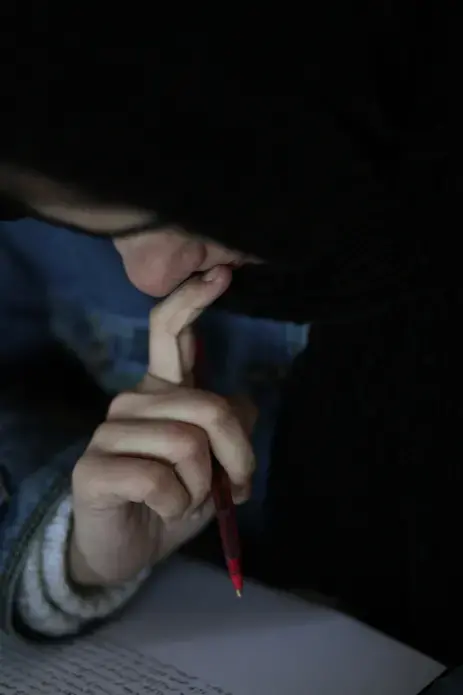

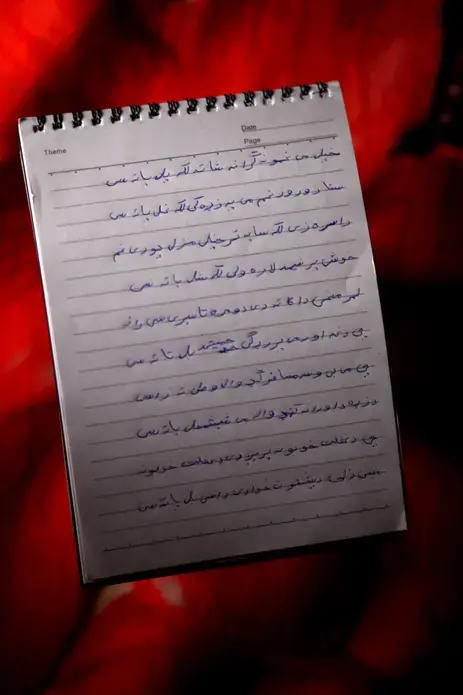

Pashtun poetry has long been a form of rebellion for Afghan women, belying the notion that they are submissive or defeated. But writing poetry is dangerous for many Afghan women and girls. Its classical subject — love — in almost any form is taboo. It threatens to be evidence of an illicit relationship.

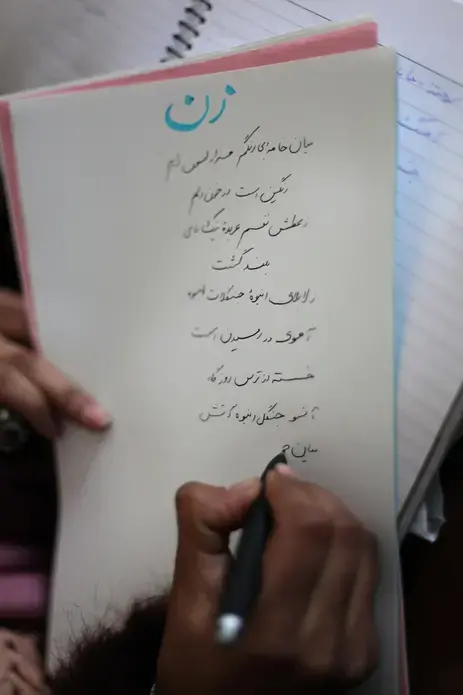

Landai are two-line folk poems that can be funny, sexy, raging or tragic and have traditionally dealt with love and grief. The word landai means "short, poisonous snake" in Pashto. The poems are collective — no single person writes a landai; a woman repeats one, shares one. It is hers and not hers. Although men do recite them, almost all are cast in the voices of women. "Landai belong to women," said Safia Siddiqi, a renowned Pashtun poet and former Afghan parliamentarian. "In Afghanistan, poetry is the women's movement from the inside."

They often rail against the bondage of forced marriage with wry, anatomical humor. An aging, ineffectual husband is frequently described as a "little horror." This is from Gulmakai, a 22-year-old woman in Gereshk, Helmand Province.

Making love to an old man is like

Making love to a limp cornstalk blackened by fungus.

"I know this is true," she announced. "My father married me to an old man when I was 15." She said she made up poems all the time, as she cooked and cleaned the house.

But Afghan women have also taken on war, exile and Afghan independence in poetry.

Lima Niazi, a 15-year-old Pashtun woman in Kabul addressed her latest poem to the Taliban:

You won't allow me to go to school.

I won't become a doctor.

Remember this:

One day you will be sick.

