Editors Note: For the full-multimedia presentation, please click here.

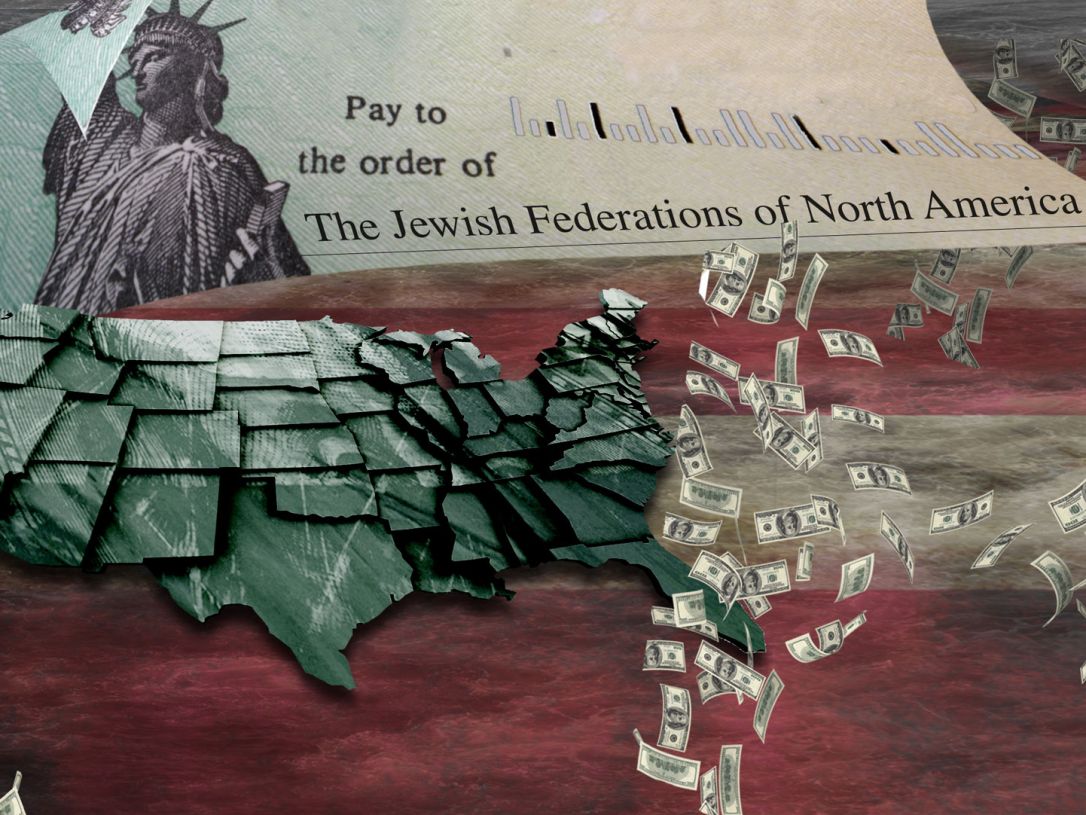

Supported generously by American and Canadian Jews, the Jewish Federations of North America network has a turnover of billions of dollars a year. Collectively the network of local federations and foundations is one of the biggest charity systems in America. These organizations collect donations, distribute the money, and support their own mechanisms. How much do the federations spend on the greater good of Judaism and Israel, and how much on themselves and their own staff?

The raw data is available through their tax records, which are in the public domain. Less obvious is how their affairs are governed.

Now for the first time the federations' finances and practices have been mapped by Haaretz, in collaboration with the Pulitzer Center on Crisis Reporting. Figures from four years of tax reports by every Jewish Federation in the United States, and dozens of community foundations, have been concentrated into interactive maps. [To view maps

please visit the Federation Files on Haaretz.] What they show may not always be what you expect, including some salaries that seem to be beyond the norm among American nonprofits, duplication in efforts that might seem to achieve little beyond the employment of friends and family, and other potentially problematic practices.

Haaretz also examined the finances of the Jewish Federations of North America, a nonprofit organization by its own right. Serving as the federations and communities umbrella organization, the JFNA provides federations with support and guidance. It also serves as a pipeline for the majority of the federations' support in countries outside the U.S., chiefly Israel.

Click here to access all the Federations' 990 tax forms (Return of Organization Exempt From Income Tax), broken down by state and city.

Big business

The Jewish Federations is a central institution to American Jewry. Some worry about the Jewish population of America shrinking, but the line snaking past security to get into the JFNA General Assembly at the Hilton Hotel in Washington, D.C. in November 2016 seemed endless.

Existing twice as long as the State of Israel itself, the federations' overarching purpose is to promote Jewish life and values. Over generations, a sprawling system of 148 Jewish federations, ten in Canada and 138 in the U.S. was created, plus about 300

network communities. These foundations in turn support thousands of institutions and nonprofit organizations in America, from schools and libraries to welfare and culture centers to synagogues.

The federations finance help for homebound seniors and the disabled, and help Holocaust survivors with housing, health care, nutrition needs and more. They helped bring the Ethiopian Jews to Israel and they support Birthright trips to Israel. They also support programs and projects around the world, providing food and drugs during disasters, such as the 2015 earthquake in Nepal. During the Gaza campaign in 2014, they raised $55 million to send to Israel. During the Russian military intervention in 2014, they sent food and medicine to more than 30,000 elderly Jews and 4,600 children in Ukraine. Most recently,

JFNA launched a campaign to help victims of Hurricane Harvey.

