As the second largest forest country in the Congo Basin, Cameroon has been steadfast in its efforts to combat illegal logging through international, regional, and national agreements. However, there has been a troubling increase in illegal logging cases, with legal logging companies found to be the culprits. To uphold Cameroon’s commitment to protecting its precious forests and the environment, all these stakeholders must work together.

"Looted Forests" (1/4).

This is a series of 4 collaborative investigations produced & co-published by Le Monde and InfoCongo, in partnership with the Pulitzer Center’s Rainforest Investigations Network.

During a 12-month investigation, journalists from both media met with a dozen loggers in Cameroon’s rainforest. Their testimonies and official documents show that corruption speeds up illegal logging in Cameroon, to the detriment of indigenous forest communities protecting these forests for centuries.

*Names have been changed to protect sources who said they feared reprisals from the authorities.

“The only person who doesn’t know about it is the state”, because they think the wood comes from a legal logging area, says Guillaume*, who preferred not to be identified in the story. The man we met in November 2022 is a well-known logger “without legal documents” from the South region of Cameroon. To tell his story, like the other traffickers interviewed, he moved far from his stronghold, several kilometers away. To carry out their activities, several legal companies work with these traffickers, such as Guillaume. Their main activity? Wood laundering: making logs of illegal origin, legal.

Guillaume, a 53-year-old man, started in 1998, working in a logging site in the East, the region with the most forest cover in Cameroon. At the time, Guillaume, who had lost his father, was living with his uncle, the mayor of the locality. The mayor recommended his nephew to one of the largest logging companies in the country, which is still in operation today. Guillaume travels through the forests, observing and learning from other employees of the logging company. He noticed that “a lot of mafia” reigned in this sector. After several years of working for multiple companies, he returned to his native South region and started his own business. Today, he leads a network made up of a host of logging companies, all of whom, like him, operate clandestinely. They have neither documents nor approvals from Cameroon’s Ministry of Forestry and Wildlife (MINFOF).

According to Guillaume, laundering is done at all levels. From identifying species in the forest to cutting trees, illegal wood is laundered and inserted into the legal circuit. A well-oiled trade from villagers to exporters through logging companies, sawmills, and government officials. Once in the port of Douala or Kribi, the country’s two ports, this wood is exported to the international market.

As a nonprofit journalism organization, we depend on your support to fund journalism covering underreported issues around the world. Donate any amount today to become a Pulitzer Center Champion and receive exclusive benefits!

Cutting timber beyond the limits

Traffickers like Guillaume work in partnership with legal companies that have obtained authorization to exploit small forest plots in their locality or elsewhere. From 2013 to 2022, Cameroon’s Ministry of Forestry allocated at least 548 small logging titles, better known as Vente de Coupe (vc) in French. These are permits granted to logging companies to exploit timber in areas not exceeding 2,500 hectares and have a one-year exploitation period, renewable up to two times. However, over the years, several of these companies have been sanctioned for illegal logging, including cutting timber beyond the limits of the area assigned to them.

According to official reports from the Ministry of Forestry and Wildlife (MINFOF), some companies, although they have a specific plot of land to exploit, cut timber beyond the limits set in their specifications. Others buy species from local people, usually outside the boundaries of the area they are authorized to log.

InfoCongo and Le Monde analyzed six editions of the “sommier des infractions” (MINFOF’s quarterly documents listing companies and individuals sanctioned for forest law violations), published between 2015 and 2021. The results of these analyses show that many off-limit logging cases are listed in the Ventes de Coupe. When these companies are caught, sanctions range from fines to formal notices and even temporary suspension of their forestry license. However, MINFOF continues to allocate plots of land for logging to these multi-recidivist companies, thus helping to satisfy the strong Asian demand for tropical logs.

Formerly exported mostly to Europe, Cameroonian wood has changed its destination. “Europe has begun to tighten its policy and as a result, companies that sell on the European market will have to justify the source of the wood”, said Justin Kamga, coordinator of Forêts et Développement Rural (FODER). This civil society organization specializes in monitoring alleged illegal logging activities. Exporters have therefore turned to Asian countries, which, according to him, “are flexible in terms of compliance with regulations.”

