Industrial plantation forest companies (HTI) in Riau, Jambi, and South Sumatra are using the social forestry program to expand their concession areas and increase their timber supply.

On the side of the road leading to Wirakarya Sakti (WKS), Sopyan bin Aroni observed a row of acacia trees over eight meters tall. That afternoon, on June 13, shrubs crowded the ground where these trees stood. The straight acacia trees with diameters ranging from 15 to 20 centimeters grew on a social forestry land managed by the Pajar Hutan Kehidupan Cooperative in Sengkatu Baru village, Batanghari, Jambi.

To the north of the social forestry land is district VIII of the concession area managed by Wirakarya. The subsidiary of Sinarmas Forestry—the largest industrial plantation company (HTI) in Indonesia—had just planted eucalyptus to be processed into pulp. This is why, in June, the trees were still small and short, with pink shoots.

According to Sopyan, 53 years old, Pajar Hutan Cooperative’s acacia trees on their social forestry land could have been harvested as they were already five years old, a ripe age for acacia. “(We) can’t harvest (the trees) yet because the RKT (annual work plan) has not been issued,” said the chairperson of the Pajar Hutan Kehidupan Cooperative’s supervisory body. In order to harvest, the RKT must first be approved by the Production Forest Management Unit (KPHP), which oversees the government forest area.

