MUMBAI—Raginibai was at the construction site when a large police search team came looking for her. Her husband was found brutally murdered, and his body — wrapped in a gunny bag — had been buried several feet under the construction debris close by. The police suspected that Raginibai, along with a man they claimed was her “lover,” was involved in the murder. Raginibai denied this charge vehemently. But at that moment, neither her husband’s death nor the police’s suspicion could unsettle her. The well-being of her five-year-old son, who shadowed her everywhere at the construction site in Taloja, on the outskirts of Mumbai, was all that she worried about.

As a nonprofit journalism organization, we depend on your support to fund more than 170 reporting projects every year on critical global and local issues. Donate any amount today to become a Pulitzer Center Champion and receive exclusive benefits!

Ragini, a landless migrant labourer and a Dalit woman from Kalahandi — one of the most backward districts in Odisha — feared that the police would take her child away and she would never be able to see him again. In desperation, Ragini requested that the police hand her child over to a person she claimed was her sister. This was a claim that the police was legally bound to — yet never bothered to — independently ascertain.

Raginibai was arrested on November 15, 2019. She was pregnant at the time. She gave birth to a girl, her third child, inside an overcrowded Kalyan district jail, over 50 km away from Mumbai city. Her eldest, a 12-year-old daughter, was away at Raginibai’s mother’s house in Odisha at the time of the arrest. With no parental support or financial backing, her daughter had to drop out of school and is now being forced into child labour in a paddy field, many kilometres outside her village.

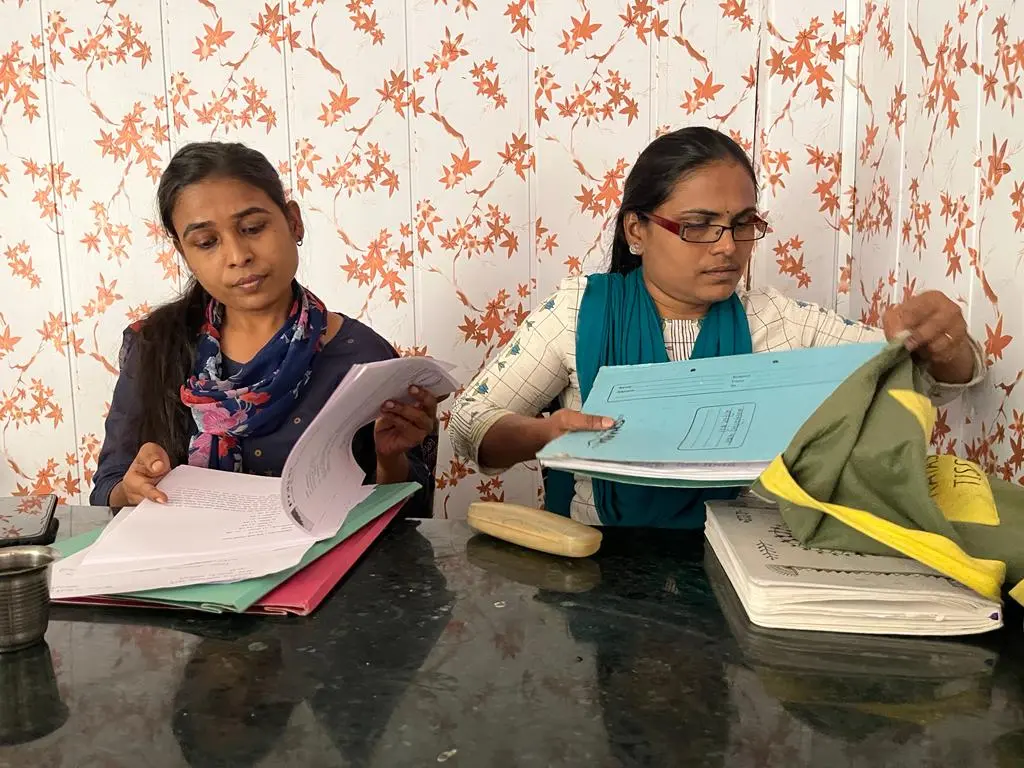

Contrary to what Raginibai had hoped for, she had no clue where her young son was until May this year. The phone number of the woman who held informal custody of her child had been “out of service” since her arrest.

