180 sixth, seventh, and eighth grade students from Washington, DC sat forward at the American Film Institute (AFI) Silver Theater in Silver Spring, Maryland as Susan Gray, director of the Pulitzer Center-supported documentary film Circus Without Borders, introduced a screening of the film.

“I hope that you will leave this screening somehow changed,” said Gray. “That’s part of why we made this film.”

The students from Creative Minds and Eliot Hine Middle School in Washington, DC had heard a little bit about the film beforehand. Pulitzer Center staffers Fareed Mostoufi and Meerabelle Jesuthasan had visited their classrooms the week before the screening to give them a sneak preview of what their field trip would contain, and to discuss the more technical aspects of the documentary-making process. This pre-field trip visit was part of a three-part visual storytelling workshop supported by the D.C. Commission on the Arts and Humanities. As part of these pre-screening workshops, students learned that the two people at the center of the "Circus Without Borders"—Guillaume Saladin, founder of Artcirq in Arctic Canada, and Yamoussa Bangoura, founder of Kalabante in Guinea—were the film’s ‘subjects.’ They learned that documentaries follow subjects who are facing conflicts, and that filmmakers use audio (A-roll) and images (B-roll) to share how the film’s subjects are navigating conflicts. Students watched the film’s trailer to identify the main conflicts that Yamoussa and Guillaume would be facing in the film. They then tried to figure out whether the B-roll they were seeing were action shots, exposition shots, or archival footage. The goal: to introduce students to ways of telling stories like filmmakers, a week before they would actually meet the filmmakers and subjects who made “Circus Without Borders.”

On the day of the field trip to AFI Silver Spring, students were first welcomed by Stephanie Hartman, AFI Theater’s Director of Education Programs. After Gray’s introduction, the lights dimmed, the children whispered and settled into their seats, and the movie began. Students watched the gleaming white sheets of Arctic ice, then the dusty heat of Guinea. They heard West African drumming and Inuit throat singing. They laughed and gaped at the endless acrobatics. They listened, intently, to the film’s subjects talk about how their art was helping people in their community—to heal from suicide, to find a home, or to support their family.

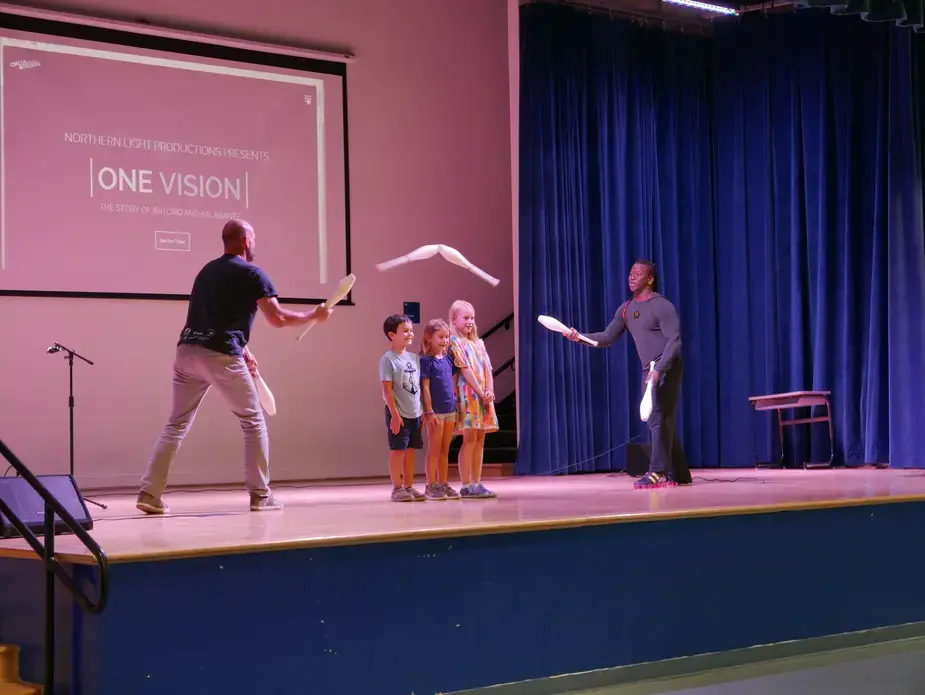

When the lights came back on, voices began to rise again. But soon, students began shushing one another, as a man began walking across the stage and through the audience while quietly playing the kora, a traditional Guinean string instrument. It took the students very little time to realize that this was none other than Yamoussa Bangoura himself.

