This project was produced in partnership with KJZZ's Fronteras Desk.

This story is the first of three in a series. In addition, listen to the project's two-part radio series by clicking here.

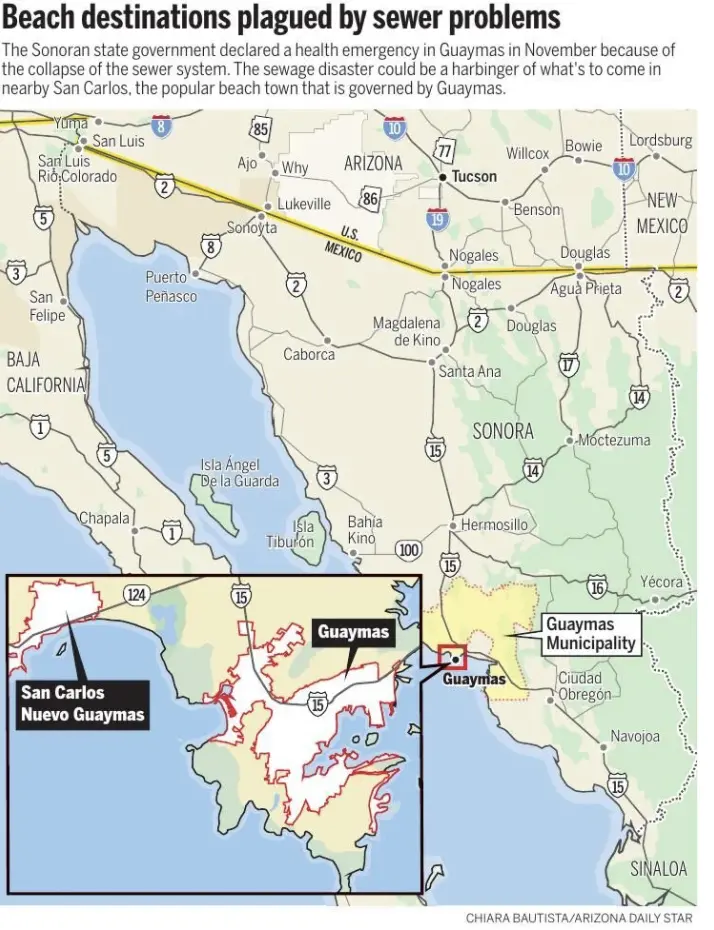

SAN CARLOS, Sonora — On a steamy September day in San Carlos, a popular beach destination six hours south of Tucson, Cotton Cove beach is crowded with picnickers and sunbathers, including U.S. tourists and Mexican nationals.

Located on the upscale Caracol Peninsula, the sandy shore has the feel of a private beach with homes perched on the rocky cliffs and priced upwards of $600,000. The tranquil cove opens into the aquamarine Bahia San Carlos with cactus-studded mountains and the iconic Tetakawi peaks on the horizon.

But to access the cove, beachgoers must follow a stream of sewage bubbling from a manhole cover at the top of the hill and flowing down a stone path to the beach, ultimately pooling near the lapping waves.

As a nonprofit journalism organization, we depend on your support to fund more than 170 reporting projects every year on critical global and local issues. Donate any amount today to become a Pulitzer Center Champion and receive exclusive benefits!

Even during a pandemic, San Carlos is a magnet for tourism, thanks to its unbeatable sunsets, plentiful beaches and outdoor recreation like deep-sea fishing, hiking and kitesurfing.

But as the resident and visitor population swells, its sewer infrastructure crisis is getting worse.

Failed sewage pumps and collapsed pipes send pools of raw sewage onto major thoroughfares and sidewalks, flowing onto beaches and even percolating up into homes.

“It’s worrisome to be so near the smell and sewage,” Gustavo Campoy said in Spanish. The civil engineer lives in Guaymas, the county seat of the municipality that governs San Carlos.

That morning, Campoy had made the 30-minute trip to Cotton Cove beach in San Carlos, eager to show off the gorgeous beaches to friends visiting from Veracruz, on Mexico’s eastern coast.

