Autumn

There is no cinema in Sumte. There are no general stores, no pubs, gyms, cafés, markets, schools, doctors, florists, auto shops, or libraries. There are no playgrounds. Some roads are paved, but others scarcely distinguish themselves from the scrub grass and swampy tractor trails surrounding each house, modest plots that grade into the farmland and medieval forests of Lower Saxony. There is no meeting hall. All is private and premodern. You can’t quite hear the eddying rills of the Elbe—the river lies a few miles to the west—but in the cathedral silence of an afternoon in Sumte you might easily imagine you hear flowing water, or a pan flute, or the voice of God. You’re in the great European nowhere, where cows outnumber people and the darkness at night is as unalloyed and mysterious as a silent undersea trench.

One day in October, after a thousand years of evening gloom, a work crew arrives and lines the main avenue with LED streetlamps, which cast a spearmint glow over the chicken coops and the alien corn. The lights are a concession to the villagers—all 102 of them—from their political masters in the nearby town of Amt Neuhaus, who manage Sumte’s affairs and must report to their own masters in Hannover, the state capital of Lower Saxony, who in turn must report to their masters in Berlin, who send emissaries to Brussels, which might as well be Bolivia, so impossibly distant do the villagers find that black hole of tax dollars and goodwill. It’s this vague chain of command that most alienates the people of Sumte. They are pensioners and housepainters. They are farmers, subsistence and commercial. They are carpenters, clerks, and commuters who cross the Elbe by ferry every morning, driving to jobs in Lüneberg or Hamburg, ninety minutes away. More than a few are out of work. Nobody tells them anything.

Which is not to suggest anyone here is unaware of what’s going on in the world in 2015. The people of Sumte are not hicks (or hinterwälder, as the Germans say). Word has reached Dirk Hammer, the bicycle repairman, and Walter Luck, the apiarist, about the capsizing trawlers, the panic in Lampedusa. Sumte’s mayor, Christian Fabel, has read in the Lüneburger Landeszeitung about the bivouacs at Austrian border towns. They watch the nightly news. They’ve heard of this crisis, the so-called Flüchtlingskrise. And they wonder where these people—more than a million migrants, displaced from the world’s bomb-cratered imbroglios and forsaken urban wastelands—are headed. The streetlights, a long-standing request now mysteriously granted, make them suspicious.

Only Reinhard Schlemmer watches the workmen and knows for sure. A grizzled figure with a wild nest of silver hair, Schlemmer lives on the far edge of town. He was once an officer in the National People’s Army but these days his voice is as soft as a low woodwind C. He’s retired, and to keep himself busy he sells roller trays and cans of primer out of the detached shed behind his house. He does it to chat with neighbors, keep himself informed. He may have lately fallen into the role of odd old man on the margins—the unreformed Communist with his cans of paint—but he was Sumte’s mayor when the border came down, a decorated Party member, and his bearing still suggests something of the phrase pillar of the community.

He remembers when, during those confusing years of reunification, all of the border villages came together and voted to rejoin the “kingdom”—meaning the Kingdom of Hannover, which was technically dissolved in 1866—from which the Cold War had cleaved them. People still used the term to refer to Lower Saxony, the West German state containing most of the kingdom’s historical territory. As mayor, Schlemmer spoke out against this idea. By joining Lower Saxony for what amounted to archaic feelings of feudal loyalty, he argued, they would forfeit the federal assistance earmarked for rebuilding the crumbling towns of the GDR. He said that unemployment would grip their forgotten border town, where most people worked for dissolving state-owned farm collectives. No one listened to him. They were a democracy now, and Schlemmer was able to enjoy one of the perverse pleasures of this form of government: the vindicated loss. It happened just as he predicted. People couldn’t find work and the towns along the East–West border continued with the business of slow decay.

With no federal revitalization money on the way, Schlemmer came up with a shrewd (which is to say capitalist) plan to save Sumte from extinction. He convinced a rich businessman in Hannover—the city, not the kingdom—to invest in the construction of a huge complex on the outskirts of Sumte, a private village-within-the-village where East German women would train to become caseworkers for a debt-collection agency. Thus would the area’s unemployed farm girls help lawyers cash in on private debts. And why not? If they were to embrace the market, they might as well embrace it fully. The office opened in 1994. At the ribbon cutting, a pastor admonished the town to “stand up for the stranger” before everyone started singing hymns.

The plan worked. For almost twenty years, the agency employed 250 women from the fly-bitten environs of Sumte and neighboring towns in Lower Saxony and Mecklenburg, becoming the area’s largest employer. But the 2008 financial crisis razed the debt market, and in 2012 the agency, now called Apontas, decided to consolidate its operations in Hannover. A few women, seduced by city life, moved with them. The rest lost their jobs. The complex has stood empty ever since.

Now Schlemmer thinks back to the moonless night a month ago when he’d been out in his yard, looking across the weedy lot at the polygon of blackness where the darkened Apontas buildings eclipsed a wedge of stars. The story of Sumte was the story of his life. Its failures were his. The investor who’d built the office complex had also planned to build a little chapel across the street from Schlemmer’s house, and Schlemmer could just make out the concrete and rebar of its unfinished foundations. He thought of that pitiful infant body lying in the Turkish surf. “All the children out in the dirt,” he remembers thinking. “And all of our halls standing empty.” He asked himself: What is to be done?

It’s an oddly warm October morning when Grit Richter, sitting in her modest office in Amt Neuhaus, gets a phone call from the interior ministry in Hannover. An administrator explains to her that Sumte, among the smallest of the thirty-six territories under Richter’s purview, will receive 1,000 asylum seekers starting at the end of the month, to be housed in the Apontas office complex. Richter isn’t sure she’s heard correctly. Yes, the administrator says, they know that Sumte is small. They also know that the complex is empty and disused. But the village has something that no other town in the area can boast: 21,000 square feet of dry shelter. Her options, she’s told, are to say “yes” or “yes.”

She hangs up. Like a lot of Germans, Richter is basically a Kantian: skeptical, pragmatic, stolid. When she moved to Amt Neuhaus to raise her children in the Elbe biosphäre (as tourist brochures advertise the area), she found a bucolic landscape that was bleeding people and work. She ran for mayor in 2011 and won. Apontas left the following year, but she’s since managed to bring a few jobs back to the area, increase child and elderly care, even find money for a few miles of paved bike lanes. Not much escapes her awareness among her 4,700 constituents living in border hamlets from Stiepelse to Wehnigen, but she can’t keep track of everything. She doesn’t yet know that Reinhard Schlemmer has been busy making phone calls of his own, offering up the Apontas complex and setting this new idea in motion.

The first thing Richter does is compose a nonchalant e-mail to a few choice associates, asking what they’re going to do to avoid a general panic. She requests their discretion, but it isn’t long before the news of a thousand refugees lands in Sumte like an albatross. Her phone starts ringing and doesn’t stop. She schedules an emergency meeting at the Hotel Hannover, Amt Neuhaus’s only inn.

Leaving her office that evening, she crosses the town square, where a bronze statue of Germania holds her sword unsheathed against Napoleon’s invading army of 1870. Beyond the statue is the old Communist-era hospital, now a superfluous and rarely open tourist center, and the Hannover Hotel, whose banquet hall is usually dark. She greets Angela Bagunk, the inn’s owner, and together they bore into the crowd.