Guillaume Saladin joined him too, and soon, they were juggling and doing flips. This was the first week they were performing together again after a year apart, but their coordination was seamless. The students watched, entranced.

With silent gestures, Saladin asked for two volunteers. Hands shot up immediately, and a lucky pair scrambled onstage.

“Do you trust me?” asked Saladin. They nodded. Saladin and Bangoura positioned the middle schoolers to stand straight between them. Then, they started to juggle.

Saladin and Bangoura tossed the pins to one another in easy motions, right across the faces of middle schoolers standing stock still. In the audience, their classmates gasped and shrieked, covering their faces and peeking through their fingers. After about 30 seconds, they stopped, and the volunteers were welcomed back to their seats with rousing cheers.

The performers then asked their audience to consider what had just happened, and how they had felt during the performance. “Nervous,” one student answered, explaining that she was nervous that someone would be hit with the pins.

“Excited,” another student replied. Many nodded in agreement.

Saladin and Bangoura asked the students to think about what had produced those feelings: Had they met before? Had they known who Guillaume and Yamoussa were before watching the documentary they had just seen? How, then, had they managed to make them feel so much in just a few minutes of an almost wordless performance?

“That is the power of art,” Saladin explained.

The audience then reflected on what they had seen. In the film, they saw Saladin and Bangoura build their life’s work—for Saladin, that was ArtCirq in the Canadian Arctic, and for Bangoura, it was Kalabante in Guinea. Through both, the performers tried to better lives in their communities through circus. They were trying to create change through art—just as the filmmakers had wanted to change these students’ lives through their documentary.

While the acrobats talked about the role of art in making change, they acknowledged the film and the people who had brought them there. “It’s not just me and my acrobatics, it’s not just Bangoura,” said Saladin. “It’s a team that makes this happen.”

He told the story of how they had gotten here today, to talk and perform for the students of Creative Minds and Eliot Hine Middle School. Had it not been for "Circus Without Borders," he would not have met any of the students there today, or the over 500 students at five other schools that the team was scheduled to see that week.

Susan Gray and producer Linda Matchan joined Saladin and Bangoura onstage for a talkback. The cinema, more like an auditorium now, was bubbling with curiosity and newfound ambition.

Someone in the audience asked how long it had taken to make the film. “Six years is the short answer,” said Matchan. The crowd gasped. “Yeah, I know!” she replied.

Others asked about travel, about expenses, about sources of inspiration. They asked Bangoura where his brothers were, and they asked Saladin about when he started doing circus. In turn, the acrobats and filmmakers asked the students what lessons they had taken from the film.

“Stay determined no matter what the problem is,” said one.

“Never give up,” answered another.

Bangoura nodded in agreement, and expressed again how lucky he felt to be there—and how lucky the students were to have the opportunity to be there too. He asked them about what activities they enjoyed, and whether they could practice them in places like at school.

“In Africa we don’t have that chance,” he said. “So take that chance and do something with it.”