The list goes on, and it’s impressive. Yet the research into their public records and conversations with former and existing employees about the financing and governance of the Jewish Federations has discovered at least some run less like volunteer organizations and more like family firms.

Nor is there overarching oversight of their governance, beyond the regular regulation of charities under law.

However much they benefit the local community, and Israel, at least some take enviable care of their own, including through salaries several times higher than the norm at nonprofit organizations, and through loans under terms they refuse to disclose.

Many of the federations also quietly support the settlement movement in Israel, saying when pressed that they exist to help Jews wherever they may live.

A mammoth industry

Let's start with the financing of JFNA itself. The JFNA mission statement states that collectively the federations are “among the top 10 charities" in the continent in “caregiving, aging, philanthropy, disability, foreign policy, homeland security and health care.” Headquartered in Manhattan, across the street from Wall Street’s iconic Charging Bull statue, JFNA reported having $400 million in assets in 2015. According to the JFNA's own website, the combined federations and communities’ assets reach $16 billion, and it raises approximately $900 million a year.

This is a big portion of total Jewish philanthropic activity in the United States, which The Forward estimated at $26 billion in 2014.

Most of the federations' support goes to local Jewish causes, but each also donates to Israel, via the JFNA or directly. The percentage of the money they raise that they donate to Israel varies, but typically amounts to at least 10 percent of the donations collected in a given year.

About 75 percent of the JFNA funds sent to Israel arrive there via a different entity, called the United Israel Appeal.

The Jewish Agency is the operating agent of the UIA on the ground in Israel. According to the latest records available, in 2014 UIA sent $213 million to Israel, down from $231 million the year before. The rest of the JFNA money that ends up in Israel arrives mainly via the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee.

The main findings

Tax records show that in the four years 2012 to 2015, donations, expenditure and total assets of all the federations combined all increased year by year. Spending on salaries increased in nominal terms but remained quite steady in terms of percent of revenues: about a fifth of total donations.

While support for Israel is clear and loudly proclaimed, support for the settlers and for organizations operating beyond the Green Line is a sensitive issue for the Federations, on which they prefer to remain silent. JFNA guidelines are vague and hard information about the extent of support is meager. Nonetheless, Haaretz has learned that Federation funds have been supporting some of the most hard-line settlers, for example in Hebron and Silwan, East Jerusalem, and organizations aspiring to change the status quo on the Temple Mount. Over the four years from 2012 to 2015, individual federations directly donated about $6 million beyond the Green Line. Although figures for 2015 are partial, it seems to have been a banner year for settlers in the West Bank, who got more than $1.6 million.

For comparison, the federations spent about the same amount, specifically $6.6 million from 2012 to 2015, lobbying to promote Jewish goals.

The value of a job

At some federations, officials serve on a volunteer basis. At others, they are paid munificently.

For example, Jay Sanderson, president and CEO of the Los Angeles Federation, made about $550,000 in 2015, over $200,000 more than an average peer nonprofit organizations pay their talent. That year the L.A. Federation donated $26 million.

In other words, the federation president’s pay was equivalent to 2 percent of the federation's donations. That year, incidentally, the federation’s assets dwindled by about $3 million, from about $153 million to about $150 million.

"I continue to be concerned that you are taking a seemingly one dimensional approach to this piece and to the immeasurable impact of the Federation movement," Sanderson replied to Haaretz. "How do Federation Executive positions compare to these other non-profits? How do you value each position and job performance? I am deeply proud of my work and my 24-7 commitment to my community and to the Jewish community. Federations are essential to the past, present and future of the Jewish people."

The JFNA itself commented that the search for a Federation CEO "often involves a team of professional and lay people and can take months. Candidates must demonstrate a range of skills; including fundraising, community planning, agency relations, volunteer engagement, leadership development, knowledge of Israel and overseas philanthropy, advocacy and more. Communities want to attract and retain the best talent and, like all organizations, utilize all of the tools at their disposal."

Some of the federations also lend money to their people. For example, Seattle Federation President Keith Dvorchik, who was paid about a quarter of a million dollars in 2015, also borrowed $100,000 to cover moving costs. Stacye Zeisler, the federation’s chief marketing officer, said the loan was approved by the federation executive committee and is being returned with interest.

Our research also found extraordinary benefits: to give just one example, the Chicago Federation granted its president, Steven Nasatir, $50,000 annually from age 64 until the day of his death. These financial arrangements “were determined by the federation’s Compensation Committee based on a variety of criteria, including job performance, length of service, and national compensation surveys,” says Aaron Cohen, the Chicago federation’s VP Communications.

The Haaretz mapping project prompted the JFNA to issue an internal memo, classified as secret, to the managements of the various Federations at the end of January, warning of requests from Haaretz for information. “We are working with the JFNA and outside consultants on responses to help set the record straight and mitigate any potential negative impacts the story might have,” the document stated and also said, “Because of the sensitive nature of this story we respectfully request that if you are contacted directly (by the reporters) you politely tell them that you ‘will get back to them at a more convenient time’ and notify the Executive Director to discuss potential responses.”

At the JFNA General Assembly in November 2016, when Haaretz privately asked various Federation members questions about issues such as salaries, possible nepotism or support for projects beyond the Green Line, the evasions were less subtle. “I’m really in a hurry,” one of the heads of the Boston Federation said after he had already agreed to respond to questions. When Haaretz asked to talk with him at a later time, he said, “No, I don’t have a business card on me."