The banquet hall is classic 1970s GDR, a mauve-and-faux-wood assemblage fit for a politburo confab, and not even Bagunk’s artfully placed yellow balloons do much to cheer it up. The fake flowers are sun-faded, the parquet is as worn as a roller rink. Just now the room is in chaos. Four hundred crowd-averse country people have crammed themselves inside, backed all the way to the foyer. They’re peering owlishly through the windows, bestriding the begonias.

Someone has also alerted the media, and Richter eyes without affection the journalists from several papers, national and international, who are pressed against the back doors, interviewing her constituents. The story, it seems, is a perfect metaphor for the crisis—1,000 refugees to 100 villagers, an overwhelming invasion—and Richter knows that the journalists are hoping to capture a panic. She walks to the stage and starts talking as calmly as she can.

Until the moment Richter received the phone call, the most contentious municipal issue Amt Neuhaus had ever faced was the proposed construction of a bridge across the wide and placid Elbe—a project that has united residents against the feckless local government since approximately the Franco–Prussian War. A bridge would shorten commute times and attract more investors. A bridge to replace the sluggish ferries at Darchau and Neu Bleckede could change everything for these dying towns. Now imagine that your mayor gathers the entire community into a cramped and crumbling East German banquet hall and announces that the federal government has ordered not the long-desired bridge, but a refugee camp, one that will require expensive renovations and result in myriad unknowns. The emotional valence in the room is not good.

At the back of the hall, two NPD agitators—nativists from the National Democratic Party, close to neo-Nazi on the political spectrum—unfurl a large germany for germans banner and heckle the crowd with cries of “asylum terror.” Other locals are quick to escort them out of the hall. There is no swell of support around here for the extreme right, no ochlocratic id in the form of NPD yard signs like there are in many neighboring towns. But it’s too late to keep the press away. Interviews with the extremists accompany most of the articles on Sumte in the days to come, including the New York Times, which quotes an ecstatic car-wash employee, local council member, and admirer of Hitler named Holger Niemann, who says he can’t wait for the asylum plan to implode and compel people to join his small but noisy coalition. “It is bad for the people but good for me,” he is quoted as saying, explaining to the reporter his theory of genetic heritage, according to which Germany is in danger of becoming a “grey mishmash.” Schlemmer flexes his GDR bona fides for the Times reporter, complaining that in the Communist era they would have simply stuck men like Niemann in prison.

Once the NPD men are gone, Richter distributes cold facts: The EU is taking on 5,000 new migrants every day, and is expected to have received at least 3 million by the end of 2017. Germany will have 800,000 new migrants by the end of this year, and it appears that most will be allowed to stay. Lower Saxony alone is already sitting on 18,000 rejected asylum applications, of which 80 percent are expected to receive “tolerated” status. There are tough decisions to be made in every town in Germany and this much has been settled for them: The building complex in Sumte will be leased for one year to the Workers’ Samaritan Federation (ASB), a private nonpartisan charity that specializes in disaster relief. Maximum occupancy will be maintained throughout the year. They’ll all regroup and reassess next October.

Jens Meier, director of the regional ASB office, steps up to the podium. Meier is a warm, lumbering keg of a man, at least 250 pounds and a lot of it the sort of nonsense-free muscle earned by hauling sandbags and wood pallets alongside his subordinates. ASB runs dozens of relief programs in Germany and abroad, and just a glance at Meier makes it clear that there can be nothing amateur or florid or evangelical about any of them. This will be a warm-bed-and-potatoes affair. A sober, serious mission. He tells the crowd that he will permit no mischief in the Sumte camp, no graffiti or midnight Molotov cocktails. They’re going to hire Arabic-speaking guards and set up perimeter fences. The residents will be free to come and go as they please, but townsfolk will need an invitation to enter. It’s an isolating tactic, but a necessary one, he says. The asylum seekers, who will soon arrive from Syria, Albania, Sudan—eighteen beleaguered countries in all—must be protected. But there’s good news, too, he says. There will be somewhere between sixty and eighty job openings at the camp, from janitors to German instructors.

The people are not placated. “I have two daughters,” a woman says. “How can I protect them?” “These young men have needs, don’t they?” another asks. Others want to know about the doctors’ offices and kindergartens in Amt Neuhaus. Will they be overrun? There’s no police station closer than Lauenburg, twenty miles away—what if there’s a sudden mob? An assault? Even the plumbing in Sumte will need to be overhauled, to say nothing of the infrastructure of integration: the job centers and democracy-loving mosques that politicians seem to expect will emerge fully formed from their wheat fields and pastures. Still others are worried about the safety of the refugees themselves. Dirk Hammer, the bicycle-maker and handyman who sits front and center at the meeting in a crisp gingham shirt, says he’s sick to his stomach with the thought of what could happen, not just in Sumte but throughout Germany, if the far right organizes against refugees. Not even Meier’s cast-iron security will suffice, he says. Hammer was one of the first to phone Richter when word got out. His family has lived in Sumte for 400 years.

Within a few days, Richter convinces the ministers in Hannover to reduce the number of refugees from 1,000 to 750, claiming that the sewage system in Sumte will be unable to handle the sudden increase in wastewater. As of yet there is no talk of integration. First things first: Get the lights on, install new pumps. Throw up some fences. The journalists report that there will soon be seven refugees to each villager in Sumte. Sieben zu eins becomes a viral catchphrase to describe fears of a nation overrun by impecunious foreigners. One columnist describes Sumte’s residents as the begrudging yardsticks of willkommenskultur, the culture of openness that Germany has articulated for itself in response to the preceding century of geopolitical insanity. “The whole world is watching,” he says. And for a few weeks, he’s right.

Germany ratified its current constitution, or Basic Law, in 1949, as the country lay in ruins of its own design, quartered and controlled by Allied powers. Constitutions tend to reflect the conditions under which they were drafted. Just as the US Constitution seems preoccupied with colonial tyranny, the Grundgesatz is concerned with the threat of dictatorship and the plain, unambiguous assertion of human rights. The first sentence of its first article reads, in its entirety, “Human dignity shall be inviolable.” Its creators even added a clause enshrining the right to asylum for persons escaping political persecution. This is an oddity in the genre of nations’ founding documents, which do not typically grant rights to noncitizens at all. But the line did not provoke any real controversy when it was written, and it was soon supplemented by protections established during the UN’s 1951 Refugee Convention in Geneva, and later expanded with the 1967 amendments. In 1992, during a wave of migration following the collapse of the Soviet Union, Germany’s parliament voted to restrict this previously unqualified right to asylum, but the clause remained in place, and the UN continued to affirm the rights of asylum seekers to find safe harbor “without discrimination as to race, religion or country of origin.”

Then, two years ago, more than a million asylum seekers crossed into Europe, and the UN had no idea what to do. The world’s displaced had been steadily growing in number for years, increasing by more than 50 percent since 2011 as crisis begat crisis. By the start of 2015, there were more displaced people than at any time since the Second World War. Most of the externally displaced found refuge in other impoverished countries, as is nearly always the case; just 4 percent made it into any part of the European Union. It was still the largest migration into Europe since the fall of the Iron Curtain.

