With few options, some Haitians left no choice but to live and work without papers.

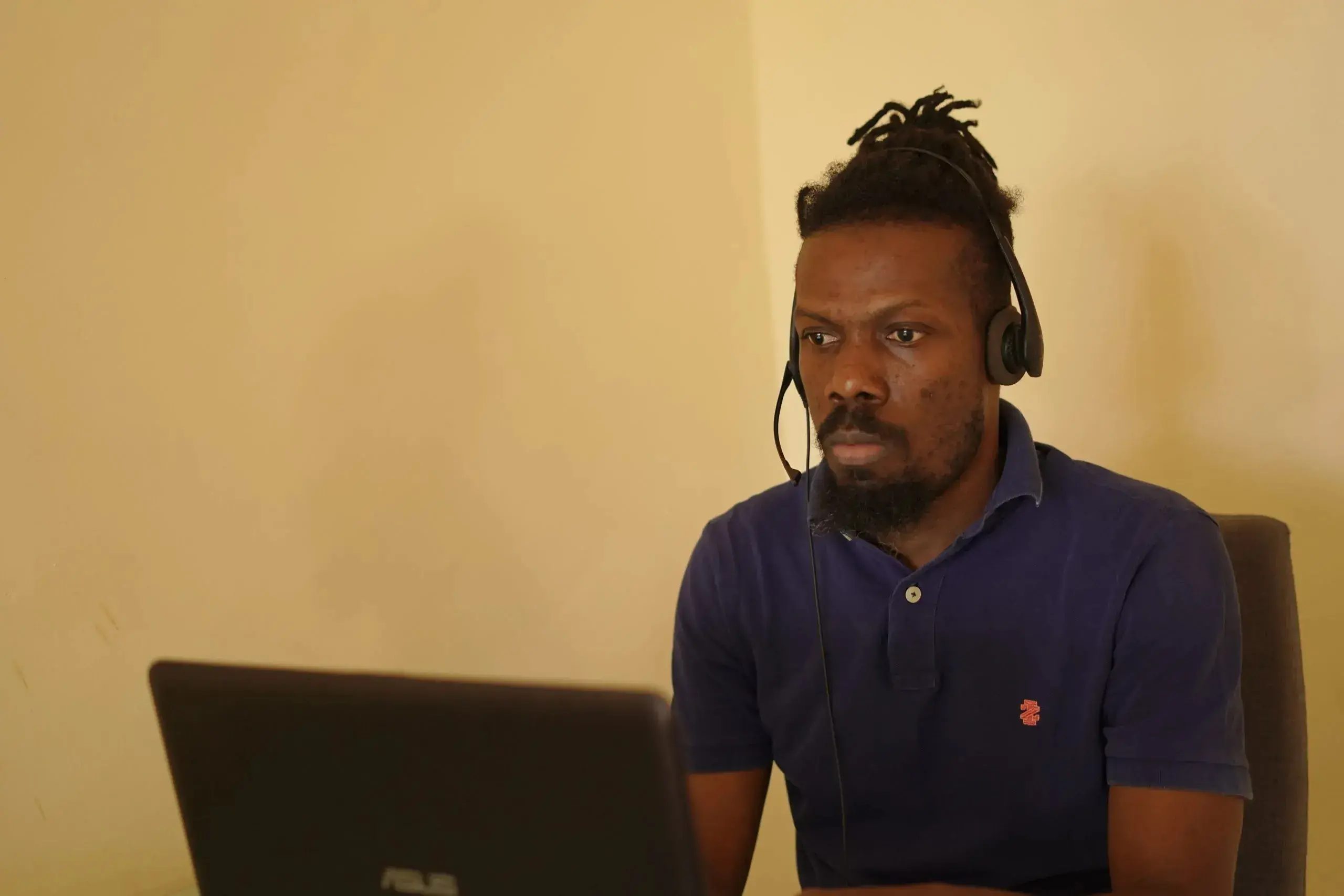

SANTO DOMINGO — Since moving from Haiti to Santo Domingo in January 2022, Yves Junior Mabial, a call center agent, has not been out to a nightclub, the beach or even a pool.