But due to the sewage leak, they didn’t want to get in the water.

“I didn’t know this kind of thing happened here,” he said.

The situation is even worse in Guaymas, a historic port city with a population of 117,000. Its obsolete sewer system is more than an inconvenience or an embarrassment; it’s an escalating health crisis that has been decades in the making.

In a four-month investigation, in collaboration with NPR-affiliate KJZZ’s Fronteras Desk, the Arizona Daily Star interviewed four former directors of the Comisión Estatal del Agua, which operates the water and sewer systems in San Carlos and Guaymas, as well as environmental scientists and health experts. The Star also spoke with dozens of residents of San Carlos and Guaymas, seeking to understand the root causes, and realistic solutions, to the sewage problems plaguing the region.

The Star also took samples for water-quality testing that showed ineffective wastewater treatment in San Carlos, E. coli contamination on Cotton Cove beach, raw sewage flooding major thoroughfares and fecal contamination of a Guaymas bay.

Sewage exposure poses risks for a host of illnesses, including hepatitis A, giardia and cholera, and creates a breeding ground for mosquitoes carrying diseases like dengue fever. Even when sewage leaks dry out, health risks remain: Pathogens remain in street dust and become airborne, getting into eyes and throats.

In downtown Guaymas, nearly all residents interviewed who live close to sewage leaks reported ailments including vomiting, gastrointestinal distress, sore throats, headaches and stinging or infected eyes.

Guaymas pediatrician Dr. Consuelo Romero said she’s seen a surge in conjunctivitis, which can be attributed to fecal contamination. Children, older adults and immunocompromised people are more at risk of serious illness related to sewage exposure.

Guaymas parents described feelings of powerlessness, anger and despair, having to keep their children locked inside for weeks or months in the summer rainy season, when even a modest rainfall can overwhelm the inadequate sewer system.

Good hygiene is critical in this environment, as sewage splashed on car’s exteriors and onto shoes can easily bring contaminants into homes, she said. Parents must teach children to carefully wash their hands, remove shoes before coming inside, avoid eating street foods and disinfect fruits and vegetables with a chlorine solution, she said.

“If we take extreme precautions, we reduce the risk of getting sick,” she said.

'It's stressful and maddening'

Teresa Cortez

Teresa Cortez hasn’t had a good night’s sleep all summer. The powerful smell of human waste infiltrates her home, at the bottom of a hill in downtown Guaymas.

The stench keeps her awake at night, she said. But worse is the impact on the four grandchildren she is raising.

The kids complain of headaches, stomachaches and stinging eyes. Often, they can’t go out to play due to the smell and swarms of mosquitos, she said.

“It’s not life to live like this,” she said in Spanish. “It’s stressful and maddening.”

One afternoon in early September, Cortez steps outside her yard in the Cinco de Mayo neighborhood, and walks a few dozen meters to reach a natural arroyo that’s running with pungent liquid. Just south of here, the stream will pass the Niños Heroes De Chapultepec elementary school.

Despite the impact on her family, moving from her home of 26 years isn’t an option, she said.

“This is my land, my home,” she said. “And anyway, wherever I go, it would be the same.”

Water utility widely blamed

For at least 20 years, the state water utility, the Comisión Estatal del Agua, or CEA, has failed to comprehensively address what residents have long described as a health emergency.

San Carlos and Guaymas residents report that CEA usually takes weeks or months to address active sewage leaks, if they come at all — and the repairs are almost always a temporary bandage on a gaping wound, residents say.

The politicians who control the water companies’ budgets have little incentive to invest in the infrastructure upgrades required to address the root causes of the sewage issues, former CEA regional directors said.

Repairing or replacing underground sewer pipes doesn’t have the same appeal as announcing a shining new hotel or housing development, said former CEA regional director Marco Antonio Ahumada Gutierrez, a civil engineer with a specialization in hydraulics and a master's degree in business administration. Between 2009 and 2014, he was CEA director for the region covering Guaymas, San Carlos, Empalme and the small Yaqui community of Vicam.

