In a 2020 study, a task force identified the Seaside Cemetery as one of the pieces of critical infrastructure in Blue Hill, Maine, most at risk from rising seas and storm surges.

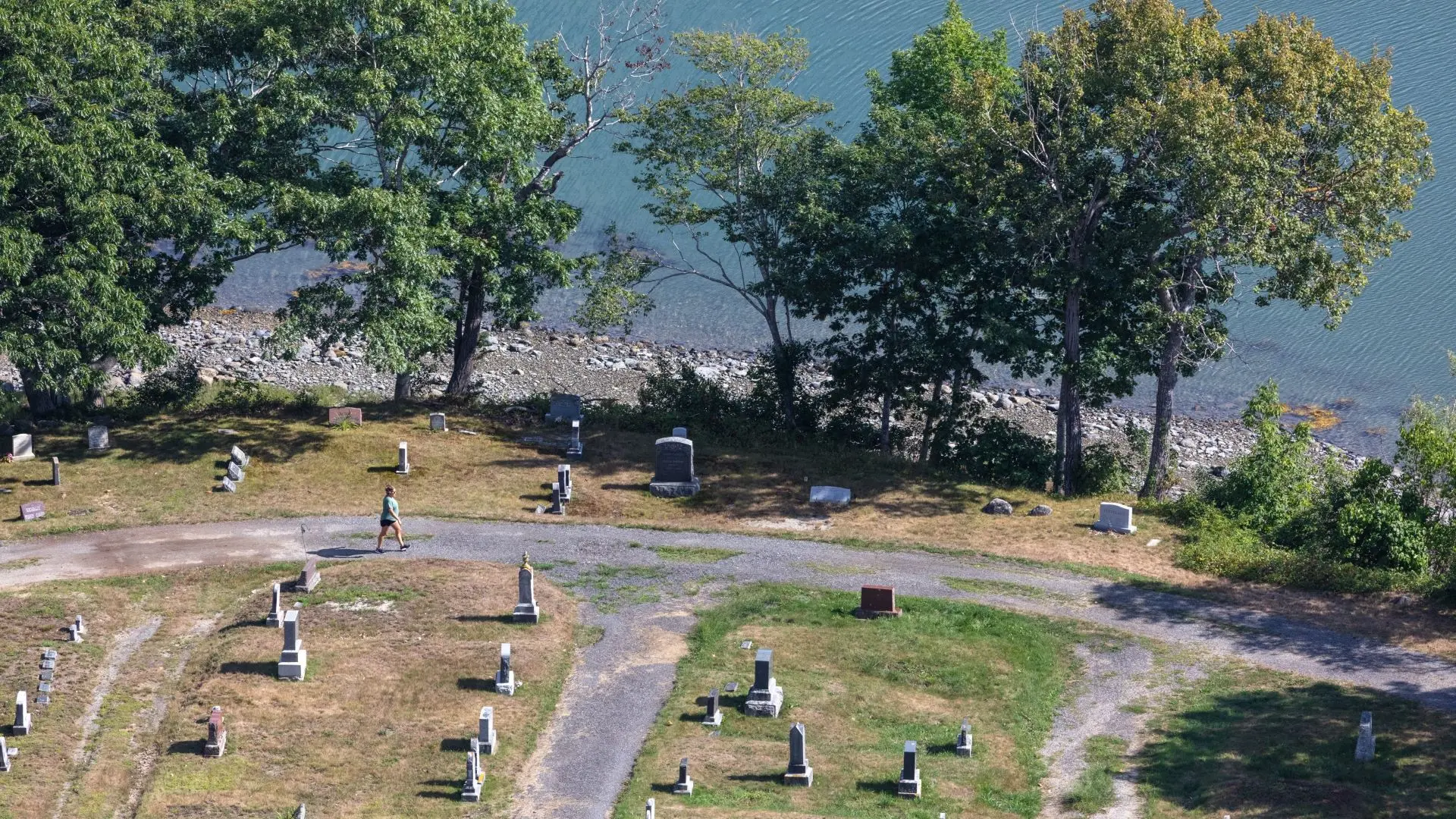

The Seaside Cemetery in Blue Hill is a lovely place to spend eternity. Lying just east of a short smattering of downtown shops, the graveyard is perched on a small finger of land reaching out into the tidal flats of Mt. Desert Narrows, overlooking the rocky outcroppings of Sand and Wiley Islands, popular hangouts for harbor seals and their pups.

As a nonprofit journalism organization, we depend on your support to fund our nationwide Connected Coastlines climate reporting. Donate any amount today to become a Pulitzer Center Champion and receive exclusive benefits!

“It’s a big part of the pace and the rhythm of Blue Hill,” said Brittany Courtot, a schoolteacher and historian who gives tours of Seaside in the summer and fall. Residents walk dogs there, or come to enjoy the view and the quiet. “It’s kind of got this magical quality to it. It’s so peaceful.”

In a 2020 study, a task force identified Seaside as one of the pieces of critical infrastructure in Blue Hill that’s most at risk from rising seas and storm surges. The shoreline bluff it sits on is soft gravel and dirt. Tides have been nibbling away at the base for decades, and increasingly powerful rain events and storm surges have hastened the erosion of the bluff in recent years.

“There are at least two gravestones that seem, within the next year or two, that we really need to move,” said Ellen Best, who serves as chair of the Blue Hill Select Board. There are between 10 and 15 likely at risk within the next decade, said Best.

Of the more than 3,500 former Blue Hill residents buried at Seaside, one of the most at risk in the immediate future is the famous pianist and composer Ethelbert Nevin, who built a sprawling Italianate estate in the area and whose family stayed nearby for generations. “He and his wife are buried almost on the edge. It’s kind of scary,” said Courtot.

Moving a grave can be complicated and expensive, requiring permission from both the municipality and relatives who may have long ago moved away and be difficult to reach. Cemetery budgets are tight, supported by scarce donations and the sale of the occasional plot (the town appropriated just $57,000 for the several cemeteries under its care in 2021), and there is rarely the kind of funding required for anything other than routine maintenance.

And despite their cultural and historical significance, it’s a hard sell to prioritize the interests of the dead over those of the living. The building housing the Blue Hill Fire Department is already experiencing flooding during high tides and storm surges, as is the town landing, and the wastewater treatment facility sits less than a foot above the highest annual tide and is already having trouble with outflow when the water is high. The town expects to spend $5 million on fixes for the plant within the next few years, and around $20 million in total to prepare it to last at least a few more decades.

Adapting “any kind of governmental infrastructure is just hugely expensive,” said Best. “But we really don’t have any choice.”

Convincing residents to spend money preserving cultural and historical sites is often much more difficult. But those sites mean something, not just because they provide a connection to an area’s heritage, said Courtot. Generations of families are buried there, an important touchstone for children and grandchildren, and even those who don’t have family at Seaside get solace from the peace and quiet. “Seaside is pretty central to Blue Hill history and the everyday grind,” said Courtot. “It’s got this energy to it. It’s embedded.”