For their project Built to Last, a Pulitzer Prize-winning investigation into China’s re-education camps in Xinjiang, journalist Megha Rajagopalan, architect Alison Killing, and programmer Christo Buschek drew from publicly available satellite images and dozens of interviews with former detainees. The result is a comprehensive account of the scale of the internment camp system in Xinjiang as well as the details of what life is like inside it.

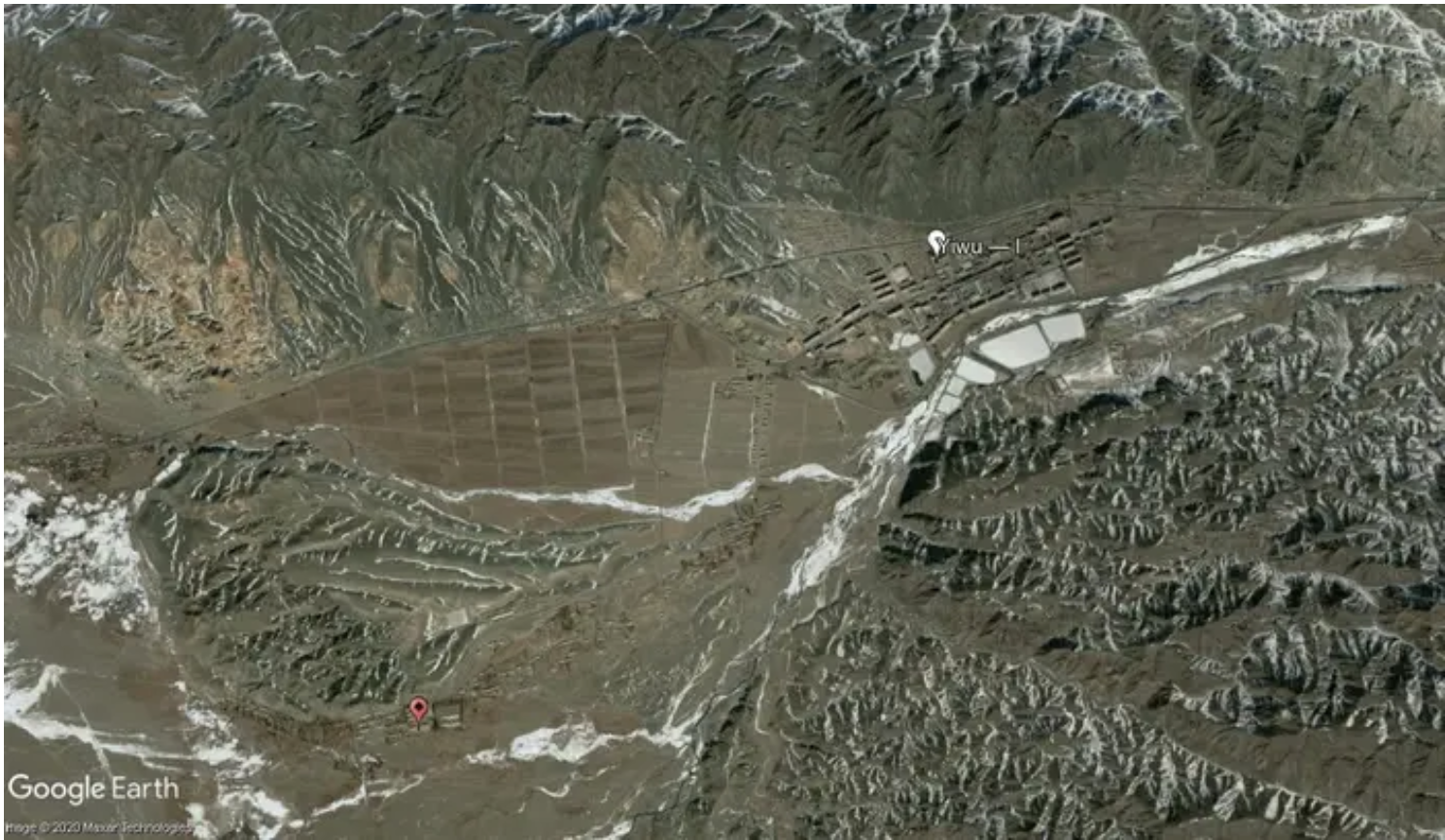

The Pulitzer Center-supported investigation, published by BuzzFeed News, identified more than 260 structures that were built after 2017 and that bear the hallmarks of fortified detention compounds. Built to Last reveals a sprawling system established to detain and incarcerate hundreds of thousands of Uighurs, Kazakhs, and other Muslim minorities.

