Kim Gaither doesn’t drink the tap water in her home. Many of her neighbors don’t either. She sometimes notices a rusty color and sulfuric smells when she runs the faucet, she says.

“Every now and then, I’ll go to wash my hands, and I’ll notice that brown tint,” said Gaither, 59, who rents a house nestled in the rolling hills outside Pittsburgh.

Her city water authority says it’s safe to drink from the tap. But Gaither and other Duquesne residents opt for bottled water, even when brushing their teeth.

Gaither lost her job as a home health aide while COVID-19 ravaged majority-Black communities like Duquesne, where she’s lived since 2018. She fell behind on her water payments during the pandemic, something that never happened when she was working, she said.

On Dec. 15, 2020, the city cut off her water service. For seven days, she walked down the street to shower at a cousin’s house. When she had to use the toilet at her own place, she poured bottled water down the bowl to flush.

As a nonprofit journalism organization, we depend on your support to fund more than 170 reporting projects every year on critical global and local issues. Donate any amount today to become a Pulitzer Center Champion and receive exclusive benefits!

A local nonprofit eventually paid nearly $600 to reconnect her service. Dozens of other Duquesne residents who fell behind on their bills also sought emergency help from mutual aid groups during the first pandemic winter. Some still have delinquent bills.

COVID-19 only worsened a crisis that’s existed for years in financially distressed cities like Gaither’s, where more than a third of the 5,200 residents live in poverty. Utility payments are a heavy burden on these households, and it doesn’t help that the average water bill in America has soared throughout the last decade, likely squeezing low-income communities and people of color the hardest.

Situations like the one in Duquesne can attract deep-pocketed private companies like Pennsylvania American Water, a subsidiary of American Water Works, the nation’s largest investor-owned water firm. Private companies position themselves as a quick fix for small municipalities starved for manpower, expertise, and funding to address water issues. Going private could push bills even higher for communities like Duquesne. Yet the dire state of the nation’s infrastructure means more communities from coast to coast are considering a sale of their drinking water networks.

Duquesne’s tap water could be next. American Water Works is busy acquiring municipal water and sewer systems across the country, and its Keystone State branch has been on a spree the last few years. Pennsylvania American Water already operates in the Duquesne area, supplying wastewater service for the city and adjacent towns. It also controls the drinking water across a swath of nearby cities.

For now, a public utility still supplies Duquesne’s drinking water. But improving the system could cost millions of dollars that the city doesn’t have, said Nickole Nesby, Duquesne’s former mayor, whose term ended in January.

“We should be living better,” said Nesby, 51. “Water shouldn’t be an issue.”

Nesby said she met with representatives from Pennsylvania American Water in November 2020 to discuss the future of her city’s drinking water. The meeting was merely exploratory, Nesby said, noting the city still values the revenue it collects from residents’ water bills. But, she added, they did not rule out future discussions. The company did not comment on the meeting.

Anti-privatization advocates say similar scenarios often result in a sale.

“It’s disaster capitalism,” said Brittany Alston, deputy research director for the Action Center on Race and the Economy. “In these poor communities, specifically Black and brown communities, water systems are up for sale as soon as the community needs money.”

The race to acquire

America’s water industry is a tangled mess of mostly small municipal authorities that operate crumbling pipes. Since the 1980s, federal infrastructure spending has not kept pace with maintenance needs and regulatory compliance, leaving state and local governments with a larger share of the tab. Communities across the nation are now weighing their options, as deferred costs pile up, and local authorities scramble to find modern solutions to their aging infrastructure without raising taxes. It’s unclear how President Biden’s massive infrastructure package will affect their decisions. Private companies tend to swoop in with a tempting offer: a large, one-time injection of funds into city coffers, in exchange for public water or wastewater infrastructure.

Plenty of cities are cashing out. Privatization of the nation’s public water networks has slowly, quietly, accelerated the last few years, according to industry analysts. Up to 15% of Americans pay private companies for the right to flush their toilet or turn on their kitchen faucet—and nearly half these people use networks controlled by a handful of investor-owned behemoths like American Water Works. Private companies acquired over 130 municipal operators since 2015, adding about a million new people to their customer ranks, per market analysis from Bluefield Research.

Most of these recent deals serve small and mid-sized communities: anywhere between 400 to 45,000 people, said Heike Doerr, who studies water utilities for S&P Global Market Intelligence.

“The Philadelphia water system, the New York City water system, they're unlikely to get taken over,” Doerr said. “They have the economies of scale and the technical expertise to manage things like cybersecurity. A smaller city might not be able to allocate the resources to something like that.”

In addition, 14 states, including Pennsylvania, have laws that enable companies to gobble up municipal water and wastewater systems at high prices. Companies can later seek regulatory approval to raise customers’ bills to cover the cost of buying and rehabbing the systems. These so-called “fair market value” laws have helped catalyze deals that are especially attractive for under-resourced communities desperate to keep the lights on in city hall or fund police pensions.

