Eskom announced earlier this year that it would begin phasing out five coal-fired power stations, framing the decision to close the ageing plants as the fault of renewable energy.

While many people argued this interpretation was wrong because new coal is no longer competitive with other forms of electricity generation, the decision indicates coal’s faltering dominance over the energy industry.

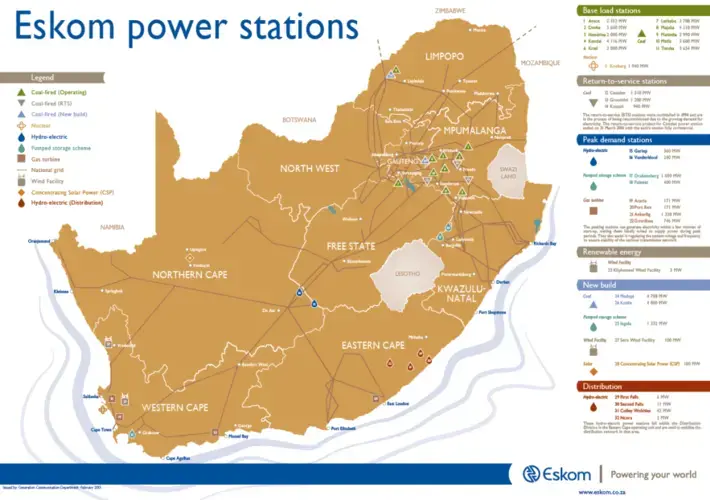

Coal accounts for about 83% of Eskom’s electricity generation, and the battle has now begun to determine which forms of power generation will be tapped to keep the lights on in the future.

Why coal is not the future

The decline of coal power is signalled by the industry’s inability to keep costs low, to meet environmental regulations and to keep pace with technological advances in other forms of generation.

In February 2014, Eskom applied to postpone deadlines for complying with minimum emissions standards at 14 of its coal-fired and two of its gas-fired power stations. The Department of Environmental Affairs granted all 16 requests a year later, and Eskom is already preparing to reapply at two plants.

In a statement, Eskom’s media department told Oxpeckers it relies on a “phased” emissions reduction plan due to the high cost of retrofitting old plants. The statement said Eskom had committed R107-billion to reducing emissions.

Coal took a further hit in March this year, as the High Court in Pretoria ruled the Department of Environmental Affairs must consider a climate change impact assessment report when granting licences to the Thabametsi Power Project, a new coal-fired power station proposed in Limpopo.

Nuclear deal

Richard Worthington, who researches energy policy for Earthlife Africa Johannesburg, says Eskom is trying to spin the story of coal’s demise and renewables’ costs.

“The narrative that Eskom is presenting is a self-serving narrative to bolster their prospects of a big nuclear deal, which will see them rolling in money for a long time, especially the upper management, if they don’t go totally bankrupt,” he said.

For the country to meet its intended contribution to the Paris Agreement, the international climate change deal to limit global temperature rise to 1.5 degrees Celsius, the country will need to move away from coal, Worthington and many others argue.

“South Africa’s mitigation component of its nationally determined contribution takes the form of a peak, plateau and decline [greenhouse gas] emissions trajectory range. Its emissions by 2025 and 2030 will be in a range between 398Mt and 614Mt [of carbon dioxide equivalent],” Department of Environmental Affairs spokesperson Albi Modise said.

The country’s plan to meet these goals comes from the Department of Energy, which in November 2016 published models for the country’s future energy portfolio in the form of the Integrated Resource Plan, or IRP (more information here).

The IRP came with significant controversy, as its model called for high levels of nuclear generation, capped the amount of electricity generation that could be derived from renewables and, in some instances, relied on outdated data.

The Council for Scientific and Industrial Research (CSIR) responded with its own least-cost projections in January and found that a future heavy with renewable energy is the cheapest option, calling the IRP’s cap on renewables “not technically/economically justified”.

Models in the IRP call for only between 23% and 29% of the country’s electricity to come from wind and solar photovoltaic – solar panels that convert sunlight directly into electricity – by 2050. CSIR’s low-cost model asks for 79% to come from those two sources and for coal to disappear.