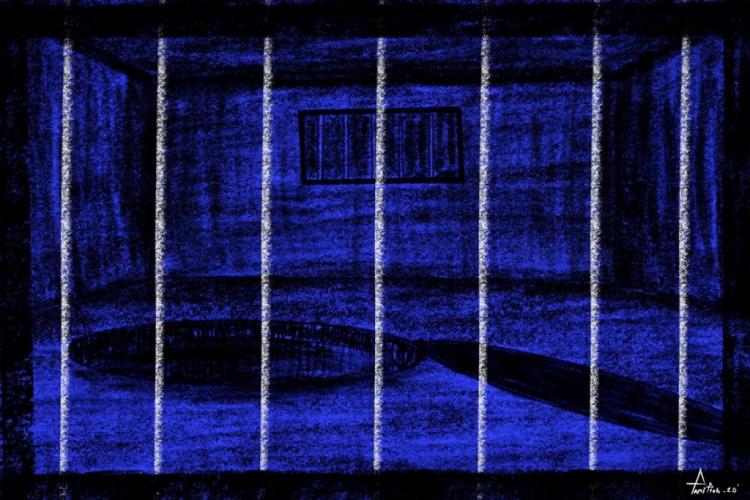

In mid-May, after hitting a stone wall, a group of paralegal and social workers associated with Prayas, a field action project of the Tata Institute of Social Sciences, decided to take things into their own hands. Two social workers — Reena Jaiswar and Vidya Torane — planned an entire search operation. But they did not inform the police. “Have they ever been of any help?” Jaiswar, a senior social worker with Prayas, asked. Raginibai had provided them with a sketchy address. “I worked at a construction site close to a highway in Taloja. There was a tall school at the edge of the highway,” she had said. “We searched the entire highway and looked for a school on the road side. And after searching for hours, and asking labourers and local shop owners, we finally ran into a woman,” Jaiswar recalled.

Torane said the woman turned out to be Raginibai’s sister. “A simple fact that took three years to establish,” Torane added. This three-year delay meant Raginibai’s son never went to school. He is eight now.

Raginibai is yet to see her child. “Her sister, worried that we would snatch the child away, went away to Kalahandi the very next day [after Jaiswar’s visit]. We are waiting for her to feel reassured and return. We have also activated our local NGO contact in Kalahandi district to ensure that the child is brought to Mumbai soon and Raginibai finally gets to meet her son,” Jaiswar said.

Raginibai’s case is concerning but certainly not uncommon, said Vijay Doiphode, a former chairperson of the Children Welfare Committee (CWC) for Mumbai. Women, at the time of their arrest, try very hard to evade any police or state control over their children. They, Doiphode said, instinctively prefer a known person over a state-run institution to take care of their young children. Doiphode, who regularly visits prisons and interacts with imprisoned women, said these are all “protective lies” that the women tell in the interest of their children. “Hence, it becomes even more important for the police to closely examine the veracity of the claims made by the women at the time of the arrest and keep both the CWC and the court informed,” Doiphode said.

A missing child, or losing custody while in prison, is the most common reality for women trapped in the criminal justice system. It is so common, Doiphode said, that it has come to be accepted as a “part of the punishment.” "Each time I would visit Byculla prisons, there would be at least 4-5 women eagerly seeking our [CWC’s] help to find out about their children’s wellbeing outside. I have regularly heard women say that they have no idea where their children are since their arrest,” he added. This situation, Doiphode said, wouldn’t arise if both the police and prison authorities did their job more proactively.

The broken system and lack of accountability can have a debilitating impact on the lives of the children of women entangled in the criminal justice system. These problems have been further exacerbated since the COVID-19 pandemic broke out in India in March 2020, sending the whole country under a forced lockdown. While welfare support systems of the most marginalised were heavily corroded, the situation for the world outside eventually eased. But inside the jail, the ugly impact of the lockdown still continues. Family visits, medical check-ups, routine court visits — a few moments that ensure that the prisoner gets to access the world outside captivity — were abruptly stopped. “Even over two years later, the situation hasn’t changed much. You will find at least a dozen women pleading to get that one mulakat (visit) with her son or daughter or to know about their well-being,” Doiphode said.