“If you can’t see it, you cannot take advantage of that as a politician,” Ahumada said. “The things that they do, they want people to see it so they can remember it.”

Another major factor: Neither San Carlos nor Guaymas has a wastewater treatment plant, even though experts say the wastewater volume justifies multiple modern treatment plants in Guaymas alone, and a separate plant in San Carlos.

'Help us'

For 40 years, Guaymas resident Julieta Gurrola has lived on a narrow street in central Guaymas, where sewage coated the pavement for most of the summer. Speaking on her porch in late August, Gurrola said she’d had a nasty sore throat and stomach problems, including vomiting, for a week.

“It’s very frustrating because it’s not only outside,” Gurrola said in Spanish. “You can feel it inside, too, from all these days that it has been ongoing, day and night. It’s very constant.”

The sewage in front of her home isn’t the only problem. An arroyo directly behind her home typically flows with rainwater. But for more than two weeks, it has been acrid with the smell of sewage, she said. Standing next to the flow on her back porch, Gurrola gestured to her laundry station, where she hand-washes and hangs her clothes to dry.

“I do it as quick as possible,” she said. “I feel the clothes will get dirty, the smell will get in.”

Gurrola has no desire to move from her home, where she lives with her energetic puppy, Toby. But she said she feels powerless and angry at the lack of attention to the problem.

“It’s maddening because it’s a question of health, more than anything,” she said.

Her message to the state water company? “Help us,” she said.

Health emergency

After a catastrophic summer, the Sonoran state government is acknowledging the extent of the sewage crisis.

In early November, the CEA and the state Infrastructure and Urban Development department, or SIDUR, declared a health emergency in Guaymas due to sewage contamination.

The state of emergency will bring $10 million pesos, about $460,000, in state funding to Guaymas.

Newly elected Sonoran Gov. Alfonso Durazo’s administration is “urgently” working to address the problems, SIDUR director Heriberto Aguilar said in an interview, with plans to replace broken sewage pumps and undertake major sewer-infrastructure projects in Guaymas.

The crisis in Guaymas, with sewage flowing into the bays and flooding city streets for much of the summer, should never have happened, he said.

“The problem is that there was no maintenance of the system, and now we're in a very serious situation,” he said in Spanish. “It’s a crime against nature, and the flow of sewage in the city is an indignity for the people.”

But Aguilar emphasized the health emergency declaration is preemptive, and was issued to avoid reaching an actual health and environmental crisis.

“If we leave more time, that will lead to a health problem,” he said. “We are at the limit.”

'Continuous' discharges

Many Guaymas residents would argue the situation has blown past the limit.

“Crises have already occurred,” said José Arreola, director for the Northwest Center for Biological Research in Guaymas, known as CIBNOR, in an email.

Massive sewage spills in downtown Guaymas have resulted in mandates that outdoor food trucks stop selling street food, he said.

In the upscale Miramar neighborhood of Guaymas, collapsed sewer pipes and broken pumps mean that raw sewage is routinely discharged into the Bacochibampo estuary, which is adjacent to the most popular beach in Miramar, Arreola said.

While sewage spills on roadways and sidewalks can be temporary, and can be cleaned with chlorine solutions, “the contributions of wastewater to recreational beaches are frequent or continuous,” affecting greater numbers of people, he said.

Sewage discharges into water can also result in high nitrogen and phosphorous levels that cause algae blooms, and a lack of dissolved oxygen that kill fish and lead to putrification, said Francisco Zamora, senior director of programs for the Tucson-based Sonoran Institute, a nonprofit focused on promoting conservation and environmentally conscious development.

In Guaymas, “the amount of wastewater has increased and will continue to increase as the population grows,” Arreola said. “If the problem of wastewater spills is not corrected, conditions for a public health crisis remain.”

Boom time for San Carlos

During the pandemic, the formerly sleepy beach town of San Carlos has boomed.

