For a moment, Rabbi Rachel Schmelkin imagined that after Aug. 13, 2017, life would go back to normal.

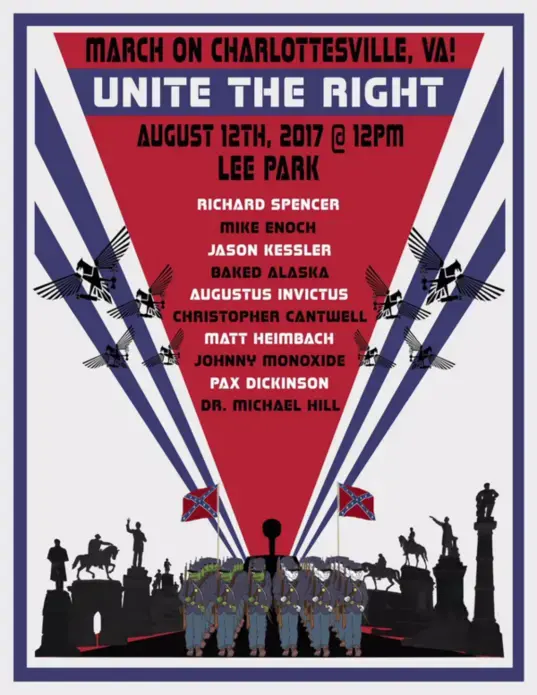

The day before, hundreds of white nationalists had descended on Charlottesville, Virginia, where she was an associate rabbi at Congregation Beth Israel. They carried torches, chanted racist slogans and tore through crowds with flags pointed like spears. A night’s sleep, she had hoped, would expel the trauma she had witnessed.

“The Unite the Right rally was the most terrifying experience of my entire life,” Schmelkin said. “I had never seen extremism like that up close and I never feared for my safety as a Jewish person. It changed me.”

As a nonprofit journalism organization, we depend on your support to fund more than 170 reporting projects every year on critical global and local issues. Donate any amount today to become a Pulitzer Center Champion and receive exclusive benefits!

But four years later, sitting in her new home more than 100 miles away from Charlottesville, she reads news accounts of the court verdict in a civil case stemming from the rally, and acknowledges she still marks time by before and after.

Since that searing summer day, Schmelkin, 33, has devoted herself to better understanding what happened and working to make sure it never happens again. Soon after, she left her position at Congregation Beth Israel for a job with the One America Movement, a nonprofit dedicated to building relationships between people who wouldn’t otherwise talk to one another.

Charlottesville taught her many of the lessons she uses in her new work. Now senior manager of Jewish programming at One America, she trains rabbis, cantors and other Jewish professionals about the neuroscience and psychology of social divisions and how to create healthy and constructive dialogue.

“I actually think the key is to come together across differences and not be afraid to try to build relationships,” said Schmelkin. “I’m not going to sit down with someone who wants to harm me. But there are people with whom I can sit down, even though I might feel uncomfortable.”

For Jews and people of other minority faiths, the events in Charlottesville, which resulted in the deaths of three people and injuries to more than 50, were the first in a series of wake-up calls about the rise of white nationalism.

It also brought into sharp relief a reality many hadn’t before considered — that white nationalism is at its root antisemitic.

With its notions of white identity, racial superiority, fear of immigrants and its traditional Christian beliefs, white nationalism is also profoundly anti-Jewish. Many white nationalists portray Jews as infiltrators, global elites or puppet masters secretly controlling the strings of power. A classic example are conspiracy theories surrounding billionaire philanthropist George Soros, who has been accused of funding Black Lives Matter and antifa protests.

Such conspiracy theories apparently led a man to kill 11 Jews at the Tree of Life synagogue in Pittsburgh in 2018. Authorities say that Robert Bowers, a onetime bakery delivery driver, was a white nationalist whose fears of white genocide through immigration caused him to zoom in on HIAS, a Jewish-led organization that settles refugees of all faiths. One of the congregations that met at Tree of Life supported HIAS’ work.

“HIAS likes to bring invaders in that kill our people,” Bowers posted to the website Gab the morning of the attack. “I can’t sit by and watch my people get slaughtered. Screw your optics. I’m going in.”

On Jan. 6, 2021, when an angry mob stormed the U.S. Capitol in an effort to thwart Congress’ confirmation of President Joe Biden’s election, some wore T-shirts proclaiming “Camp Auschwitz” or “6MWE,” an antisemitic dog whistle that stands for “6 million wasn’t enough.”

“We’re just coming into an awareness of how this movement directly endangers Jewish lives — in addition to growing our awareness of the ways this movement endangers democracy and the lives of Black and brown people and LGBTQ people,” said Sharon Brous, senior rabbi of IKAR, a Jewish congregation in Los Angeles.