These 5 countries have the highest value of wood imported from Cameroon in 2021.

Thus, Asia has become Cameroonian timber’s main destination, as official export data show. In 2019 alone, Vietnam and China accounted for 70 percent of the total volume of timber exported from Cameroon to foreign countries, according to an analysis of data from Cameroon’s forestry revenue security program. These figures match with the figures from the United Nations database on world imports and exports (UN Comtrade). Also on the ground, several timber traffickers confide that their partners are primarily Asian.

Destroyed forests

During a 12-month investigation, InfoCongo and Le Monde met with a dozen loggers who, like Guillaume, are experienced in illegal timber trafficking, with communities living in the heart of Cameroon’s forests and with prospectors who help illegal loggers identify timber in the forest. This field information was cross-referenced with official data related to annual logging permits in Cameroon from 2013 to 2022, data from the “sommier des infractions” (a database of perpetrators of forest law infractions sanctioned by MINFOF), and data from the National Anti-Corruption Commission (CONAC) related to violations in the forestry sector.

According to the Cameroon Forest Atlas, from 2013 to 2022, the 548 timber sales granted covered 943 thousand hectares of forest in Cameroon, which is more than twice the area of Cape Verde. Analysis of this data shows an increase in the number of timber sales granted over the past ten years. These results shock experts for whom these titles “are not necessarily supposed to be titles for sustainable management,” laments Paolo Cerutti, an expert at the Center for International Forestry Research (CIFOR), a non-profit scientific research organization. According to the Environmental Investigations Agency (EIA), “timber sales do not require any management plan. The area allocated by timber sales is entirely open to exploitation”. This causes many violations. “Many companies use the title just to launder timber from other areas,” says Achille Wankeu.

According to the forestry analyst of the Centre pour l’environnement et le Développement (CED), it is then “less expensive” for these companies “to go and exploit where there are fewer constraints,” which makes it difficult to trace the wood. This is “a fairly widespread phenomenon”, says the expert, who sums up the situation as follows: “an operator is given permission to cut everything for three years.” And this is felt on the forest cover.