Among the refugees, half came from Syria, Afghanistan, and Somalia. Wherever their origin, many of those who came were Muslim; even more were dark-skinned and male. Many hoped to reach Denmark or Sweden, chasing rumors of jobs and welfare in Scandinavia, although most didn’t make it that far, since EU authorities registered them in whatever country they appeared without papers. (“They caught me on the bus to Copenhagen,” one friend from Aleppo, who has since settled in Cologne, told me. “They were very nice about it.”) They had heard tales of gold-paved boulevards and seen footage of refugees being welcomed with balloons and care packages. In this sense, they were victims of an epidemic of migratory misperception and fantasy—spread via cheap, prepaid smartphones—that would have stunned anyone from the age of Ellis Island. Following a fable cultivated in equal parts by Mediterranean smugglers and social media, they came, leaving a subaltern miasma of disintegrating states, war, drought, persecution, and entrenched post-Soviet misery. And when they got to Western Europe they learned their condition had a name: the refugee crisis.

And the Germans reflected on their constitutional duty.

This was in August 2015, long before the rise of Donald J. Trump and the resurgence of a strain of nativist populism within Germany of which Pegida, the “Patriotic Europeans against the Islamization of the West” movement, was for a few months the most visible sign. (Pegida supporters have since rallied around a new organization: Alternative for Germany, an increasingly powerful far-right political party.) It was before all that, back when 100,000 people stood at the closed Hungarian border. The mood was sufficiently humanitarian in those days that Germany’s chancellor, Angela Merkel, felt compelled to utter three now-infamous words: Wir schaffen das. We’ll manage it, or even, simply, we’ll do it. Meaning: we’ll take them. We’ll suspend the Dublin Regulation and accept any legitimate political refugees who can reach us. We’ll house them in gymnasiums, old apartment blocks, hotels, barracks, rectories—anywhere we can find.

The words marked the beginning of a new kind of civic experiment. Countries do not always, or even very often, practice the ideals one finds etched here and there into granite plinths around their capital cities, invisible to all save the schoolchildren who have been made to memorize them, but now Germany was actually going to try to uphold the spirit of its sixty-year-old constitution, with its singular concern for human dignity. They would kick the tires on an untested idea: that a wealthy country might extend its protections to deeply foreign populations at significant cost, simply because the tenets of liberalism demanded it. Even in America, the land of immigrants, we have never risked it. (Americans have always been suspicious of refugees. We reserve our trust for the prosperous.) I was living in Berlin at the time and among my leftist groups of international friends, Merkel’s words felt like nothing short of a full-scale rewiring of the modern nation-state, which since its origins in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries has always involved certain assumptions of ethnic solidarity. This new openness felt unprecedented.

Some saw Germany’s stance as an attempt to make a kind of ultimate atonement for historical sins: a radical penance underwritten by the guiltiest country in the modern world. But to actually revisit the summer of 2015 is to remember that Germany did not plan to act by itself. All members of the European Union were expected to uphold the commitments to international asylum to which they’d agreed. The EU briefly considered penalizing countries that refused to accept their “share” of refugees, a figure that would be determined by host population and GDP. Merkel also defiantly predicted that wealthy, cosmopolitan countries such as Canada and the United States would take seriously the phrases written in their own founding documents and on the plaques of their harbor statues, opening their doors a little wider to these needful, these tired, these war-ravaged poor. It didn’t happen. A handful of rich countries with small populations—Sweden, Switzerland, Austria, the Netherlands, and Denmark—did resettle comparatively large numbers of refugees. Otherwise, except for a paltry few thousand in France and Italy, and the 10,000 Syrians per year that President Obama added to the United States’ modest annual intake, none of it happened. Germany stood alone.

Winter

Dusky figures in anoraks, walking through the slop of fallow fields with cell phones high in the air. Pursuing the aura of connectivity. But there’s no signal to be found, and no broadband in the whole region, though rumor has it that cables will finally come through Amt Neuhaus in 2018. The locals use USB sticks to link their computers to a plodding Vodaphone 3G network. The arrival of the first hundred phone-toting refugees, each anxious to Skype with families back home—every migrant, no matter how remote his or her point of origin, is fluent in Skype and WhatsApp—has knotted the network in such a way that nobody in either town can get online at all.

But who are they? Newcomers step off the buses and vanish into the fenced-off camp. The four or five families who live within sight of the complex watch the arrivals with interest, but there is no place in Sumte where they might have a social encounter, so what they know is provisional and unverified. “There are apparently a lot of families,” one neighbor tells me. When it’s warm out, kids emerge from the camp and kick a soccer ball around the freshly weeded parking lot. Their shouts are heard in abutting fields. More often, the villagers see them on the move. It’s two miles from Sumte to Amt Neuhaus, and the confusing local bus system makes just three trips a day, two before 7 a.m. and the third before 9. Most of the refugees walk two by two through the village and along the roadside bike path to Amt Neuhaus in order to visit the nearest supermarket, trudging past barren fields, carrying grocery sacks and tote bags, if not quite bindles, yet still offering for any lingering journalists a satisfying tableau of biblical exodus.

There’s an air of sullenness that informs photographs of this pilgrimage to Amt Neuhaus. But up close the mood seems closer to bewilderment. They seem to be wondering: Will we be allowed to stay? To work? What sort of place is this? A parking lot on the edge of town serves as the bus stop, and here I meet a family from Afghanistan—a father, a mother, two children, and aunties and grandmas toting supermarket bags. With an artful combination of German, English, and hand signals, the father indicates that he doesn’t understand the bus schedule, and I likewise indicate that I’m happy to help. We examine the display. It’s incomprehensible. Some bizarre shorthand is being used to indicate on which days the bus is on a holiday or half-day schedule according to the local school system, and I can’t decipher any part of it. Then I notice that the schedule expired six months ago and is no longer valid anyway. I try to explain. The father and I make goofy grins at each other. It’s an exaggerated friendliness, born of muteness, which all foreigners know.

It’s hard to imagine congeniality alone will help these newcomers. The main concern in Sumte seems to be theft or break-in. One loyal husband is caught by a reporter erecting motion-sensitive lamps along the trusses of his half-timber house—at the behest of his wife, he claims. Another farmhouse adds the unusual sight in patriotism-averse Germany of a German flag above the doorstep. Its anonymous owner (or possibly a neighbor) is quoted by another paper: “I don’t see why we should have to take in these numbers. It won’t work. There is nothing for them here.” In Amt Neuhaus the supermarket hires extra security to patrol aisles that once saw a few dozen visitors a day, but which are now bustling. In the first weeks, I’m told, the guards catch several shoplifting German grandmothers, but no refugees.

Walter Luck, the apiarist, is more trusting. Luck and his wife live on the opposite side of Sumte from Schlemmer and the camp, and their living-room window looks directly onto the start of the bike path to Amt Neuhaus. They have a perfect view of the parade to and from town. The Lucks supplement their pensions with a terra-cotta-roofed honey stand outside their house, which brings in a few euros each week through the cash lockbox they’ve set out next to a grocer’s pyramid of hive-fresh honey in three varieties. They adhere to an honor system. The video camera screwed to the stand’s upper joist appears to have been installed during the height of Stasi paranoia, and is impressively rusted. You can tell the couple is quietly proud that they’ve continued to stock honey outside where anyone might steal it, even as some neighbors install new locks and motion sensors. But Luck’s wife declines to say much when I ask about the refugees, just that they haven’t talked to any of them and simply wave from a distance. “I don’t want to say anything about all that,” she tells me. “We don’t interact much. We just see them walking down the road.”

