Afghanistan was no longer safe for 14-year-old Milad and his family.

They needed to get out fast to escape the threat of the Taliban.

“We sold our home, our animals, my mom’s jewelry … everything,” the teenager told photographer Diana Markosian.

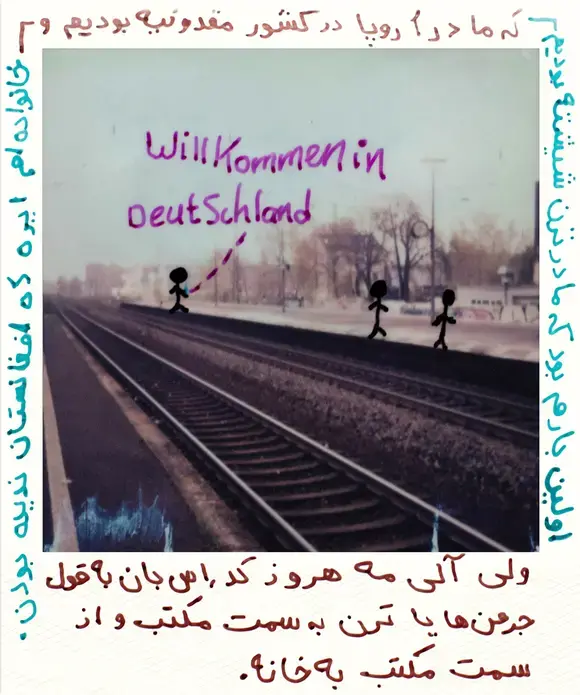

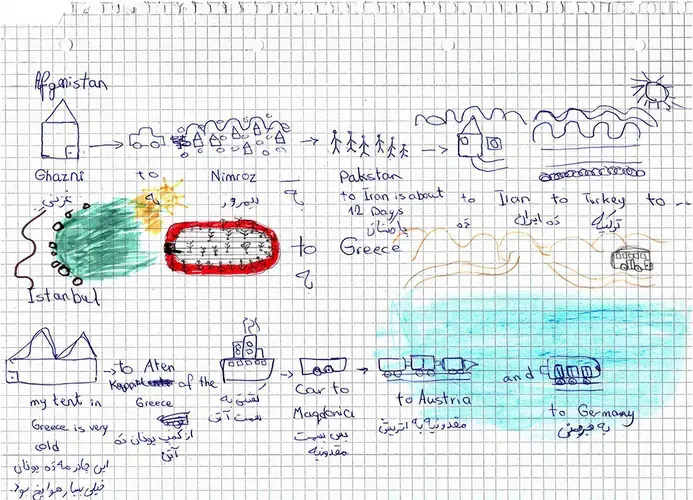

In all, the family spent about $26,000. Milad was smuggled out of the country along with his parents and his two younger sisters. They traveled for three months — crossing various borders by car, train, boat and foot — before ending up in Germany, where they are now seeking asylum.

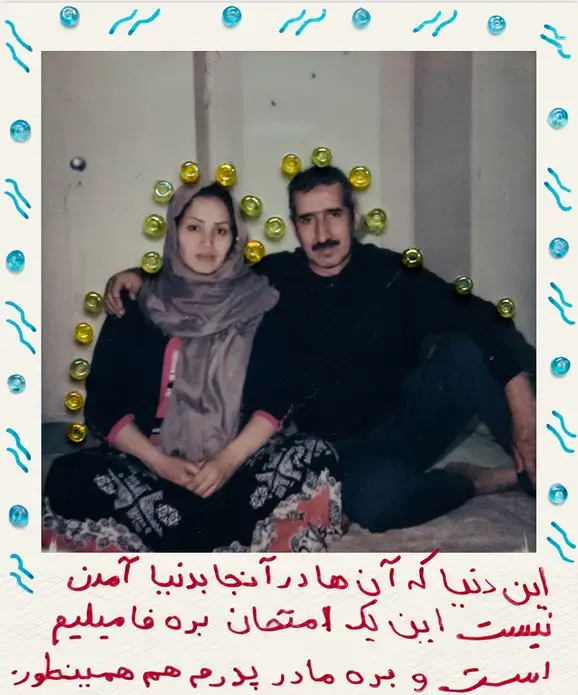

Markosian met Milad in September, when the family was living in a migrant center in the German city of Dusseldorf. She had come to the country looking to do a story on a family starting a new life there, and she was invited to Milad’s shelter by Krass, a German nonprofit running an art therapy program for children.

“Milad came up to me, and he was very open and very earnest and quiet,” Markosian recalled. “He just had a different sort of energy to him.”