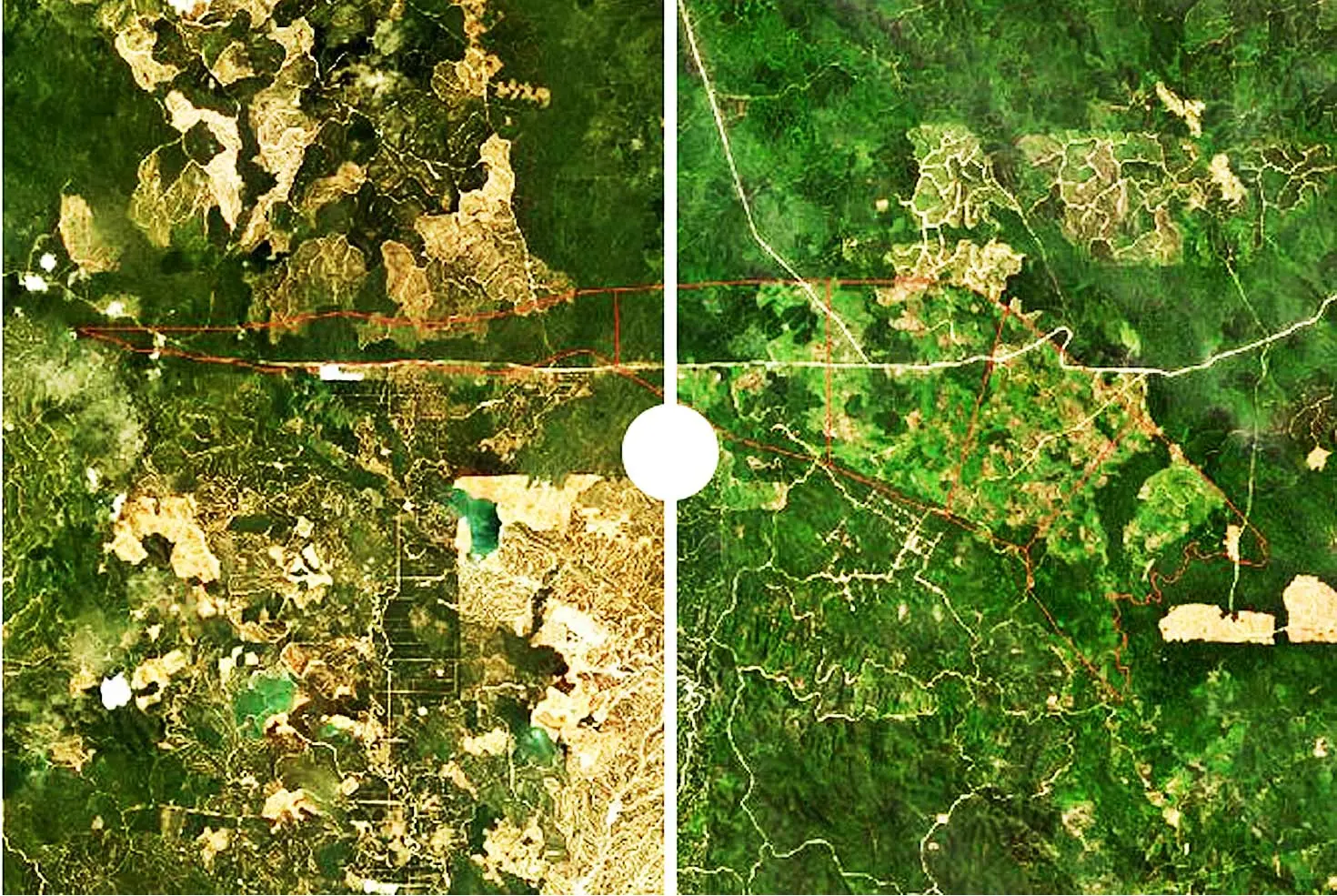

The Pajar Hutan Cooperative, with 50 farmer members, received a social forestry management permit on October 4, 2017, for an area of 517.26 hectares. The permit is for 112 hectares of plantation and 111 hectares of logging. Based on satellite imagery, 443.72 hectares of the land’s cover take the form of plantation forest, oil palm, and shrubs, while natural forest take up only 27.11 hectares.

According to Sopyan, there is around 80 hectares of acacia trees in the three blocks ready to be harvested. As a partner of the cooperative since 2018, Wirakarya will be purchasing the timber. The cooperative will receive a share of Rp50,000 per ton of timber. If each hectare contains 1,300 acacia trees with a volume of 100 tons per hectare, the cooperative would receive Rp400 million. Because acacia is harvested once every five years, each farmer receives Rp132,000 per month.

Whistleblowers and others in possession of sensitive information of public concern can now securely and confidentially share tips, documents, and data with the Pulitzer Center’s Rainforest Investigations Network (RIN), its editors, and journalists.

The KPHP Batanghari only approved Pajar Hutan Cooperative’s RKT three months later. “We want to make sure that they’re responsible,” said Feri Irawan, head of KPHP Batanghari, on Tuesday, September 13. “The RKT is not only about harvesting but also about replanting.”

Four other cooperatives are in a partnership with Wirakarya Sakti, namely Hijau Tumbuh Lestari, Rimbo Karimah Permai, Alam Tumbuh Hijau, and Alam Sumber Sejahtera. The administrators of these five cooperatives then formed a joint cooperative under the name Rimbo Kehidupan Lestari. The joint cooperative manages a community plantation forest with an area of 3,142.49 hectares.

The problem is the acacia trees ready for harvest were not planted by members of the cooperative, but by Wirakarya employees. According to Chief of the Jambi Forestry Office, Akhmad Bestari, local residents have long thought of the area as the company’s concession area, so that they don’t manage the land and simply let the company’s employees plant it with acacia.

Wirakarya’s forest area demarcation and work area show that the acacia trees lie outside the company’s concession area. “The environment and forestry ministry turned (the area) into a social forestry area,” said Bestari. Wirakarya agreed that the plants should be owned by the cooperative. According to Bestari, that is why the cooperative forged a timber trade agreement with Wirakarya and the government has not sanctioned the company.

Wirakarya Sakti was founded in 1996 as a HTI company that supplied timber for Lontar Papyrus Pulp and Paper Industry. Wirakarya has a concession area of 290,378 hectares, according to the fourth revision in 2018. Wirakarya’s forest concession is distributed through eight districts in 134 villages and five regencies. “Our role is as an off-taker, which purchases timber from social forestry communities,” said Daulat Sitorus, Wirakarya’s Head of Social Affairs and Security.

Riau is a different story. In Siak, there is the Kelompok Tani Mandiri (KTM) Sejahtera, a farmers group that received a community forest permit for 980 hectares of land last year. But head of the Dayun village, Nasya Nugrik, says that administrators of the KTM Sejahtera, without permission, have used the names of the members of the Tunas Harapan farmers group that was established by the previous village head. Nasya has led farmers in managing 700 hectares of social forestry land since 2014.