“We say hello, they say hello back,” Walter adds, returning from the hives. I try to endear myself by buying several jars of honey. But he doesn’t want to share anything else. I ask whether he’s sure, in response to which he springs into the air with shocking youthfulness and yelps. I apologize, thinking that either the refugees or I have driven him to this bizarre apoplexy, but he only reaches into his sweater and pulls out a dead bee.

“Happens all the time,” he says, and flicks it away.

By December 2015, Sumte’s population has tripled—102 citizens, 229 displaced and stateless guests. Asylum seekers are streaming into Germany via the opened land route through Macedonia and Hungary, up through Austria, and those assigned to the camp in Sumte continue to arrive daily by the busload.

An Advent concert at St. Mary’s, the Protestant church in Amt Neuhaus, offers the first opportunity for comingling. Villagers and refugees pack into the old brick church to listen to an evening of carols and hymns, and to satisfy their mutual curiosity. Near the end of the night, seventy well-rehearsed, mostly Syrian children rise to sing “O Tannenbaum,” and for a moment there can be no argument about the goodness of what’s being done here.

Behind the scenes, Jens Meier is the busiest man in Lower Saxony. “I’m working like an American,” he jokes. He’d had just eight workers at the start of the renovations, but he’s since poached fourteen from another camp to build bedrooms and a health center. The washrooms aren’t finished, either, and insomniac villagers catch glimpses through lace curtains of Meier’s employees driving the camp residents late at night to Amt Neuhaus, where the fitness center has donated its hot water after business hours. One evening, more than 400 people are chauffeured to the gym, minivan by minivan, and the showers flow until dawn. A sign on the community bulletin board in Sumte advertises openings for nurses, cleaning crews, drivers, caretakers, tutors, and social workers. Some refugee camps rely on catering services, but Meier insists that this camp make its own food, so he’s also in the process of hiring a kitchen crew. “It’s like in the old days when a ship would travel from Europe to America,” he says. “You need a good cook!” The ship metaphor is a useful one. The camp is isolated, filled with strangers from eighteen different countries pressed together by circumstance, and it will survive only by dint of its captain. By the end of the month he’s staffed his kitchen with sixteen workers and the line for dinner stretches down the long main hall.

Aside from Meier’s motion-blurred bulk, the most visible figures that winter are dozens of teenagers, who move through town in a vaguely threatening cloud of pubescence. They’re restless. There is no school save the overstuffed and optional German classes held in the camp, and their days pass in unstructured idleness. It’s clear that before long a scandal will occur, and one evening a group of boys and young men walk the two miles to the supermarket in Amt Neuhaus, where they buy a few bottles of liquor. There is no drinking in the camp itself, nor any smoking—Meier’s laws are absolute—so back in Sumte they park themselves at the derelict concrete bus stop on Hauptstraße. There the boys do what boys do in cramped bus stop hutches, and in the morning all the bottles, cigarette butts, and generous blazons of vomit are discovered by the village children on their way to school.

Not exactly mob or murder, but it’s a piquant enough event to ride the latticework of gossip that connects village to village along the Elbe, and the news soon reaches mayors Richter and Fabel. Meier is phoned. He learns who is responsible (“I would not have wanted to be in that interrogation room,” one villager tells me), and by nightfall the boys have dutifully snapped on latex gloves and are cleaning up the bus stop with mops and brooms. For the next few weeks, the people of Sumte speak of little else.

“They bought the Polish vodka and the Russian vodka,” Schlemmer tells me. The whole thing is amusing to him. “I always thought that Arabs don’t drink. But when one is just starting to drink, heidewitzka!” He laughs.

All but the sourest villager agree that the event is a clear victory for Meier, who by acting swiftly and with paternal firmness seems to have proven something important about the whole endeavor. “It’s all right now, Jens cleaned it all up,” one shy housepainter (I’ll call him Thomas) tells me, and from that day forward I can’t find anyone willing to utter a harsh or even ambivalent word against the ASB chief. He has proven himself. Meier also sets up a teen center in an empty wing of the camp that once housed the collection agency’s vast data archives, transforming the antiseptic chamber into a recreation hall with ping pong tables and a rink for skateboarders, after which all incidents of roosterish adolescent enmity seem to subside. “We’re learning as we go,” he says, pleased.

By Christmas the camp hallways echo with the polyglot cries of 189 children. They shout, they wail, they sing “O Tannenbaum” ad nauseam. Outside the camp, extended families come home for the holidays. Sparklers, bottle rockets, and flutes of sekt herald the new.

A few weeks later, I travel to the camp from Berlin by public transportation. I want to approximate, however roughly, the experience of a refugee making his or her way to a new home. In a rental car the journey is a long but pleasant route through oak groves and beneath old brick belfries. By train you have to overshoot the village by fifty miles and backtrack from Hamburg. There are multiple transfers. The trip lasts six hours. The world itself seems to be decelerating as I transfer from a high-speed to a regional train, then to a city bus and finally a country bus filled with ruddy schoolchildren. The earth outside is undistinguished green mud. Even with my credit cards and passable German, even with the privileges of a US passport, I feel a little trapped here on this strange bus, miles from anywhere. As we near the village, plywood figures appear to push empty strollers into the road—a scarecrow technology that works only on out-of-towners. The driver doesn’t even tap the brakes.

On the bus, until my signal drops, I scroll through reports about the mass sexual assaults at New Year’s Eve celebrations in Cologne. By now the eyewitness accounts have given way to right-wing demagoguery. The perpetrators, it is believed, included several refugees, or if not refugees at least Muslims—at the moment, no one seems sure. Although the attack is an anomaly, and although most of the refugees have been peaceful and law-abiding, the national mood toward Merkel’s asylum politics has curdled. Opinion polls rapidly invert. Alternative for Germany agitates for the removal of refugees and the closing of borders. There commences a quiet epidemic of defacement and destruction of asylum shelters—including one arson attack every three days across Germany—which police seem unable to stop. In most cases they can’t even find a suspect.

The bus drops me off on the edge of Amt Neuhaus. Chicken coops are quaggy with snowmelt. I leave my things at the Hannover Hotel and stop in at the town hall to see Richter, who is her usual unflappable self. The most pressing issue, she tells me, is to teach the arrivals German so that they might have a chance on the job market. This seems a little premature. Has there been much integration between the towns and the camp? Are there any plans or programs to help them understand the German job market? What jobs are even available? “You’ll have to ask Jens about that,” she says. “He’s more involved. There are many nice things he can talk about.”

It’s clear and not too cold on the way to Sumte the following morning. On either side of the bike path, rain has pressed Arabic-language pamphlets into the earth. Some of these turn out to be cultural guides. They include tips that range from the instructive—“People in Germany value their personal space and privacy, so they can sometimes appear distant”—to the dubiously intentioned: “Urinating in public is an offense and is not allowed”; “Cutlery is usually used when eating at a table.” In the distance I see two men, a skeleton TV-news crew, setting up a tripod for a well-framed shot of the middle of nowhere. They’re the last of the media to leave. Post-Cologne, stories like Sumte’s have become quaint.

