For millennia Indigenous communities have relied on the far north's caribou herds for sustenance. But as the herds dwindle, the future becomes difficult to predict.

Clyde Morry is chasing the herd hard. He jams the throttle down, spitting up a fine curtain of white crystals. I follow and can’t keep up. I turn my own machine this way, that way, flailing over the same frozen ground, but I’m just not that good, and not as hungry as Morry is for the kill, the pounds of savory meat—or the warmth that will flow up into his hands as he butchers the big caribou. For some reason, even though it’s 25 degrees, even though the April wind whipping through this mountain pass pushes the chill down further, Morry never seems to be wearing gloves.

“Just slows me down,” he says later.

Everything about Morry is quick—his temper, his basketball game, his work with a skinning knife. And this is no elegant chase: It’s hot pursuit. Morry kicks through a few more turns, then skids to a stop, unslings his rifle, and takes aim. A shot like a popped balloon, small and hollow against the huge mountains, the empty sky. A hundred yards away a cow goes down. The rest of the herd, 10 or 15 mothers and their calves, keep running but not too far, as though they know the worst is over.

As a nonprofit journalism organization, we depend on your support to fund more than 170 reporting projects every year on critical global and local issues. Donate any amount today to become a Pulitzer Center Champion and receive exclusive benefits!

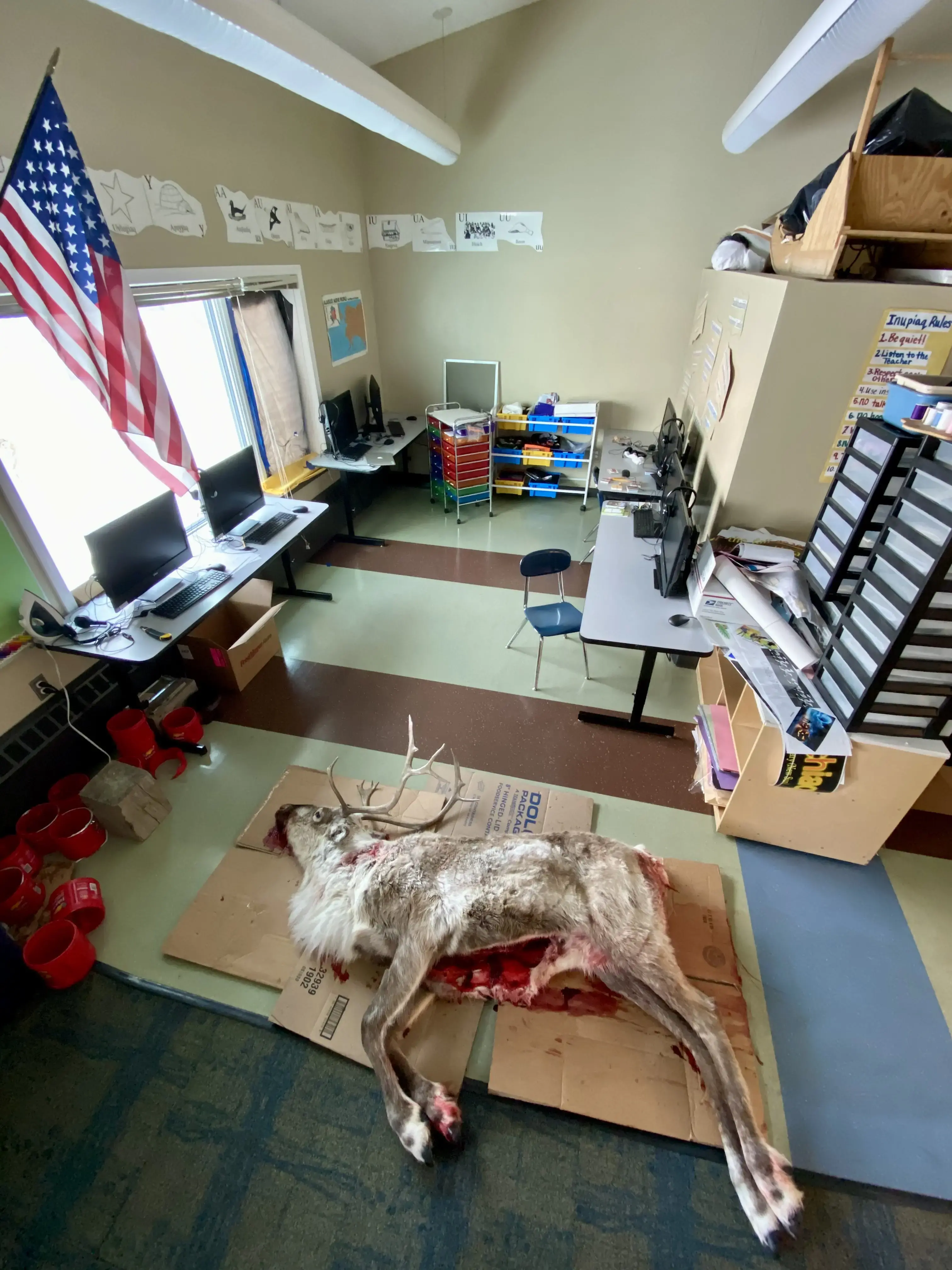

Morry and I drive up to the cow and see his shot has been clean. He slips out a knife from his black coveralls, bends over the body, gets to work. First, he severs her head. His people, the Nunamiut of Anaktuvuk Pass, Alaska, believe this and what follows are the most important steps. He carries the head a little distance away, gently, as though he were carrying a favorite cat, and places it just as gently in the snow, upside down. The cow’s inua, her soul, may now escape and fly to the spirit world. There, a guardian spirit will comfort the cow’s soul and then send her to Earth again in a new body.