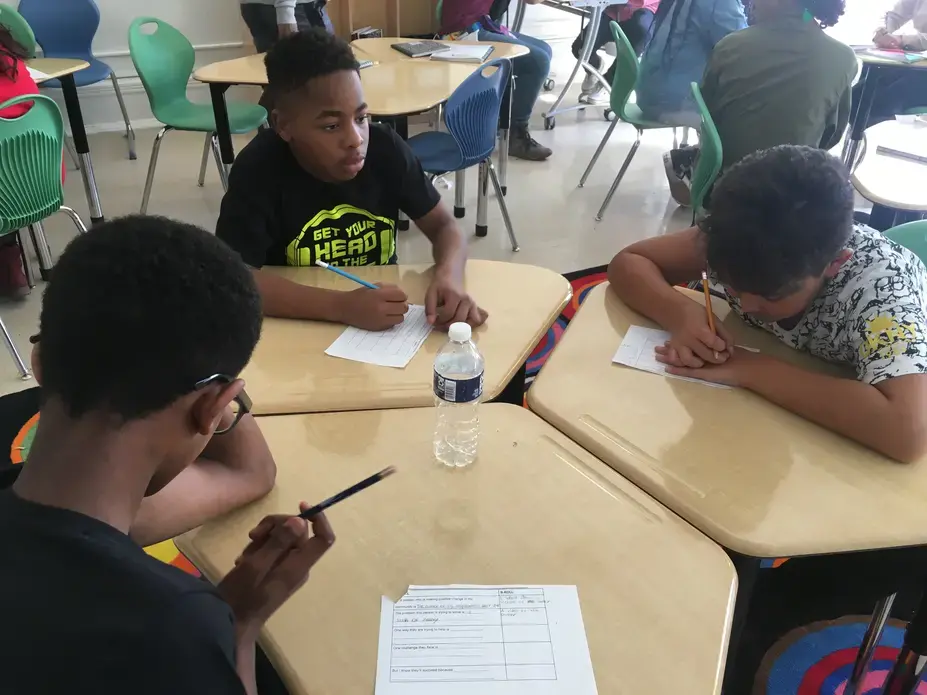

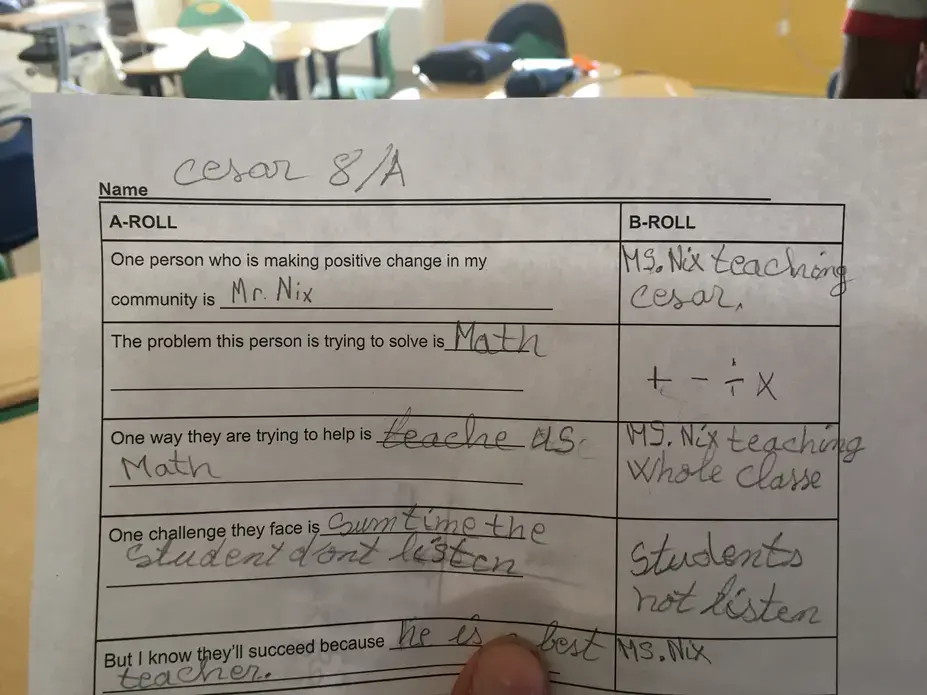

At the end of the week, Matchan and Gray visited the students from Eliot-Hine and Creative Minds again, but this time it was for interactive workshop in their classrooms. Once more, Pulitzer Center education team members facilitated in-class sessions to review what the students had learned the previous week. What was A-roll? What was B-roll? The students practiced identifying different kinds of shots with images from "Circus Without Borders."

Now that they had learned a thing or two about filmmaking, Matchan and Gray explained that images can serve several goals. Sometimes, a shot could be an action shot and archival footage. Sometimes, a shot with a subject in it could be more of an exposition shot than an action shot, if it served to establish a sense of place. They asked students, "How could you use images to tell stories about people who are making important changes in your communities?"

Thus inspired, students went on to create their scripts for documentaries they would want to make about people in their communities who were making positive contributions. They brainstormed subjects from their homes and their schools, paired A-roll with B-roll, and envisioned stories that they could tell for themselves.