In Yerwada Central prison, Parvatibai talked about the ordeal she faced just to get her child to recognise her. When she was arrested in 2011, her daughter was barely three months old. Parvatibai, an Adivasi woman from Nanded, was moved several times from one prison to another, making it impossible for her to meet her child, who was in an institutional care. “Finally, in 2020, when I was released on a parole due to the COVID-19 pandemic, and my child was sent home too, I got to meet her in person. It took nine years for my child to just recognise me as her mother,” Parvatibai said.

Prisons are certainly not a place to raise a child. But in the absence of parental care, children below six years of age end up living with their mothers in jail. The Supreme Court of India, in the R D Upadhyay versus the State of Andhra Pradesh case of 2006, directed all states and union territories to let children live with their mothers till they turned six. The court’s rationale was that separating a child from her mother at such a young age could have a devastating impact. But once a child turns six, she is supposed to be handed over to a suitable surrogate or transferred into protective custody in a home and brought to prison to meet the mother at least once a week.

This separation, decided merely on the physical age of the child with very little attention paid to her mental state, has resulted in deep distress to both the child and the mother. In June 2018, when Sana turned 6, she was excited. As promised, the jailor kaka (uncle) bought her a yellow doll, and the jail mausis (as she called other women prisoners) cooked her favourite kheer (rice pudding).

Her mother, Ayesha, an otherwise joyful person, stayed away from the celebrations. Ayesha, in her four-year stay at the Akola district jail as a pre-trial detainee, had seen many children turn six and be sent to institutional care far away in the city. A week after Sana’s birthday party, she too was sent away.

Ayesha was soon convicted in an attempt to murder case and sentenced to 10 years of rigorous imprisonment. After conviction, she was transferred to Aurangabad central prison, over 250 km away. But Sana continues to be at an institution in Akola. Since the COVID-19 pandemic, the two haven’t had the chance to meet. Ayesha still has to serve over two more years of her jail sentence.

In her book On Women Inside, social historian and prison reform researcher Rani Dhavan Shankardass discusses the dilemmas pertaining to how to deal with the young children of imprisoned women. During her decades of work with women prisoners, she came across one case that she details in her book — three generations of women from a family in jail together in a dowry death case. While an older woman and her two daughters were convicted in the case, one of the daughters had two young children who had been brought along to the prison to stay with their mother.

During the course of her conversations with the family, particularly the younger of the two sisters, Shankardass came to realise that she was in fact a minor — and had probably only been 14 years old when she was imprisoned as an adult. When Shankardass brought this up with the girl’s mother, the mother became agitated, making it clear she had in fact known her daughter was a minor — how could she have left her teenage daughter elsewhere, while she was imprisoned? After efforts by Shankardass and her team, the girl was finally released.

In this case, Shankardass points out, the family and the criminal justice system colluded to come up with a “solution of convenience”: she couldn’t be an accompanying child, given her age, so was slotted as a convicted adult to avoid the complications of leaving her uncared for. Given the existing suspicions about shelter homes and the treatment meted out to young girls there, the family thought this was the best way forward. The state played along. Yet during her time in jail, the young woman was restless, agitated, unable to understand what was happening to her — and the prison had no way to deal with these anxieties.

The Upadhyay judgment — aligned with international standards such as the United Nation’s Rules for the Treatment of Women Prisoners (UN Bangkok Rules) and the UN Minimum Standards for Treatment of Prisoners (the Mandela Rules) — highlights 15 important aspects including health, education and overall physical and mental growth of a child in jail. But the implementation of this ruling leaves much to be desired.

An ex-prisoner, Sujata, who was incarcerated for over six years for her political ideology, shares her experience and observations from different prisons that she was lodged in across Maharashtra. Prisons, she says, break children the most. Sujata has spent many years in the Byculla women’s prison (the only “women’s prison” in Maharashtra), before being moved to the Nagpur central prison and Gondia district prison.

