This is the 11th installment in a continuing series on climate change and the North Carolina coast that is part of the Pulitzer Center’s nationwide Connected Coastlines reporting initiative.

Stormwater that pours onto our roads and drowns our yards has become the most visible and alarming harbinger of what coastal communities are facing with climate change.

As flooding has rapidly worsened in scale and frequency, people are demanding action from their governments. But stormwater management is a costly problem that is not easily solved, even if political will, funding and community sentiment are miraculously aligned.

According to a draft report in March from the Environmental Protection Agency’s Environmental Financial Advisory Board, “Evaluating Stormwater Infrastructure and Financing Task Force,” there is no comprehensive, nationally representative numbers on what is required for stormwater capital and operation and maintenance.

“The needs are great,” the working paper said, “and the funding gap is very wide — estimated to approach $10 billion annually.”

Needs, however, are also urgent.

Of the seven highest rainfall events since 1898 in coastal North Carolina, six have happened within the last 20 years, according to recent research from the University of North Carolina Chapel Hill Institute of Marine Sciences in Morehead City.

The study, published July 2019 in the journal Scientific Reports, pointed to catastrophic rain in hurricanes Floyd in 1999, Matthew in 2016 and Florence in 2018 as a consequence of the warming climate creating more moisture. Florence alone dumped an average of 17.5 inches of rain on 14,000 square-miles of the Carolinas, the report said.

To make matters worse, nontropical storms are also now dumping record amounts of rainfall. Existing drainage has been overwhelmed, exposing the inadequacy of often haphazard and poorly maintained systems. But even some well-designed, modern municipal stormwater systems can no longer keep up.

According to a 2019 study published in Geophysical Research Letters, extreme rainfall events happened 85% more often in the eastern U.S. in 2017 than they did in 1950.

“The take-home message is that infrastructure in most parts of the country is no longer performing at the level that it’s supposed to because of the big changes that we’ve seen in extreme rainfall,” Daniel Wright, the study’s lead author and a hydrologist at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, said in press release.

Depending on whether it’s an urban or rural location, stormwater runoff can be loaded with nonpoint source pollutants such as nitrogen-rich fertilizers, heavy metals, toxic pesticides and fecal bacteria from waterfowl, dogs and septic tanks. It also can be laced with oil, gas and noxious chemicals washed off streets, buildings, lawns and farmland.

In numerous North Carolina coastal communities, including on the Outer Banks, it runs, often unfiltered, directly through outfalls and pipes into the ocean and sounds, or the bays, creeks and rivers that feed into them.

As a result, big storms with lots of runoff overload estuaries and coastal waters with nutrients, sediment and contaminants. Wetlands and recreational waters can be compromised, resulting in fish and shellfish kills, algal blooms and temporarily closed beaches.

The National Pollutant Discharge Elimination System, or NPDES, created by the EPA in 1996 and implemented in parts of North Carolina in 2001, requires larger urban areas to manage stormwater with certain best management practices, or BMPs, to reduce flooding, runoff and pollution impacts on watersheds.

North Carolina’s patchwork stormwater regulations require stricter containment and discharge rules mostly to protect water quality in the 20 coastal counties from stormwater runoff impacts from new development.

But beyond those rules, local governments with smaller populations can decide how to manage its nonpoint source stormwater, that is, discharges that don’t come from a specific source such as a sewer pipe.

The volume of stormwater has become increasingly overwhelming and persistent. In many communities, the largely unseen network of pipes, culverts and ditches that is supposed to take stormwater away from streets and property has been maintained infrequently, if at all. Certainly in North Carolina’s low-lying northeast coast, numerous drainage systems are deteriorating and outmoded. Often, the infrastructure, which could be a century-old ditch attached to half-century-old culvert that’s attached to a series of various sized pipes, crisscrosses and zig-zags over different properties, public and private.

