Every year in Cameroon, wealthy Americans, Europeans, and Russians pay huge amounts of money to hunt elephant, buffalo, or bongo. But local populations, such as the Baka in the southeast, do not benefit: Not only do they receive a tiny share of the spoils, but they are also denied access to privatized hunting zones, which are essential to their survival.

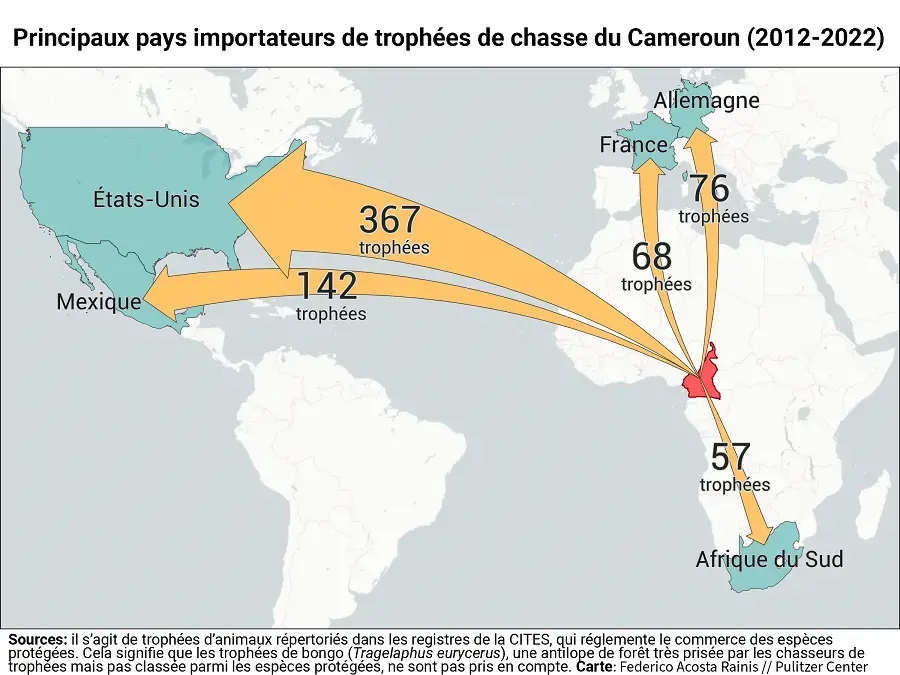

Honoré Ndjinawé may speak soberly, but you can feel his dull anger when he talks about the trophy hunts organized around Dissassoue, a small hamlet in the extreme southeastern forest region of Cameroon, where he lives. Colonial in origin, this practice, also known as "sport hunting," consists of killing a large, rare wild animal for pleasure, and keeping part of its remains to show off. The United States is the leading importer of trophies from Cameroon, followed by Mexico, Germany, and France, according to data from the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES). For the period 2012-2022, for example, 1,063 trophies of protected species left Cameroon, including 367 to the USA, 142 to Mexico, 76 to Germany, and 68 to France.

What revolts Honoré Ndjinawé is not so much the activity itself as its impact on the Baka, the indigenous people to whom he belongs and who have inhabited the exceptionally biodiverse forests of this part of Cameroon since time immemorial, living from fishing, hunting, and gathering. Sitting under a shelter made of wood and straw, the young man lists the difficulties it causes in this region, three days' drive from the capital, Yaoundé.

Part of the Moloundou district, Dissassoue borders a 54,000-hectare hunting area that has been leased for the past 16 years to Mayo Oldiri, a Spanish-owned company with a French hunting guide. Its inhabitants would like to be able to enter this area of forest outside the hunting season, which runs from April to July. "But we can't go there to fish, hunt, or look for non-timber forest products. We can't because the company's employees stop us, seize our equipment, and take it to their base," reports Honoré Ndjinawé.

"But what we want to take from the forest is only what we need to live," says the 30-year-old, who is also vice-president of the Sanguia baka Buma'a Kpode (Asbabuk) association of Baka communities. "If we don't feed ourselves, we'll die!"

Stays cost over 40,000 euros

The reality described by Honoré Ndjinawé stands in stark contrast to that sold by the hunting companies and guides operating in Cameroon, most of whom are of foreign origin. These "safaris," as the locals call them, are aimed at a wealthy clientele living in Europe, the USA, Mexico, or Russia, and offer them a comfortable, protected setting in which to shoot a buffalo, a large forest antelope known as a bongo, or even an elephant, a species partly protected in the country and considered threatened with extinction by CITES. "Each professional hunter has his own vehicle and a team of trackers and porters," announces the Mayo Oldiri website, which also publishes photos of clients posing alongside freshly slaughtered animals, and others showing the well-appointed camps where they stay.

