India is the first country to have corporate social responsibility (CSR) legislation, mandating that companies give 2% of their net profits to charitable causes.

Innovative? Perhaps on a policy level. But some small-medium size enterprises within India have already embedded social impact into their company ethos.

The new CSR law is a massive 294-page act that requires companies to set up a CSR board committee, allocate 2% of net profits in the last three years to CSR, and be reviewed at the end of each financial year by the board's director to ensure compliance. Beyond that, enforcement is a bit vague.

The law applies to the following companies registered in India: those with net worth of 5 billion Rs. (approximately $80 million); turnover of 10 billion Rs. at least ($160 million); or net profit that exceeds 50 million Rs. ($830,000). According to the Economic Times, about 8,000 Indian companies meet this definition, which would equate to 12,000 -15,000 crore Rs. annually in giving (or nearly $2 billion).

The corporate giants such as Wipro, Reliance, Tata, Airtel already have foundations and partake in philanthropic activities aimed at poverty reduction. But critics say that philanthropic funding is not always the smartest way to tackle India's serious social issues.

In 2008, Bill Gates spoke at the World Economic Forum about "creative capitalism." He encouraged companies to identify their expertise — be it technology, agriculture, healthcare — and develop products that could "stretch the market forces." A slightly more nuanced take on "doing good," it meant honing in on the business' specialty, not just throwing money at various charities.

Can that be applied to India's new CSR law? Is it merely about giving or does the kind of giving matter?

ZMQ Technologies is medium-sized company housed in Manesar, a community on the fringes of India's new tech city, Gurgaon. Founded by two brothers, Subhi and Hilmi Quraishi, ZMQ produces commercial software for schools, corporations, universities, and more. Since inception in September 1998, the Quraishi brothers have been allocating 12% of their profits to tech tools. Hilmi is keen to point out that they produce tech tools for development rather than donate directly to development organizations. Why?

"Imagine if we donated 12% in cash to a charity. It would just be a drop in the ocean," Subhi says. "This makes more of an impact."

The numbers indicate that as well.