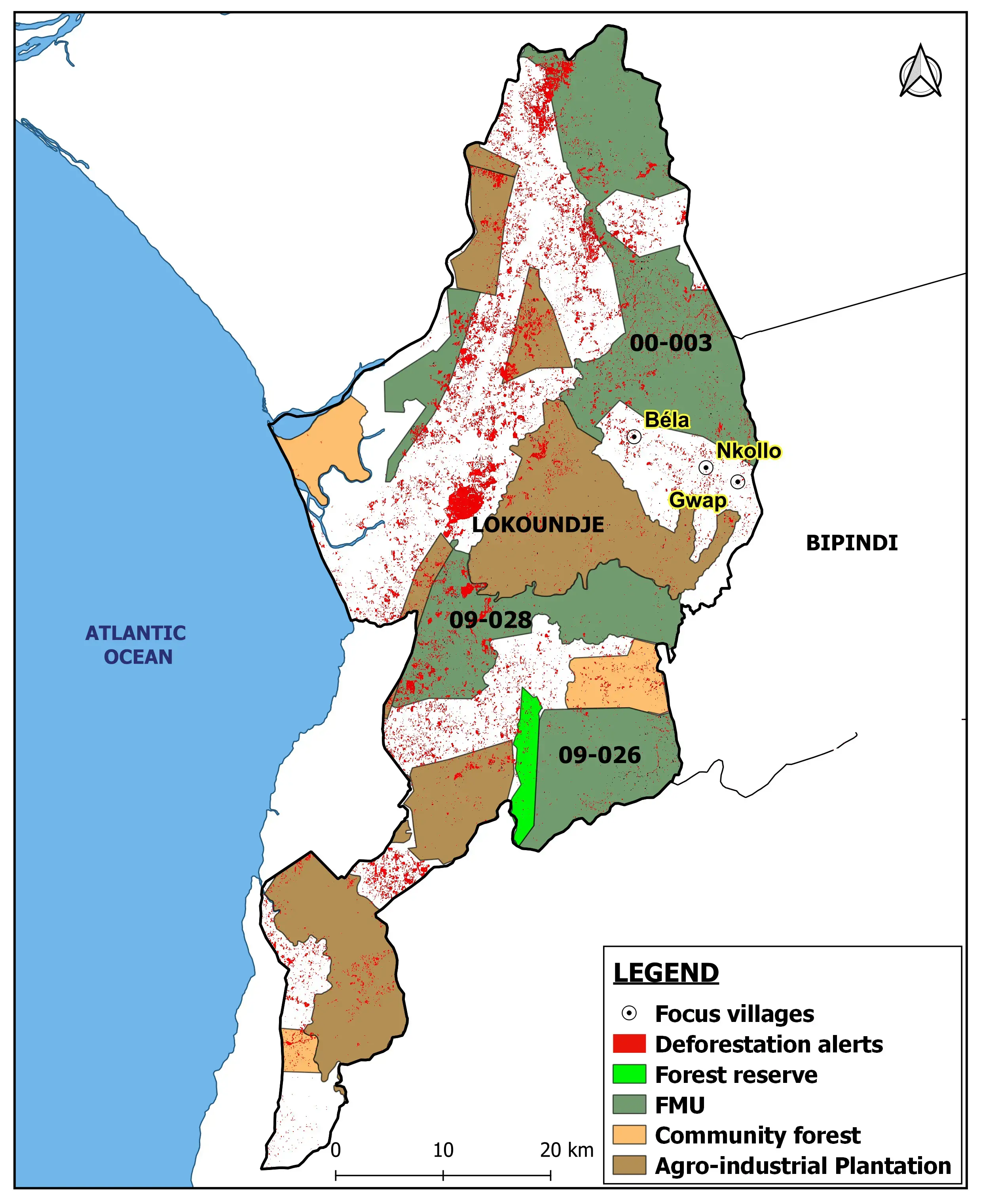

According to Global Forest Watch, from 2013 to 2021, Cameroon lost 1 million 260 thousand hectares of forest cover, which is greater than the size of Gambia and São Tomé and Príncipe put together. The Center, East, and South regions of Cameroon are the three main deforestation hotspots for the past ten years. The South region records the largest number of logging sales, accounting for 40 percent of the logging sales allocated in the last ten years.

Search for species “everywhere”

“We lose the forests. We also lose our well-being. The forest purifies the atmosphere, creates a microclimate, and remains a refuge for animals,” says civil society leader Justin Kamga. The Bagyeli, indigenous forest populations living from fishing, hunting, and gathering, are the most impacted by this environmental destruction. These men and women, who have lived in the heart of the forests of the Congo Basin for centuries, are now struggling to find enough to eat. As a result, many men in the community are joining forces with illegal traffickers and logging companies. With their good mastery of the forest, they are recruited as prospectors to identify the most prized wood species by buyers or even those prohibited.

It all starts in remote forest villages where people often struggle to make ends meet. Some legal companies then have several approaches, according to testimonies collected. First, there are the young Bagyeli, indigenous populations, commonly called pygmies, recruited as “prospectors”. They are responsible for identifying wood species that no longer hold any secrets for these original forest dwellers who live by fishing, hunting, and gathering.

These men, often young, have the job of crisscrossing the bush in search of Padouk, Tali, ekop-beli… and even endangered species listed in the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES), such as Autranella Congolensis. According to at least five prospectors interviewed, many companies then commission them to search for species “everywhere,” including beyond their limits, says Emile*, a prospector for five years. Like the others, the 38-year-old Bagyeli man receives a specific list of species to identify.

From morning to night, these Bagyeli crisscross the forests, identifying trees, placing marks, and looking for roads that will later allow the teams to move with their equipment and the trucks to transport the logs. At the end, once the wood is loaded, some are paid with bags of whiskey, a popular drink among this population. Others will either receive a sum of money well below the amount set or won’t receive anything at all. When he returns each evening, Emile receives 2,000 CFA francs for his salary. For Mathias, they started by giving him 10,000 CFA francs per week and then nothing. “When the site manager is there, he makes false promises. You hear that a prospector should normally have more than 100,000 CFA francs per month or more. When you hear the figure, you know that in the hunt, you can never have such an amount. It’s easy for you to get into this business”, regrets this young leader.