"What we loved about this project is the ingenuity of the reporting approach—marrying satellite data analysis, architectural renderings and traditional shoe-leather reporting to show the true scale of a cultural genocide the Chinese government claims doesn't exist," said the Pulitzer Center's executive editor, Marina Walker Guevara. "It's a great example of how interdisciplinary work and data journalism can help circumvent censorship."

Pulitzer Center intern Abigail Gipson spoke with Rajagopalan and Killing about how they collaborated to tell this story.

AG: Could you tell me a little bit about your background and how it affected how you approached this project?

AK: I came to work on this because I met Megha. We met at a workshop in the summer of 2018. She had recently left China—her visa was not renewed because she'd been doing a series of really good, really effective investigations on what was happening in Xinjiang. And so she ended up having to leave, but wanted to keep working on that story. One of the things that she was interested in doing was using satellite imagery to try and find the camps.

I’ve done quite a lot of satellite imagery analysis and mapping work, so we had complimentary skills for going out and doing that. My background is as an architect, I've also done some work in urban planning. Alongside my architecture degree, I did a degree in development and humanitarianism. So I ended up doing quite a lot of human rights law as part of that.

And so over that summer, we kept in touch. I would spend a couple of hours having a think about different ways we could approach this investigation using satellite imagery. It was after a couple of months that I landed on the masked tiles in Baidu [Editor's Note: Baidu is a leading search engine in China that offers satellite imagery mapping services] .

I had seen a story in Wired about Baidu’s Total View, where industrial buildings had been clumsily photo-shopped out of the landscape. And it just seemed like if Baidu was masking that sort of building, the internment camps would possibly be edited out in a way that was similarly easy to recognize. And so that's what we went looking for.

We had a list of camps which had already been visited by journalists and confirmed. So we could be very sure that those places were camps. And so we went to look at those on Baidu. I was looking at the satellite view, and as I was zooming in, suddenly a blank tile appeared where the camp should be.

And it kind of just looks like the thing hasn't loaded properly, and you zoom in further. Baidu didn’t have very detailed satellite imagery at the time, and so you would just get the standard gray map with lines for the roads. But then zooming out again and zooming back in, the same thing happened. Which it shouldn't do because there should be a cache in the browser. So it looked like something a bit strange was going on.

I went and looked at a number of other sites where we knew there were camps, and found the same thing happening there. Once we realized that we were able to replicate this process with the masked tile and that it was happening at all of the locations that we knew to be camps, we realized that we had a technique that we could use to try and find the rest of the network.

MR: My background is much more a traditional journalism background. I have a journalism undergrad degree and I studied abroad in Hong Kong when I was in college. After I graduated, I started as a trainee at Reuters in their Beijing bureau and then ended up being a political correspondent for Reuters for four years and then moved to BuzzFeed News in late summer of 2016. At that time BuzzFeed wanted to open a China bureau. They were interested in doing the longer, in-depth type of reporting that BuzzFeed is known for from their investigations team.

I had it in my mind that I wanted to do some more reporting on the Xinjiang situation. This was before all of the stuff that we wrote about even started.

In 2017, we started to hear that things were getting a lot worse in Xinjiang. It had always been repressive there. I had covered lots of the developments there for Reuters, ranging from knife and bomb attacks that the government has blamed on Uighur military groups coming from abroad, as well as some of the issues around migration and human rights.

I had a colleague who was working for a different media outlet who had gone with a photographer to do a number of stories. And then, on the last day their driver told him, “This has been great, but, I'm not sure if I'll see you again, because they've told me that I have to go to re-education” and he's like, “What is re-education?”

We assumed that it was some kind of camp, some kind of extrajudicial detention facility.

After that, I went to Turkey to meet with some exiles. I went back [to Xinjiang] to try to find some of the places that these exiles talked about, including one of the detention centers in the city of Kashgar. I just went on foot to try to find it. So we ended up publishing a piece that was the first in a series of coverage that BuzzFeed has done on the Xinjiang issue by myself and other journalists.

It did result in me losing my visa, unfortunately. I think that's been interpreted to be the case, although the Chinese government has never said one way or another.

