“And the Oscar goes to […]” not Anna May Wong, who lost out on one of the only lead roles for an Asian woman in 1937’s The Good Earth. Rather than choosing one of the only and the most well-known Chinese American actress to play the part of a Chinese woman, the film’s directors chose white actress Luise Rainer to act in yellowface. Rainer would go on to win the Oscar for Best Actress in a Lead Role while Wong ended up taking a break from Hollywood and leaving the United States for several years.

As a nonprofit journalism organization, we depend on your support to fund journalism that addresses the crisis of institutionalized racism in America. Donate any amount today to become a Pulitzer Center Champion and receive exclusive benefits!

Wong’s story with The Good Earth is not unique, nor was her treatment in Hollywood. Many other Asian actors, like silent film icon Sessue Hayakawa, were forced to play roles based on racial stereotypes while the more nuanced roles were given to white actors, even if the part was written for an Asian person.

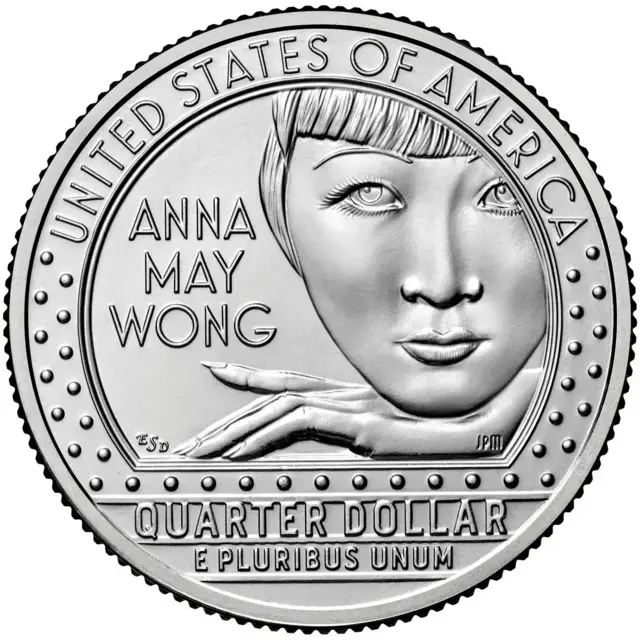

However, in 2022, the U.S. Mint released a commemorative quarter featuring a portrait of Wong, and with this came a wave of renewed interest in her and her story. The quarter is part of the American Women Quarters series that honors the accomplishments of women from different fields. Wong is the first Asian American to be featured on U.S. currency.

For many students and professors of Asian American film, it was a sign that, finally, people had started to recognize what they believe has long been an overlooked part of American film history. For them, the commemorative quarter was just one small part of what is a larger effort to provide recognition and representation to Asian American communities and their stories. Dr. Brian Hu, a film professor and artistic director of the San Diego Asian Film Festival, referred to it as “a fight against invisibility.”

Hu explained that, before the 1970s, there were not a lot of “Asian American filmmakers very self-consciously making films sort of by and about [Asian Americans].” Before that, Asian American film was very difficult to identify, and he describes it as works “directed mostly by white men, but that kind of engage Asian American communities or characters.”

Although Asian American actors have been starring in films since the beginning of Hollywood, pinning down the idea of “Asian American film” is a much more difficult endeavor. Much of this has to do with the role that Asian Americans and their treatment has played in the larger history of the United States.

Asian culture is often homogenized, so pinning down what exactly makes something part of “Asian American culture” is complicated. Today, it is a little bit clearer, with films like Crazy Rich Asians and The Farewell—which are directed by, written by, and star Asian American actors—becoming popular. However, there were very few Asian American directors and producers in the early days of Hollywood, and therefore “Asian American film” is not really able to be defined.

Rather than trying to define Asian American film history, Hu prefers to think of it as “proto-Asian American cinema,” or early films that starred Asian American actors, even if they were written and directed by white people. He includes examples such as “actors like Sessue Hayakawa [who] didn't necessarily get a chance to direct their own films or work with Asian American directors, but they were Asian American characters and faces in all these movies.”

One of the reasons the study of Asian American film has been hindered in the past is because “filmmakers or critics, scholars [...] didn't like the work of Anna May Wong or others of that time, because inevitably they starred in a lot of racist movies because they had no control over their own narratives, or at least not the kind of control that we might see today.”

Hu’s work aims to redefine how Asian American film is considered today and introduce it to a new generation. Though he acknowledges that the general public still doesn’t have much of an interest in Asian American films, he believes it is still important to fight against the victim narrative and instead explore ways that Asian culture in Hollywood has been used positively, as well as the triumphs of past Asian Hollywood stars.

The story of Wong in The Good Earth is one of the most important illustrations of why Asian American film still needs to be studied. Wong’s triumph and her comeback should be considered just as important as the discrimination she faced, according to Hu.