But the environment and forestry ministry (KLHK) still issued a social forestry permit for KTM Sejahtera. “After the permit was issued, it was Nusa Prima Manungga (NPM) who ended up managing the land,” said Nasya. Nusa Prima was founded by tycoon Sukanto Tanoto in 1998. According to NPM’s articles of incorporation, Sukanto, its Chief Executive Officer (CEO), doled out an initial capital of Rp1.25 billion.

According to the sustainability section of April Group’s website, Nusa Prima is the supplier of pulp and paper for Riau Andalan Pulp & Paper (RAPP). April Group is Sukanto’s business group, while RAPP is also Sukanto’s company. Nasya suspects that KTM Sejahtera was created by Nusa Prima and was prepared to plant trees for timber and supply the company.

As a proof, Nasya referred to the role of Brando Sirait, a Nusa Prima employee, who has been applying for social forestry permits on behalf of KTM Sejahtera. Brando’s name is recorded as a person assisting farmers in a report on technical verification with the forestry ministry’s letterhead, signed by the social forestry and environmental partnership office.

There is also Kesatria Ginting, who chairs the KTM Sejahtera. In Dayun, Kesatria is known as an oil palm businessman. According to Nasya’s map, KTM Sejahtera’s social forestry area directly borders RAPP’s concession area. On the way to the social forestry area, one must go through the oil palm plantation managed Kesatria Ginting’s family.

In Penarikan village, Langgam subdistrict, Brando Sirait’s name is also familiar to administrators of the Penarikan Jaya Village Unit Cooperative (KUD), which received a social forestry permit for 1,379 hectares on May 31, 2018. They refer to Brando as the cooperative’s assistance provider from Nusa Prima.

KUD Penarikan Jaya chairperson, Mus Mulyadi, admitted that his cooperative has had a partnership with Nusa Prima as a timber supplier since 2004. “NPM took care of processing (the area) into a social forestry area, so that the timber can go to RAPP,” he said.

Prior, the area worked on by social forestry farmers in Riau was made up of community forests and privately owned forests. But in 2018, the forestry ministry reorganized the borders of these areas. As a result, those areas were included in the production forest.

But without the knowledge of cooperative administrators, Nusa Prima proposed the area to be changed into a community forest (HKm) under the name Penarikan Jaya KUD. “Suddenly it was changed into a community forest, and we didn’t know what community forest was, what social forest was,” said Mus.

According to the agreement, Nusa Prima purchases acacia timber from the cooperative at Rp3.5 million per hectare per five years per farmer.

Brando Sirait refused to be interviewed, saying that he did not yet have the approval of Nusa Prima to provide a statement. Meanwhile, Kesatria Ginting was not at home when TEMPO visited. Neither has he responded to TEMPO’s questions. “NPM provides less than 1 percent of (our) fiber supply,” said Sihol Aritonang, RAPP CEO, in a written statement.

In Ogan Komering Ilir, South Sumatra, the community’s efforts to manage their social forestry area has been hampered by permit issues. In 2019, administrators of the Mulya Jaya Lestari Abadi Cooperative from Jadi Mulya village applied for a social forestry permit for 1,462 hectares. The forestry ministry rejected the request.

Forestry Ministry’s Director-General of Social Forestry and Environmental Partnership, Bambang Supriyanto, said the area is part of the Sugihan River-Lumpur River Peat Hydrological Unit. According to regulations, social forest on peatland can only produce non-timber products. “Community plantation forests can’t be located on peatland,” he said.

The area requested for a social forestry permit falls under the concession area of OKI Pulp & Papers Mills—Sinarmas’s paper manufacturer and part of the Asia Pulp & Paper, which is currently on the social forestry indicative area map, revision VII, with the note that it is an area reserved for a forest estate exchange mechanism. In 2012, OKI wanted to build a factory in the area, but the location was moved to Sungai Baung, around 30 kilometers from the concession area.

Two years after the forestry ministry rejected the application for a social forestry permit, villagers who fish in a river near the forest area every day, saw heavy machinery going back and forth. “Why can’t the local community manage the land while the company is permitted to?” asked Haryanto, chairperson of the Mulya Jaya Lestari Abadi Cooperative in Jadi Mulya village, in June.