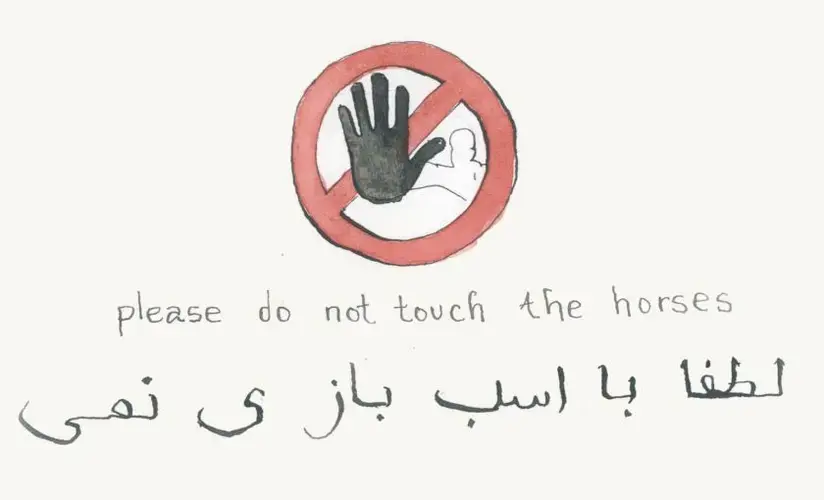

At last I reach the misty village. Everything from the tree stumps to the tool sheds is lichen-touched. One old woman peers down at me through the ox-eye window of a mossy gambrel roof. Except for a garage where someone has kenneled what sounds like dozens of hunting dogs, the town is utterly silent. You’d never guess that the camp has reached peak capacity, with 754 refugees alongside about sixty employees. The villagers’ attitudes toward the camp manifest in strange ways. The horse farm across the street has posted signs in German, Arabic, and English asking passersby to please not touch the Arabians. I call out to a man I’ve decided must be the farm owner, but he waves me away. People are sick of journalists. Dirk Hammer, the bicycle man, has told me they’re unhappy that they’ve been portrayed as racists, when the truth, he says, “is that we’re simply concerned.” Some take note when the district police car from Lauenburg is parked outside, a sure sign, they believe, of another scuffle between grown men, one of whom can’t abide the other’s nation or faith. There are occasional fights—always catalyzed by alcohol, Meier says—but months later, on my last visit to Sumte, a guard will tell me that the camp is by far the most amiable of the four or five he’s worked at. Most often the police come by to enjoy a cup of coffee, which a camp secretary offers me as soon as I walk in the door.

The main hall of the camp is alive with all the vital energies of the dispossessed. People have nothing to do here but practice their German and gather in the halls with cups of red tea, dispensed from a giant samovar sitting on the folding table of an ad hoc café. I find Meier. He says he’d still like more help but there haven’t been many volunteers from the village. I ask how many exactly. “I’d say it’s about sefr,” he laughs. Sefr is Arabic for zero. Among those who are helping out is Hammer, who has been collecting disused bicycles and fixing them for the camp residents. “I’ve made a few acquaintances here,” Hammer confesses later, as though I’ve caught him being naughty. “But it’s not like you know them very well. It’s like with other people in the village. You just say hello.”

I say hello, too, introducing myself to a few of the young men loitering in the main hall. They hail from Iraq, Syria, Palestine. They gesture to their sleeping quarters inside one of the attached warehouses, a vast warren of semiprivate cells.

Amt Neuhaus looks all the sleepier after my misty walk back into town. I sit down with a coffee and the local newspaper inside the empty bakery. There’s been an arson attack on a forty-eight-bed refugee camp in Barsinghausen, near Hannover. Back at the hotel, the TV news airs a segment on other arson attacks that followed a Pegida demonstration in Dresden. Meier’s anxiety about saftey seems justified.

Yet the isolation in the camp feels extreme, especially in the middle of winter. There can be no neighborly drop-ins from the village next door. Camp residents must show guards a badge to come and go. The complex itself is improvised and strange, a shelter that never quite manages to become a home. Families can’t cook dinner together or cuddle in quiet repose. They must make do with their assigned “bedrooms,” a generous euphemism for the jaundiced mattresses and flimsy plastic room dividers each family enjoys. Although Meier is anxious that the camp not resemble some wintry Bantustan, he can’t force a community into existence. He is happiest when the residents transform the camp for their own use. When a trilingual Moroccan named Abo has the idea to open a shisha bar inside the camp, Meier relaxes his prohibition against smoking for the sake of general camaraderie. For weeks thereafter, wafts of pomegranate and strawberry trace a breezy scent from the front of the complex as far away as Schlemmer’s living room.

Schlemmer may be the only person in town who remains excited about the camp and its promise of a renewed Germany. He has embraced Merkel’s optimism, even if he occasionally fears that her lack of concrete planning may have created a bit of a pflaume, or plum of a situation, at the national level. From his vantage next door he bears witness to the lives they’ve already saved. The buses have been offloading passengers at his doorstep to avoid getting caught in the tight roundabout at the camp gate. He makes sure to greet every disembarking soul. Some of them—the Africans, whom he calls neger, a politically incorrect term—are blacker than his blackest paint, he says, “so black their eyes glow in the dark.” Some, he learns, are doctors, engineers, scientists. Whoever they are, he’s happy they’re here, and when he discusses the issue he seems to beam with pleasure. We need young workers, he says. “Otherwise the whole country will turn into a senior city.” He is amazed that some of the mothers arrive shepherding seven, eight, even nine children. For centuries, the peasants of Europe measured their affluence in children, and now Schlemmer looks at these families and sees the precious sum of their wealth. Little spatzen, he says. Little sparrows. No, he corrects himself. Little black-haired organ pipes, each a different height.

Spring

We forget how weather shapes the world. Winter presses strangers together. Desires shrink in darkness. But as the days get longer, meadows and paddocks come back from the dead. New plans replace the anxieties of winter. The refugees begin to venture out beyond the confines of the camp—in some cases leaving Sumte altogether. At first it’s just a handful of young men in February and early March. It doesn’t seem to bother the locals, most of whom are occupied during my next visit with the business of Easter.

On Holy Saturday morning I talk to Thomas, the shy housepainter, out in his driveway on the bridle path. A family feast is about to begin. He still hasn’t had much contact with the refugees. He sees them walking down Hauptstraße on their way to town. They seem—how to put it—“a little embarrassed.” Maybe that’s why they don’t make more of an effort. His wife has tried to visit the camp to volunteer, but the ASB guards are unfriendly and gruff. Some of them can barely speak German. “It scares people off,” he says. “It’s like there are two towns living side by side.”

In Amt Neuhaus, Renate Schieferdecker is preparing her sermon. She shares a pastorship with her husband, Matthias. Between the two of them they’re holding an early service at St. Mary’s in Amt Neuhaus, another in Stapel, and, the following day, a third in Konau before she drives back to St. Mary’s for an Easter Monday trombone concert. Rural towns in Germany no longer have the population to support a pastor in every rectory. The ordained are spread across multiple churches, some of whose cornerstones predate the Great Northern War. The Schieferdeckers manage eight Lutheran parishes of dwindling and white-haired memberships.

I suggest to Schieferdecker that the arrival of so many new residents must have seemed like a unique opportunity to draw more souls into the Christian fold. She looks at me like I’m crazy. “We were naturally concerned when the news came,” she says. Most of the worries concerned the financial burden on the town, including what she describes as “social-assistance envy.” And then there was the culture shock. She confides that she’s heard about some problems with Western-style washrooms (“Muslims have to wash several times a day, and they were getting water everywhere”), and with what she describes as Afghan-Persian infighting (“Any time you get an Afghan and a Persian together, there will be conflict”).