Jews have always known of the existence of white supremacists and neo-Nazis in America. What changed in the past few years is that white nationalism is no longer fringe.

“More and more everyday people, and particularly people who identify with the Republican Party, are adopting this white nationalism worldview,” said Stosh Cotler, CEO of Bend the Arc, a liberal Jewish group that blends advocacy and political organizing. “Many of us are literally in the crosshairs of white nationalists who don’t see us as having a valid place in the country.”

A recent survey from the Public Religion Research Institute found that 57% of white evangelicals indicate they’d prefer the U.S. be a nation primarily made up of people of the Christian faith.

Perhaps more disturbing, 26% of white evangelicals said they believed that violence may be necessary to save the country; that number climbed to 39% among white evangelicals who believe the election was stolen from former President Donald Trump.

Aryeh Tuchman, senior associate director of the Anti-Defamation League’s Center on Extremism, sees what he calls a “blurring of the lines” between self-identified extremists and white Christian nationalists. That has made the work of the center, which employs a staff of 25, more difficult.

“We’re living in a world where the commitment to maintaining a shared center or public sphere that is free from violence, fear and bigotry has eroded,” Tuchman said. “We’re seeing the politicization of every element of our society, including the fight against antisemitism. That’s a fundamental shift.”

It fell first to the Jewish community of Charlottesville to figure out what was going on.

“We had to answer the questions of our children the very next day: Why were there people on the street saying ‘Jews will not replace us,’ and why do they hate the Jews?” said Tom Gutherz, the senior rabbi at Congregation Beth Israel. “These were questions that were not asked before.”

Schmelkin and her husband, Geoff, moved to Charlottesville in 2016, thinking it would be a relaxed college town with a small Jewish community. Rachel had completed seminary and was ordained a rabbi. Geoff had been accepted to the MBA program at the University of Virginia.

But not long after they settled in, the Ku Klux Klan held a rally. Then came news reports that white supremacists sought a permit to rally in opposition to the Charlottesville City Council’s vote to remove the statue of Confederate Gen. Robert E. Lee and rename Lee Park.

A congregant sent Schmelkin a story from The Daily Stormer, a neo-Nazi website, that read, “Next stop Charlottesville; final stop Auschwitz.”

Leaders of Congregation Beth Israel, housed in a 138-year-old, Gothic revival building in Charlottesville’s historic downtown, sprang into action. They conducted security assessments. They hired a guard. They decided to relocate several Torah scrolls, including a Czech Torah that had survived the Holocaust.

On the day of the rally, the congregation held Saturday morning services an hour earlier so members could get home safely.

Schmelkin, who plays the guitar, had planned to attend a counterprotest on the steps of First United Methodist Church that morning to sing folk songs and Jewish songs of peace — “Turning of the World,” “We Shall Not Be Moved” and “Olam Chesed Yibaneh,” Hebrew for “The world shall be built from kindness.”

She ended up performing only two.

Fifteen minutes into her singing, the church went into lockdown. The rally had been disbanded by police, a state of emergency declared and hundreds of white nationalists were packing the streets. In the melee, the Schmelkins drove an injured woman to the hospital.

The following days brought little relief.

For months afterward, white nationalists continued to flock to Charlottesville. The white nationalist leader Richard Spencer led an October torch rally a block from the synagogue’s Sukkot celebration. There were court hearings and trials for white supremacists such as James Alex Fields Jr., who rammed his car into a crowd, killing Heather Heyer. (Fields was found guilty and sentenced to life in prison.)

“We were often on edge and felt like the synagogue should be on high alert,” Schmelkin said.

Shortly after the rally, Andrew Hanauer, the president and CEO of One America Movement, came to Charlottesville to start a clergy group willing to think through what had happened and train people to cross divides. The group included white evangelical pastors, a Black pastor, a lay leader from the mosque and two rabbis.

“The rally could have led me to go into my own silos, retreat into my liberal circles and develop a fear and dislike for people who think differently from me,” Schmelkin said. “I made a concerted effort not to go in that direction.”

The work of the group felt transformative, and she began to feel a tug to do more.

After her husband completed his degree, Schmelkin joined One America full time. She has led Jews to explore polarization and bridge building and brought together a group of progressive Jews and evangelical Christians in northern Virginia.

She praised the verdict that found Unite the Right organizers liable for injuries suffered by counterprotesters, and awarded $26 million in damages. (The jury deadlocked on two federal conspiracy charges.)

“This is a move in the right direction — saying loud and clear to white supremacists and neo-Nazis that there is a price to pay for hatred, violence and intent to harm,” she said.

But she also knows the work she is doing is far from complete.

“It feels like the right thing to do — to bring the lessons I learned to other people and use them for the purpose of bettering our country,” Schmelkin said. “It feels like a calling.”