The border closure locked many Mexican nationals out of travel options in the U.S. Eager to escape strict quarantine measures in densely populated cities like Hermosillo and Obregon, many bought or rented vacation homes in San Carlos from which to work remotely.

Hotel and housing developments are underway, and homes for sale are snapped up as soon as they hit the market.

Resale home listings went from about 500 in 2012 to 81 at one point this summer, said Tammi Miller, owner of Vive Real Estate in San Carlos.

Miller, a Silver City, New Mexico, native, has lived in San Carlos since 2006. Back then, the resident population swung between about 4,000 residents in the summer to 8,000 in winter, when American and Canadian snowbirds flocked to the beach for fishing, sailing, kitesurfing, pickleball and live music, she said.

“You get here and you’re young again,” she said. “It’s like summer camp for adults — but in winter.”

'No prevention'

Guaymas native and San Carlos restaurant owner Tomás Thomas said he’s hearing the same thing from friends eager to move to San Carlos.

“Everybody wants a home here,” said Thomas, co-owner of Marvida Taproom and Kitchen.

But while his business is thriving, Thomas has deep concerns about the capacity of San Carlos’ sewer infrastructure.

Over the past 18 months, on at least five occasions, a nightmare scenario has unfolded at Marvida, which opened in 2020.

On the marina-front pathway in front of the brewery and restaurant, manhole covers — stretching from one end of the marina to the other — backed up with sewage.

The last time, in August, sewage even spread onto Marvida’s outdoor patio, Thomas said.

Thomas and his managers shut everything down to clean and disinfect, and tried without success to get the CEA to respond to their reports.

“When we try to reach out to CEA (in Hermosillo), they say, ‘Go to CEA Guaymas.’ We go to Guaymas and they’re like, ‘No, that’s CEA San Carlos,’" he said.

Thomas, who rents the space for Marvida, was able to get help only because his manager’s father is a friend of a CEA administrator. He managed to get a CEA truck from Hermosillo to come clean out the clogs in the sewer system under the boardwalk, he said.

Since then, Thomas said he’s been dreading the next inevitable disaster.

“They don't have a system of fixing it. They just have a system of cleaning it up afterwards,” he said. “There’s no prevention.”

With trepidation, Thomas is watching the frenzy of development in San Carlos, including a new hotel close to Marvida.

“Where’s all that sewage going to go?” he said. “San Carlos is going to collapse that way. It’s already collapsing.”

Sewage Lake

Sierra Vista auto dealer and San Carlos homeowner Bill Lawley was drawn to San Carlos by its natural beauty, deep-sea fishing and small-town atmosphere.

“It was like the old Mexico they sing songs about,” said Lawley, who splits his time between Sierra Vista, Colorado and San Carlos. “How can you beat it?”

Fifteen years ago, Lawley built a home in central San Carlos, just off the main road, Boulevard Manlio Fabio Beltrones. Almost immediately after connecting to the sewer system, raw sewage backed up in the shower, he said.

After weeks without repairs, Lawley hired a worker to install a diversion pipe, redirecting the sewage from his home into the street.

All these years later, Lawley’s desperate fix is still in place — and the problem has only worsened.

The street in front of his home floods with sewage every time the pump up the road breaks down. CEA workers said the construction of a hotel across the boulevard a couple years ago has pushed an unmanageable amount of waste and trash through the old pipes leading to the pump.

When CEA workers clean out the pump, it works for a while — until the next batch of tourists arrive, Lawley said.

“I’d pay a lot of money to not have the sewage lake out in front of my place, but it ain’t gonna happen,” he said. “It’s horrible. That’s just the way it is.”

In late July, a white CEA work truck pulled through the sewage lake and parked alongside the busted pump just up the road.

From inside the truck, Roberto Amador, a 23-year veteran of CEA, said he and his partner were there to get the pump going again. He knew what he’d find blocking the pump, because he’d seen it before: tampons, condoms and other trash.