Schieferdecker’s breathing is heavy and sharp even though we’re just sitting in her rectory office drinking coffee. She comes from a small village in the Harz Mountains, and this Dutch-like lowland town does not seem to agree with her. But her assigned parish is God’s will. So, it seems, is the refugees’ presence. Like everyone else, she praises Meier and ASB for handling things wonderfully.

Fire pits roil on Holy Saturday night. The conflagration beyond the bus station in Amt Neuhaus is so large it smolders for three days. Not many refugees attend. A few wander out to the volunteer firehouse in Sumte, where locals have gathered around a smaller fire, but most stay in the camp.

On Monday afternoon, a brass band unpacks trombones and trumpets in the church transept. About twenty churchgoers show up to hear the musicians blurt their way through a half hour of hymns with appreciable enthusiasm, if not much skill. The last arrivals are four Iranian men in their early twenties. One is awkwardly overdressed in a powder-blue suit. They sit in the last pew and don’t talk to anyone. Most Iranians are not long in Amt Neuhaus once they learn of the diaspora in Hamburg.

It’s hard to say how many refugees are left, Meier tells me—“a few hundred less than capacity.” He can’t stop them from leaving. Between the isolation and the shock of the frigid German winter, he says, the unmarried men, in particular, became despondent. The desire to leave outweighs their monthly stipend. Some knock on Schlemmer’s door to ask, in admirable if choppy German (only the children have, almost without exception, achieved fast fluency), how to reach Sweden or Hamburg. Helpful even in the face of failure, Schlemmer dispenses bus schedules. He doesn’t want anyone to get lost. But others just start walking, along the road or straight into a field. Before they leave they sometimes bare their souls to Meier, and in doing so they sound an awful lot like Sumte’s NPD pariahs: “There’s nothing here for a foreigner,” they say. No jobs, no opportunities, and—not a small matter—no way to meet women. Even Abo leaves, and without him the shisha bar closes.

“Yes,” Schieferdecker says after the concert, “the refugees are leaving.” In previous months, a handful of curious Muslims would stop by the church each week. She shows me Arabic and English versions of the parable of the sower she’d had typed up and printed. But now no one comes, and there are just four men left of the five or six Iranian families who’d briefly joined the church. “They consider themselves Christian,” she says. The man I’d seen wearing the suit has delayed his departure because he’s learning to play the church’s pipe organ, but even this diversion won’t hold him here forever. There’s been an evacuation. “Some of the refugees walk fifty kilometers to the nearest train station,” Schieferdecker says. Others walk even farther. One man from Darfur, who’d been living with a local family, disappeared a few weeks ago and was eventually picked up by the police at the French border, having walked a distance of 370 miles toward contacts in Paris. The police returned him to Amt Neuhaus, his registered home.

Four countries—Croatia, Serbia, Slovenia, and Macedonia—close their borders in March in response to the 123,000 migrants who landed in Greece at the start of 2016. This impasse slows the inflow of migrants to a trickle. There is no great outcry in Germany, where last autumn’s optimism has been replaced by the rise of populist parties and media reports, rarely impartial, of migrant crimes. Merkel’s Wir schaffen das has grown an ever-lengthening tail of asterisks, footnotes, and notas bene.

The EU-Turkey Refugee Agreement, also signed in March, will send to Turkey tens of thousands of the migrants trapped in Greece, in return for which Germany will accept some of Turkey’s Syrians. Turkey will also receive 6 billion euros in EU funds. It is not clear whether the agreement violates EU asylum laws, but few politicians now seem concerned with such formalities. Germany is busy developing legal maneuvers to deport some African and Afghan asylum seekers without violating the UN prohibition against refoulment. In April, Obama praises Merkel for being “on the right side of history.”

All spring long, in the world beyond Sumte, profiles of refugees appear in international papers. They’re almost interchangeable, these action-packed accounts of harrowing journeys to Europe. I read dozens of them and even write one or two myself. I notice that most stories of asylum by Western journalists fall into the same trap of condescension: flattening their subjects into simple creatures of suffering and good intention. They want a roof, a job. They love Europe and democracy. They suffer nobly at the hands of German bureaucrats.

If it is a dehumanizing lie to suggest that all refugees are criminals, as the right-wing press seems content to do, it is no less a lie to depict them as hapless victims. My own experiences suggest that refugees are as diverse as any other randomly assembled group of people. Between visits to Sumte I meet dozens of them while volunteering at an English-language class for refugees in Berlin, and while visiting other camps and activist groups around the country.

I meet and profile for a magazine a Syrian rapper from Aleppo who stands in awe of Run-DMC and Eminem, and who lives in a city on the Baltic coast. He’s lonely and depressed. He’s also a devout Muslim and writes anti-gay screeds on his public Facebook news feed, but when my photographer calls him out on his bigotry, my profile subject seems truly hurt. They have a chat about tolerance in the West, and later he tells me—without a trace of dissembling—that he’s reformed his opinions. He’s a European now.

I befriend a committed Marxist from Tartus, Syria. He is not an asylum seeker but a student. He holds a master’s in political science from an Italian university, and we spend late nights conversing about solidarity, the indignity of asylum, the politics of America and Israel, and other light subjects for smoky rooms. I offer to help translate an Arabic statement for one of his rallies in Berlin—a document that makes several uncompromising demands on the German government—and through a drunken misunderstanding end up agreeing to perform the speech myself, in freezing weather, during a march of Arabs down Kottbusser Damm. Beforehand, I tell him that I’m a little uncomfortable with this breach of journalistic objectivity. “Don’t worry,” he tells me. “You’ll do great.”

Another Syrian, a former revolutionary from Aleppo, also becomes a dear friend. My wife and I attend regular parties at his palatial apartment near the city’s red-light district, a flat he shares with other Arabs and Australian and Irish expats. The parties are more libertine than I’m used to, but they always include heaps of Syrian food. My friend is an accomplished chef. His parents, who were once wealthy industrialists, are still living in a refugee camp outside the city after more than two years in Berlin. They haven’t yet been able to find an apartment close to their daughter and her growing family.

I meet a seventeen-year-old boy from Afghanistan who speaks no English but is a ranked chess player and, based on what I’m able to gather from his friends, an academic prodigy. He has one college degree and has been accepted into a German university for his second. He is paralyzed by shyness.

These people would make good profile subjects, which is to say they aren’t the ones Germans—some Germans—are afraid of. Occasionally, I meet one of those. For a few weeks, at the language class, I teach English to a man from Libya who cannot bring himself to take instruction from any of the female volunteers or even shake a woman’s hand. He just smiles and shakes his head.

Other men at the volunteer program, though more willing to integrate, nonetheless fail to improve their English or German, even after several months of instruction. How can they hope to find work here?

I’m not sure it’s possible to tell any of these stories plainly, with open heart and without agenda. I wonder how much good it would do anyway. Everyone I talk to seems to have already made a decision about the “refugee question”: whether to open borders completely—No borders! No nations!—or close them to the masses of false refugees, secret terrorists, and “economic migrants” who, according to politicians on the right, make up the majority of asylum seekers. It strikes me that if what Germany is trying to do is ever going to work, it will depend not on the purity or suffering of the migrants—where the media has chosen to rest its sights—but on the beliefs, prejudices, and fears of their hosts.