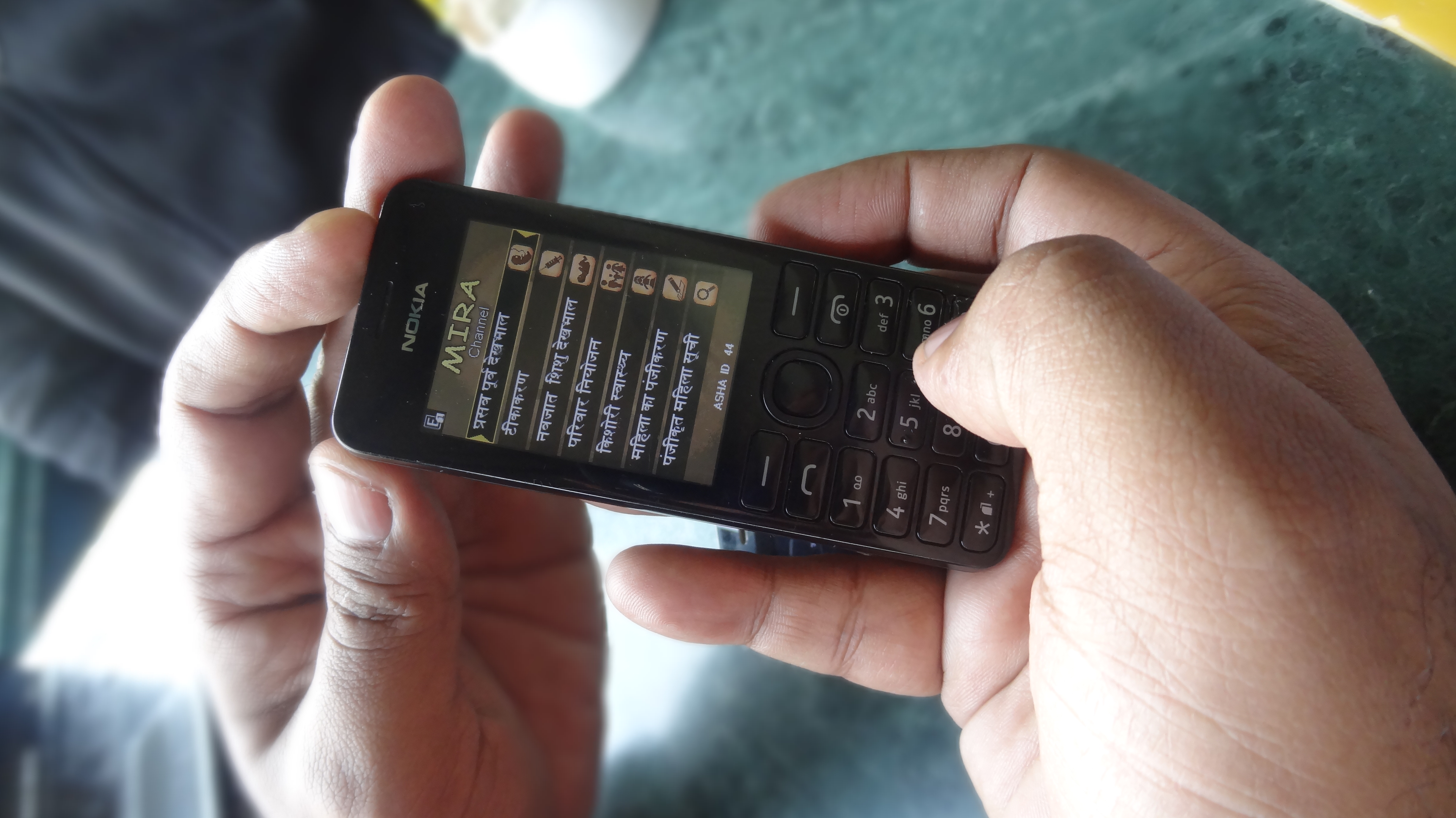

In 2005, ZMQ debuted with one of their most widely-reached "tech for good" products. In 2004, India had been diagnosed with a HIV/ AIDS pandemic; at the time, about 5.13 million Indians were defined as persons living with HIV/AIDS. Working in technology, the Quraishis were intrigued by the popularity of mobile phones and more so, games played on them.

"In smaller towns in India, there was limited access to media. The games could be the vehicle to spread information," Subhi says.

They crafted four mobile games on HIV/AIDS for World AIDS Day 2005. In partnership with telecomm operator Reliance, the games reached 29 million subscribers that year. Those numbers escalated to 42 million subscribers in subsequent years. And 10.3 million game sessions were downloaded.

One of the games tapped into India's favorite pastime, cricket. In the game "Safety Cricket," the task was to score runs and collect safety symbols – condoms, HIV information, AIDS red ribbons, and even, a faithful partner — while protecting yourself from unsafe sex, infected blood transfusions, and infected syringes.

In December 2006, the games spread from India to East Africa, becoming available in Kenya, Tanzania, and Uganda. In the past 8 years, the company has developed 120 games on social and health issues. They refer to them as forms of "edutainment."

"Corporates can be agents of transformation. We're trying to do that," Subhi says.

In 2006, they got a call from DC-based Ashoka, an organization that promotes social entrepreneurs, nominating them as fellows. "What is social enterprise?" they asked the Ashoka team. While the Quraishis had already been dabbling in the space, they were unaware that it had a category or name. For them, it was simply the way to operate.

"To us, this is just a more sustainable process for change. We have to create markets and opportunities for these tools to keep them going. NGOs can only operate for as long as they have funding. That's not really sustainable," Hilmi says.

ZMQ's most recent project, Freedom Polio, is a one of the largest mHealth programs designed for rural health workers to track immunizations in the field. It's selling point, they say, is that it produces live data: which households have been inoculated, which are missing. And the data is automatically analyzed producing a colored map, indicating trouble spots or gaps.

Doing work at the grassroots level, Hilmi says, has exposed them to issues that they were unaware of previously. For instance, Freedom Polio launched in Meerut, a city neighboring Delhi, with 1,300 health workers using the mobile tool. Data revealed that pockets of children were being missed; upon closer inspection, it became apparent that many of these children had mental health problems.

"We don't live in a country where mental health is a top priority," Subhi says.

Rather than just pass on the data to a health organization, the Quraishi brothers went looking for a non-profit focused on mental health to collaborate with. They came across Sangath, a Goa-based organization with nearly 30 years of experience. Now, the two, ZMQ and Sangath, are creating mobile-based tools for parents of children with mental health conditions.

The brothers say that their foray into health issues has shown them that healthcare management tools are largely top-down. "That's not the way to do it, though," says Hilmi. "We want to explain to people why they should take certain medicines, not tell them to do it."

These takeaways are propelling them deeper into social issues. A new TB management mobile tool is in the pipeline and was recently awarded funding by the Gates Foundation in their Grand Challenges competition.

Whether or not they receive additional funding from development organizations, the Quraishis utilize the 80% of commercial revenue to finance projects of social impact, a practice commonly referred to as cost-shifting. Yet coincidentally, it's the 12% of charitable work that's garnered them greater attention.

"You learn in the process. It's much more than just about writing a check," Hilmi says.