I was sort of in visa limbo when I met Alison. I was really excited to meet Alison because I had never met somebody who was doing the kind of work that she was doing on human rights issues. Especially as a journalist, we really should be working with more people with skill sets like this—you could approach the story in a completely different way.

I had been sort of in the woods with this for a couple of years, and I had this whole process for how I was reporting these stories. I would go and talk to exiles. Sometimes I would look at company documents or government documents, but by and large, these were all very traditional journalistic investigative channels.

Alison was looking at this, and thinking from her perspective, how can we find all of these camps? How can we uncover information about this crisis that has to do with space and where things are located? And then what does that tell us about what the government is prioritizing in terms of where they build camps? What does it tell us about how many people that the system can hold? All sorts of questions like that, that I didn't think were even possible to answer through traditional journalistic methods.

We approach a problem from two different perspectives, and it turned out to be pretty complimentary. You can see that in the series because a lot of the big revelations came out of the analysis that we did using maps.

I think the strength of it in showing the real-world harm that these policies are doing comes from marrying the information, from maps and from other forms of analysis, to people who were really there and stayed in those places. So it’s both the human impact and trying to measure the sheer scale of the problem.

AG: Has approaching this project in this way given you any new perspectives on the situation in Xinjiang or how other issues could be investigated?

MR: For me, it completely changed my view of the whole policy in Xinjiang. I didn't expect to find some of the stuff that we found. When we started looking at this, it was thought that there were like 1,200 camps in the whole region. I was really shocked when we started to see how much fewer they were and how much bigger some of them were. And how high the security was.

I think that that's part of why the series is called Built to Last. It's to make a point that this is an infrastructure that doesn't appear to be about a temporary drive to detain Muslim minorities, but appears to have the ability to become a much more permanent system. That was really surprising to me and really scary as well.

AK: Using satellite imagery has allowed two things that were very, very difficult in Xinjiang. One of them was access. Traveling around the region and investigating things like this just wasn't really possible.

There's a lot of stories describing the obstacles that journalists have faced while trying to work in Xinjiang; repeatedly being detained, the police staging car crashes to stop people driving down certain roads to visit a camp, things like that. And so that access issue is a huge one that we were able to overcome using satellite imagery.

It's also an information source that the Chinese government can't control. So that meant that we had this window into what was happening in the region that we otherwise wouldn't.

The other thing is the scale of the region. I think Xinjiang is like the size of Alaska. So even to just travel around and try and find these places would be an impossible task. Having worked through this and having found all of these camps, we've been able to show the scale of the program.

But to only be showing the scale of this and to only be showing the data, even as powerful as that is, it's very dry. As Megha said, you really need those human stories to explain exactly why this is important.

AG: What were some of the challenges to not being able to report from Xinjiang? How did you get those personal stories without actually going to the region?

MR: It's suboptimal. The optimal thing would be if you could go to the region and interview people. But it is a place that's very hard for journalists to work because you will be followed by police officers if you have a journalist visa in your passport. So it makes it very tough. The other factor that makes it tough is, from an ethical standpoint, you have to always worry that when you talk to people, there may be some kind of blowback on them.

So we relied really heavily on the accounts of exiles, and we're super grateful to them for having the incredible courage that it takes to step forward for a news story. For this series, most of the exiles were in Kazakhstan.

There is still a risk to them, as many of those people still have family in Xinjiang. But there are quite a few who have a stable, permanent residential status in Kazakhstan and who will speak to journalists.

AG: Since you've been covering this issue for a while, have people been more or less willing over time to come forward with these stories? Have you noticed any changes?

MR: I think definitely more. The reason is that when this was starting, nobody knew what it was. Even the people in the region didn't really know what it was. So, people were deeply afraid that if they said things publicly in any way, there would be repercussions for their families, even if they were abroad, and that somebody could be sent to a camp as a result of something they said.

And as the government's campaign progressed, it became clear that a lot of people were going to be sent to these camps regardless. People would be sent to a camp for having a relative who lives abroad, let alone if that relative becomes a named person in the media.

In short, things got worse to the point that people felt they had no alternative. They felt either they personally had nothing to lose anymore, or they felt that it was so bad that somebody had to speak out and they had to do it because nobody might if they didn't.

I know so many people who know about terrible human rights atrocities that have happened to their families, and are desperate to speak out about it, but then they choose not to, to avoid the blowback.

So that's something that I wish there was a way to make people understand, which is that the people who come forward to speak out in Xinjiang coverage is just like the tip of the iceberg.