This is the cycle of respect and return and renewal. Morry is 37, and it’s what he knows, what he was taught, and what he teaches his children. After the head is set, Morry begins butchering. Quick sharp strokes. Slick red hands. When his fingers get cold, he shakes them and blows on them and places them against the body to soak up some of its fading heat. When the meat is finally stacked onto a sled, he says, “Maybe I’ll put on some gloves for the drive home.”

He does, and drives back to Anaktuvuk Pass at a much safer speed. This is not to say he drives slowly—he is mindful not to let the meat freeze. But this time I manage to keep up. Even, once, to pass him. As I do, I notice he’s grinning. Morry has no job but this; he wants no job but this. Hunting is how he provides for his big extended family. And tonight at home there will be plenty of food and plenty of people gathering to eat it.

Morry’s father will ask me, “Did you see him turn the head over?”

“Yes,” I’ll say.

The elder will nod. “Don’t forget.”

THE CARIBOU COW CLYDE MORRY KILLED belonged to the Western Arctic herd, sometimes simply called the Western. At the time, in early 2021, the Western was one of Alaska’s largest groups of caribou. In the 1990s, when Morry was learning to hunt, the Western was on its way to a high of nearly 500,000 animals, and they roamed a territory about the size of California. Many of them walked right past Morry’s house twice each year during their spring and autumn migrations, providing his community with a steady source of food and spiritual well-being in a roadless and extremely remote part of northern Alaska.

But by 2021, the Western’s numbers had dropped by more than half. Some years, Morry and other hunters told me, very few caribou trickled through Anaktuvuk Pass. In other years, they arrived weeks late or didn’t come at all. None of this was necessarily unusual—caribou herds have been known to fluctuate in size over time, and they are wild beings, heeding their own instincts, schedules, and motivations. Placed into a larger context, though, the decline is deeply unsettling because the Western is not alone.

Migratory tundra caribou can be called many things: barren-ground caribou or eastern migratory caribou in Canada, while in Alaska “caribou” alone will usually do. In Russia and Norway, nearly identical animals are called wild reindeer. All of these live in extreme northern habitats between the tree line and the remote reaches of the Arctic tundra, and they make long migrations. No matter where you look or what you call them, they have been fading away for decades right before our eyes.