Mayo Oldiri, which bills itself as the largest hunting company in Cameroon and claims to control over a million hectares, sells two-week bongo stalking holidays at prices ranging from 42,000 to 53,000 euros per person. These amounts do not include the cost of transport to Cameroon and the hunting area, the purchase of a hunting license, slaughter taxes, and the cost of preparing and transporting the trophies, which adds up to several thousand euros. Some of Mayo Oldiri's customers fly by private jet from the USA to Douala, then take another small plane to the southeast, taking advantage of the airstrips of local logging companies.

No doubt these foreign hunters are unaware that the Dissassoue inhabitants and other Baka communities in the region were given no say and no compensation when the Cameroonian state, under pressure from its Western backers, transformed their customary lands into industrial logging units, hunting zones, and national parks. In the early 2000s, dozens of areas devoted to trophy hunting and officially called "zones d'intérêt cynégétique" (ZIC, "zones of hunting interest") were created without their consent, along with three huge parks: Lobéké, Nki, and Boumba Beck.

Limited access to forest resources

ZICs are supposed to act as "safety belts" for park wildlife, says Joseph Bibi, president of Asbabuk. They each cover several tens of thousands of hectares and overlap with logging units. Some are entrusted by the state, in the form of five-year renewable concessions, to licensed hunting companies and guides. Others are managed by local communities (ZIC-GC), who sometimes lease them out to the same private operators. This is the case of the one on the edge of which Dissassoue is located: adjoining the 217,00-hectare Lobéké park, this ZIC-GC n° 1 is leased to Mayo Oldiri by a village committee made up of representatives of the Baka and other local communities, who live mainly from agriculture and small-scale livestock farming.

In all cases, the Baka, whose semi-nomadic culture is often presented as the "first guardians of the forest," find themselves forced to live on the outskirts of parks and ZICs, along the region's dirt roads, with restricted freedom of movement and de facto limited access to forest resources.

Outside the hunting season, they should still be able to circulate in the ZIC to carry out their cultural activities and find sustenance—with a ban on marketing the products and small animals they harvest. A "memorandum of understanding" reiterating this right was signed by the government and the Asbabuk in 2019, then revised and renewed in November 2023.

But as the example of Dissassoue shows, the anti-poaching teams employed by the companies often prevent the Baka from entering the hunting zones. Around 24,000 people have settled in the areas bordering Lobéké Park, and the stories told by one person or another are all the same.

Anti-poaching campaign against customary rights

For example, a group of local residents say it is impossible to enter ZIC n° 30, located to the north of the park, above a certain limit. This zone has been entrusted by the State to Faro Lobéké, a company owned by a French hunting guide, Pierre Guerrini, and the billionaire Benjamin de Rothschild, head of the Edmond de Rothschild Group, until his death in 2021—a dispute has since pitted the Rothschild heirs against Pierre Guerrini over control of the company.

The Baka living nearby, in the Libongo-Aviation area, would like to go fishing in this ZIC, which, according to them, has the best-fished rivers in the area, and harvest yams or wild mangoes. Instead, they are relegated to the role of spectators: Just as they see trucks carrying gigantic tree trunks cut down in the forests they once frequented pass their camp every day, raising huge clouds of red dust that instantly cover the surrounding area, they watch the trophy hunters make their way into these areas now off-limits to them.

The terms "bullying" and "caning" are often used to describe the behavior of certain anti-poaching brigades, made up of ecoguards, locally recruited villagers, and sometimes the military, depending on the period and the area.

Hilaire Beka, a resident of the Mbimbe camp, recounts his brothers' misadventure at the end of 2023: "They had gone into the forest in ZIC n° 2 [which has not had a leaseholder for two years but remains under surveillance, editor's note]. They set up camp for a few days while they harvested djansang, a seed used as a condiment. Ecoguards found them there and beat them up. They've been traumatized ever since."

"We're forced to hide like thieves"

In the community of Ndjo Solo, part of ZIC-GC n° 1, indignation has been rife since Mayo Oldiri installed a barrier with guards, without explanation, at the end of the last hunting season. "This barrier prevents us from carrying out our activities. The women can no longer go fishing. If they manage to get through, the guards who are there search their baskets when they return. They take what they find and keep it for themselves," say several local residents. Contacted by Afrique XXI, Mayo Oldiri did not respond to our questions.

"The Mayo Oldiri anti-poaching officers are constantly threatening us. Even if we don't have a weapon to hunt with and we want to enter the ZIC, they threaten us all year round," testifies Isaac Ngombo, community leader in another locality, Salapoumbé. This is all the more problematic given that "the trees we use to heal ourselves are deep down there."