Summer

Europe has never been free of mass migratory movements. During the German ostsiedlung, or eastward expansion, thousands of settlers wandered into the hinterlands of the Holy Roman Empire. Sumte was founded in this medieval era, when settlers crossed the Elbe to cohabitate with Slavic farmers living on the far bank. There were no passports. Migrant laborers followed rumors of good farmland and ready work. Only in 1866, when Hannover became a province of Prussia and its long line of Hohenzollerns, did Sumte find itself part of a country we might recognize as modern, with settled notions of citizenship and nationhood. Sumte passed from Prussian hands to the Kaiser, then to Hitler, the British occupation zone, and Soviet control. When the GDR was formed, watchtowers went up and a three-mile-wide exclusion zone incorporated all Elbe border towns. Those who lived in Sumte could not enter or leave the village without a permit. Family visits had to be requested in advance.

Taking this long view, the refugee camp is just one more radical change to befall the village. If history is any judge, it will eventually be replaced by something else. By the start of summer, only a handful of people seem to think the camp could become something more permanent—something to pull Sumte out of the mighty historical entropy in which it seems permanently gripped.

One of those people is Meier, who by May has corrected most of the shortcomings that had troubled the camp in its first months. The internet works. There is a fine canteen, not to mention a laundry service, shuttles to Amt Neuhaus, the teen center, schoolrooms, a cell-phone store, a medical center, therapists’ offices—even a movie night whose programming is determined by a committee of resident mothers. (“They insisted that it should all be in German,” Meier says. It’s the first cinema Sumte has ever had.)

He has more time to improve the camp now that so few residents are left to care for. Into the summer, more and more people leave of their own accord, not just men now but couples and families. Just eighty residents remain, mostly families with young children. The hallways are hushed.

“If only we’d had internet from the very start,” Meier laments, then people wouldn’t have left so quickly. They might have stuck around, learned the language, found some work.

But the internet issue is only a synecdoche for the larger political boondoggle. Germany’s position on asylum is more incoherent than ever. Thousands of asylum seekers are stuck in Greece, where they await EU translators and caseworkers who may never come. Merkel is facing unprecedentedly low approval numbers into the summer. It doesn’t seem to matter that the country’s borders, as Meier is quick to point out, have been effectively sealed.

I ask Meier whether he thinks they’ll continue to accept any new refugees. He takes a while to respond, and when he does it is with what seems like a non sequitur. He tells me he often thinks about Alberta. Have I heard of it?

We’re sitting in his office in the Sumte camp, which is predictably utilitarian. The only window looks out on another window. On the door someone has taped a piece of paper that reads big boss. Meier lives in Hannover but he eschews urban life and often finds himself thinking about Alberta, that pristine Canadian landscape. He has misty dreams of Alberta, he says. He also thinks about statistics. “My religion,” he often says, “is mathematics.” He thinks about the fact that there are sixty-two people on the planet as rich as the poorest 3.5 billion. (It is now thought that eight people control as much wealth as the poorest half of the world.) He thinks of monopolies, vast collections of power and money, selfishly hoarded. The oil sands of Alberta, he says, are often on his mind. Shale-mining operations that cover an area the size of England. Ten thousand new wells since 2008, he says, both fracking and horizontal drilling.

The First Nations people of Canada live there, he says, and I realize he may have rehearsed this monologue for just such an occasion. “The Canadian government offers them money, but they don’t want money,” he says. They want to live in an unspoiled landscape. They want to live at home. And this—this—is what people want all over the world: to stay at home, to continue to have a home. “So now politicians in Europe have closed the borders,” he booms. Merkel has made her deal with Turkey. There are no more asylum seekers coming through Idomeni, they’re being shipped to God knows where in Turkey, yet none of the problems that created these mass movements of people in the first place have been solved. Assad continues to bomb his own citizens with impunity, he says. Afghanistan and Iraq are fracturing. In Africa, 66 percent of the land is hot, dry desert. We could be planting trees and irrigating wide swaths of the country. Instead, we’re destroying it: in Alberta, in Africa. “These are big problems,” he says. “Our families here come from war, they come from total poverty.” This is the world Meier is responding to: the world’s 65 million uprooted. The average period of displacement is seventeen years—a generation lost at sea.

“So indeed, to answer your question,” Meier says, “it may be that we’ll get more refugees. If the minister calls me tomorrow and says, ‘Mr. Meier, you must take hundreds more,’ it’s no problem. We’ll see what happens this summer. But we’re ready: The camp, the town, everyone is ready. If the refugees can only get here, we’ll take them. We’ll take them all.”

In September the trees, previously leafy and undulant in the lowland winds, are suddenly heavy—with pears, with apples, with powdery plums. It’s the season of mellow fruitfulness. Those lining the main avenue drop their bounty into the harvested fields on either side of the road, to rot in the troughs of manure and straw.

I’m driving around the countryside in a rental. A mile outside the village, a boy is playing in a plowed field, and I park to watch him. He mounts a three-deep stack of hay bales and performs a tight front flip onto the unpacked hay beneath. Could you do that again? “I can do this all day,” he says, and obliges. We’re the only people in sight.

A storm has passed over Sumte and the light is honeyed. At the camp a belated sign has appeared outside the front entrance: herzlich wilkommen. Through the fabric it’s easy to make out the more apposite text facing the building’s doors: auf wiedersehen.

The refugees are gone. The last seven holdouts left last week for other camps, for Hamburg—anywhere else. About eighty have settled around Amt Neuhaus in Soviet-era apartment blocks, but the rest have left. It wasn’t by local choice. There are huge political weather patterns at play here, and they buffet and bedevil ships like the Sumte camp without ceremony. And the labor that went into the camp? The tax dollars? The discussion and compromise? It feels long since finished, the villagers tell me. Like everything else in Sumte, it’s become part of the historical record.

Bagunk, the innkeeper in Amt Neuhaus, tells me she’s sorry to see them go. She enjoyed the liveliness that descended on the town for a few months. “There were even lines at the supermarket,” she says. Her business also benefited from the bluster of news crews, the reporters from Al Jazeera and Der Spiegel sneaking about the woodpiles. (“All these reporters, tigering around,” Schieferdecker had told me.) Now it’s quiet again.

In her office, Richter pats herself on the back. It was a great success, she says. There were no Nazis, no mobs, no violence. That’s all she could have hoped for. A local credit union has offered to buy the Apontas building. Maybe they’ll sell it. Maybe they’ll turn it into a refugee job center, she hopes, although I point out that any interested refugees would have to travel from Lüneburg or Hannover, since they wouldn’t be living in the camp. That’s true, she admits. The place will no longer be a shelter. “I won’t be delivering any more of those,” she says, and points to the corner of her office, where for the first time I notice a row of green backpacks lining the far wall. Each is filled with baby formula, diaper coupons, towlettes, and a onesie. She’s visited every newborn under her jurisdiction for the past five years, she says, including the three documented camp births since last October: three babies born into exile on the Elbe.

In Sumte I waylay Thomas, the Platt-speaking housepainter, who is taking a Sunday walk with his wife and their own swaddled newborn. “They’ve harvested the fields and the hard work is finished,” he says. “The camp is closed. The lütten is here. All is good heading toward Christmas.” On that note, they walk away, not even saying goodbye, eager to turn their attentions to Sumte’s 103rd citizen: the lütten, the little one.