Bumi Andalas Permai’s Head of Social Affairs and Security, Tunggul Wachidin, admitted that his company planted acacia trees in the area last year. “When (we) began planting, there was no timber potential, only shrubs and small cajeput trees,” he said.

According to Head of the Lumpur Riding River Area IV Forest Management Unit, Riding Sigit Purwanto, the acacia planted by Bumi Andalas was meant as reforestation. “(It is the) type of plant that usually grow there, by taking from surrounding areas,” Sigit said on Tuesday, September 20.

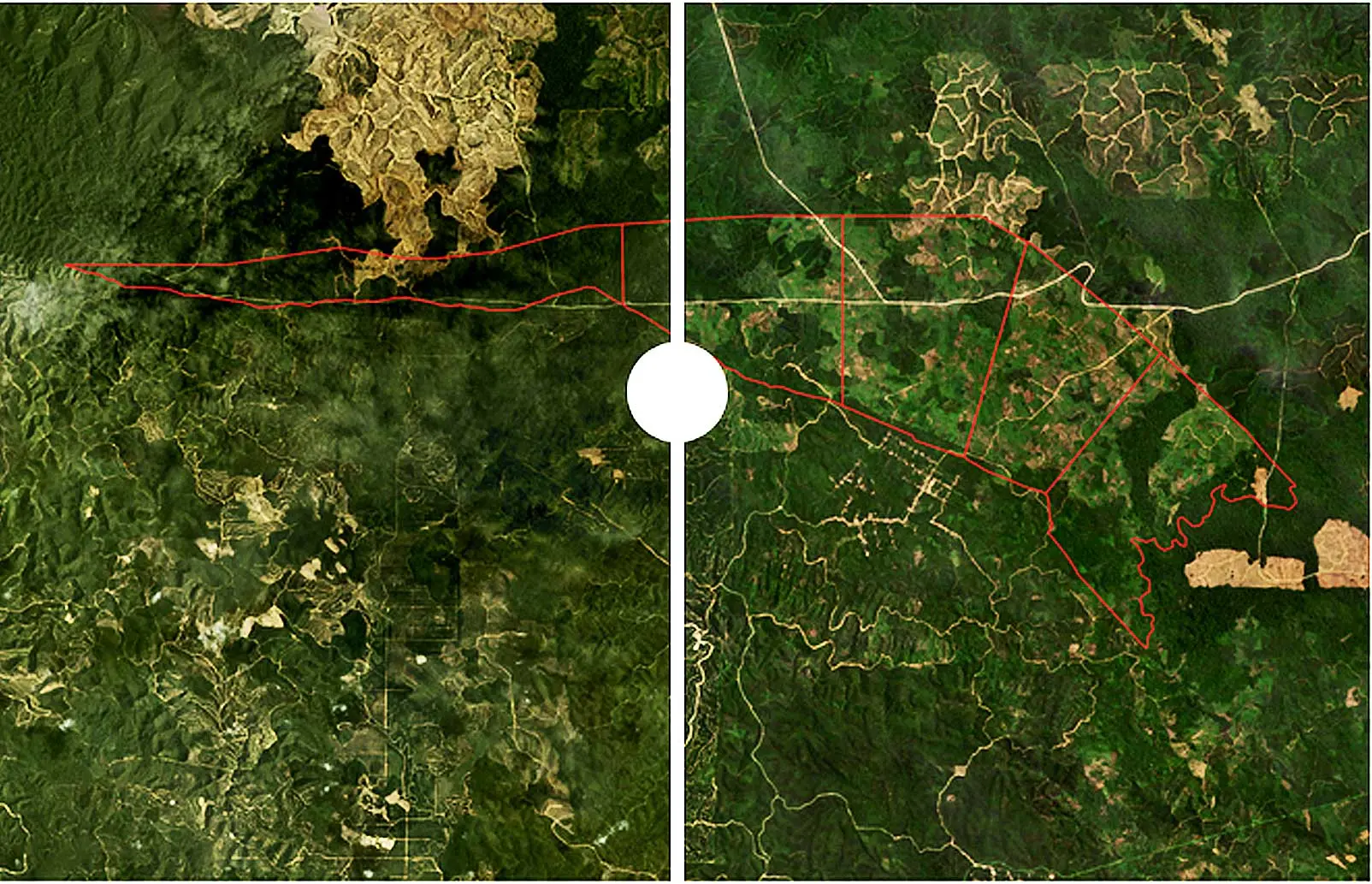

In mid-June, TEMPO visited the forest by following the river on a wooden boat. There were canals surrounding peat that was beginning to dry. Acacia had indeed grown on the 802.7-hectare production forest, while 602.7 hectares were still being cleared.