Similarly, many people know about the discrimination that Hayakawa faced as a Japanese man during World War II, but few know about his efforts to produce his own movies and tell his own story. Rather than adhering to the victim narrative that has been pushed onto Asian American actors and filmmakers, the work that Hu does aims to shed a light on the triumphs that the community experienced.

Jaimie Baron, a media theorist and professor of cinema studies, suggests that the move toward recognition in Asian film is part of a larger “racial reckoning" that is bringing about a new interest in the history of various popular forms of media, especially those centered around racial minorities.

There is “more funding because of social changes” when it comes to examining cultures of the past and getting the word out. This comes in the form of documentaries, podcasts, and books, among many other media. Baron wants to differentiate between a “zeitgeist as opposed to a concerted effort.” Although she believes there has been a shift in the general American culture in terms of how the general public views race and the past, she wishes to attribute more of the progress to a “new effort to focus on underrepresented groups.”

Part of this is also due to the prevalence of social media in our current society. Baron claims that “people have access to share and look for new information in the social media age.” Although this can allow misinformation to spread, it also allows for older stories to be told in a new light, with a fresh perspective, because “until the 1950s, history was the history of powerful, mostly white men,” according to Baron.

Part of the goal of many of the efforts occurring today are to not only bring visibility to Asian American films of today, but also to retell old stories of Asian American actors and celebrate their accomplishments in a world and a time where they were not widely accepted.

The San Diego Asian Film Festival, and other Asian film festivals, is one of the biggest ways that Asian American film can be widely distributed and appreciated, according to Hu.

“We need to celebrate Asian American films that are not studio movies,” Hu said. “So that means documentaries. That means experimental films. That means indie films by directors we don't know about anymore. Films that are out of print. Films that never really could circulate to begin with [...] but that doesn't mean that these movies don't exist.”

In addition to helping direct and curate the San Diego Asian Film Festival, Hu also works on a podcast titled Saturday School. The podcast is meant to “teach your unwilling children about Asian American pop culture history” as Hu and his co-host, Ada Tseng, “dig up some of their favorite works they've come across covering Asian American arts & entertainment over the years.”

Hu explains that “every episode we dedicate to a film from Asian Americans, very often films that are very hard to find, and they're not part of the conversation anymore. And so this is our way of bringing it back.”

He elaborated: "We leave these breadcrumbs so if you really wanted to watch [these movies], there are ways to watch them. A lot of Asian American films, their licenses have expired and nobody has thought to renew them, and therefore you can't buy them on Kanopy (a video streaming service). So yeah, leaving those breadcrumbs says, ‘If you care enough you are here are the ways you can find them.’”

Robin Means Coleman, a professor of communication studies and author of Horror Noire: A History of Black Horror, has experience with exploring the depiction of racial minorities in film in both a historical and contemporary context. Her work is focused on reclaiming a genre in order to understand the nuances of the current and historical social climates.

“If you follow the disciplinary thread, rather than the racial thread, then you see it's a sort of outreach that is driven by pedagogy. [It says] here's another way to understand our social world. And I think that we need as many of those tools in our tool belts.”

Her work is “absolutely driven by the principles of diversity, equity, and inclusion. It was very much driven by the principles of social justice and belonging. It's helpful for everybody to understand their histories so that we understand how we came to be and treat each other. And more information about relationships can help foster and cultivate better relationships.”

One of the biggest hurdles that many people who are interested in film history where it concerns racial minorities is that it can often be difficult for people who are not part of these communities to understand the importance of representation in the past and present. Hu emphasizes the importance of understanding Asian American film history in the wider context of American history, and why Asian people everywhere can take pride in these actors.

“It helps to have heroes, and movie stars can play that role. You can be able to look at Anna May Wong and you don't immediately think about racism in Hollywood. You don't necessarily think about the Chinese Exclusion Acts.”

While those are, of course, wrapped up in the reality of Wong, Hu hopes that the first thing people see when they look at her is, “Wow, what a star. Look at her wear those clothes. Her acting can stand up to Marlene Dietrich in Shanghai Express. And that is a kind of sign, a feeling of joy and a kind of pride.”

He acknowledges that “the people who are going to have that kind of pride are Asian Americans themselves. We can’t expect non-Asian Americans to take pride in Anna May Wong the way that it's in our bones.”

“Is that as important as talking about the Japanese incarceration?” he wonders. “Well, we should be talking about both together. We should be talking about victimization because those are concrete facts and these are the stains on our history. But we would like a demand for more and perhaps even to inspire activists and scholarship. This work moves me and I want the world to see it. So I think that's a welcome change. And even something as seemingly superficial as Anna May Wong on a quarter can perhaps inspire that.”