A few years ago, Sujata recalls, a three-year-old boy had walked into Byculla prison alongside his mother. He was a “notorious child,” Sujata said. He would play all day, jump and scream and make merry. Some movie buffs in the jail endearingly called the little boy ‘Sunny Deol’ — a yesteryear Bollywood actor.

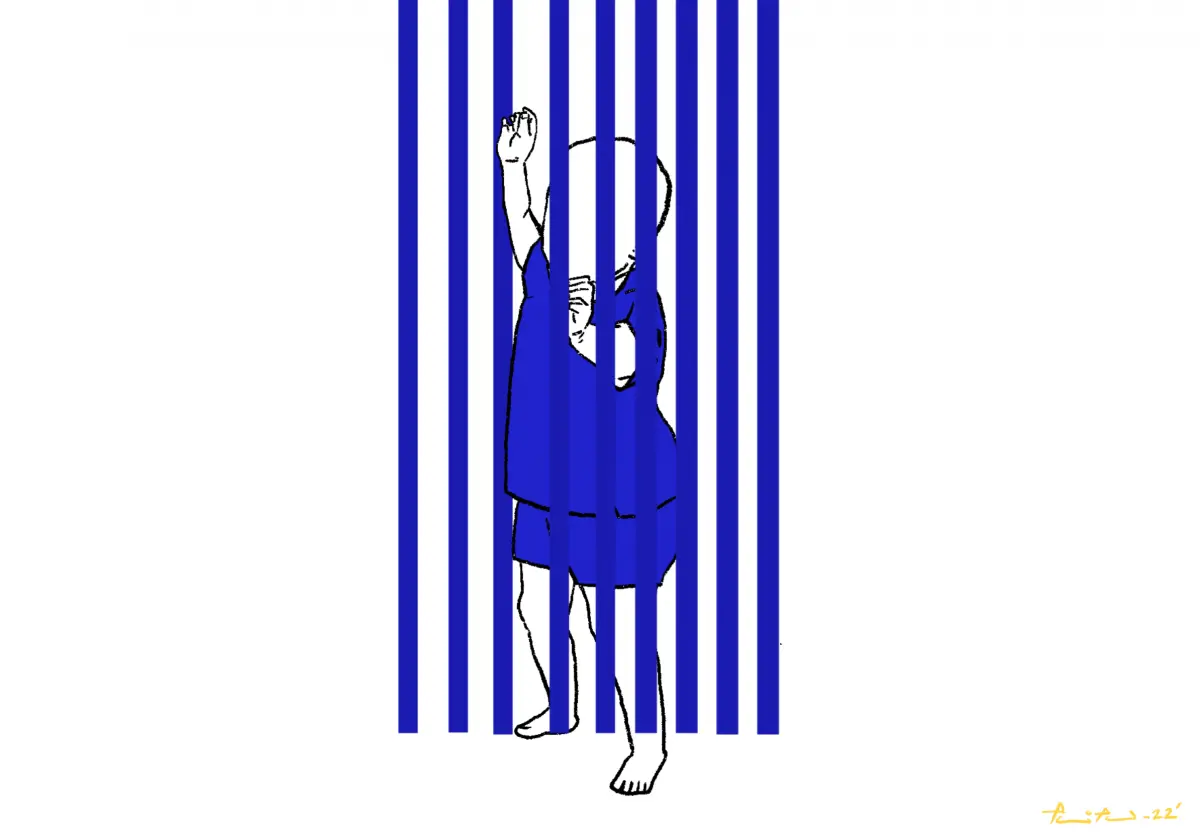

A cheerful boy otherwise, he transformed into an entirely different person by evening, Sujata says. At 5 pm, at Bandi time, or lockdown, every prisoner had to return to their respective barrack. While the adult women knew and had accepted the drill, this little boy couldn’t fathom spending the rest of his time inside an iron cage. “The moment jail staff would be seen approaching us asking to return to our respective barracks, the little boy would start screaming hysterically. He was visibly traumatised and controlling him was impossible for his mother,” Sujata recalls.

