“Your brother is not going to return, señorita.”

Mariana’s hands shook as she read the message she had just received over Facebook Messenger. It came from a person she didn’t know, who used a horse head for a profile picture.

She typed out a quick response: “Excuse me, how do you know? Why would you say that?”

It was March 2017 and two days earlier, Mariana’s mother, who lived in the state of Guerrero in southwest Mexico, had called Mariana in a panic. Her mother said members of a criminal group had kidnapped Mariana’s brother, 27-year-old Roberto, just 10 minutes earlier.

Mariana and Roberto were very close. Mariana once sold clothing at the market in their hometown of Chilapa de Álvarez, where she said she was extorted by a criminal group. She fled Guerrero in 2015 and sought asylum in the United States, so she and Roberto kept in touch over WhatsApp. He would share photos of himself with his two sons on his lap, and selfies, grinning and giving a thumbs up. Just the day before, he had sent her pictures from his family’s recent vacation in Acapulco.

Because she was living in Oregon’s Willamette Valley and couldn’t help search for her brother, Mariana enlisted the help of her social network. She posted about Roberto’s disappearance on Facebook and included a recent photo of him. She hoped one of her friends or relatives in Guerrero had seen him and had information.

But instead of getting a tip about Roberto’s whereabouts, she got the threat from the person with the horse head avatar.

“If you all don’t pay today, they are going to kill him,” the person said.

He demanded about $3,700 and provided several Mexican bank account numbers. Mariana deposited the money and waited.

In 2006, before social media use exploded around the world, Mexican President Felipe Calderón launched a war against drug traffickers. But as the drug war intensified and social media became more widespread, cartels and their affiliates learned to use the platforms as tools for intimidation, extortion and propaganda. Today, criminal groups across the country share posts and videos intended to recruit members and instill fear in enemies. And as Mariana found, these global platforms allow cartels to easily extend their reach across international borders, to demand money and menace those who stand in their way.

In Guerrero, criminal groups create fake accounts and post hit lists on Facebook and WhatsApp, using nicknames and crude language to describe their targets. They also extort people, as they did in late November, when schools across the state closed for a month after criminal organizations threatened teachers over WhatsApp and demanded the instructors hand over a portion of their end-of-year bonuses.

“It’s very reasonable to think that if these people are fighting on the land, they’re going to fight in cyberspace,” said Guadalupe Correa-Cabrera, an expert in U.S.-Mexico relations and organized crime at George Mason University.

Mexican civilians are getting ensnared in the criminal groups’ cyber wars. People have fled their homes, and some have even left the country, after accounts associated with delinquent groups threatened them on social media. For some, the death threats and extortion attempts have continued even after they began the asylum process in the United States.

The number of Mexicans seeking asylum in the United States has increased by more than two-and-a-half times since 2014, according to Syracuse University’s Transactional Records Access Clearinghouse, or TRAC. Social media threats are becoming a more common type of evidence in such cases, according to Tania Nunez Amador, an immigration attorney based in Culver City, California For her Mexican asylum clients, most of whom are from Guerrero and Michoacán, virtual threats were often “the breaking point,” she said, that finally spurred them to flee and seek refuge in the United States.

Amador said criminal groups had threatened several of her clients—in person and through letters and phone calls—and said they had information about her clients’ schedules, addresses and families. Those interactions were intimidating, but when her clients received subsequent threats over social media, they viewed the threats as proof that the groups were, literally, following them, she said.

“I think what makes it scary is if someone is willing to find you on social media, it might seem like they actually know who you are,” Amador said. “They might know everything about you, if they were able to find you on social media.”

Facebook’s community standards prohibit people or groups involved in violent activities, such as terrorism, organized crime or human trafficking, from using the platform. A company spokesperson, who agreed to comment on the condition that their name not be published, citing “safety concerns,” said Facebook offers “robust reporting tools,” so people can flag content that violates the site’s policies.