Sometimes, no one knows who is responsible when the system is clogged and numerous properties are flooded. In some areas, drainage is so antiquated, it’s not clear what exists, where it is, what condition it’s in, or who owns it. Regulations to maintain the drainage ditches and structures are spotty or nonexistent.

To complicate matters more, the North Carolina Department of Transportation is responsible for maintenance of all the roadside drainage infrastructure within its right of way. Once water leaves the right of way, however, it becomes the responsibility of the downstream property owner. And severe budget shortfalls have limited the department to mostly piecemeal improvements to its drainage or crisis responses when roads flood.

On the Outer Banks, residents in recent years have been shocked by the amount of water inundating their property even when there is no tropical low. Intense rainstorms have, in a matter of hours, transformed entire neighborhoods into lakes and rushing rivers. Water has flooded buildings that have been dry for decades.

In July 2018, for example, more than 15 inches of rain fell for 10 days straight on Roanoke Island, leaving much of the north end flooded for weeks, even months. An engineer later estimated that 50 million cubic feet of water had fallen.

“The amount of rain we got is crazy,” Brent Johnson, Dare County project manager for grants and waterways, said in a recent interview, referring to the event as a 500-year storm. “We don’t design for that level of water.”

An engineering study of the most affected areas later estimated that drainage improvements would cost about $2.6 million, not including engineering and easement acquisitions.

Dare County has so far dealt with flooding and stormwater on a case-by-case basis. But with more of the unincorporated areas of the county having frequent flooding issues, Johnson said, the county is seeking grant funds to start development of a comprehensive long-term stormwater management plan.

Johnson said that such a plan could manage the watersheds within larger areas to address natural flow and drainage challenges. Realistically, he added, funding for stormwater management would have to be shared between local government, public agencies and private property owners, likely through a combination of bonds, special district taxes and grants.

Roanoke Island illustrates the complexity of draining flooded communities on the coast, where land is flat, water bodies of some form are plentiful and sea level rise is making the water table higher. There is not enough slope or grade in spots, causing water to pool and stagnate. Numerous ditches are routinely clogged with debris, roots and overgrown weeds. Regulations forbid flow to be impeded in ditches, but enforcement is lax. Underground pipes and culverts are often different diameters, broken or improperly connected. What one property owner does or doesn’t do on their land affects whether their neighbor’s property will drain or flood, but even when the issue is addressed in stormwater ordinances, it’s difficult to resolve.

“A lot of the issues we have in our area … you can’t stop the water from coming up from the ocean and the sound,” Johnson said. “That’s what we really have to focus on: How do we get the water back to where it’s supposed to go?”

Each town on the Outer Banks is responsible for its own stormwater management. The town of Nags Head, which is upgrading its stormwater infrastructure in phases, funded through a stormwater fee, got an early start on serious comprehensive improvements.

Farther south, the city of Jacksonville in coastal Onslow County charges a stormwater utility fee, which totals about $5 a month for an average home, to pay for its stormwater management.

Two crews “do nothing but clean drainage,” said Pat Donovan-Brandenburg, the city’s stormwater manager, and other staff are charged with monitoring water quality. Stormwater controls include the slow release of water to prevent flooding and allow it to filter.

Donovan-Brandenburg, who took over the program from the state in 2005, said the city has been steadily making improvements in its infiltration, repairing broken pipes and replacing small pipes with larger ones.

“We’ve been taking care of it little by little,” she said. “No municipality has the money to take care of it all at once.”