I drop in on Dirk Hammer, who is busy in his workshop. He feels ambivalent about the camp’s closing. A year ago he’d railed against Hannover and Berlin in Facebook posts that mocked politicians with no concrete solutions to the crisis. But he’d come to be one of the most recognizable faces in town when the media circus descended. He was never afraid to liaise with the press. He was the bicycle man, a welcoming figure. Now he stops his work to tell me that what the area really needs—what no journalist will dare report on—is jobs: not the sixty or seventy that the refugee camp provided, but hundreds. It’s sad that the camp closure will mean the loss of work, he says, but where was the public outcry when Apontas moved away? “It has nothing to do with refugees,” he says. “We need jobs.”

Which isn’t to say they wouldn’t do it again. “Of course we would,” he says, “but we wouldn’t necessarily be happy about it.” He thinks for a minute. “Although we did get the streetlamps.”

From Hammer’s workshop I walk around a barn filled with milking cows into a soft-focus September afternoon. The sidewalks are veined with snail slime. Sheep are shorn and raw. The Arabian horses stand around chewing, their faces shimmering with black flies, and the Arabic/English signs warning people away are gone. Instead, the new lampposts are adorned with campaign posters for next week’s state elections. The bridge is once more an issue of top importance. The roadside pears are hard and cold, with almost no sweetness.

In the camp conference room, Meier sets out plates of cookies. He’s about to host a meeting with Richter and a dozen other administrators to discuss ASB’s withdrawal and the future of the site. Nobody can say yet what will happen. As he works, Meier thinks about good memories of a nature camp he’d attended as a boy, out in the countryside. Maybe someone could found a nature camp here, with fishing and horseback riding.

“I guess it’s not very likely,” he says.

On previous visits, I’d been limited to public rooms, but now Meier says I can wander as I please and take as many pictures as I like. I stroll down the long hallway to which twenty-one prefab warehouses are attached on either side, like the stumpy legs of a centipede. The once-bustling cell-phone store, the cafeteria, the medical station, the ladies’ clothing boutique, and the social workers’ offices all stand empty. A few remaining workers are breaking down plywood structures. Metal bed frames line one side of the hall. In the former kindergarten nothing has been touched. Action figures and fantasy playsets are frozen in mid-play, like something you’d stumble upon in a Pompeii living room. Dishware and samovars have been tidily arranged along the windowsills and atop an archipelago of folding tables in the middle of the former dining hall. In one room, a heap of thousands of pillows touches the ceiling. It’s quiet and dark among these piles, insulated by pallets of hundreds of foam mattresses.

The very last room is a storage area. It’s filled with every domestic item imaginable, from boxes of donated clothes to jugs of ammonia to aquariums and clock radios and all of Hammer’s bicycles, lined up against a dozen baby strollers.

A young woman from Amt Neuhaus escorts me back to the entrance. She started working at the camp in January, during her last months of high school. Now she wants to study social work at university. The camp was wonderful, she tells me. People really got along. “Some of the refugees who left months ago have even written to ask if they might come back,” she says. They’re unaware that the camp has closed for good. They write that the accommodations here were so nice, the people so friendly.

So what went wrong? I find Meier’s explanations—the lack of internet, the shock of winter—unconvincing. I think back to Merkel’s early optimism, which turned to nationwide skepticism as a plan for integration failed to appear, as we instead accustomed ourselves to a haphazard collection of camps scattered across the country in villages of the unprepared. Was there ever a specific vision of success?

“Character is fate,” the German Romantic poet we know as Novalis once wrote, loosely translating Heraclitus. It is a very German idea. This is the country where Romanticism was born and never really died, although it has undergone numerous transformations. It could be accused of inventing race thinking, writes Hannah Arendt, just as political romanticism could be accused of inventing “every other possible irresponsible opinion.” In the twentieth century, Novalis’s sentiment reached extremes of national and racial character during the apocalyptic endeavor called National Socialism. And as the refugees started pouring into the EU, people began talking once more about Germany’s national character. It was often suggested that only here in Germany—a country more deliberately deprogrammed than any other from the myths of ethnic tribalism—could such an experiment in asylum take place. Never mind that this was simply the inverted, world-positive remix of the Nazi fantasy: that Germany was fated to, in the former case, produce a kingdom of Aryan supermen, and, in the latter, adopt the world’s refugees, because of its character (meaning in the post-reunification sense its historical awareness, its liberalism, and above all its wealth). Forget the details, Merkel seemed to be saying, we will manage it somehow because this is who we are. “If we now have to start apologizing for showing a friendly face in response to emergency situations,” she said, “then that’s not my country.”

I wonder whether this belief in Germany’s righteousness—its constitution-bound duty to protect human dignity—didn’t do more to harm Merkel’s efforts than all the country’s xenophobes and fearmongers combined. In Sumte I saw many nervous people willing to give refugees a chance, but with a few exceptions—Meier, Schlemmer, Hammer—they kept their distance. They retreated into private life. Too many people in Germany, and throughout Europe and beyond, seem to have believed they could leave things to the experts. They assumed, in other words, that character is fate: that some abstract “Germany” would take care of the crisis.

Arendt warned us against this idealism, too. “No paradox of contemporary politics is filled with a more poignant irony,” she wrote in 1949, than the discrepancy between the efforts of idealists who talk about “inalienable” human rights, and “the situation of the rightless themselves.” Such rights are never guaranteed by documents or goodwill. They are preserved only by perpetual effort. “We are not born equal,” she writes. “We become equal as members of a group on the strength of our decision to guarantee ourselves mutually equal rights.”

If the myths of nations will not protect the stateless, nor does empathy alone suffice. I saw the natural limits of empathy in Sumte, where for safety’s sake—out of a not inconsiderate desire to protect the vulnerable—refugees were isolated to an intolerable degree. It would take a kind of radical courage to replace this empathy born of pity, which does nothing to erase the otherness of the protected, and can never blossom into fraternity, much less friendship. It would take a kind of faith.

Character is not fate. It requires extraordinary effort to renew one’s character, all the more so in the realm of politics. People in places like Sumte must first believe they have the power to remake the world, rather than merely survive it. It’s not clear to me how such a change might come about.

At the end of my last visit to Sumte, I drive out to the preserved East German watchtowers along the Elbe, where in the gutter that marks the former death zone families are taking Monday evening strolls. Strapping sons are playing with golden-haired dogs. Fathers are holding daughters’ hands. Each family stops whatever they’re doing to levy a collective gaze on this stranger waving to them from a rental Škoda with Slovakian plates, and they keep on staring until I’m out of sight, and in their faces I discern nothing friendly—only mistrust. What did I expect? Here are people whose oldest wish is a bridge to somewhere, who have failed to muster an atom of political strength over a thousand years of residence. When change comes, it’s because a stranger arrives and forces it on them, and the change is rarely for the good. They have never participated in their country’s remaking. They are never invited to the table where their futures are written, the table where, since reunification, the land in the regions near Sumte has been suggested as a final repository for the country’s nuclear waste. The high salt content of the earth makes it an attractive storage site.

Education Resource

Meet the Journalist: Max Duncan

Filmmaker and video journalist Max Duncan profiles a family from the Yi ethnic minority in a remote...

Education Resource

Meet the Journalist: Ben Mauk

Ben Mauk discusses his year-long Pulitzer Center project on the EU asylum crisis, which culminated...