If the prospectors, essential in the chain of illegality, do not make a profit from their long days in the forest, some traffickers find their account. This is the case for Guillaume and Jonathan*. The latter started logging 27 years ago. In a village in southern Cameroon, his small team is made up of sawyers, porters, transporters. Over the years, the expertise of this sixty-year-old man has attracted companies that even go so far as to sign subcontracts with him, the illegal operator, “without papers”, as he claims.

“You find a company that has at least two, three, five sales of timber in different villages, different departments. It cannot be at the same time in the East, in the South,” emphasizes Jonathan, who thus becomes the “relay” of these legal companies, holders of cutting sales granted by the MINFOF. The “suspicious” man demands fixed-term contracts, the time of the work. Some of these agreements include “prospecting, felling, and bucking”, he proudly states.

Fighting illegality

With his team, they identify the species according to the company’s requirements and cut them into logs. All this, “without respecting the area delimited” in the specifications or even “the rules of exploitation,” of which they know nothing, admits Jonathan. Guillaume confirms this.

In 2022, however, Jules Doret Ndongo, the Minister of Forests and Wildlife, insisted in a press release on “the government’s unwavering commitment and determination to continue the fight against all forms of illegal exploitation of forest and wildlife resources throughout the national territory.” This official communication came the day after the death of a forestry officer killed during “an altercation with a gang of illegal loggers, armed with bladed weapons and hunting rifles”.

A year earlier, in an administrative letter addressed to the regional delegates (his representatives in the ten regions of the country), the Minister denounced complicity between officials of his administration and traffickers. Jules Doret Ndongo recalled that this “phenomenon not only contributes to the loss of our forest and wildlife resources but also constitutes a significant loss of revenue for the state coffers. According to a report by the National Agency for Financial Investigation published in 2021, illegal logging and wildlife exploitation result in a loss of revenue of about 33 billion CFA francs each year to the State of Cameroon.

Negotiating with residents

Apart from the traffickers, even local people keen on this juicy business approach the companies to bargain for a tree in their fields. “When you know you have your wood, you go to them” (to the company), says Steve, a native of Mounguè.

In this locality, many inhabitants confide that they have sold various species to Amougou Amougou Jules (AAJ), a company managing a logging sale in the locality. From 2013 to 2022, this company has obtained five (05) sales of cuttings, respectively in the South, Central, and Littoral regions. On his smartphone, Steve scrolls through numerous photos. We see men loading a truck with logs. Some are marking the wood. According to this leader, who discreetly took these photos and knows all the employees and bosses, the company is “constantly” buying wood from the locals. His uncle has just sold several feet of Pachi for nearly 250,000 CFA francs, a real fortune.

“Negotiating with the population is cheaper because they don’t know the price per cubic meter. They (company managers) buy the Tali, Doussie, Pachi,” says Steve, who points to the inhabitants’ poverty. However, the law prohibits exploitation beyond the limits and purchases from local residents. “The tree does not belong to the farmers, even on your customary land. This means that the fact that people sell trees is a form of illegality,” says Raphaël Tsanga, a lawyer and expert at CIFOR.

When asked, AAJ brushes off the accusations. “Your claims are haphazard, slanderous,” the company replies on the WhatsApp messaging app. “Our company works in accordance with forestry regulations and will not let ill-intentioned individuals tarnish the image of my company,” the message concludes. Yet, AAJ is convicted of logging beyond the limits in the notebook of infractions by the Ministry of Forestry. And this is not an isolated case.

Insufficient Sanctions

By comparing the data on stumpage sales with the data in the infractions register, we noted that four of the sanctioned companies are among those that benefit from the greatest number of stumpage sales allocations. These are:

- Société Commerciale Industrielle et Forestière (SCIFO);

- Huguette Forestière;

- Société Bois Africains du Cameroun (SBAC); and

- Agence Forestière Camerounaise (AFC).