“The legislation enables municipalities to consider selling because they’ll get a larger amount than they would otherwise,” Doerr said.

All this is welcome news for New Jersey-based American Water Works, the leading investor-owned buyer of municipal systems across the country. The company boasts more than 14 million customers, with subsidiaries servicing people in 14 states, most of which have fair market value laws. Since 2010, it’s added hundreds of thousands of new customers to its footprint. It plans to continue buying small and mid-sized cities’ infrastructure, said President and CEO Susan Hardwick at an earnings call in July.

Pennsylvania, where private companies control around a third of the population’s water and wastewater, is ground-zero for municipal buyouts. American Water Works’ local subsidiary here has been leading these takeovers since the state’s fair-market law passed in 2016. At the beginning of September, the firm had closed 10 fair-market deals across the state, adding tens of thousands of new customers, according to public records. The firm says it now serves more than 2 million people in the state.

Its next largest competitor, Aqua America, a subsidiary of Pennsylvania-based water giant Essential Utilities, has also bought up a handful of systems since 2016. Recently, Aqua has met fierce resistance from residents in multiple areas where the company aims to expand, mostly in the eastern part of the state, near Philadelphia. By contrast, Pennsylvania American Water’s buying spree hasn’t attracted as much backlash.

Jennie Shade, head of government relations at the state Municipal Authorities Association, said Pennsylvania American Water is moving at a feverish pace to discuss new deals. “Every other week, I’ll get an email from one of our 700 members. It’s so inundating,” she said. Only a small number of these discussions result in deals, Shade noted.

Pennsylvania is a fitting location for this explosion of activity, since American Water Works has deep roots in the state. In 1886, a pair of brothers in McKeesport, which shares a border with Duquesne, founded the firm’s first iteration, the American Water Works and Guarantee Company, according to an authorized company history published in 1991. In 2017, McKeesport became the site of the state’s first fair-market purchase, when Pennsylvania American Water bought the city’s sewer system for $159 million. The deal included Duquesne and a handful of other small towns that are part of McKeesport’s wastewater network.

Pennsylvania American Water then took over eight more municipal wastewater systems in the state, according to public records. The firm wasn’t a newcomer in some of those towns—it had already controlled their drinking water for years.

This spring, the company completed what it calls the biggest acquisition in Pennsylvania American Water history, paying $235 million for the sewer system in the city of York, which serves nearly 14,000 people, plus another 30,000 in surrounding towns connected to the network. The deal closed despite a rare showing of opposition from those surrounding towns.

Doerr, the S&P analyst, said wastewater is a relatively new focus for acquisition-hungry private water firms. In Pennsylvania, most municipal takeovers now involve sewer systems. American Water has acquired just one city water system in Pennsylvania under the state’s fair-value law, according to public records.

If Pennsylvania American Water were to seriously court Duquesne, the city council—not the mayor—would ultimately decide whether to sell. Multiple council members did not respond to inquiries about whether they’d been approached by the company recently, or if they’d consider such a proposition.

Higher and higher bills

After the city of Duquesne turned Kim Gaither’s water service back on, she continued missing payments. The pandemic was still raging, and Gaither hadn’t returned to work. By the fall of 2021, she owed hundreds of dollars. The city shut off her water again. This time, the cutoff lasted weeks, until she got help from family and paid off her balance, she said.

During that time, Gaither said she also fell behind on her sewer payments to Pennsylvania American Water. The company never shut off her service.

Whether Gaither is paying a public or private utility, those bills are her largest expense after rent, she said. Private service does tend to be more expensive than public, according to the U.S. Government Accountability Office. In 2016, Food and Water Watch, an anti-privatization advocacy group, surveyed the 500 largest community water systems across the country and found that Pennsylvania households hooked up to private systems paid 84 percent more than they would for a municipal supplier—that’s $323 more a year, the report said. A similar analysis published this year in the journal Water Policy found that Pennsylvania has some of the highest water bills of any state.

But affordability studies have largely overlooked how rising costs affect communities of color specifically, according to a 2019 report by the Thurgood Marshall Institute at the NAACP Legal Defense and Education Fund. The report’s authors noted, however, existing research indicates that Black communities may pay more for water services, or that those services may eat up a larger share of household incomes. Residents in Black communities might be more likely to experience shutoffs, the report also found.

Officials in Duquesne said that many residents had trouble keeping up with their bills before the pandemic.