He also spoke English, having learned it in school in Afghanistan, and that made it easier for the two to relate.

“He started telling me about his family and I asked if I could meet his mom, his father and sisters,” Markosian said. “We had dinner that very first night. I remember going home thinking, this is the family I want to be with for the next few months.”

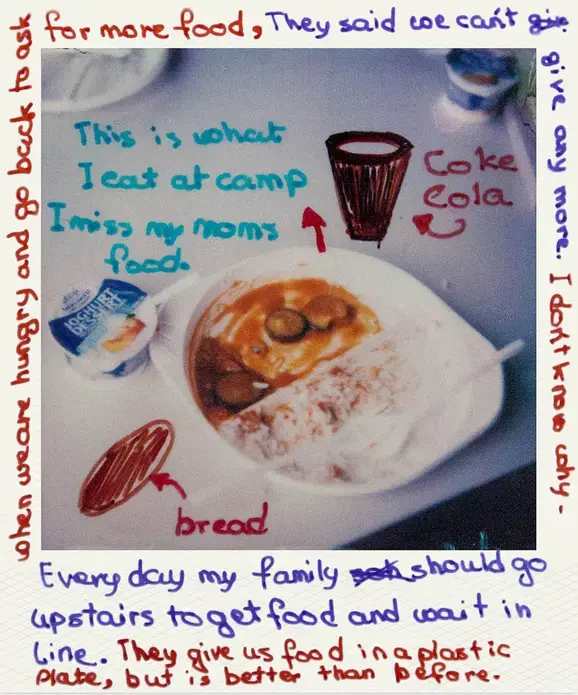

The family had been in Germany for about half a year. They were living in a large building with other migrant families. Each family had their own room, but bathrooms were shared and everyone ate in a cafeteria upstairs.

The food may have been the hardest part for Milad and his family.

“They could never cook for themselves because they never had a kitchen. None of the refugees did,” Markosian said. “For breakfast, they would have bread and jam. For lunch, they would have bread, jam and maybe spaghetti. If you think about it, it’s the most random sort of food for a family coming from elsewhere. They're not used to any of these flavors or tastes or smells, and all of a sudden they're consuming it on a daily basis.”

Milad stopped eating, and he lost about 15 pounds.

“I eat two sandwiches every day,” he told the photographer. “It’s not very good. I miss my mother’s food.”

But Milad said he and his family were still very happy in Germany. They felt safe, most of all, and they were able to experience things they had never had before.

Milad had never seen a train until he came to Europe. Or a supermarket. Or an elevator. He was amazed by Dusseldorf’s “too clean” streets, and the big homes where “when it rains, it’s not wet inside.”

He also enjoys school, although it takes him an hour to get there by bus and train.

“I think he's adjusting,” Markosian said. “He has a crush on a girl. He speaks German. He has a few friends — not many German friends, but he has a few friends. And I think he really likes learning.”

Markosian spent about a month and a half with the family before even picking up a camera. And then when she did start her project, she wanted to involve them and let them have some ownership of the story. She gave them a Polaroid camera.

Milad’s Polaroids, along with his drawings and writings, combine with Markosian’s work to give viewers a sense of what it’s like adjusting to a new country.

“They don't have a photo album from Afghanistan, and when I learned about that I really wanted to give something back to them that they could remember and have for themselves,” Markosian said.

Markosian can relate to the family in many ways, as she was also an immigrant. She came to the United States from Russia 20 years ago.

“When I was a kid, my mom woke me up one morning and said we were going on a trip — and the next day we arrived in America,” she said.

Markosian used to watch the American soap opera “Santa Barbara,” and that was the California city they migrated to.

“That first year in America made a real impression on me when I was a child,” said the photographer, who now lives in Los Angeles. “It’s been interesting for me to document someone who mirrored that experience I had, all these years later.”

Milad’s family had their final asylum interview in December, and they are still waiting to hear whether they will be allowed to stay. In the meantime, they’ve added a new member — a baby girl named Zeynab — and moved into a new facility where they finally have their own kitchen and their own bathroom.

Markosian said the family is eager to assimilate. They are learning German. The father, Mohammed, wants to be a chef. The mother, Aziza, hopes to be a nurse.

“Sometimes when the weather is rainy, I feel not so good,” Milad told Markosian. “I think about my friends and my uncles and sometimes I (cry). I feel just sad because I remember Afghanistan.”

But when asked if he wants to go back, Milad is unequivocal.

“No. We have nothing there anymore.”

Education Resource

Meet the Journalist: Alice Su

Amid an ongoing refugee crisis caused by worsening conflicts in the Middle East, Central Asia, and...