From 2013 to 2022, these four companies obtained 59 timber sales covering more than 80 thousand hectares of forest. According to a 2019 WWF report, three of these four companies (Huguette Forestière, SBAC, AFC) have signed partnerships with Asians to exploit their timber sales. Numerous logging companies that have worked in the localities visited, such as Agence Forestière du Cameroun (AFC), Huguette Forestière, and Feemam are mentioned in the report and condemned for logging beyond the limits. In its 2019 report, CONAC pins the Société Africaine des Bois de l’Est (SABE), a company familiar to the inhabitants met, for “exploitation beyond the limits of the sale of cutting and fraudulent use of marks.”

InfoCongo and Le Monde note that the same companies appear in several editions of the six summaries analyzed. In some cases, they are accused of new cases of illegal logging. In other cases, the infractions they committed in previous years are mentioned again, due to the lack of payment of the fine imposed by the Ministry of Forestry. These facts show “a poor follow-up of the cases that are opened”, denounces the coordinator of FODER. “Magistrates should, in principle, take up these cases to pursue these companies. Even if these companies are bankrupt and the business is closed, the people responsible should be prosecuted until they are able to pay these taxes,” insists Justin Kamga.

At the Environmental Investigations Agency, Benoît Dameu is offended that these companies are still in business. “These companies were simply suspended or forced to pay some lump sum fines. But this has not allowed them to have their logging permits withdrawn altogether,” he laments. Condemnations that have been denounced for years do not seem to curb illegality.

Controlling the Asian market

To stop this trafficking, the government has put in place structures and other mechanisms. For example, in early 2022, the country officially launched the second generation of the Forest Information Management System (SIGIF2). This software tool aims to trace timber from the forest to the port. This tool was designed under the Voluntary Partnership Agreement (VPA/FLEGT) between Cameroon and the European Union (EU).

But the EU did not receive it when it was put in place. “The version of SIGIF2 presented is not the instrument expected under the FLEGT VPA. Therefore, the certificates issued by SIGIF2 cannot be recognized or validated under the European Union Timber Regulation (EUTR),” explained the EU and the German Cooperation in a statement in 2021. They added that they had “openly expressed their differences throughout the development and evaluation process of SIGIF2, while offering their material, financial and technical support to eliminate these discrepancies.”

For Cameroonian civil society experts, SIGIF is struggling to stop illegal logging. “The inefficiency of the SIGIF2 information system has allowed many illegal practices to develop,” says Benoît. In 2020, an EIA report revealed connections between logging sales holders and Asian sawmills located in Yaoundé and Douala. Three years later, Benoît Dameu says the practice continues and has even become “more sophisticated.” The case of the Vietnamese, at the time we published the report, they were mostly installed in Douala and Yaoundé. Now they are in the interior of the regions. They are in areas like Nanga Eboko. They are also in the eastern zone.

In this context, other leaders point to the responsibility of the European Union and call on it to better control the Asian market. “You (EU) don’t want illegal wood on your market, we encourage you. We realize that you (EU) consume these products illegally exploited in our country and that are laundered and pass through the Asian market,” said Justin Kamga. And this trend is likely to continue. For large sums of money are at stake. According to the United Nations database on world imports and exports (UN Comtrade), there is a huge gap between the value of exports and imports of wood between Cameroon and the two main Asian countries that consume Cameroonian wood.

Analysis of this data shows that from 2013 to 2018, China reported importing timber valued at $1.497 billion from Cameroon while Cameroon reported exporting timber worth $693 million to China. Thus, there is a gap of $693 million less on the declarations made by Cameroon. In the same period, Vietnam declared that it imported wood worth $883 million from Cameroon, compared to $476 million in exports declared by Cameroon, a gap of $406 million less on the Cameroon side.

Despite these losses, trucks full of logs continue to travel the forest roads. “Logging is like drugs. It’s an exercise. At any time you want to exercise,” concludes Guillaume, the illegal logger.