Read the Spanish version of this story.

MATAMOROS, MEXICO—The improvised campsite just steps from the U.S.-Mexico border holds about a dozen tents and 150 people, including a dozen children and two pregnant women.

Central Americans, Haitians, Cubans and Venezuelans vie for a shady spot under two trees at a small park in the city of Matamoros on the Mexican side of the border. They eat thanks to the charity of churches and other aid organizations. They bathe and wash their clothes in the Rio Grande, which separates the two nations. They also use the river as an alternative to the five portable toilets in the park.

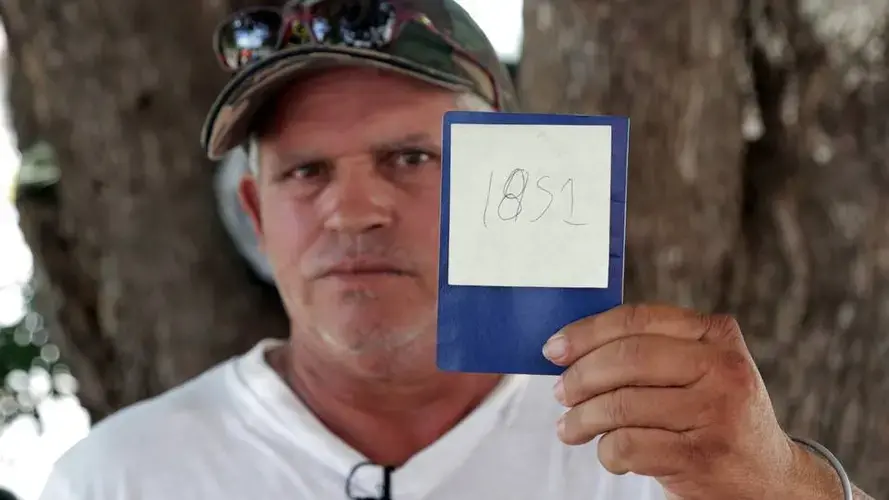

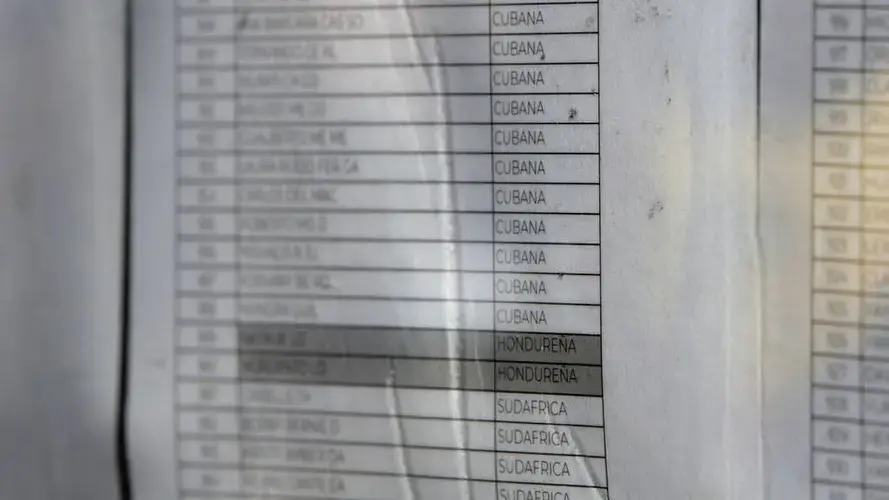

Long lists of papers taped to window panes hold the names of thousands of migrants waiting their turn to ask for U.S. asylum. The largest number of asylum seekers by far are Cubans, followed by Venezuelans and Nicaraguans. Many Central Americans believe they don’t have a good chance of winning asylum and prefer to try to swim across the river.

There are now some 40,000 migrants waiting their turn along the border, according to various news reports. Mexico’s National Immigration Institute told el Nuevo Herald that 20,000 immigrants have been returned from the United States since June, when it signed the Migrant Protection Protocols accord with Mexico.

The agreement came after President Donald Trump threatened to impose tariffs on all Mexican products. It requires migrants from Latin America seeking U.S. asylum to wait on the Mexican side of the border until their cases are decided by U.S. immigration officials. Since the implementation of the agreement, the arrests of undocumented immigrants on the border with Mexico have decreased by about 45 percent, authorities said.

“We planned to ask for asylum at the border and argue our case once in the United States. We knew that the wet foot, dry foot policy did not exist any more, but the Cuban Adjustment Act still protects us,” said Yailín, a Cuban migrant. The 1966 law is a Cold War relic that allows Cubans to obtain permanent residence, or green card, after being in the United States legally for at least one year.

After Yailín was returned to Mexico at 4 a.m. across the desolate Gateway International Bridge that links Matamoros and Brownsville in Texas, she could hardly believe what she had gone through over the previous three months while trying to reach the border: two journeys across Central American jungles; a repatriation to Cuba; persecution by the island’s political police; a kidnapping and ransom in the Mexican border town of Reynosa; an illegal crossing of the Rio Grande; and finally her deportation from the United States back to Mexico.

“I thought I would have a panic attack. I had never been in Matamoros. I didn’t know what was going on with my husband, my brother, his wife and my neighbors, who were detained. I called my other brother, who was waiting for news in the United States, to tell him what was happening and then another migrant gave me a blanket. I’ve been here since,” she said, standing a few steps from the border bridge.