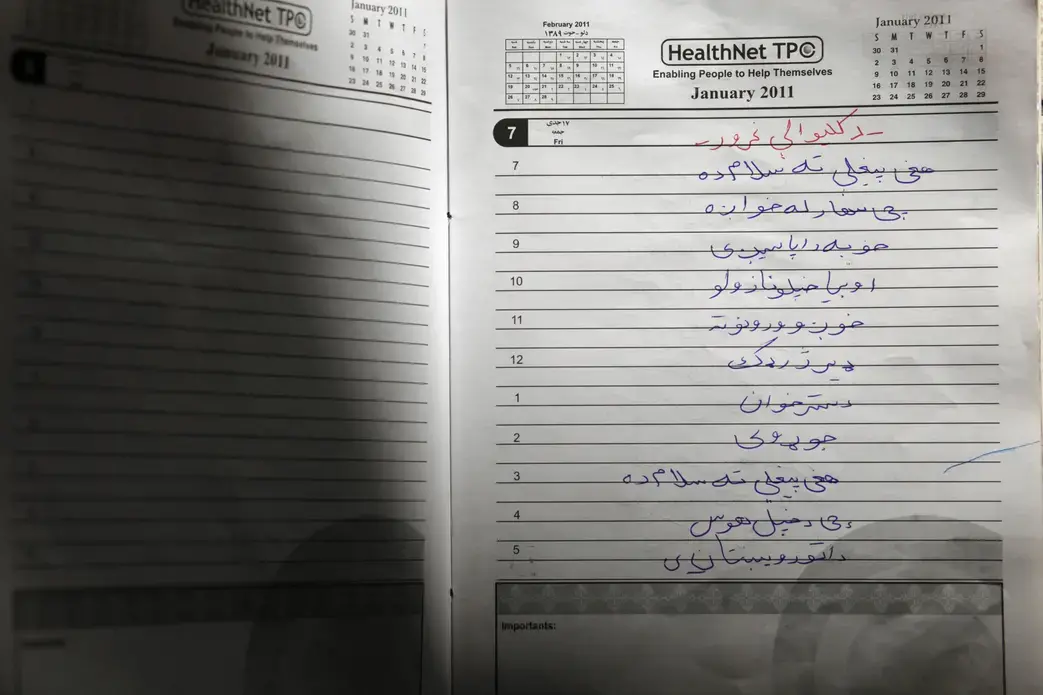

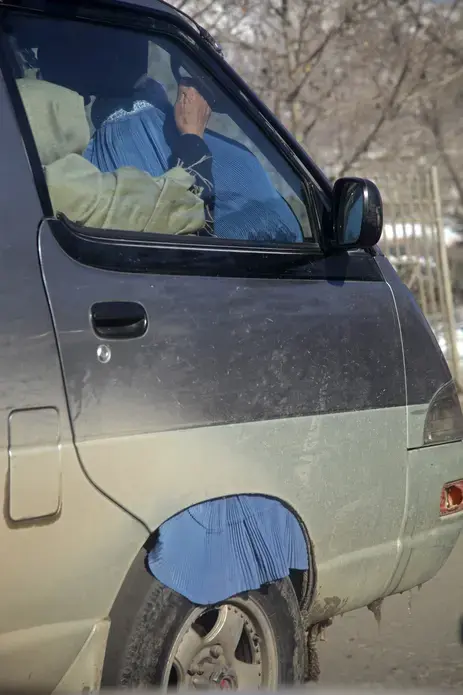

Mirman Baheer is Afghanistan's largest women's literary society, and in Kabul has more than 100 members drawn primarily from the Afghan elite: professors, parliamentarians, journalists and scholars. They travel on city buses to their Saturday meetings, their faces uncovered, wearing high-heeled boots. But in the outlying provinces — Khost, Paktia, Maidan, Wardak, Kunduz, Kandahar, Herat and Farah — the society's members number about three hundred. In rural areas, Mirman Baheer functions largely in secret. Many of the rural members have to use mobile phones to participate at meetings, calling whenever they can, often at great personal risk. They read their poems to the group by phone and these are then transcribed line by line. To conceal poetry writing from their family, they rely on pen names.Traditionally women writing poetry is seen as shameful and could result in a beating or even death.

Of Afghanistan's 15 million women, roughly eight out of 10 live outside urban areas, where U.S. efforts to promote women's rights have met with little success. Only five out of 100 graduate from high school, and most are married by age 16 with three out of four in forced marriages.

Meena Muska (Meena means "love" in the Pashto language; Muska means "smile") lost her fiancé last year, when a land mine exploded. According to Pashtun tradition, she must marry one of his brothers, which she doesn't want to do. She doesn't dare protest directly, but reciting poetry allows her to speak out against her lot. She has written:

My pains grow as my life dwindles,

I will die with a heart full of hope.

Zarmina, who committed suicide two years ago, described "the dark cage of the village." Her poems posed questions: "Why am I not in a world where people can feel what I'm feeling and hear my voice?" She asked: "In Islam, God loved the Prophet Muhammad. I'm in a society where love is a crime. If we are Muslims, why are we enemies of love?" Zarmina is to the women of Mirman Baheer the most recent of Afghanistan's poet-martyrs.

"She was a sacrifice to Afghan women," says poet Ogai Amail and organizer Mirman Baheer. "There are hundreds like her."