"We're forced to hide like thieves," laments Olivier Nawe, a resident of a neighboring hamlet. Although members of his community report the problem to various authorities, they are never taken into account, he adds. Even if the Baka, the majority population in the district, are represented on the committees that manage the ZIC-GC, their voice is rarely heard, say those concerned. "There is overwhelming evidence that the commercial interests of safari companies overshadow the use rights of the local population: Safari companies prevent people from practicing subsistence hunting in ZIC-GCs," the Center for Rural Development (SLE), part of Berlin's Humboldt University—along with several NGOs—had already reported in 2019.

In any case, the timing of the hunt itself and its preparations, which begin in February with the tracing of the tracks needed by the hunters, is not good: it coincides with the harvesting season for several fruits and seeds, explains Martin Lembi, Baka community leader in Kika-Jerusalem, a hamlet located to the south of the park, in ZIC-GC no. 3 (84,000 hectares), leased by the local community to a Spanish hunting guide, Pepe Chelet. As of February, the women in charge of harvesting are no longer allowed to enter this ZIC-GC. "If we try to go in, we get a shotgun blast telling us: 'I don't want anyone here, get out,'" says Martin Lembi. Unfortunately, the most productive trees are in this area. The population is therefore forced to cross the Dja, the river that separates Cameroon from the Republic of Congo, to find these seasonal products.

A poor salary

Vulnerable and in a position of permanent survival, some Baka do "small agricultural jobs" for other communities to get by, with extremely low wages: "From 500 to 1,000 FCFA a day" (0.7 to 1.5 euros), confides Jean-Marie Ondja, General Secretary of Asbabuk. Others find themselves reduced to poaching large animals on behalf of powerful sponsors.

According to Assan Gomse, deputy director in charge of wildlife at the French Ministry of Forests and Fauna (Minfof), hunting companies offer a number of social benefits, as they create small local jobs: "In an area as remote as the southeast, this is a significant source of income." By law, hunting guides and companies are required to recruit at least 40-50% of their employees from communities within or adjacent to their area of operation.

But most of the jobs on offer are seasonal and poorly paid. Even after twenty years' service, a Mayo Oldiri camp guard hired on a year-round basis can't earn more than 50,000 FCFA a month (76 euros), says a former employee. A tracker is paid between 90,000 and 120,000 CFA francs a month by the same operator, according to him (in Cameroon, the minimum wage in the private sector is 60,000 CFA francs, or 91 euros). It's always the Baka, who know the forest best, who are enlisted to do the job of spotting and tracking animals, before blocking them, with dogs for certain species such as the bongo, to leave them at the mercy of the hunters. Some trackers say they appreciate their pay, but are aware that it is derisory in view of the dangers involved and what the foreign hunting guide receives on his side.

What's more, jobs are few and far between. While for a few weeks the companies employ dozens of people to prepare the trails, during the four months of hunting they only need 26 people (drivers, mechanics, waiters, maintenance staff, cooks, trackers, guards, etc.) for each of their camps, i.e. one or two per ZIC—a camp receiving two customers per month.

"No real benefit"

Michel Zabotoum, Baka chief of Zega, a hamlet close to the border with the Republic of Congo and located in ZIC-GC n° 3, regrets that no member of his community works for Pepe Chelet—whose customers are mostly Russian. "If at least young people from here were recruited, it would be all right," sighs this patriarch. He also explains that, while the people of Zega have been able to enter the ZIC-GC for some years now and carry out their subsistence hunting within a certain perimeter without being disturbed by the eco-guards, they do not benefit from the meat of the animals slaughtered by the trophy hunters, which should normally be shared equitably between the communities. "We don't receive any benefit" from trophy hunting, he concludes.

Assan Gomse points out that sport hunting generates financial spin-offs for the local and national economy. The sums paid by private operators are welcome, confirms Baudouin Gath-Attasso, who chairs the village committee managing ZIC-GC n° 3, located south of the Lobéké park. Each year, his committee collects 8.4 million FCFA in leasing fees (i.e. 100 FCFA per hectare), paid by its tenant, Pepe Chelet, and its share of slaughter taxes (for each animal killed, the hunter must pay a price according to a pre-established scale), i.e. 600,000 FCFA in 2022.

Baudouin Gath-Attasso explains that this income is used to finance the construction of community structures, the salaries of a few teachers, and anti-poaching activities. "The money is used to protect the area and do a bit of social work for the Baka communities," he sums up, noting however the difficulty of managing this income, due to a lack of training for committee members.

But for Pepito Meka Makaena, president of the village committee administering ZIC-GC no. 1 leased to Mayo Oldiri (which welcomes eight customers per season), the benefits that communities derive from trophy hunting "are very small compared with the constraints imposed on them." His committee, which represents 18,000 people, receives around 7 million FCFA a year from Mayo Oldiri, including 5.4 million in lease taxes. "The price per hectare, 100 FCFA, was negotiated when people were still naïve," he observes. "That's not even 500 FCFA a year per person, and the population is growing as time goes by. At the same time, this same population is forbidden to enter the area to look for food. We're punishing them for nothing." He's done the math: If local people could harvest non-timber forest products in the ZIC-GC, some of which could be sold, it would bring in several hundred million CFA francs.