The Pennsylvania Public Utility Commission approved Pennsylvania American Water’s request to raise its statewide rates on water and wastewater customers during the pandemic. Last year, sewer bills for the McKeesport system, which includes Duquesne, shot up 38% ($19.82) at a time when residents like Gaither were still unemployed due to COVID-19. In January 2022, another rate hike went into effect for Pennsylvania American Water customers. In Duquesne, that meant raising wastewater bills another 11%, according to Pennsylvania American Water spokesperson Gary Lobaugh.

Lobaugh said the company seeks to raise rates after investing vast sums of money into ailing systems. When the firm bought the McKeesport sewer system in 2017, it promised not to hike rates for at least a year. It then set to work replacing service lines in the area, to the tune of $42 million, according to Lobaugh. Other networks the company owns across the state also needed rehabbing, he said.

After a string of costly rehab jobs in other states, American Water Works is now seeking rate hikes in those places, according to a research note S&P’s Doerr published this summer. The company has also requested yet another rate increase in Pennsylvania this year, and regulators are currently holding hearings on the proposal.

Duquesne’s aging drinking water infrastructure likely needs a costly revamp—whether the system gets bought out by a private company or not. Longtime residents say they remember better-tasting water in their youth.

“Old systems tend to produce water that doesn’t taste or look very good,” said Myron Arnowitt, the Pennsylvania director of the Clean Water Action advocacy group. He noted that Duquesne’s water department purchases drinking water from a municipal supplier in another county, about 20 miles away. “The farther away you are from the treatment plant, the more problems you’re going to have,” said Arnowitt.

In addition, the city’s infrastructure was designed for a larger population. Half the residents have left since U.S. Steel closed its Duquesne mill in 1984. Abandoned homes covered in ivy, doors ajar, are visible all over town. Under the potholed streets, water meant for drinking sits around in pipes for long periods of time, waiting to be used. When it sits too long, the chemicals used to treat it can create harmful byproducts.