AG: Alison, I'm wondering what the process was like of creating these models of the camps. Do you hear the first-person accounts of what it was like inside, and then use that to inform your work?

AK: In the Mongolküre story, that's what we did. So I made a first pass at what I thought the interior of these buildings looked like based on satellite images and based on what is essentially standard construction knowledge. We have a regular structural grid, so there’s probably a regular pattern of rooms.

We could work out based on roof patterns and what I know about fire regulations, where you need staircases to be able to get out. Once we had that basic model, it brought up more questions that we could then ask the former detainees.

We also had a number of leaked videos that were made by construction workers in a different camp slightly farther north. That was also really useful to work from; they have similar features. It gave us ideas of what we should be asking about like, is the bathroom inside the cell or is it down the corridor or, how many beds were inside there? Which was a really difficult question to get to the bottom of actually, because the number of people that were being held would change. And based on the occupancy of a single room, we could then start to guess at what the occupancy of the entire building was.

The people who Megha interviewed were able to tell her things like, yeah, it's mostly cells on the floor, apart from one classroom and then on the ground floor, there's a canteen.

We could then start to work in quite a lot of detail. And we worked back and forth from that, asking people how many windows there were in the cells. And then we could count windows and be like, OK, so there's 14 windows along the facade. That probably means like 14 cells, 13 give or take. Similarly with the classroom, we went back and forth with how many windows were in the classroom, trying to work out how big that room was as well.

MR: Like Alison says, I think a big part of this project and the impact of this project is just the scale. I think nobody had really tried to do that before. It was really interesting to go back and forth to the satellite images and the ex-detainees because so many of them had similar descriptions of what camps looked like, and these are camps in different parts of the country. The windows thing is a really good example. Almost everybody that we talked to said that they had a specific kind of barricade along the window.

This is very useful as a journalist because it's very hard to fact-check these accounts. Now if somebody is talking about a different kind of barrier in the windows, I start to think, OK, this is a little bit different, so why might this be different?

It made the interviewing really interesting because I would ask people to draw what they remembered of what it looked like. And then in some cases I would sit with them with a computer with Google Earth open and they would point to different things and say, “This is this, this is that.”

I was initially worried because I don't want to cause any additional trauma to somebody by bringing them back to a place they may not want to remember. When that might have been the case, of course we stopped. But in other cases, there were a few people that really appreciated being able to contextualize this experience and be able to explain and articulate what had happened to them in a way that was so clear for somebody else to understand.

I'm glad that we went to them with that in mind because it helps give that person an additional layer of proof and meaning to their experience that they wouldn't necessarily get in a traditionally reported story, which is mostly focused on people's recounting of their individual experiences.

AG: Why was it important to show what the space physically looks like?

AK: I think it opens up a lot of understanding about what that place is like when people can really see, like, “Wow, these rooms are really small. There's 10 people squashed in a space that's a little bit bigger than a typical garage.”

There are so many aspects of life in the camp that producing this model opened up. It helped us think through just how small your world is. You go from this one cell where you're spending 23 hours a day to just the classroom next door. You may not move more than 10 or 15 meters for weeks. People wouldn't have any access to fresh air. The total lack of stimulation in these places must have been really, really difficult.

MR: From the kind of interviewing standpoint, it's been very interesting because for ex-detainees, this is an experience that takes up anywhere from several months to more than a year, and so if you ask somebody what they did every day, they'll have one answer for you. But you won't get to the really mundane stuff that they have sort of internalized as normal. But once you start talking about space, you can get to those answers.

Alison gave a couple of really good examples, but another one is the cameras. The first time somebody told me there was a security camera in the toilet, I was like, “Oh really?” And then they were like, “Of course, obviously, there were cameras everywhere. There was no place that we could go where there wasn't a camera.”

Doesn't that tell you something pretty significant about how surveillance works in the camps and how privacy is just non-existent to people?

And then like Alison said, just the extreme confinement of the spaces. You can interview a lot of people who tell you it was really small, and it felt so cramped, but people are really bad at estimating the size of places. They can tell you how many people were there, but they may not be able to tell you in meters how wide it was. But then once you start talking about, “Oh, how many paces could you take?” And then you add in the satellite image, and you could measure the width of rooms.

Then it starts to become just a lot more visceral, more visually compelling for the reader. So I think those are all the reasons that it's valuable to use this type of approach.