jail, according to BIA health and safety standards, which also require them to ask about past medical conditions, as well as alcohol and drug dependency, and to look for any behavioral or physical abnormalities.

Skunkcap was intoxicated when a correctional officer booked her into the Blackfeet Adult Detention Center shortly before 9 p.m. on March 23, 2016, records show. The guard decided that Skunkcap wasn't ill enough to warrant a trip to the hospital, so he just locked her up, jail records show. He also failed to note on the intake form that she was jaundiced and complained of being in pain, a violation of federal policy, the record shows.

At 6:12 p.m. the following day, Skunkcap had what appeared to be an alcohol withdrawal seizure as her cellmate watched helplessly. It was all captured on surveillance video, but guards missed it. When they checked on Skunkcap nearly 90 minutes later, she was "unresponsive" in her bed, according to jail records. Correctional officers violated federal policy and failed to initiate immediate first aid, jail records show. Instead, it took six minutes before a tribal police officer arrived and began lifesaving measures.

Every tribal correctional facility is required to have a working defibrillator on-site, but an Interior Department spokesman declined to say whether there was one, and if so, guards didn't retrieve it, law enforcement records show.

An ambulance arrived and took Skunkcap to the hospital, where she was pronounced dead.

The correctional officer who booked Skunkcap later told the coroner that he noticed Skunkcap had "a yellowish tint" to her skin and had complained of not feeling well. But he never noted those ailments on her inmate medical screening form, jail records show. David Mathis, a California physician who specializes in prison health care, said that this failure highlights a systemic problem within BIA detention centers.

"You cannot ask a correctional officer to make a medical decision," he said.

For years, details about Skunkcap's death were hidden from her family. Her brother, Keith Skunkcap, said he tried to find out what happened to her but was rebuffed by authorities.

"It's just going to be one of these [cases]," he thought at the time. "Just another Native dead."

Over the next four years, at least two other inmates would die at the same facility in a similar manner, records show.