The idea of spending the next 13 hours (until the barrack gates were opened again the next day at the sunrise) petrified him so much, Sujata says, that he would clasp the iron bars and try to squeeze his body out of the narrow gaps. “It was simply heartbreaking to see him go through the same trauma every single day.” The little boy spent close to 18 months with his mother in jail, before she was finally released on bail.

The National Crime Records Bureau (NCRB), the only government agency that maintains crime and prison statistics in the country, states that around 1,700-1,800 children end up in jail along with their mothers. The recent NCRB data, published for the year 2020, states that in India’s 1,306 prisons, 20,046 women — including transgender women — are lodged. As on December 31, 2020, “1,427 women prisoners with 1,628 children are in jail,” the NCRB data indicates. This means some women have more than one child to take care of with them in jail.

With women constituting less than 4% of the total prison population, many states don’t have a dedicated prison for women. Of the 1,306 prisons in the country, only 29 are special jails for women. These jails are located in 14 states or union territories; the remaining 22 states and union territories do have not a single dedicated prison meant only to house women. States like Uttar Pradesh, Maharashtra and West Bengal, which see a large incarcerated population every year, have just one dedicated women’s prison each. It is also important to note that close to 75% of the imprisoned women belong to Scheduled Castes, Scheduled Tribes and Other Backward Classes across religions. Women belonging to the most marginalised caste identities thus face the worst of the state’s actions.

The Wire’s Jahnavi Sen, in her report on the women in Indian prisons for the series ‘Barred–The Prisons Project’, explains in detail the space struggle that women face in prisons. Although the overall occupancy rate of women in prison is much lower than men, most women’s facilities in the country, she writes, are overcrowded. In some states like West Bengal and Maharashtra, the occupancy rate is well over 130%. And when children have to share this already crammed spaces, the situation only gets worse. There is no separate space earmarked for children and their mothers; they have to make do with whatever is available to them.