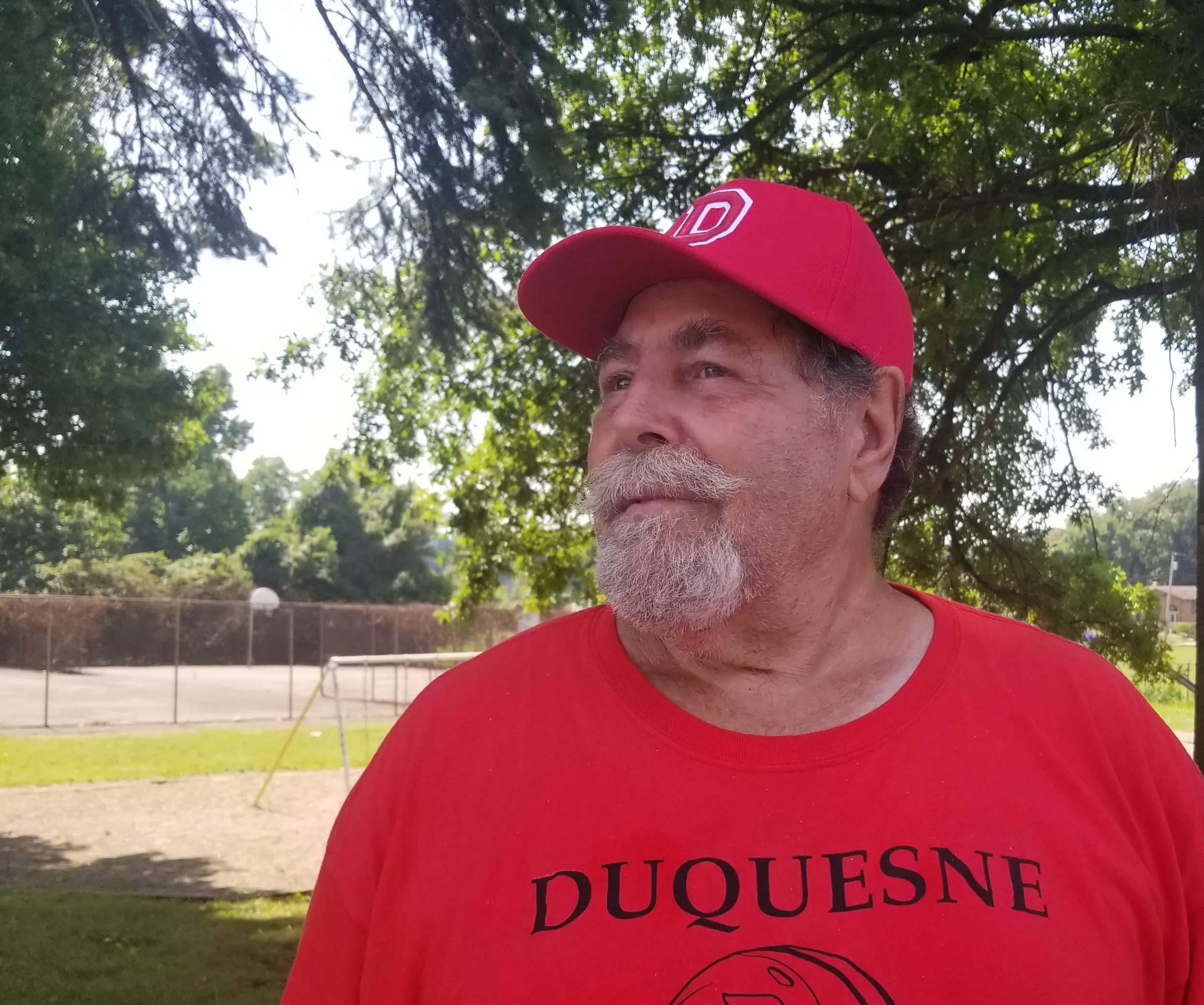

Duquesne’s water has high levels of several potentially harmful toxins, according to research by the Environmental Working Group, an advocacy organization. Water systems in the surrounding region do too, possibly from fossil fuel extraction and other industries in the area, said Arnowitt. Though the water in Duquesne is technically in compliance with legal drinking standards, many residents don’t use it for much besides bathing. One local said he drives to a natural spring in a neighboring town to collect water by hand. “I prefer to drink the spring water,” he said.

Looking to the future

Academics who study water systems caution cities against rushing to sell their infrastructure when it’s failing or when their public authority performs poorly.

Communities that form a cooperative water utility, for example, can retain control of their water system, democratically elect those in charge, and keep prices low by operating at cost and accessing cheaper forms of capital than a private company would, said Melissa Scanlan, director of the Center for Water Policy at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee. Cooperatives are often overlooked as an option, she said.

“The debate is unnecessarily bipolar, going between either public or private and not thinking about this other model of cooperative governance,” said Scanlan.

Duquesne’s new mayor, Richard Adams, who oversaw the city’s water department in his previous role as council member, did not respond when asked whether he’d considered forming a cooperative or selling the system.

Karl Russek, a researcher at the University of Pennsylvania’s Water Center who advised Duquesne officials on their water issues before the pandemic, said the city should spend big to fix the system and hire new experts to run it. Or it should consider merging its water operation with an adjacent municipality. Neither is likely to be popular, he said.

The same debate is raging across many cities. “There will be a reckoning in the next 10 years in the state of Pennsylvania, as these systems start to age out of their viability,” Russek said.

Mayor Adams said his city is planning to replace old pipes and equipment at pump stations, but he did not say when the projects would take place or how they’d be funded, and he did not state exactly how much of the city’s system would be affected.

Russek said cities that invest heavily in their water systems may need to hike rates to cover those costs.

“This is infrastructure that was funded largely by grants in the ‘70s and ‘80s,” he said, adding, “cities are trying to figure out how to catch up from 30 years of deferred maintenance.”

The Biden administration’s infrastructure package could provide help. The measure allocated tens of billions of dollars for water and wastewater systems. It also purportedly set aside a portion for economically disadvantaged communities. Last summer, American Water Work’s then-CEO Walter Lynch said the infrastructure deal won’t thwart the company’s expansion plans. The measure is merely a “drop in the bucket compared to the overall spending that's necessary,” Lynch said during an earnings call.

Fawn Walker-Montgomery, 42, served on the McKeesport town council that approved the sewer sale in 2017. She voted for the deal because the city needed the money at the time, she said. But privatization didn’t solve their problems. “We’re still in desperate need,” she said. If she could do it over, she’d push Pennsylvania American Water to help the community more, she added.

Walker-Montgomery now runs the nonprofit that paid to reconnect Kim Gaither’s water last year.

Pennsylvania American Water, for its part, offers payment plans and grants for low-income residents. Multiple Duquesne residents said people in town simply don’t know these programs exist.

When Mayor Adams took office, he told a local news blog he planned to pursue delinquent water bills in Duquesne. In an email, he explained that the city issues a warning notice prior to shutoffs and encourages residents to set up a payment plan.

Gaither remembers receiving delinquency notices from the city. But when she called the phone number listed, they did not discuss a payment plan, she recalled. She kept waiting—for the pandemic to end, for her job to come back.

In January 2022, the state announced a new grant program to help low-income residents avoid water and wastewater service shutoffs, in response to pandemic hardship. Early in February, Gaither received a grant to help pay her utility bills. “It’s a blessing,” she said.

In the spring, with hopes that the worst of the pandemic was over, she decided to return to work.

Though she said she was optimistic about her life getting back on track, she could soon be struggling with her utilities once again. If Pennsylvania American Water secures another rate increase, her sewer bill may rise for a third time since the pandemic started. And she might see higher water bills whether the city of Duquesne fixes its pipes on its own or sells its water system to a private company.