The entire coal-to-electricity industry is experiencing a shakeup, as Eskom moves away from its traditional contracts for purchasing coal and pushes its suppliers to maintain a majority black ownership. These moves have proven unattractive for large companies, and coal major Anglo American is selling its mines supplying Eskom.

Jesse Burton, who researches energy policy at the University of Cape Town’s Energy Research Centre, said a transition away from coal dependence does not have to be an economic burden.

“If you didn’t have to buy electricity from Eskom, you could actually get it cheaper from independent power producers,” Burton said, calling the evolving power generation industry a “breakdown” of a “monopoly structure”.

Additionally, Eskom has massive and growing funds tied up in building the Medupi and Kusile coal-fired power stations, projects that Eskom now expects to be completed by 2022.

“Where you might get stranded assets is, of course, if you build very large new mines like you need for Kusile, and Kusile is so inefficiently built that it can never compete in the electricity market,” Burton said.

The Department of Energy did not respond to repeated requests for comment on the IRP and future plans for electricity generation.

The energy department’s alternative

As indicated by the IRP, the Department of Energy is aiming for nuclear to take the place of coal as a low-emissions alternative.

However, the Western Cape High Court recently set aside proposed nuclear procurement agreements with Russia, South Korea and the United States, calling the deals “unlawful and unconstitutional”. Energy Minister Mmamoloko Kubayi announced on May 13 she would not appeal the decision, but would continue to pursue nuclear as an integral part of the future energy mix.

Questions abound about the potential for corruption if new nuclear – and its expected price tag near R1-trillion – is approved.

According to an analysis of Oxpeckers’ #MineAlert platform, there are about 130 mines around the country involved in uranium extraction, a resource necessary for nuclear plants.

The Gupta family’s Oakbay Resources and Energy Limited owns a dedicated uranium mine called Shiva Uranium, leading to speculation that this might be influencing the government’s push for nuclear power.

In a November 2014 press release announcing the company’s listing on the Johannesburg Stock Exchange, Oakbay said Shiva Uranium would tap into one of the five largest uranium ore bodies in the world.

However, raw uranium ore needs to be sent abroad – to countries such as the US or France – for refining before the resource ever enters a power station. Because of this and because new nuclear capacity is still years away, experts caution against drawing links between the Gupta family and the government’s push for nuclear.

“It’s a little bit more complicated than that,” Burton said. “I mean, there’s a big difference between the Guptas owning what seems to be a very uncompetitive uranium mine and actually having that uranium going into a power plant.”

Instead, experts argue the contracts associated with the potential nuclear build would be easy targets for corruption.

“The base case scenario [in the IRP] is an attempt to justify a commitment to a nuclear procurement programme, which is not related to our electricity supply system needs but related to the deal-making people want to do,” Worthington said. “In no way is the nuclear procurement driven by energy planning. It never has been.”

Already in September last year, reports surfaced that the son of one of the president’s close friends received contracts from the nuclear build programme.

“What we have seen, though, is politically connected individuals getting deals already related to the nuclear programme,” Burton said.

This debate includes Eskom, where chief executive Brian Molefe resigned – or asked for early retirement – after being implicated in the State of Capture report and was then reappointed last week, and where former acting chief executive Matshela Koko is fighting allegations of contracts improperly granted to a company where his stepdaughter served as a director.

Eskom’s media department said, “New potential nuclear capacity will be procured through fair, equitable, transparent, competitive and cost-effective tendering procedures.”

The power utility also faces fallout from the so-called “Dentons Report”, a report commissioned by the board to determine the challenges Eskom is facing. The Dentons Report had numerous findings ranging from increasing coal costs to a tendency to use “non-competitive procurement”.

“After reviewing the report, the board found there were no new issues that were revealed by the inquiry. This confirmed the board’s assessment of the areas of improvement that was required to turn the business around,” Eskom’s statement said.

The statement also said the “majority of the recommendations” had been implemented by November 2016.

The minerals department’s alternative

Despite an organised opposition led by community groups in the Karoo, the Department of Mineral Resources recently reinitiated its push for hydraulic fracturing, or fracking.