Mabial, 40, has left his residential building only about four times during the 12 months since he arrived. When Mabial is not working at home, he spends his day on Netflix, Twitter and texts with his friends.

His prison? Fear of being sent back to Haiti.

As a nonprofit journalism organization, we depend on your support to fund more than 170 reporting projects every year on critical global and local issues. Donate any amount today to become a Pulitzer Center Champion and receive exclusive benefits!

“I’m always afraid that an immigration agent will get me and put me back in Haiti. That’s my main fear,” Mabial said, as he sat in his living room one afternoon in January.

“If Haiti can get the minimum security, I would go back to my country because I’m like in a prison — because I’m illegal,” Mabial added.

Many Haitians in the Dominican Republic — even those with some means and jobs, like Mabial — live an anxious existence in hiding, always looking over their shoulders. They live with this constant kè sote, heart skipping, because immigration officers might turn up at any moment to enforce Dominican migration laws that have become ever stricter for Haitians who want to become or stay legal residents. These immigration laws, scholars have said, aim to keep Haitians out because of a long-standing pervasive fear that Haitians will take over the entire island once again.

Human rights advocates add that the laws lead to discriminatory practices that criminalize Haitians for simply being present on the Dominican side of the island. The fear has been behind a slew of transgressions and stricter immigration control policies as more Haitians move to the neighboring country, including deportation. Because of them, Haitians are forced to leave Dominican soil through mass repatriation, such as the 140,000 Haitians returned in 2022, according to the Support Group for Returnees and Refugees (GARR). Because of this period of mass repatriation, many Haitians living illegally in the Dominican Republic are living in hiding or on the run.

“I ride with my heart skipping beats … I always see the [immigration] guys when I’m on the road.”

Schnider Brutus, Taxi-Moto Driver

Oftentimes, those born in the Dominican Republic become victims of repatriation because the Dominican Republic does not grant birthright citizenship to anyone whose parents were not Dominican – going back to 1929.

Schnider Brutus, a taxi-moto driver in Santo Domingo, falls in that group. He was born in the Dominican Republic and has only been to Haiti once. Brutus rolls his R’s when he speaks Creole and does not know Haiti’s Prime Minister’s name. Nevertheless, he lives under the threat of being sent to Haiti.

“I ride with my heart skipping beats because the situation is very difficult,” Brutus said. “There’s a lot of deportation, and I’m illegal now. And I always see the guys when I’m on the road.”

He was almost deported in the winter of 2022.

Brutus was riding on his motorcycle after coming from work with a friend in the passenger seat when he spotted the car of immigration officers in Santo Domingo. The immigration agents asked them to stop. Since he does not have a Dominican identification card granted to legal residents and citizens, Brutus pulled one officer aside and offered him 2,000 pesos, or $US 35. The agent took the money and let them go.

Brutus was still driving a taxi-moto in January 2023. He must, he said, to earn his living since it’s difficult to get another job without papers.

As for Felix Etienne, he paid a Dominican coyote 4,000 pesos, or $72USD, to cross the border illegally by car in 2023. Since then, Etienne, who now has a wife and infant son in the Dominican Republic, has been repatriated twice. But both times, he snuck back to the Dominican Republic.

“I spent a lot of days in Haiti but couldn’t take it anymore,” Etienne said. “I kept thinking about my wife and my child.”

Etienne, a construction worker, used to play Division 2 soccer when he was in Haiti, but said he mostly works in the Dominican Republic and goes home afterward. Similarly to Mabial, Etienne does not like living in hiding, so he is hoping Haiti can get better so he can return home.

“I left Haiti and came to Santo Domingo because I can make one gourde here — for no other reasons,” Etienne said. “If I could’ve made it in my country, too, I wouldn’t have had the vision to leave it.”

But the living conditions in Haiti getting better is far-fetched, so some also have their eyes set on other countries, such as Mexico and the United States, where they believe it is easier to become legal than in the Dominican Republic.

“The Dominicans don’t give us Haitians opportunities. They don’t open the door for us to integrate into their system,” Mabial said. “I will save some money and get to a place where I can get a status. At this moment, Mexico is the new El Dorado for immigrants. And it’s right next to the United States.”