Between the late 1990s and 2018 these animals declined by some 56 percent, from about five million to two million. After 2018, data on Russian reindeer (as well as collaboration with Russian scientists) were harder to come by, but in North America the fall continued. Of about 13 major herds in Canada and Alaska, most have suffered steady losses, and at least one, called the Bathurst, has disintegrated to the point where it may disappear completely within a couple of years.

There’s no consensus on what’s behind this great vanishing. No disease has been pinpointed, no individual culprit gets the blame. No remedies or policies seem able to stop or even slow it. To anyone who lives south of the Arctic Circle the problem can seem abstract—another distant note of sadness in an era heavy with extinctions. But this is not how it appears in the far north.

In small communities scattered along the tree line or set in the open tundra, towns such as Anaktuvuk Pass that are often isolated, often Indigenous, where imported food and gas can be astronomically expensive and hunting caribou is often the cheapest and fastest and certainly the most satisfying way to provide for a family, the decline brings a peculiar dread. An Inupiat elder in a coastal town told me it was like feeling the symptoms of a cold coming on. The cold arrives, and it lingers. You don’t get over it. Then it worsens, until you become gaunt and haunted, until you’re afraid it isn’t a cold at all but something deeper. Something that’s shot through your whole system.

This is how the caribou problem feels to many Native people in the north, including the Nunamiut. Their name means “people of the land,” but anyone will tell you that they are, most of all, a caribou people. They are also sometimes called America’s last nomads, because only in about 1950 did the Nunamiut give up a mobile life, a life spent hunting and following caribou. They chose to settle in Anaktuvuk Pass exactly because the herd poured through it like a river. The name Anaktuvuk means “the place of many caribou droppings.”

One night after I’d gone out hunting with Clyde Morry, his father, Mark, made a quiet comment about the choice his people had made. Mark Morry was a veteran of the Vietnam War. Thick gray hair, thick old glasses. He sat in a recliner by a window in the house he had built, watching his family eat caribou that Clyde had brought home.

“It was a big gamble for them to settle down like that,” Mark said of his own father and mother and uncles and aunts, the generation who gave up nomadism. “They figured the caribou would always be here.”

WHEN WILDLIFE BIOLOGIST HEATHER JOHNSON arrived in Alaska several years ago, she was surprised to discover how mysterious caribou still were. Like other northern creatures—polar bears, say, or narwhals—caribou live what writer Barry Lopez once called obscure lives. They can be hard to find. Expensive to study. They spook easily. Even what they eat has been, at times, difficult to pin down. This is a major reason their decline is so puzzling.

“I didn’t think there was a terrestrial large mammal left in North America that we didn’t know much about,” said Johnson, who works for the U.S. Geological Survey. “I thought, how can we possibly know so little about these animals? But then an older colleague said, ‘Heather, you’ve got to flip that around: You should be impressed that we know even as much as we do.’ ”

Consider, for example, that only recently did researchers confirm that caribou are among the planet’s greatest wanderers. Using data from satellite tracking collars, a team led by Kyle Joly, a wildlife biologist with the National Park Service, showed in 2019 that the animals can travel more than 800 miles each year—in point-to-point, straight-line terms—on their migratory circuit. That’s farther than all other terrestrial mammals.

During these epic journeys caribou may navigate between dark spruce forests and sun-bleached tundra, or from bleak mountainsides to wind-blasted coastal plains. They’ve even been known to walk into the sea. They also face an array of natural hazards—wolves, bears, ice-choked rivers, galactic swarms of mosquitoes, and life-draining parasitic flies—as well as an ever increasing set of human-made obstacles: oil fields, roads, and mines.

Climate change, too, is rapidly transforming their habitat. Rising temperatures across the Arctic now routinely disrupt familiar weather patterns. Where snowstorms were once the signature weather event of an Arctic winter, freezing rain is becoming more common, locking caribou forage away under impenetrable lids of ice. Summers are also growing longer, which isn’t necessarily a good thing: Warmer temperatures bring new plants and animals, more parasites, and even wildfires to the tundra.