Like many of the others waiting on the border, she does not want to be identified and gave only a pseudonym. An immigration lawyer told her that speaking to the news media could jeopardize her asylum case. But she’s also afraid.

Matamoros is just an hour’s drive from Reynosa, where a priest was recently kidnapped for not allowing criminals to haul away a group of Cuban migrants to be held for ransom and seek payment from relatives in the United States.

Although President Donald Trump has toughened U.S. policies on Cuba and returned bilateral relations to a point before the thaw launched by his predecessor, President Barack Obama, Cubans fleeing the island do not have the benefits they once enjoyed.

The White House has tightened restrictions on travel to Cuba, allowed lawsuits in U.S. courts against anyone that profits from Cuban properties seized by the Castro government and slapped sanctions on cargo ships that deliver Venezuelan oil to the island.

Many Cubans now fear the return of the Special Period, the crisis that Cuba suffered in the early 1990s after the end of Soviet subsidies, and that has spurred many to flee.

Yailín’s group left the island for Nicaragua, which has eased its visa requirements for Cuban visitors. They crossed Central America and reached Mexico, but were then detained and deported to Cuba, without their identity documents or belongings. They obtained new passports one month later and started a new journey, this time from Panama, another key jumping-off point for thousands of Cubans.

The situation on the island is unbearable, Yailín and others that accompanied her on the journey said. They complain about repression from Cuban security agents and the economic crisis, which has turned sharper with the collapse of Venezuela’s economy and cutbacks in its oil shipments to the island.

Obama’s decision to end the “wet foot, dry foot” policy in early 2017 meant that Cubans no longer have automatic refuge in the United States, but they can still apply for asylum to enter legally. Since September of 2018, more than 16,000 have been detained as they tried to cross the Rio Grande illegally or applied for asylum at border crossings — more than twice the number from the previous one-year period. The number of Cubans deported by the U.S. government to the island also rose, from 160 in the first year of the Trump administration to 560 this year.

Gladys Edil Cañas is a Mexican activist helping migrants who have been deported or have no money. She goes to the Gateway International Bridge every day to deliver humanitarian aid donated by Matamoros residents.

“The human rights lady is coming,” some of the migrants shouted when they saw her recently. In just a few minutes the mob surrounded her and dozens of hands reached out for the blankets, food and water she carried.

“This crisis started some months back, and turned worse with the activation of the recent agreement between Mexico and the United States” Edil Cañas said. “That’s how they started to settle here.”

Matamoros, which sits directly across Brownsville, Texas, is the second largest city and one of the most violent in the Mexican state of Tamaulipas, with more than 50 murders per month in the state according to official reports, as well as many cases of kidnappings-for-ransom, especially of migrants.

The number of detentions along the southern U.S. border spiked in recent months and established historical records. In May alone, 144,278 people were detained, more than double the number in the previous May. The tendency continued in June with 104,344 migrants detained, many of them in family groups or unaccompanied minors.

Edil Cañas believes the Mexican government is not prepared to assume the burden of the Migrant Protection Protocols.

“The weight of this crisis is falling on civil society. The government is not helping at all. It does not provide food or healthcare or education for the children and women who are living on the streets,” she said.

“Some of these people fear for their safety, and that’s why they don’t go far from the bridge, which is federal (Mexican) territory and is guarded by the Marines, the National Guard and the Grupo Beta from Immigration,” Edil Cañas said.

Mirtha, 49, a neighbor of Yailín in the province of Camagüey in eastern Cuba, has accompanied her group during the two attempts to reach the United States. Her daughter, who lives in Miami, paid for the travel and stay in Mexico. With the shutdown of consular services at the U.S. embassy in Havana, leaving legally for the United States or applying for asylum from the island is “practically impossible,” she said.

For many, reaching the border has been a terrifying experience.

“I would prefer to drown in the river than by a gunshot in Reynosa. Cubans are not accustomed to the violence here,” Mirtha said of her experience crossing the Rio Bravo. After waiting at dawn amid bushes on the Mexican side of the river, the smugglers who charged $100 per person loaded them on rafts and ferried them to the other side of the shore as the first light of the day illuminated the scene.

A few days earlier, the group had been kidnapped and held for ransom: “We were stopped by two trucks. They separated the men and the women and took us to a house where they smoked marijuana and drank. They demanded $5,000 and the contact numbers for our relatives in the United States,” she said.

After a long negotiation they handed over the $3,000 they were carrying and another $1,000 they had hidden in a hotel. Without money and afraid of another kidnapping, they settled on crossing the river to escape the violence.

“While I was detained on the U.S. side, my daughter got a call from Mexico. A woman was crying, claiming she was me, and the alleged kidnappers demanded $10,000. My daughter, who just had a baby, almost went crazy trying to figure out how to get the money to save me,” Mirtha recalled.

The Cuban migrants don’t want to even hear about the possibility of leaving the area near the Gateway International Bridge in Matamoros to look for work. “We’re afraid that we’ll be attacked again. We also don’t know if working in Mexico could affect our asylum case in the United States,” Mirtha said.

Her appointment to appear before a U.S. immigration court judge is scheduled for late September.

“We’ll be here until then. Without a roof, a bathroom or food,” Mirtha said. “But at least we’re safe.”