The spokesperson said the company has about 15,000 people who rapidly review posts and remove content that violates its standards. The spokesperson said the moderators review content in more than 50 languages, but declined to say how many of the content moderators speak Spanish or review content in Mexico.

"I think what makes it scary is if someone is willing to find you on social media, it might seem like they actually know who you are. They might know everything about you, if they were able to find you on social media."

—Tania Nunez Amador, an immigration attorney based in Culver City, California

Despite such efforts, accounts associated with Mexican criminal groups continue harassing individuals and communities. Nilda García, a professor at Texas A&M International University in Laredo, who wrote her dissertation about the use of social media in the drug war, noted that social media sites have aggressively targeted accounts linked to Islamic extremist groups, at times at the urging of the U.S. government.

She said she hasn’t heard of the Mexican government applying similar pressure to social media companies, yet she said the companies should more vigilantly track and remove accounts linked to Mexican criminal groups.

Both ISIS and Mexican criminal organizations use these platforms for the same purpose, she said: “To get to people, to get more followers, to get into their hearts and minds.” The Mexican criminal groups are not terrorists, she said, “but at the same time, they recruit people and they become sicarios and they become kidnappers and they become delinquents.”

Vital journalism or glorification?

As part of her dissertation, García conducted a detailed analysis of various cartels’ use of Facebook, Twitter and YouTube.

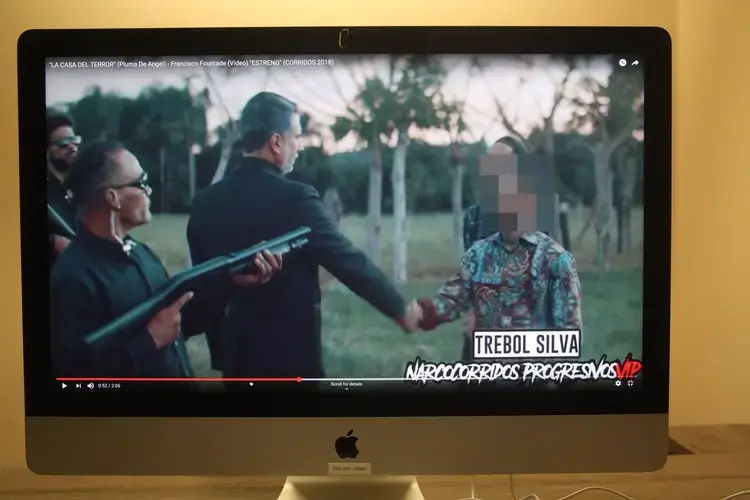

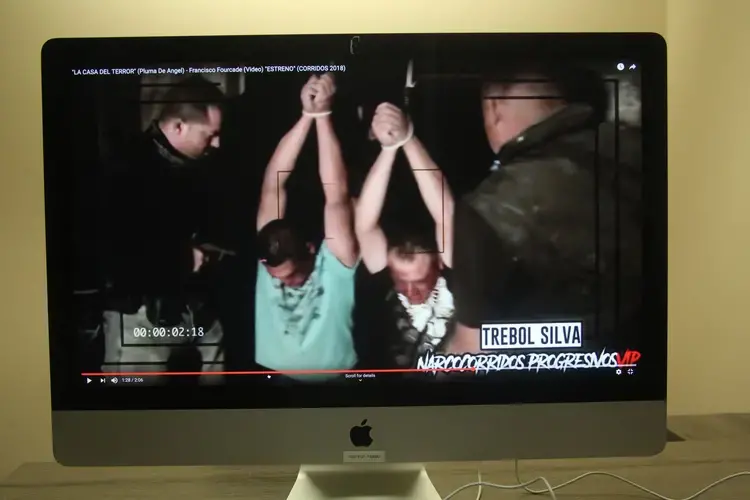

She found cartels use videos to share everything from news and music videos about the groups, to threats, shootings and executions. One type of video shows cartel members pointing weapons at captured members of rival cartels and interrogating them. YouTube took down three such videos—including one with more than 1.78 million views—after The Desert Sun inquired about them.