All these forces affect caribou in ways we’ve only begun to unravel. What it means is that if you’re a scientist, a hunter, a conservationist, or anyone who comes looking for a reason for the vanishing, you’ll suddenly find yourself staring into a problem as big as the landscape itself.

“I THINK BY NOW IF THERE WAS JUST ONE THING, we’d know it,” said Jan Adamczewski, a Canadian biologist. “But when you draw up a list of all the things that might be affecting caribou, it can be a very long list. And when you draw up a list of things you can do about it, it’s usually a very short list.”

Adamczewski works for the government of the Northwest Territories, which is home for at least part of the year to seven migratory tundra caribou herds. This includes the Bathurst—the one that has come to represent a kind of worst-case wildlife scenario. In 1986 the herd numbered 472,000 animals. From there it began a gradual decline that eventually tumbled toward collapse. By 2021, the herd had dropped 99 percent.

The fall was extraordinary, and when I asked Adamczewski what might be behind it, he sighed. He was used to the question—often posed by people who’d already arrived at their own conclusions. Adamczewski told me that many people he spoke to believe climate change had something to do with the herd’s decline. But the term was vague, the effects hard to parse.

It was a lot easier, Adamczewski said, to zero in on smaller, more discrete suspects. Wolves were a popular villain. Other people believed hunters were killing too many animals. And within the Indigenous communities that make up nearly half the territory’s population—and that stand to be most affected by caribou loss—mining was often seen as the greatest threat to the herds, Adamczewski said.

Around the time the Bathurst seemed healthiest, a handful of mines opened in the Northwest Territories, including Colomac, a gold mine, and Diavik and Ekati, both diamond mines. All of them sprawled across the home range of the Bathurst, and Lupin, an older gold mine, lay due south of their calving grounds in Nunavut.

“Everyone around here knows that the Bathurst were at their peak [then]. And then the mines came and roads were built, and the caribou started to decline.” For many people, Adamczewski said, it was no coincidence.

Several studies have shown that industrial development disrupts caribou behavior. The animals often seem to perceive roads and pipelines in particular as obstacles blocking their migratory paths and feeding patterns. They also tend to avoid mining camps and oil fields, which can leak chemical odors and tailings, shake the earth with drilling equipment and truck traffic, and fill the air with the racket of planes and helicopters.

While mining in the Northwest Territories will almost certainly carry on no matter what happens to the Bathurst (the territory is heavily dependent on the industry, which provides thousands of jobs and millions of dollars in revenue), Adamczewski said the territory and several First Nations had attempted other approaches to halt the Bathurst’s hemorrhaging. In 2015, he said, the territory established a controversial hunting ban, which was supported by local Indigenous communities. The territory has also tried to reduce wolf numbers by, among other things, shooting them from aircraft. Still the herd shrank.

ONE OF THE MOST HAUNTING CONSEQUENCES of decline, for the Bathurst itself, appears to be an increasing loss of identity. In caribou biology, the term “herd” usually refers to a group of animals that all return to the same place to give birth—the same calving grounds. Mothers teach their young how to navigate there, show them different feeding spots along the way. They also share alternative routes, detours that might be useful depending on what the weather or the wolves or the human hunters are doing.

I’ve long thought these migrations resembled pilgrimages. The education of younger animals (delivered mostly by older females) is connected to what scientists often call the herd’s collective memory: its unique and enduring way of knowing the landscape. Some have even begun to call such practices culture. These cultures are cohesive enough that the animals tend to stick with their own and remain loyal to their calving grounds.

But Adamczewski said that in recent winters the Bathurst had been mixing with another, much larger, herd called the Beverly. Maybe the Bathurst caribou were seeking safety in the Beverly’s numbers. Maybe they would fold into the larger herd. It was still possible for them to recover; other herds had come close to disappearing and scraped by. But the Bathurst’s singular culture—its way of being, as an Indigenous friend had put it to me—was at risk of blinking out.

“If we lose one of these herds, there’s a lot in terms of behavioral memory that we also lose,” Adamczewski told me. “When caribou don’t visit their traditional calving grounds, they don’t seem to live as long.”

