The chief and the council of Canada's Attawapiskat community declared a state of emergency in early April after a wave of suicide attempts forced members to reevaluate the issue of communal mental health, according to a recent New York Times report.

Since September 2015, 101 people—or 5 percent of the population—have attempted suicide in the Attawapiskat First Nation, leaving bystanders in desperation and disbelief as they struggle to break this trend of self-destruction.

Attawapiskat's high rate of suicide attempts is not a new phenomenon and the small aboriginal community of 2,000 residents is not alone in its rising surge of destructive behavior.

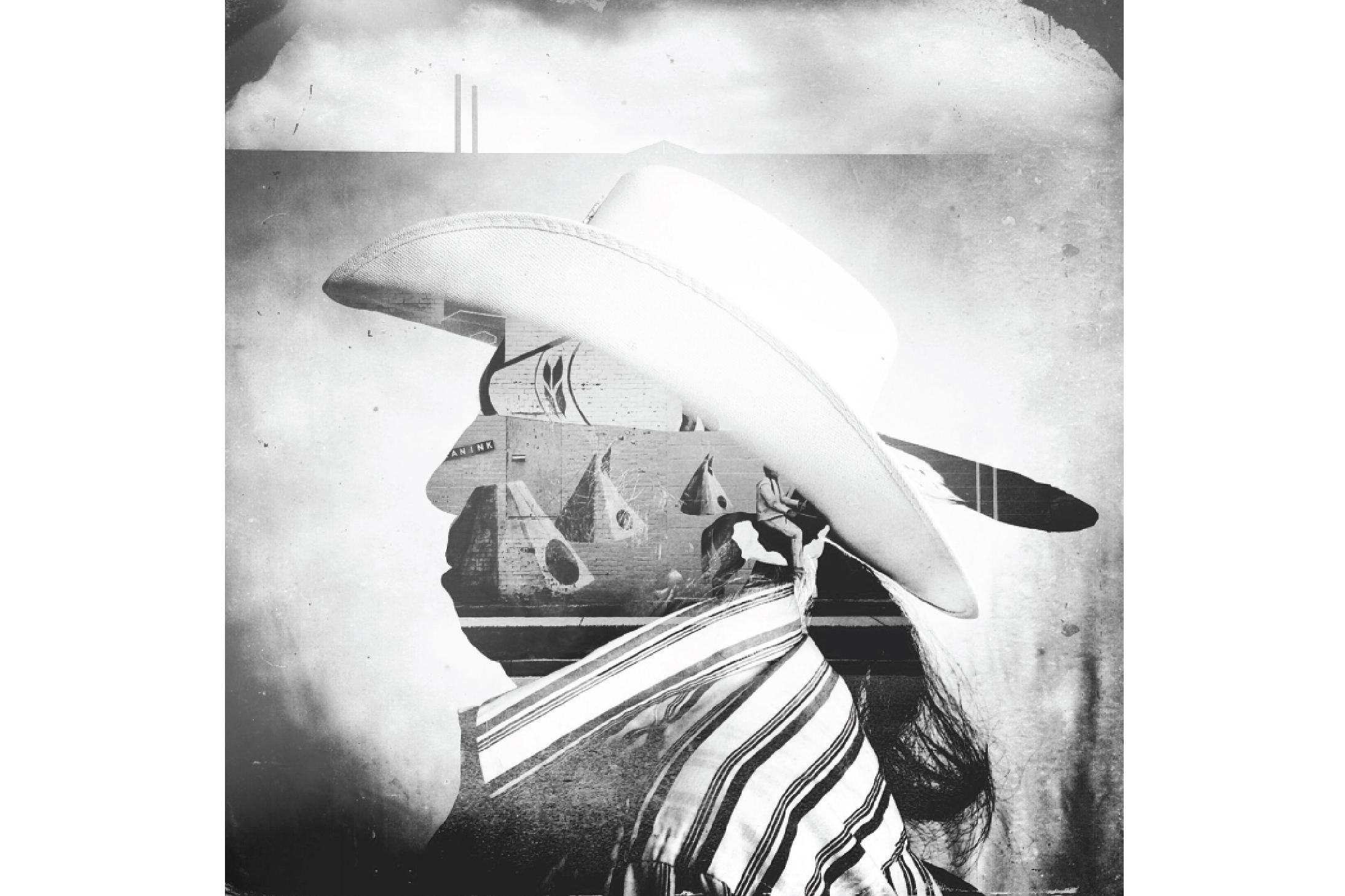

While reporting on the effects of Canada's residential school system for her Pulitzer Center-supported project "Signs of Identity in Canada's First Nation," grantee Daniella Zalcman learned that a disproportionate number of First Nations people engage in high-risk behavior including drug abuse, alcoholism, violence and unprotected sex. She also discovered prevalence rates of HIV in Canada's indigenous groups were 5-10 times higher than in comparable populations in Australia, New Zealand, or the United States.

"There's just so little regard for their own behavior," Zalcman told the Pulitzer Center. High-risk behavior—which often results in suicide—is a symptom of bigger problems that involve inter-generational abuse and mental health struggles within the community.

Similarly, Guillaume Saladin, featured in film Circus Without Borders, noticed the prevalence of depression and suicide in his Inuit community of Igloolik in Nunavut, Canada. As a result, he decided to open a youth center and start a circus called Artcirq where community members could express their feelings in a safe manner.

"They feel stuck in time, so they stop thinking right. They don't have a clear vision," Saladin said. "[The circus] opened the minds of the people in Igloolik that if they believe something and are ready to put their minds to it, it's possible."

Zalcman and Saladin agree that the lack of self-esteem and loss of purpose in First Nation communities stems from a history of repression and cultural genocide that is reminiscent of a time when Canada implemented the residential school system in the 19th and 20th centuries, forcing young indigenous students to assimilate into western Canadian culture and forgo their own ethnic identities.

"There is a huge correlation between loss of self-identity and self-destructive behavior," Zalcman said, explaining that many of Canada's indigenous people continue to feel disempowered.

In order to heal the past wounds of neocolonialism and reverse the ongoing trend of self-destruction, Saladin said First Nations members must learn to trust themselves, their communities and the Canadian government. He hopes more communities will recognize the importance of implementing safe spaces similar to Artcirq where individuals can express their grievances, recognize their talents and follow their dreams.

"To address the issues and challenges that Northern communities are facing today, we need more projects like [the circus]," he said. "Projects where trust, identity and dignity are at the center."

Zalcman said it is also important to educate people about Canada's past cultural genocide in order to help heal the loss of identity experienced by many First Nations individuals.

"This is very much a part of history that's left out of history books," she said. "It's shameful and embarrassing." Zalcman said she hopes her upcoming book will become part of the Canadian school system curriculum, giving students the opportunity to learn about the issue. "If my work doesn't create change, I'm in an existential crisis of 'What am I doing?' I want my work to be effective in policy and education change."

Project

Nunavut, Canada: Hope on Ice

In the remote northern reaches of one of the wealthiest countries of the world is an aboriginal...