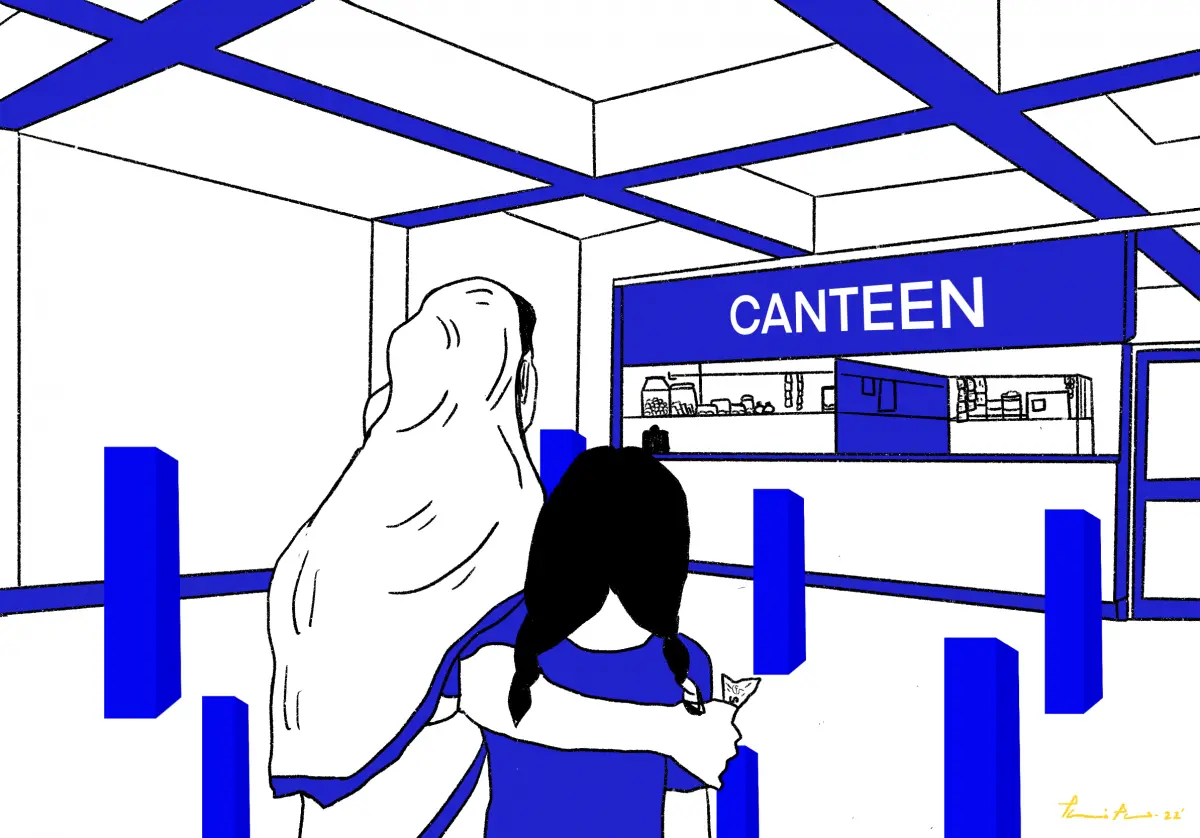

In most prisons, as prescribed in the state’s prison manual, children and pregnant women are entitled to a special diet. But much of it exists only on paper. “Also, imagine telling a growing child that she will only get 150 ml of milk, because that is what the rule book allows. Or just one fist of puffed rice can be eaten today because the prison superintendent wouldn’t allow more,” said Sujata. Most women prisoners — abandoned and penniless — don’t have money orders being sent by their families and relatives. Lack of money means they can’t buy the food sold in the jail canteens. Sujata says in those six years of prison life, she has seen far too many children being told to compromise or give up on their longing for good food.

Most mothers that The Wire spoke to said that the children had access to no games or recreation while in jail. “Even if a visiting family member or an NGO gets them a doll or a car to play with, it is confiscated by the prison staff,” said Sonu, an undertrial prisoner who spent close to six months in Pune’s Yerwada central prison. The only game that children are seen playing across prisons is Bandi or captivity. “They simply emulate what they see all day. This little game includes everything from arrest and violence to release,” Sonu said. She and her child are out now, but the Bandi game, she said, still continues.

Manual physical inspections — including pat-down search, strip search and cavity checks — are common drills in prisons. Prisoners entering and exiting prison are subjected to close scrutiny, and many women prisoners said that the prison authorities won’t spare young kids either. Shalu, a young woman, would find it agonising to see her four-year-old daughter remove her clothes right at the Byculla prison gate, every time they returned from the court visit. “My daughter knew she would be searched. It was so normalised that the child began to think that every entry or exit from the jail premise included stripping.” These children aren’t prisoners but are often treated as if they are.

In the Upadhyay judgment, the Supreme Court had ordered that a nursery or a crèche should be set up independently outside the prison. “There shall be a crèche and a nursery attached to the prison for women where the children of women prisoners will be looked after […] the prison authorities shall preferably run the said crèche and nursery outside the prison premises,” the Upadhyay judgement said in 2006. Only a few prisons followed it; many don’t till date. Professor Vijay Raghavan from the Centre for Criminology and Justice at Tata Institute of Social Sciences and Project Director, Prayas said besides Maharashtra, no other state has something as simple as an anganwadi — a child care centre system started by the Indian government way back in 1975 as part of the Integrated Child Development Services programme — working for children living with women prisoners. “In some places you do find private arrangements made by local NGOs or creches working. All of this is largely dependent on how inclined the jail superintendent is. There is no uniform system in place,” Raghavan said.

In the COVID-19 pandemic, these anganwadis were abruptly stopped. “Only a month ago, Mumbai and Thane central prison have reopened their anganwadis,” said Surekha Sale, a senior social worker with Prayas. Sale has spent the past few months trying to convince the state authorities to restart the anganwadis. “Prisons are no one’s constituencies. And among them the women and their children are the worst off,” she said, an insight gained from spending close to three decades working in prisons.