Caribou live obscure lives. They can be hard to find. Expensive to study. They spook easily.

Seen against other changes unfolding in the far north—greening tundra, melting sea ice, burning forests—the unraveling of the Bathurst appeared like a symptom of dementia, the landscape losing another piece of its identity. Would the Bathurst’s condition spread? Was it irreversible? Was there a cure? No one knew.

Adamczewski said he found hope in small details: signs of growth in one herd, say, or a slowing rate of decline in another. Even holding on to a broader sense of time itself helped.

Caribou herds seem to follow cycles, he said, phases of boom-and-bust during which they peak and then contract. Across Alaska and Canada, many herds, including the Western, bottomed out in the 1970s and then began to climb into the ’90s and early 2000s. Indigenous oral histories record even earlier eras of plenty and of dearth.

If cycles do exist, their causes are unknown and appear to operate on decades-long intervals. The idea is attractive because it suggests caribou herds naturally bounce back. But it can also be misleading, many researchers warned me, because in a rapidly changing, warming world even the most durable creatures may not have enough time to recover.

“There are times when we do lose herds on the landscape, and there are times when new herds will be forming as well,” Adamczewski told me. “Herds are not immortal. They’re not fixed forever in time and space.”

ON AN OVERCAST DAY IN AUGUST 2021 I stood on a green tundra plain in an isolated corner of Nunavut, looking over dozens of caribou trails. They were deep and narrow, and they scored the earth in every direction, like rows of corn, like rays of light in a child’s drawing of the sun. You could pick any of them and walk it to the horizon. Maybe all the way back to the city of Yellowknife, 250 miles to the south.

I chose a trail and followed, clumsily, slotting one boot in front of the other. Beside me a stout, athletic man named Roy Judas did the same. He wore woodland camouflage, though the nearest tree was more than a day’s walk away. And he carried an old lever-action Winchester rifle, in case of bears, or “big men,” as his people, the Tlicho, sometimes call them—a term of respect. On that day, though, the big men were absent, off hunting or munching cloudberries somewhere else.

Everywhere we turned, the tundra appeared empty. We were near the calving grounds of the Bathurst; the old trails were probably theirs. But the caribou were absent too.

While I walked, I tried to imagine the volume of animals required to shape the landscape this way—to impress their passage so firmly. Tens of thousands of caribou. Decades of migrations. The earth thrumming under their spadelike hooves.

“Used to be a highway for them,” Judas said. “All gone now.”

Like Clyde Morry in Anaktuvuk Pass, Judas had grown up hunting caribou in the forests near his home in Wekweeti. His mental maps of the landscape, as well as his people’s language and culture, were flecked with caribou-related landmarks, stories, vocabulary. Skins from Bathurst caribou had once been their most valued resource. In the form of tents, equipment, and clothing, they made human life possible along the cold frontier where the great northern forests faded into open Arctic tundra. Some Tlicho told me they could even taste the difference between Bathurst caribou and animals from other herds.

Judas could no longer hunt the Bathurst, of course: The Tlicho, a First Nation, had abided by the territorial hunting ban. But this decision, he and others told me, had not been easy. By that time the Tlicho (sounds similar to CLEE-cho) had already suffered from decades of colonial practices, including language and cultural loss. The collapse of the Bathurst only deepened a sense of existential crisis. If the Tlicho couldn’t hunt the Bathurst, if they couldn’t maintain traditions and ancient bonds with the animals, who would they themselves become?

The Tlicho were still wrestling with the question when I joined Judas and several other Tlicho citizens on the shore of Koketi, also called Contwoyto Lake. One of the nation’s answers had been to create a program called Ekwo Naxoehdee Ke, which means, roughly, “following in the trails of the caribou.” (It’s also known as Boots on the Ground.) For part of each year Judas worked for the program, leading groups of Tlicho citizens to Koketi, where they spent weeks camping, hiking, and searching for remnants of the herd.

“When we find them, we take notes,” Judas said. “We watch them, we follow them. We try to get close and figure out what they’re up to.”