In a statement responding to such videos, a YouTube spokesperson said the company strives to ensure human rights activists and citizen journalists have a voice on the platform, while also ensuring that videos on its site don’t promote or incite violence.

“Depending on the uploader and the additional context they provide,” the spokesperson said, “a video featuring a violent group may be documentary in nature and represent vital journalism, or may be glorification of violence that would violate our guidelines.”

The spokesperson said company policies prohibit gangs, cartels and terrorist groups from owning a YouTube channel or uploading content. The spokesperson said they use “sophisticated smart detection flagging technology, flagging from experts and users, and human review to determine context, like whether the video is intended to incite violence or document atrocities.”

Cartels also use social media as a public relations ploy. Garcia pointed to a 2013 video of Gulf cartel members distributing food and clothes to hurricane victims. Captions on one video, set to hip-hop music, read, “they have been good people, in the good and bad times,” and, “if they help, it’s because they have heart.” It’s been viewed more than 506,000 times.

People associated with the Sinaloa cartel, meanwhile, post videos of narcocorridos—literally translated as drug ballads—and images of their vehicles, weapons and piles of money to glamorize their lifestyles. One music video, viewed more than 2.5 million times on YouTube, features a male singer celebrating convicted cartel kingpin Joaquín “El Chapo” Guzmán. Dancing behind him are three women, wearing short black dresses and face coverings that only reveal their eyes.

Criminal groups also retaliate against civilians who use social media to post witness accounts of blockades and shootouts between rival cartels. For example, in 2014, Dr. María del Rosario Fuentes Rubio, who was an administrator for the Twitter and Facebook accounts of Courage for Tamaulipas, a popular news source that shared information about drug-related violence in the Gulf Coast state, was kidnapped. Her captors reportedly posted several tweets on her personal Twitter page announcing her impending death and warning others to stop reporting on the cartel-related violence.

“I can only tell you not to make the same mistake I did, it doesn’t benefit you, quite the opposite I realize today,” her captors wrote in all capitals letters. The final message on her account, again in all capitals, warned other Twitter users who contribute to Courage for Tamaulipas to close their accounts and said, “do not put your families at risk, like I did, I plead for their forgiveness.”

Then they posted a photo of her, dead and bloodied. Her account has since been closed.

‘My family and I had to leave’

In the violent city of Chilapa, in Guerrero, criminal organizations use social media to target individual people, and residents have learned to take the threats seriously.

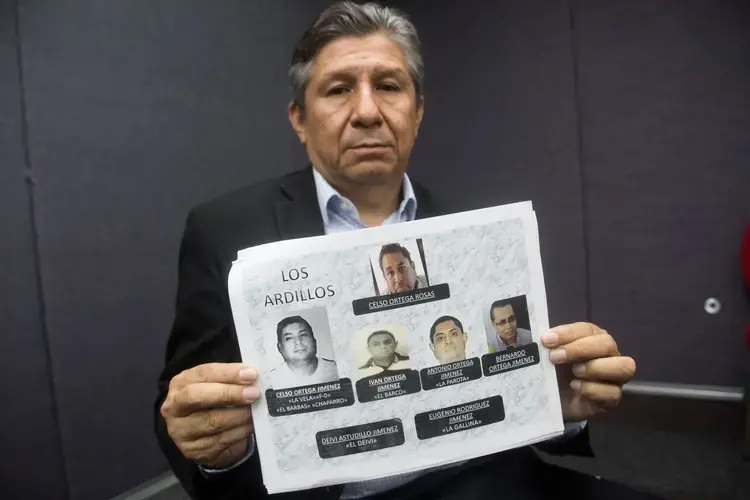

Two groups, Los Rojos and Los Ardillos, have been fighting over Mariana’s hometown of Chilapa, the gateway to Guerrero’s poppy-rich mountain region, since 2014. The war between the two groups has had bloody consequences. In 2017, the municipio of Chilapa, the equivalent of a county in Mexico’s political system, had the second highest homicide rate among municipios in Mexico, with 134.8 homicides per 100,000 people, according to Citizen Council for Public Security and Criminal Justice, a Mexico City-based advocacy group.