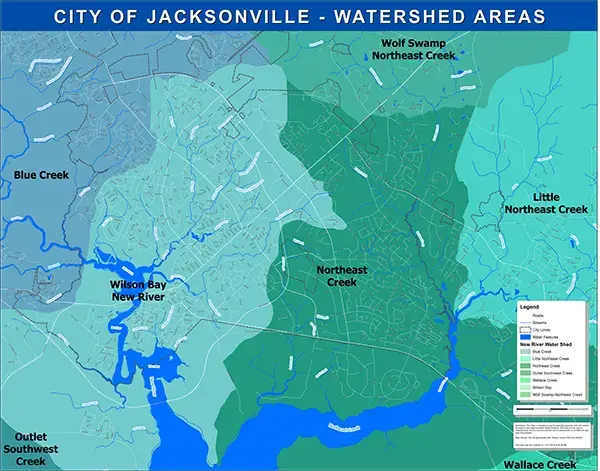

The city is in the middle of the New River watershed and is surrounded by wetlands, which is a lot friendlier to flood control than acres of impermeable asphalt and concrete.

“We have probably a lot of storage area,” Donavan-Brandenburg said. Other advantages are that the area downstream of the city is lightly developed, and the city has no heavy industry.

Jacksonville also requires stormwater permittees to renew every January to make sure that everything is as it should be, whereas the state only requires renewal every 10 years.

“Imagine not cleaning their houses for 10 years,” she said.

Donovan-Brandenburg, who had served for four years as director and is also currently serving as secretary with the Storm Water Association of North Carolina, which supports best practices for stormwater management, said that coastal communities hardest hit by the big storms benefit even more with resiliency measures such as green space that drains and filters stormwater and deep setbacks for waterfront properties. And whether it’s urban or rural, she said, all communities gain by planting and protecting wetlands in the watershed to control stormwater while promoting cleaner water and healthier fisheries.

“Wetlands do much better with flooding and wave energy than a man-made seawall,” Donovan-Brandenburg said.

Also, simple measures as grass alongside roads — such as grassy swales and grass ditches — slows down water to “a nonerosive rate,” she said, adding: “Curb and gutter allows water to pick up speed and velocity.”

The stormwater panel has been urging NCDOT to use some of those kinds of BMPs on Interstate 95 and I-40.

Clearly, the best answer for stormwater management, she said, “even in the mountains, is not taking away the floodplain. One thing that everybody can do is start planting more trees.”

The North Carolina Coastal Federation and The Pew Charitable Trusts in March launched a yearlong initiative, “Advancing Nature-based Stormwater Strategies in North Carolina,” to encourage natural solutions to flood risk.

By merging the expertise of academics, developers, investors, landscape architects, conservationists and others, the effort is working to promote cooperative strategies that allow stormwater to filter into the ground, rather than runoff into the waterways. Permeable pavement, rain gardens, cisterns, living shorelines and preserved green spaces are some ways to engineer roads and landscapes that help reduce runoff and erosion.

The working group is expected to issue recommendations this winter, according to Pew.

Some environmentally sensible stormwater control tactics studied by academic partners include bioretention devices, wet ponds, green roofs, stormwater wetlands, grass swales, sand filters and dry ponds. UNC campuses and North Carolina State University have programs that study stormwater issues.

In 2019, UNC-Chapel Hill’s Environmental Finance Center released a report on stormwater funding. Compared with water and wastewater infrastructure needs, the report said, it has been difficult to quantify costs of stormwater infrastructure needs.

“Recently, however, there has been a change in this trend, and more state and federal entities are starting to focus on identifying stormwater needs,” according to the report. “Communities are going to have to identify dedicated sources of revenue for stormwater and to be more intentional about matching revenue generation with capital needs as the future of the North Carolina stormwater landscape develops.”

Even in extraordinary times of overlapping public emergencies, flooding will continue. Without adequate stormwater infrastructure, communities will be condemned to a future of polluted water and flooded neighborhoods and downtowns.

“Stormwater infrastructure requires funding and it has been neglected, or inadequately funded, for far too long,” the EPA said in the draft stormwater working paper, comparing the investment to the federal highway system.

“Municipalities and local utilities need federal and state help in defining long-term reliable funding sources,” the draft report said. “Funding must be available in all states and be sufficient to support both capital expenditures and long-term operation and maintenance costs.”