Ignoring cries for help

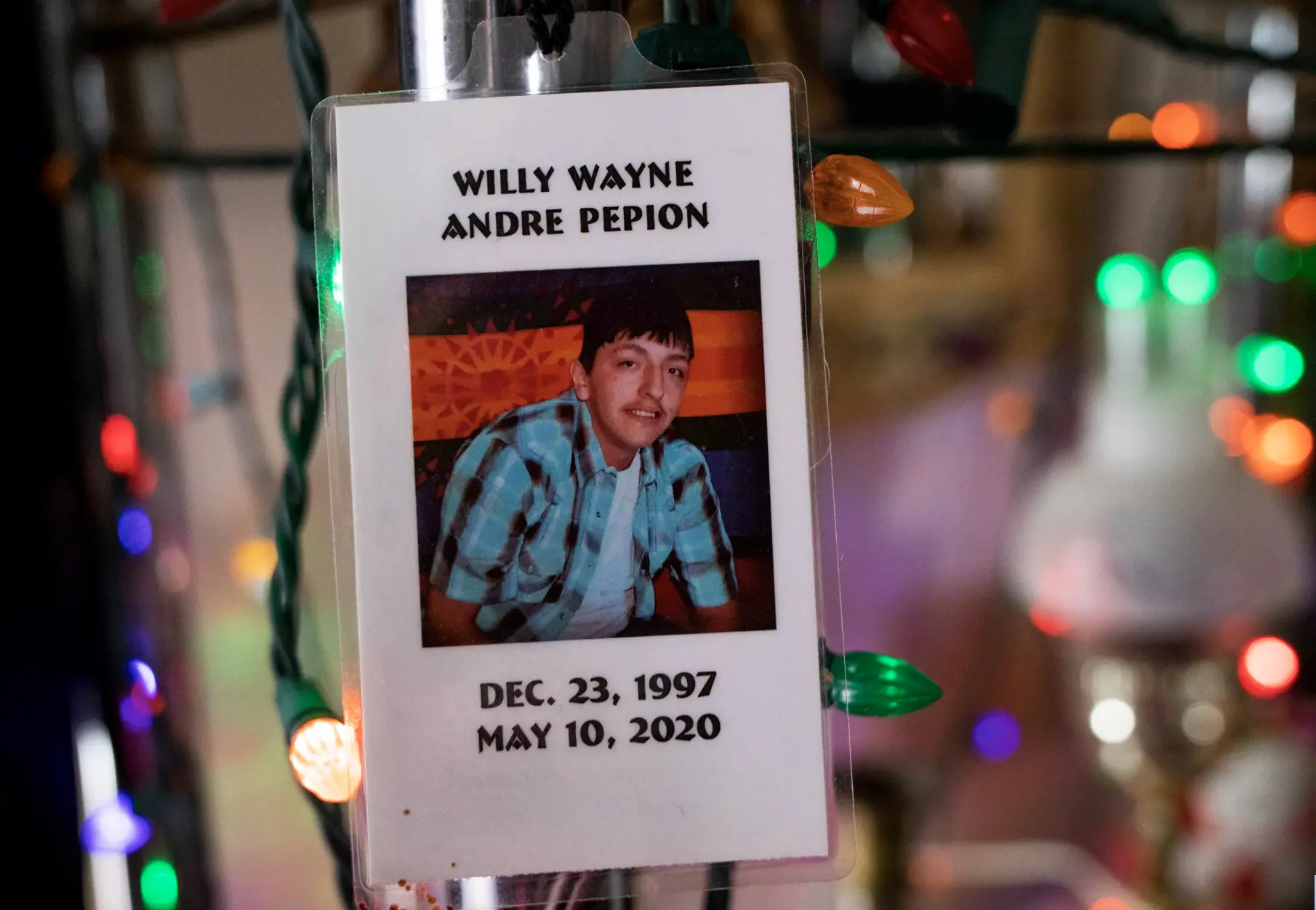

Wilma Fleury knew something was wrong when her 22-year-old son, Willy Wayne Andre Pepion, didn't come home the morning of May 10, 2020. It was Mother's Day, and she was surprised when she awoke and found the house empty. Pepion had gone out the night before in Browning on the Blackfeet Indian Reservation.

The phone rang. It was Pepion's girlfriend calling to say that he was in jail. This wasn't his first time. He had been arrested for disorderly conduct. He had also been drinking.

"He was in there before for being drunk," Fleury recalled in an interview at her home in Browning. "But all of his friends would also be in there."

Spending a night at the Blackfeet Adult Detention Center is almost a rite of passage for young men and women in Browning, a town on the edge of the Rocky Mountains that is home to about 1,000 residents. Police round up underage drinkers and young adults nearly every weekend for alcohol possession or open-container violations. Even Fleury had spent time in that jail, so she wasn't too concerned.

But as the day progressed, her boy still wasn't home. Fleury called the detention center every few hours. Guards told her that they were waiting until Pepion's blood alcohol content reached zero.

That was the last she heard from them.

Later that evening, a Glacier County sheriff's deputy arrived at Fleury's home to tell her that her son, a young man described by his friends as being soft-spoken and a terrific cook, was dead.

"It was just a nightmare after that," she said, crying while seated at her kitchen table. "I don't hardly remember the week after."

Pepion's girlfriend, who was with him that night, said that he got into a fight with several people he knew in the early morning hours of May 10, according to a confidential report from the Glacier County Sheriff's Office and obtained by NPR and the Mountain West News Bureau.

"Bloody mouth, bloody nose," Jonnetta Tatsey, his girlfriend, said in an interview with NPR and the Mountain West News Bureau. "They were even kicking him in the stomach."

A woman then struck the 280-pound Pepion in the head with a heavy object, possibly a shovel or something similar, Tatsey told authorities. He blacked out briefly, she said. Police arrived, arrested him and took him to the hospital. A physician examined Pepion and cleared him at 6:30 a.m. Authorities took him to jail and placed him in the drunk tank. He was free to leave once he sobered up, records show.

Ian Paul, the forensic pathologist, criticized the doctor's decision, saying that an "acutely intoxicated person" should not be medically cleared, because there could be other injuries. In Pepion's case, he could have had a brain injury after being hit in the head, Paul said.

"If he's still ... slurring his words, then that's good evidence that something else is going on and he probably needs a further work-up," Paul said.

Frederick Noon Jr. said he was in jail with Pepion. He remembered watching helplessly as Pepion yelled for guards to take him back to the hospital.

"He was moaning and curled up in the fetal position," Noon said. "He wouldn't let his head touch the mat. I've never heard a grown man cry like that."

No one checked on Pepion for hours, despite a policy requiring correctional officers to do inmate checks every 30 minutes, the confidential report found. When they did, he was dead. The autopsy report found that Pepion suffered a cracked skull "due to blunt force injury" and died from a subdural hematoma.

"What if they would've checked on him?" Tatsey asked.

Pepion's mother still relives that night — and the pain. She cries daily, and when her grief becomes too much, she goes for long walks. It helps.

"But then I get really angry," Fleury said.

After months of repeated written questions and public records requests from NPR and the Mountain West News Bureau, Interior Department officials said they now plan to contract with an outside agency to examine the troubles plaguing the detention centers.

"Under Interior's new leadership, we are seeking increased funding and conducting a comprehensive review of law enforcement policies, practices and resources to ensure that BIA detention center staff are adequately trained, that our facilities are upgraded, and that we respect the rights and dignity of those within our system to the fullest extent," BIA Director Darryl LaCounte said in a written statement.

This story is a collaboration from NPR's Station Investigations Team, which supports local investigative journalism, and the Mountain West News Bureau, a group of NPR member stations covering the region. NPR data editor Sean McMinn and Mountain West News Bureau reporter Savannah Maher contributed to this story.