Childbirth in jails

Unlike their male counterparts, most incarcerated women face abandonment on imprisonment. And pregnant women have it much worse. If pregnant at the time of the arrest, fearing desertion and further hardship, women usually choose to undergo an abortion. But an abortion is not an easily available option. Once she steps into confinement, she loses her bodily autonomy and both the state and judiciary take over.

In early 2012, Manisha, a 32-year-old woman, was arrested for her alleged involvement in a cheating case and sent to Byculla jail. She was certain she would be out on bail in a few weeks. Manisha was in the first month of her pregnancy at that time.

An introvert, Manisha did not reveal her pregnancy to anyone, not even to her cellmates. “She would wear baggy clothes and covered herself with a shawl. Some among us saw a change in her gait but never could ask her,” said one of the former prisoners who spent several months with Manisha in Byculla prison.

Manisha, through her lawyer, applied for bail. The court rejected it. Her family, as she had feared, abandoned her. She continued to be in jail till her third trimester. During those eight months stay in jail, Manisha had managed to smuggle in many strong painkillers and razor blades, a jailor who was posted at Byculla prison in 2012 said. On the day when Manisha went into labour, “It was around 2 am,” the jailor told me. “She had slowly made her way to the toilet, and delivered the child all by herself. One woman, who was awake around that time saw Manisha in the toilet and raised alarm,” the jailor recalled. By the time the jail staff could reach the spot, Manisha had allegedly immersed the child in a bucket of water, killed it and already discarded the body in the food waste bin.

Dr. Meeran Chadha Borwankar, a retired IPS officer who was then heading the state prisons, had rushed to the prison and set up a committee to look into the matter. Recalling the decade-old incident, Borwankar said Manisha’s pregnancy could go unnoticed only because of overcrowding. “Overcrowding of prisons (including of Byculla women’s prison) has meant that most of the jail authorities’ time is spent on administration, documentation and court work.”

Manisha’s incident pushed the state prison authorities to take many concrete measures. “While action was taken against the officials found negligent, we had also strengthened our system of information collection from among inmates through the buddy system i.e., prisoners to look after each other’s physical and emotional wellbeing,” Borwankar shared. These measures, she said, also proved to be of a considerable help in tackling the prevalent suicide cases.

Within a few years, in 2016, the Bombay high court directed the prison authorities to not wait for court orders if a woman wishes to undergo an abortion. “A woman’s decision to terminate a pregnancy is not frivolous. Abortion is often the only way out of a very difficult situation for a woman […] the law bestows a very precious right to a pregnant woman to say no to motherhood,” the division bench of Justice V.K. Tahilramani and Justice Mridula Bhatkar, in 2016, observed. The order, however, has not changed much for pregnant women in prison. “It is virtually impossible for women to take a call (to abort). The same legal and administrative process is followed, virtually making it impossible for her to abort the child within the stipulated time,” Jaiswar explained.

The brutal impacts of the carceral system continue to wreck lives even after the children have stepped out of prison with their mothers. Especially in the case of those born in jail, it becomes virtually impossible to shed the prison stamp.

Muskan was born in Kalyan’s Adarwadi jail in 2015. She spent time in jail for close to four years with her mother, booked on charges of murder. Finally, the trial court acquitted her and both Muskan and her mother were out. But Muskan’s real predicament began when her mother tried to get her birth certificate changed. “The certificate mentions Aadharwadi as her place of birth,” her mother said. Since their release, Muskan’s mother said that she has petitioned almost every government office she knew to get the birth certificate altered. “Once I get her admitted in a school with a document that mentions jail as her place of birth, that would be like a permanent imprint. I can’t let that happen,” her mother said. The Upadhyay judgement states that the mother’s residential address should be added to the child’s place of birth, but that just doesn’t happen, Sale explained.

Sale and her team of social workers have been wading through the rigid government functioning and trying to appeal to the district administration to ensure children aren’t forever criminalised. Their efforts have led to small changes being made. For instance, the Thane Child Welfare Committee issued an order early July to all hospitals under its jurisdiction to undo the wrong done to children. But this, Sale said, will take a long time before it is implemented.

Until then, Muskan, who is over seven years old now, won’t be going to school.

Names of prisoners and their children have been changed to protect their identities.