Sometimes, the groups announce on social media whom they intend to kill. Using false profiles, they publish online hit lists, in which they identify their targets by a first name or nickname, according to screenshots shared with The Desert Sun. The often crude and vulgar messages are frequently written in all capital letters and include spelling errors and street slang.

People have learned to take the lists seriously, said Romina, a former Chilapa resident who is now seeking asylum in the United States.

“At first, when the lists started appearing, people just went about their daily lives,” she said. “They figured since they were not involved in crime, they had nothing to fear. But unfortunately, they started killing people and we quickly recognized that being on one of these lists was going to get you killed.”

José Díaz Navarro, who leads a Guerrero-based victims advocacy group called Siempre Vivos, or Always Alive, agreed.

“If someone’s name appears on the list and they don’t leave Chilapa, without a doubt the next day or very soon after they will appear dead or missing,” he said.

Díaz Navarro said he has been targeted by Los Ardillos since 2014, when he reported to police that members of the group had kidnapped and killed two of his brothers. As a result of his public accusations, Díaz Navarro said his name has appeared on online hit lists nearly 30 times. He fled Chilapa in 2016 and only returns with the protection of the federal police.

At least one person from Chilapa said he considered the hit lists to be such serious threats that he fled the city—and eventually, the country. Martín, who owned a business in Chilapa, said Los Ardillos posted his name on a Facebook list in 2016. He said they referred to him by his nickname and using obscenities, said they were going to abduct and kill him. Martín was at home when he read the message. He said he was shocked and terrified.

Martín had been threatened before. As a business owner who sold clothing and phone accessories in Chilapa, he said he was extorted by Los Rojos for eight years. Later, he was threatened by Los Ardillos for trying to investigate the death of his nephew, he said, but appearing on the online hit list was the final straw. The Desert Sun was unable to review the post.

“My family and I had to leave the city that day,” he said.

They fled Guerrero by car, taking little with them.

The group included Martín’s name on two more lists over the next year, making him feel as if he would not be safe anywhere in Mexico. A year after he was first threatened on Facebook, he and his family sought asylum in the U.S.

As part of his asylum case, Martín told the immigration judge criminal organizations extorted and threatened him in Guerrero, he said. He told the judge about family members who had been killed, but he said he never testified about his name appearing on the lists. He worried the judge would get the wrong idea.

“If I presented information about the lists, it’s possible they would have thought I had something to do with one of the groups,” said Martín, who was granted asylum in 2018.

Unlike Martín, Romina included an example of an online threat in her asylum application, as proof that she would be in danger if she returned to Mexico.

Romina said Los Ardillos added her father’s name to a list on Facebook and WhatsApp in 2016 and accused him of working for Los Rojos. Her father’s name appeared on lists on the two platforms again a year later.

He was kidnapped and killed in June 2017. She fled the city several days later, eventually seeking asylum in the United States. She had been in the U.S. for more than a year when a criminal group included her name on a hit list on WhatsApp. In the message, the group threatened Romina, who is a transgender woman.

“We are going to find you,” they wrote in all capital letters, referring to her by her masculine name and a homophobic slur. She shared the message with The Desert Sun.

WhatsApp, which is owned by Facebook, encourages users to report problematic content and says users should contact law enforcement if they believe they are in physical danger. A WhatsApp spokesperson, who declined to comment for this story, referred The Desert Sun to the company’s Terms of Service and safety tips on its website.

“Submitting content (in the status, profile photos or messages) that is illegal, obscene, defamatory, threatening, intimidating, harassing, hateful, racially or ethnically offensive, or instigates or encourages conduct that would be illegal, or otherwise inappropriate violates our Terms of Service,” according to the company’s website. “We will ban a user if we believe that user is violating our Terms of Service.”