As expected, the repair was temporary. But Lawley didn’t discover that until his next visit in October.

When he reached his San Carlos home after dark, the night before a fishing tournament in San Carlos, Lawley was greeted by a bigger sewage lake than he’d ever seen. Neighbors told him it had been there for weeks.

Lawley said he’s done with San Carlos and he wants to sell his home, if he can. But he knows that’s unlikely without action from the CEA.

“There ain't no way I could get anybody to buy it the way it is,” he said.

'Embarrassing'

Lawley isn’t the only one suffering. Just next door to the sewage lake is La Calaca Tacos y Cerveza, a popular Dia de los Muertos-themed restaurant that launched during the pandemic.

Before opening La Calaca, co-owner Frank Hernández said he’d been unaware of the extent of the sewage problems in San Carlos. He also owns Sunset Bar & Grill on the north side of town, which has its own septic system.

He noticed the puddle next door to his new property right away.

“At the time, I didn’t realize it was a problem. I thought it was just a puddle,” said Hernández, a Los Angeles native. “It’s rare that the water is not there.”

The reality soon became apparent, especially that first summer when the odor became overpowering. Hernández knows it’s affecting his business: Customers comment on the smell, and it’s hurting his employees’ morale, he said.

“It’s not pleasant, it’s not clean, it’s not sanitary,” he said. “Mainly, it’s embarrassing. We hate to think that people think it’s us, like it’s a personal problem, when it’s a city problem.”

In early November, Hernández said he’s been “continuously” asking the local CEA office for help.

“At first they were very attentive, like, ‘Yes, we’re aware. Yes, we’re going to do something,’” he said. “Now, they don't even want to take our phone calls.”

Hernández said he’s now considering asking neighbors if they’ll all chip in to buy a new pump.

“We’re getting desperate,” he said.

In response to a question about the delay in fixing the problem, a spokesperson for CEA Sonora responded on Nov. 17 that they were in the process of repairing the pump — again.

An infuriating way to live

On a tiny street in downtown Guaymas, three little girls escape the stifling August heat, giggling in an inflatable pool on their front porch. Street dogs lounge in the shade, a few growling lazily.

Mid-block, Rosa Reyes pauses before stepping off the curb into the wet street in front of her home. The street is more like an alleyway, so narrow a single car barely fits, and it’s pocketed with puddles of sewage. This is an improvement over the day before, when the liquid was centimeters deep along the entire road, she said.

For the past four years, ever since CEA workers replaced a 10-inch sewer pipe with an 8-inch pipe, the sewage backups have been a regular occurrence here, she said.

The day before, after making reports to the CEA and waiting for two weeks, Reyes and six of her neighbors showed up at a nearby CEA office, threatening to create a road blockade if they didn’t get help. Reyes believes that protest was the only reason CEA workers finally arrived that morning to unclog the pipe.

Reyes and her husband, Manuel Quiroz Ramirez, disinfect their home daily, cleaning the floor with bleach, aware that their shoes, and their pug Bruno, track sewage into their home each time they enter.

It’s an exhausting and infuriating way to live, especially knowing that the most recent repair is only a short-term patch, Quiroz said in Spanish.

“This is a never-ending story,” he said.

But Reyes is most upset by the impact on her son’s quality of life. Two years ago, her son Christian, now 9, had an eye infection that the doctor said was probably due to the contamination. Now, due to the regular sewage floods throughout the summer months, she doesn’t let him go out much.

“He can’t go out to play,” said Reyes, sitting at her kitchen table as Christian played video games in the living room. “He can’t ride his bike, he can’t go roller skating. He is just sitting on the couch.”

Reyes’ quality of life is diminished as well. She was so sick a few days before with an upset stomach and headache that she was barely standing, she said. She couldn’t eat because of the sewage smell, even with the windows closed — and they are always closed. Otherwise, the smell, and the flies, fill her home.