The observers counted caribou and recorded other details, including how they looked, where they were traveling, what they were eating, and who was eating them. At the end of every summer, the results were returned to the Tlicho government, which used them to guide management decisions for the Bathurst.

“The main reason for creating that program was for our own Tlicho people to be the eyes and ears of what’s happening out there with the caribou,” said Tammy Steinwand-Deschambeault, director of the department of culture and lands protection for the Tlicho government. “The elders didn’t want to rely on the territorial government or anybody else to say, ‘This is what’s happening; this is what we’re seeing.’ The elders said, ‘We need to see for ourselves. So let’s get out there.’ ”

Steinwand-Deschambeault told me the Boots program also had secondary goals: to expose younger Tlicho to language and hunting skills (if not hunting itself) and to keep contact with the Bathurst.

“If we’re not on the land, the caribou think that they’re not needed,” she said, and they might decide to go away. “So we need to go back to being out on the land more, you know—attend to these kinds of relationships. We have to do our part.”

DURING THE TIME I SPENT WITH JUDAS and his crew, we saw many animals. Enormous bears, trout as long as my leg, eagles, cranes, muskoxen, and a young white wolf that walked through our camp as though she owned the place.

We also passed through layers of deep human residence. Century-old campsites, hunting blinds built of stacked boulders that dated back to an era of arrows and spears. Often, when we paused to rest, we found our feet surrounded by “lithic scatter”—shards of stone left by hunters who’d long ago sat in the same spots, knapping tools from flint or quartz.

But there were very few Bathurst caribou. At the time, only about 6,000 animals were believed to remain. That number seemed large, at first. With a little effort, I thought, we couldn’t help but find the herd. Judas gently corrected me. It would be easy, he said, for so few animals to disappear into the belly of the tundra. As the days dragged on without many sightings, I began to grasp the scale of the problem.

I live in New York City. The closest wild migratory tundra caribou roam some 1,000 miles away in Ontario. Even for me, after years spent working on this piece, interviewing dozens of people and camping many nights in caribou country, the animals are usually out of sight, out of mind. Less like a fellow being and more a distant idea, a shadow drifting over the map. Multiply this conceptual distance across most of our lives, and you see why their fate doesn’t summon a sense of alarm in the capitals of Ottawa or Washington.

For Roy Judas the response was clear, and it was personal. In summer, he counted caribou on the tundra. In winter, when the Bathurst migrated back into the trees near his hometown, he worked for the territorial government helping to enforce the no-hunting rule. It was his way of respecting the animals. Of tending to the old relationship. And for a while it made him unpopular.

Back in 2015, when the ban took effect, not everyone had supported it. Some Tlicho resented the notion that outsiders were trying to control their herd. They wanted to keep hunting, as they always had, and occasionally Judas’s job forced him into uncomfortable conflict with neighbors. Once, he’d even caught an old friend hunting.

Late one evening on the tundra, as we tripped through caribou trails, Judas told me that people seemed finally to be coming around to his way of seeing things.

“What way is that?” I asked.

He swatted a mosquito, hefted his rifle to the other shoulder. “I want there to be caribou in the future,” he said.

HEAD WEST FROM THE LAND OF THE BATHURST, across the Northwest Territories and into the Yukon, toward Alaska, and you will find the outlier in this story. Here, touching the coast of the Beaufort Sea, straddling the international border, and reaching into the lands of the Inupiat and Gwich’in, lies the range of the Porcupine herd.

When I began this project, nearly every researcher I spoke with was quick to point me toward them. The Porcupine, they said, seemed to be bucking the continental trend. And it wasn’t that the herd had simply failed to collapse: Their numbers had recently increased.

Between 2013 and 2017, when the Bathurst were steadily shrinking and the Western soon would be, the Porcupine grew by about 21,000 animals to reach 218,000. This despite climate change, despite wolves. Despite everything.