The spokesperson would not disclose the number of users who have been banned in Mexico.

Cartels are using social media to recruit and to track and murder enemies. The town of Chilapa, Guerrero, Mexico faces the wrath of dangerous drug cartels both on the streets and online. Video courtesy of The Desert Sun.

‘You have to pay’

Two years before the man with the horse head avatar demanded a ransom, Mariana was facing extortion demands at her clothing stand in Guerrero. She paid Los Rojos about $75 each week in protection money, she said. It was the price of doing business in Chilapa.

But in 2015, Mariana’s sales dropped. She missed three or four payments to the group, she said. And men from the group started making threatening comments that disturbed her. One said he knew she had a daughter; she took that to mean her little girl was in danger. Another said if she couldn’t pay the fee, she could pay “another way,” which she interpreted to mean sex.

Given the threats, Mariana grew increasingly nervous about opening and closing her stand by herself. One day, she arrived at her stand and found an armed man on a motorcycle waiting for her to pay her dues. Mariana worried the group was following her. She was scared and didn’t know what the group might do. She wanted to hide, but thought Chilapa was too small. So she and her cousin fled to Mexico City and then Tijuana, where they sought asylum in the United States in April 2015.

Once allowed into the United States, Mariana stayed with relatives in Texas, Florida and then Oregon. Some had come years ago as economic migrants. Others had left Guerrero more recently, as a result of the drug-related violence. As of early 2019, Mariana’s asylum case is still making its way through the courts. Her next court date is in 2020.

Mariana was at her aunt’s house in Oregon when her mother called with the news of her brother’s disappearance. Mariana said she tried calling and messaging Roberto. He didn’t respond.

Two days later, Mariana got the first extortion message over Facebook Messenger. The person threatened that if Mariana’s family didn’t pay the ransom, Roberto would be killed, with pieces of his body left in black bags. Mariana desperately wanted to help Roberto get home safely.

Mariana was skeptical that the person on the other end of the conversation actually had her brother. She tried asking for proof, but never got it.

“They are going to let your brother go free but you have to pay,” the extortionist said. “If not, they’ll kill him.”

“I’m going to start collecting the money,” she wrote. The extortionist “liked” her message.

In spite of their doubts, Mariana and her relatives in Oregon scrambled to pull together the ransom. Mariana said she contributed nearly everything she had. She said she was left with hardly enough money to buy groceries.

“We were all hopeful that we would find him,” Mariana said.

Mariana and her family came up with about $3,200 — about $500 short. The person with the horse head avatar told Mariana it would suffice.

Sometimes, the agony of communicating with her brother’s maybe-kidnappers overwhelmed her. Her hands shook and her head ached as she read the messages and imagined her brother being detained or tortured. When it was too much for her, she would hand her phone to her cousins and ask them to continue the conversation.

Two days after she received the first Facebook message, Mariana pleaded for information about her brother.

“Please, I beg you, I don’t know anything about my brother,” she wrote. “Give me something, please. Help me. I’m trusting you.”

“We left him in Trigomila,” came the response, referring to a small city in the municipio of Chilapa.

Mariana’s relatives in Guerrero searched for Roberto in Trigomila, but didn’t find him.

Two days later, she got another message from the extortionist: “What’s going on?”

She didn’t respond.

The Desert Sun provided Facebook with verbatim excerpts of Mariana’s conversation with the person with the horse head avatar but, to protect the safety of Mariana and her family in Guerrero, did not provide the company with screenshots of the conversation, which would have revealed the names on the accounts.

A Facebook spokesperson said the company’s policies prohibit users from facilitating or coordinating activity intended to cause real-world harm. Responding to the text excerpts shared by The Desert Sun, the spokesperson said, “in the case that someone received these messages in this situation and it was reported to us, we indeed would remove it and take action against the person who sent the messages because this violates our Coordinating Harm Policy. That is why we strongly encourage people to report this to us so that we can take action.”