Tainted cove

Throughout the Caracol Peninsula, the steep hills make for precarious driving and put an enormous burden on sewage pumps at the base of the peninsula, said Jim Straw, a former president of the Caracol Homeowners Association, an engineer by training and a retired commercial pilot.

He and his neighbors often have to hire their own plumbers to repair the public infrastructure. But as a result, even CEA technicians don’t understand the hodgepodge sewer system, he said.

“There’s no standardization,” he said. “Everyone is fixing their own little piece.”

On Sept. 27, a Star reporter took samples of the sewage-soaked sand on Cotton Cove beach, at the base of the Caracol Peninsula. The results revealed levels of E. coli — a type of fecal coliform bacteria — of 7.3 million parts per 100 grams, according to testing done by CIAD lab in Guaymas. Fecal coliforms are the type of bacteria found in the intestines of warm-blooded animals, and they’re often used as a proxy for fecal contamination in water.

That’s the amount you’d expect to find in raw sewage. Mexico’s federal environmental regulations don’t have a specific standard for sand samples. But wastewater must have less than 2,000 fecal coliform parts per 100 milliliters in order to be discharged into the sea or used for agricultural purposes.

Caracol residents say the same sewage leak continued on Cotton Cove beach from late September to late October. The CEA arrived to pump out the sewage in late October, but that was a temporary fix.

Without replacing the broken pump, the waste would just accumulate again in the below-ground tank until it starts spilling again from the manhole cover, Straw said.

When asked about the leak, a spokesperson for CEA Sonora responded on Nov. 17 that they had recently replaced the broken sewage pump with a new one.

While that’s good news, Straw said that doesn’t address the issue that there isn’t a backup pump. The Caracol neighborhood had dual-pump systems in the 1990s, but the CEA took the extra pumps for use in other parts of town, he said.

Without backup pumps, another disaster is inevitable when the new pump fails — which Straw says will happen sooner than it should because the CEA does not do preventive maintenance.

“The pumps are failing at probably 25% of their lifespan because the rotors are constantly regrinding the sand and dirt in the bottom of these pumping stations,” he said.

The lack of long-term planning is another headache, Straw said. When a manhole cover is leaking and the CEA comes to pump out the sewage, they leave before identifying the root cause.

One such leak in Caracol went on for 10 years before the CEA finally opened up the pipes to remove the trash compacted inside, Straw said.

“All of this stuff is simple plumbing and troubleshooting. And there's no impetus for them to troubleshoot it,” he said. “I don’t know that they have the will to do it.”

The sewage problems are becoming even more visible in San Carlos.

In mid-November, an arroyo in a central neighborhood was filled with sewage that poured from a nearby manhole for nearly two weeks, the green flow streaming onto the beach and into the sea.

Mabel Fragozo, who lives nearby, was outraged and posted a video of the sewage river to Facebook on Nov. 15. She’s noticed a sewage flow here for years as she walked her dog, but it has never been this bad, she said. Swimming, snorkeling and fishing are not options for her on this beach.

“The smell is penetrating and constant,” she wrote in a text message.

On Nov. 25, CEA workers finally arrived to suction out the sewage. CEA technician Eduardo Vega said a broken pump was to blame.

Government negligence

When La Calaca owner Hernández moved to San Carlos in 2007, it seemed like he’d found an undiscovered treasure.

“It felt like it was kind of like a secret beach town that no one knew about and that I discovered,” Hernández said. “We’re very privileged to live in a place like this. With the mountains, and the desert and the ocean, it’s gorgeous.”

While the community is filled with people who care deeply about San Carlos, state and local leaders need to step up, Hernandez said.

“San Carlos is growing faster than what they can keep up with,” he said.

Marvida owner Thomas said that without major investment and upgrades, San Carlos will lose its appeal for international visitors.

“It's such a beautiful town — and there’s sewer water in the road,” he said.

Frustration with the government’s lack of attention is growing along with the scope of the problem.

“It’s something so simple, it seems to me,” said Guaymas resident Rosa Reyes. “If the problem is for so many years, just solve it. I don’t understand why they don’t do it.”