Minister Mosebenzi Zwane gave a speech in March in which he said South Africa was moving forward with fracking, in part, to get away from a near-total reliance on coal for electricity generation, according to his pre-written remarks.

“It is for this reason that government has taken a decision to diversify the country’s energy basket with the aim of providing a cost-competitive energy security and to significantly reduce the carbon footprint,” he said, alluding to the disputed hypothesis that methane emissions from fracking and burning natural gas are a long-term, low-impact alternative to coal.

In mid-May, acting chief executive of Petroleum Agency SA, Lindiwe Mekwe, told Reuters that five applications for exploration licences are under review, including applications submitted by Royal Dutch Shell, Falcon Oil and Gas, and Bundu Gas & Oil. Although objections on environmental grounds delayed the process in the semi-arid Karoo basin, Mekwe said licences could be granted as early as September.

While many experts, including Worthington, say gas could bridge the energy transition away from coal and toward renewables, uncertainty remains about whether fracking would actually produce that gas. Burton points out that companies would not be under an obligation to sell gas under market value, indicating imported gas might be an alternative.

Zwane said the government’s decision was “based on the balance of available scientific evidence”.

A 1,400-page version of the much-anticipated strategic assessment of proposed shale gas development (full report here) was published in November after more than 20 months of study, and the report was not in step with Zwane’s comments.

Zwane claimed there were up to 50-trillion cubic feet (tcf) of recoverable shale gas, significantly less than the 485tcf the US Energy Information Administration originally estimated. However, the scientific assessment found the economically recoverable volume was actually between only 5tcf and 20tcf.

As projections shrink, companies investing in fracking have pulled out of the country over the past several years.

If 20tcf were found, the study said, the industry would consume up to 65.5-million cubic metres of water, would require two million truck visits to the environmentally sensitive Karoo and would build 4,100 production wells.

“[Shale gas development] could deliver highly significant economic opportunities, but its extractive nature could also bring economic risks. In both respects [shale gas development] is little different to other types of mining,” the study found.

The study went on to predict that renewable energy would become the region’s biggest economic driver if fracking did not happen. Even if exploration licences were given, the study found the industry would still be up to 11 years away from production.

“We’re many years from fracking,” Burton said. “I don’t see it being successful because the politics of South Africa are such that people don’t want to invest. It’s not viewed as a safe investment space.”

The Department of Mineral Resources did not respond to repeated requests for comment on its activities promoting fracking.

Civil society’s alternative

Experts argue that in order to meet any climate change-related goals, renewable electricity generation is the answer.

“There’s no justification on long-term constraints of renewable input into the system,” Worthington said of the IRP’s artificial cap on renewables. He helped compile a report called Plan A, which argues wind and sunlight are extremely plentiful in South Africa and could support the country’s electricity consumption.

The CSIR’s response to the IRP echoes some of this view and claims its own report’s high-renewables mix would produce electricity at R90-billion cheaper per year than the 2016 IRP would by 2050.

Arguments against renewables exist, including intermittency – the lack of electricity generation when the wind does not blow, or the sun does not shine – and the need for expensive grid expansion.

“Technical problems related to intermittency in renewables and those sorts of things can actually be dealt with quite easily. They’re not the big bad wolf that usually the coal and nuclear lobby pretend that they are,” Burton said.

Bids for independent power producers’ renewable projects have been about 40% cheaper than those for coal.

“Eskom supports the introduction of the renewable energy independent power producers as envisaged in government’s Renewable Energy Independent Power Producers Programme,” Eskom said in its statement. The utility has signed 64 power purchase agreements, totalling 4,000MW, under this programme and plans to sign agreements worth another 2,383MW of generation from renewables soon.

Instability in coal has also produced panic in organised labour. Worried about their jobs, coal truckers protested the announcement that the five coal-fired plants would be closed.

But renewable energy advocates say the transition to renewables would create jobs as well. In the US, for example, a report by the Environmental Defense Fund and Meister Consultants Group found that solar and wind projects are creating jobs at a rate 12 times that of the rest of the economy.

“What our plan for electricity supply should be is that we don’t build any new coal or any new nuclear, for starters,” Worthington said. “Renewables make a better value proposition.”