Users have the options to block or mute people whom they don’t want to see or communicate with, the spokesperson said, adding that users should contact law enforcement if they think authorities should intervene.

“In my case, I didn’t block him because I was hopeful he had my brother,” Mariana said. She said she finally blocked him six months later.

Little recourse

Mariana said she alerted police in Oregon, but they told her they couldn’t do anything. They told her the threat was out of their jurisdiction, she said, as it came from a Mexican phone number. She said she never considered reporting the issue to Facebook.

Facebook should do more to protect its users, Mariana said, “so what happened to us doesn’t happen to others. If this happens to you, it’s terrible.”

Social media platforms’ responses to ISIS and and other extremist groups could offer some lessons for tackling Mexican criminal groups’ online abuses, experts say.

Several years ago, Islamic extremist groups regularly used mainstream social media platforms, like Facebook and Twitter, to show off their battlefield victories, publicize their progress on the ground and promote their ideology, said Alexandra Siegel, a postdoctoral researcher at Stanford University, who uses social media data to study conflict dynamics in the Middle East. The extremists threatened governments or leaders of other groups, but didn’t regularly leverage personal attacks, she said.

She said the U.S. and other governments pressured the platforms to remove the accounts, citing issues of national security. Around 2015, she said, the companies stepped up their efforts to ban accounts believed to be associated with ISIS and other groups. That’s led to a cat-and-mouse situation, she said, where small, anonymous accounts pop up until they’re banned again.

There may be unintended consequences to this policy, Siegel said. By banning extremist accounts, platforms limit the number of everyday users that might be exposed to their content, she said. But that doesn’t mean the content disappears for good.

“It often doesn’t go away, it just moves to more difficult-to-track, private or highly specialized platforms,” she said, such as private messaging channels or so-called Dark Web communities, where radical content and violent narratives are less likely to be censored or banned.

"It often doesn't go away, it just moves to more difficult-to-track, private or highly specialized platforms."

—Alexandra Siegel, about the extremist content

The Central Intelligence Agency is investing more heavily in its counter-narcotics effort abroad, to stop the flow of drugs into the country, director Gina Haspel said in a speech in September. The agency generally collects intelligence through classified and publicly available information, including social media, but a spokesperson declined to comment on what specific accounts it reviews or what information its acquired from them.

A spokesperson for the Federal Bureau of Investigation said it does not discuss any investigative or operational techniques. The U.S. Departments of Justice and Homeland Security did not respond to requests for comment on whether they monitor Mexican cartel activity on social media.

García, the Texas A&M International University professor, suggested that social media companies might consider the cartels less of a threat than Islamic extremist groups because their influence and violence is centralized in Mexico.

“It’s not affecting other countries as much,” she said of the violence. “It’s not something that’s recognized worldwide.”

But given social media’s international reach, Mexican criminal organizations’ online threats are not confined to Mexico’s borders.

About two weeks after Mariana paid the ransom for her brother, a family friend told Mariana’s mother that officials had found a dead body in a well in Guerrero. The person’s disembodied limbs, swollen and decomposing, were in black bags, Mariana said, just as the person with the horse head avatar had promised.

Mariana’s family later identified Roberto’s body using DNA. She said they never found Roberto’s torso. They are resigned in their belief that they will never know who the person from Facebook Messenger was, or if they were involved in the kidnapping or killing of her brother.

Six months after Mariana received the first message from the extortionist, she received a message out of the blue from him asking, “what did your brother tell you?”

Again, Mariana didn’t respond. She felt deceived. She didn’t know which part of the story—if any—was true.

She deleted her Facebook profile and made a new account. Now she uses a nickname and never posts photos of herself or her kids. She rarely uses Facebook Messenger. Today, she’s more cautious about who she communicates with. Rather than use Facebook, she prefers to text message, over WhatsApp, with just a few family members in Mexico.

“I hardly chat with anybody,” she said. “It makes me scared.”