3,800 euros to kill an elephant

On a national level, Cameroon earns little from trophy hunting, which is practiced on almost 12% of its territory (in the north, center, south, and southeast), generating between 800 million and 1.2 billion FCFA per year. These sums come mainly from the leasing taxes paid by hunting companies for ZIC—between 50 and 170 FCFA per hectare—and slaughter taxes for ZIC and ZIC-GC. In 2019, the country received 385 hunters and collected 835 million FCFA in 2019. The 2022-2023 hunting season, for its part, brought in around 800 million FCFA, including 250 million in leasing taxes, according to Minfof. Slaughter taxes, which had remained unchanged for thirty years, have just been revised upwards. From now on, a foreigner will have to pay 3,800 euros to kill an elephant or a bongo.

Is it in line with the expenses and profits made by guides and companies? The government doesn't know, as it has no control over their income—customers pay into foreign accounts.

Nevertheless, sport hunting remains a useful conservation tool from Minfof's point of view:

"We are wildlife managers. Our primary mission is to protect and conserve Cameroon's wildlife diversity to ensure its sustainability," comments Assan Gomse. "The state lacks sufficient resources to effectively monitor animal populations in Cameroon's extensive network of protected areas. In these conditions, professional hunting guides are important players in the preservation of wildlife in areas of hunting interest, over and above the exploitation aspect, as they are responsible for their management. Trophy hunting, as it is practiced, with strict rules—prohibition on the killing of females and juvenile animals, removal of adult males, etc.—and quotas determined by the local authorities. On the contrary: It helps to regulate them."

However, an inventory carried out by WWF and Minfof revealed that the number of individuals of certain species had declined between 2015 and 2018 in some ZIC and ZIC-GC in the region. "The increase in poaching pressure and especially sport hunting in ZIC and ZIC-GC has affected bongo populations. In fact, bongo is one of the main targets of sport hunting in the area, and the annual quotas for killing this species, allocated by the forestry administration, are generally not drawn up on a scientific basis that guarantees the species' sustainability," says the study. The situation is similar for buffalo, also highly prized by trophy hunters.

A very old pattern

Few economic opportunities, social problems: Cameroon is no exception. According to the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), big game hunting only finances a small proportion of the amounts needed for conservation, and its socio-economic benefits are low.

Why should we be surprised? "Hunting areas were originally created for recreation. The current justification of their existence by the need for protection marks, at best, an evolution in the purpose of these areas," points out Samuel Nguiffo, General Secretary of the Centre pour l'environnement et le développement (CED, Center for the environment and development), an NGO based in Yaoundé. "These areas are part of a type of extractive management, of a very old scheme, which was not originally built to defend the interests of the local population, but which we are now trying to adapt to the strategies of sustainable development and climate change."

This legal expert points out that industrial logging, sport hunting, protected areas, and, more recently, the development of mining are always to the detriment of local populations. Compared to commercial interests, community use rights are less well protected.

To try to improve the situation, Asbabuk plans to raise awareness among hunting companies of the need to respect the Baka's right to enter the ZICs and national parks they surround. "Safaris need to make their employees aware, to make them understand that they have to let the populations look for food. We have signed a Memorandum of Understanding that allows people to go into the forest freely to carry out their traditional and subsistence activities. This must be respected," insists Honoré Ndjinawé.

Shifting the paradigm?

However, this will not erase the injustice of the system: "People from elsewhere can, because they have the financial means, kill animals, whereas if the local population is found with the same species, they are arrested and condemned. It hurts," says a local conservationist, speaking on condition of anonymity. According to him, "no good control or monitoring is really done during the activities of these big, white poacher hunters."

In a letter of support for a bill to ban the import and export of endangered species trophies in France, the IUCN French Committee also takes a stand against this type of hunting, which "conveys a model of social inequality between wealthy hunters who pay to kill animals and poor local populations whose rights or uses of nature may be restricted."

The tragedy and irony of the situation is particularly striking for trackers who help strangers kill animals that they themselves have no right to hunt, even for subsistence. "We should be able to rely more on the local population to safeguard the forests and wildlife, which they know better than anyone else and have always been able to protect." As for Pepito Meka Makaena, he would like to see ZIC-GC n° 1 transformed into a national park, which would put an end to sport hunting and remove some of the obstacles to movement. "The forest must remain freely accessible. We can organize the fight against poaching and imagine another type of protection that doesn't put the population in difficulty," he asserts.

- View this story on Mediapart