For many scientists and hunters, this felt like hope. It wasn’t clear why the Porcupine were thriving while other herds declined all around them; as with everything caribou, the answer was likely hidden in the intricate weave of climate, biology, and landscape. But briefly it looked as though the Porcupine might hold a secret, some clue that could help illuminate, or maybe slow, the vanishing.

It wasn’t clear why the Porcupine herd was thriving while other herds declined.

Lean on an outlier, though, and it often begins to shift. Heather Johnson, the USGS researcher, recently cautioned me not to make too much of the Porcupine’s numbers. The herd hadn’t been accurately counted for six years, she said, and in the meantime, hunters have observed worrisome trends in body condition: The caribou are increasingly in poor shape, packing less of the crucial fat that helps them survive brutal Arctic winters. “The idea that they’re not declining is kind of out of date,” Johnson said. “We really don’t know.”

Around the time this article went to press, in fall 2023, some people I spoke with were anticipating the release of new caribou surveys, which are usually done over the summer. The Western and Porcupine were both due for fresh counts, and an increase in either could boost the mood, even affect hunting regulations. On the other hand, bad numbers would only deepen the gloom.

Kyle Joly, the National Park Service biologist, told me it had already been a tough year for the Western. He’d spent part of July in northern Alaska recovering satellite tracking collars from caribou that had died during a brutal winter that saw deep, wet snow—cement-like stuff that’s hard for caribou to travel through. In September brighter news unfolded on the state’s oil-rich North Slope where the Department of the Interior canceled all petroleum leases in the immense Arctic National Wildlife Refuge, home to the Porcupine’s calving grounds.

The news was celebrated among the Gwich’in, for whom the area around the calving grounds is holy, “the sacred place where life begins.” But human hunger for oil still looms over the Porcupine’s future. While there’s no drilling in the refuge now, there’s also no guarantee a new administration, or a new Congress, won’t push for it. Local and national politicians have already tried and failed dozens of times.

“I think it’s been hard for us to quantify how much has been changing for caribou,” Johnson told me. But “if there’s one thing they don’t like, it’s industrial development. They are just really sensitive to development. It’s been shown so many times.”

In a mystery the size of a continent, she said, this may be the best lead we have.

CARIBOU ARE CREATURES OF HABIT, and their habits seem synced to an older and colder world that no longer exists. The question in our time is how quickly they will or won’t adapt. Late one October I stood alone on the shore of the Kobuk River in western Alaska, watching a young male try to swim the black water. He struggled. Large rafts of ice tumbled down the current, battering him, shoving him under. A group of his less daring companions stood on the shore waiting to see how things would turn out.

The place was Onion Portage, and for 10,000 years caribou had been coming here to cross the river at the end of their autumn migration. Artifacts show that for at least that long humans had been arriving to meet them, hunt them, process their flesh and hides and bones. It was a regular appointment, kept across millennia. And though local hunters still showed up, the caribou now were often late or didn’t come at all.

The shifting migration brought consequences for both humans and animals. In the caribou’s case, arriving later in the season meant finding a river in flux—not exactly liquid, not fully frozen. Crossing was dangerous, as the young male was learning. Waiting for freeze-up was too: Wolves and bears patrolled the forest along the riverbank. But the caribou had no choice. For days hundreds of them paced up and down the river, yards from my tent, filling the air with their musky scent and the peculiar click click click that comes as they walk, a sound thought to be made by tendons snapping over bones in their feet. They were restless and wanted only to continue their journey.

From my small vantage it seemed impossible the world would ever return to the way it had been when this route over the river, this habit of movement, was laid down in their ancestors’ minds. Already the portage itself was being transformed by new trees and shrubs that had crowded in and grown tall as the climate warmed. But I’d been told by many Indigenous people that the caribou would adjust, given time. They were curious, resilient. In the Arctic they had to be.

I looked back to the river: a chunk of ice, a blow to the head, another dunking. The young male surfaced in a spluttering fit. He decided to turn around. At the shore he shook wildly, rejoined the others. The herd turned to regard me—gray bodies, big racks, eyes wide. Then the caribou stepped up the bank and disappeared into the trees.