Devon Parfait, 25, was in second grade when Hurricane Rita destroyed his grandfather’s home in Dulac, Louisiana. The 2005 category 5 storm transformed the tranquil community he knew into chaos. It took three weeks for the six feet of water in the home to return to the bayou. Mold replaced it—covering the zoo books he’d spend hours thumbing through.

“We pretty much had to abandon everything,” Devon said.

Rita decimated the low-lying fishing village. It left nearly 9,900 homes almost unrecognizable in Terrebonne Parish. But perhaps the most devastating blow came months later. Many members of the Grand Caillou/Dulac Band of Biloxi-Chitimacha-Choctaw tribe credit Hurricane Rita for the first wave of displacement that continues to ripple through the community today.

Thousands of applicants in Terrebonne Parish were denied aid from the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA), including Devon’s grandfather Wilton “Pierre” Parfait, 68.

Pierre, a tribal elder, and his wife Gwen couldn’t keep paying mortgage on an unlivable home. So they cut their losses, demolished their home of 10 years and sold the land to Road Home, who seemed to be buying everyone’s land those days.

Pierre never dreamed his homeland would be in his rearview mirror.

He and his family survived plenty of hurricanes when he was growing up in Dulac. Before they had a hose, they’d splash buckets of water over the silt that the storm blew into their home. He witnessed his mom and dad spend what they had to cling to the land of their ancestors.

But, in the end, Hurricane Rita uprooted him.

“It was like pouring money into a hole and letting the water take it,” Pierre said.

In the span of primary school to high school, Devon changed schools more than four times.

“I think that was the toughest thing for me growing up,” Devon said. “Whenever I was living on the bayou, I felt like I was living on the bayou with all my family. We got to go shrimp, and I got to be a part of the culture. But we had to move and I lost that.”

He felt homesick. Isolated. Disconnected. Devon yearned to be immersed in his culture—to navigate the bayou on his grandfather’s shrimping boat. He wanted to grow up native.

“I wasn't involved in the traditions as much as I could be,” Devon said. “I didn't speak the language, which is not just a me thing, it's common throughout my generation. A lot of the things that you would consider somebody to be Native American in Louisiana, I was kind of distant from. That affected the way that I thought about my identity.”

In a way, his grandfather “Papa,” as Devon calls him, felt similarly just on the other side of the spectrum.

Pierre lived with one foot on the shores of Dulac and another on a shrimp boat. Since age 5, he’d join his dad on the boat down Bayou Grand Caillou almost to the Gulf of Mexico.

“That was when there was land on both sides,” Pierre said. “Now there is hardly nothing there.”

The water chipped away at the land, and over time, Pierre saw his family home change from being the highest up in the neighborhood to being the lowest.

He’d seen his mom make fry bread, a cultural food, thousands of times without a single measuring cup in sight.

But discrimination toward natives forced him to have to hide his identity. While on the way to his first job at 12 years old, Pierre’s father told him to never mention they were native.

Storefronts often plastered “whites only” signs. Segregation in public schools limited the natives’ access to education, too. As a result, Pierre’s siblings never learned to read or write. Many tribal elders from that generation still don’t know how.

But leaving Dulac behind changed things. The land the tribe called home for centuries was disappearing under the water. And its people were scattering across the state and beyond. Pierre felt an insurgence to preserve native traditions.

“I had to learn a lot to teach the kids,” Pierre said. “But so much of the culture was lost.”

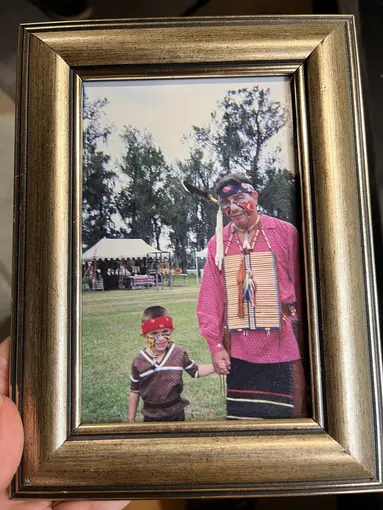

He read books, went to pow wows, and talked to his relatives and other nearby tribes to learn about the Grand Caillou/ Dulac tribe. He shared that knowledge, too. Pierre used money from his own pockets to host camping trips for his grandkids and other Native children in the area.

“I don't really know anything about being Native other than what my grandpa has taught me, which was a good bit,” Devon said.

When Devon was 12, he took an interest in Chief Shirell Parfait-Dardar's work. She’s the chief of the tribe and one of the few homes Devon’s mom, Dana, trusted him to stay with.

It was late at night, and Parfait-Dardar was working on federal acknowledgement for the tribe. The tribe is state-recognized but has been working to be federally recognized since the 1990s so that they can communicate their needs directly to federal entities, like FEMA.

Devon was curious about the process. Parfait-Dardar remembers him asking her how he could help the tribe.

“And I just felt it,” she said.

At that moment, she realized he would be the next chief. She named him Future Chief.

That may seem like a lot of pressure to put on a 12 year old. But Devon was ready to be the leader his tribe needed.

“This responsibility is ancestral,” Devon said. “For as long as humans have been around, the responsibilities of the community are passed down to each generation.”

Parfait-Dardar wanted school to be a priority for Devon. But it didn’t come easy to him. He struggled with depression throughout high school after a close relative passed. His GPA was low, but he graduated and worked his way into Williams College where he studied geoscience and maritime studies.

“I needed him there because the land is what he's going to be fighting for,” Parfait-Dardar said. “I needed him to understand everything about it. I did not have that education. You know, education is something that was always preached by our people because they weren't afforded an education. And that's the one thing that they can't take from you.”

Devon focused his studies on tribal coastal land loss in Louisiana. His research found that the state loses 0.3% of its land each year, but the Grand Caillou/Dulac area loses 0.7%.

“I've been able to quantify for the first time how coastal land loss was affecting the tribal communities,” Devon said. “We knew anecdotally that it was disproportionately affecting these communities. But nobody had ever been able to do any work on that.”

Devon transitioned into his role as chief of the tribe in August 2022. He plans to use his knowledge about coastal land loss to benefit his tribe.

He is currently working as a coastal resilience analyst in Louisiana. Devon can’t stop coastal erosion, but he intends on getting the tribes a seat at the table discussing it. There are ways we can slow it down, Devon said.

“Things have to change or your grandkids will never see it,” Pierre said.