At a canal near the delta of the Simpang Heran River, there were wooden huts and five units of heavy machinery. “Stacking for Bumi Andalas,” said one employee, who said he came from Jambi and had been in the location for five months to clear the land. From above, these peat canals lined up neatly. The canals were 1 x 0.5 kilometers on average.

Not far from the concession area, there was an other-use area (APL) of 558.2 hectares already planted with acacia trees, which were around three months old. APL is land outside of government forests, managed by regional governments. According to Tunggul Wachidin, OKI manages 1,009 hectares of APL.

Tunggul says the forest estate exchange area managed by OKI has already been turned into a production forest with an area of 1,406.87 hectares. According to him, in line with Minister of Environment and Forestry Decision No. SK. 383/2018, issued on September 6, 2018, OKI received the right to manage the area with the obligation to perform reforestation.

To this end, said Tunggul, the company forged partnerships with three agroforestry farmer groups, i.e., Sido Makmur, Maju Bersama, and Sido Muncul, on May 15, 2018. Eighty families are involved in managing 181 hectares in the Simpang Heran district. But the community has not worked on the land because the area is often flooded.

But, Tunggu explained, the company’s partnership with farmers is not only meant for this area. Out of the concession area of 190,415 hectares, 19.54 percent is allocated to farmers. The problem is, the Peat and Mangrove Restoration Agency states that the forest in Jadi Mulya village is part of the Sugihan River-Lumpur River peat hydrological unit of 637,000 hectares.

Peat hydrological unit usually takes the form of a swamp area flanked by two rivers. Because of their function as support, the government forbids such areas to be managed, as they are conservation areas. Meanwhile, according to the forestry ministry, forest estate exchange areas are categorized as social forestry reserve areas.

Forestry Ministry’s Director-General of Pollution and Environmental Degradation Control, Sigit Reliantoro, admitted to not having received information on land clearing and creation of canals in the Sugihan River-Lumpur River Peat Hydrological Unit. “It has to be checked whether it’s in the protected area or cultivation area,” he said. He ensured that the forestry ministry has approved Bumi Andalas’ work plan as well as its restoration documents.

Bumi Andalas Permai is not the only company with a concession within a peat hydrological unit. Bumi Mekar Hijau and Sebangun Bumi Andalan also has concession in such areas. Combined, the three companies’ concession areas make up 450,000 hectares, almost the size of all peat hydrological areas combined.

According to Greenpeace Indonesia’s monitoring, canals in the three HTI companies have been spotted since 2000. Via satellite imagery, the environmental organization calculates that the total length of these canals reaches 12,000 kilometers. “Canals are truly detrimental to peat ecosystems,” said Nyoman Suryadiputra, Lahan Basah Indonesia Foundation Senior Advisor.

Greenpeace confirmed that the area has seen seven fires since 2000. The largest fires occurred in 2015 and 2019. “We found a correlation between the increasing length of canals and the intensity of forest fires here,” said Iqbal Damanik, Greenpeace Indonesia’s Forest Campaigner.

As the strongest carbon absorbing ecosystem, peatlands tend to dry when there are canals within them. This is why, in 2016, the government prohibited HTI companies from clearing new land and building canals, which would trigger forest fires. For this reason, the government forbids timber businesses on such ecosystems, even when they are managed through a social forestry scheme.

This report is a collaborative work of Auriga Nusantara, Greenpeace Indonesia, Forest Watch Indonesia, and Hutan Kita Institute, Jaringan Pemantau Independen Kehutanan, Wahana Lingkungan Hidup Indonesia, Eyes on the Forest, Anti-Illegal Logging Institute, Perkumpulan Elang, Kelompok Advokasi Riau with the support of the Rainforest Investigations Network Pulitzer Center.