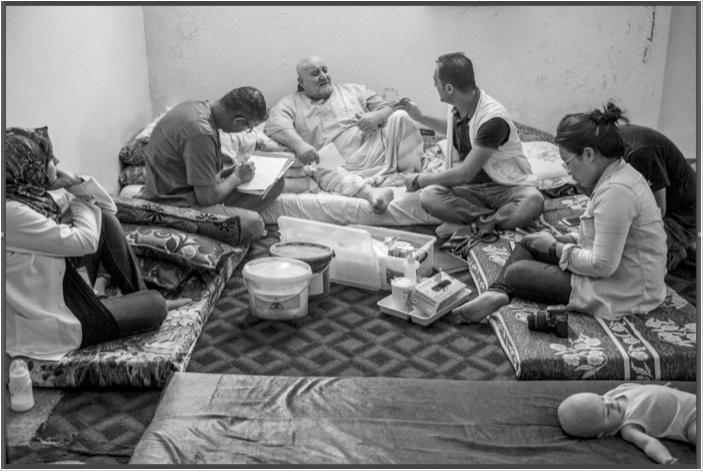

Many Syrian refugees, like the man in the center of the photo above, continue to deteriorate from chronic diseases, despite having moved beyond acute crisis. To figure out how to improve their situations, doctors are collecting data with a new technology, called the Dharma Platform, that they hope helps them figure out which interventions work best. Dharma was created by a fed-up first-responder who wanted anyone to be able to build the digital tool he or she needed to collect and share data, and to visualize the results off-line and in real time. Now Dharma is being piloted by doctors operating clandestinely in Syria, and by those serving refugees in Iraq, Turkey, Lebanon, and Jordan (pictured above).

Photo by @neilbrandvold, with words by @amaxmen. Read the full story published by Nature.

Jordanian Princess Sumaya bint El Hassan sees science as a means to transcend volatile politics in the Middle East. “All of us in this region face issues with energy and water, so we must speak the same language,” she says. “A bird with Avian Flu does not know whether there is a peace accord between Israel and Jordan, it will still fly across.” This November, Princess Sumaya will chair the World Science Forum in Jordan. It will be the first time the conference is held in the Middle East.

Photo by @neilbrandvold, with words by @amaxmen. Read the full story published by Nature.

We shared tea with the mayor of Umm el Jimal in northern Jordan one sweltering afternoon. He told us about the town’s 2,000-year-old water system, currently being restored. The system consists of a series of channels filled by runoff from mountains across the border in Syria that drain into ancient reservoirs. This source has become important again as wells run dry and salty. The project is an outlier among dozens of high-tech innovations being tested in Jordan to stave off water scarcity. Their findings may prove useful around the world. A recent report from U.S. intelligence warns that water scarcity, when combined with poverty, social tensions, ineffectual leadership, and weak political institutions, will result in conflict in the near future.

Photo by @neilbrandvold, with words by @amaxmen. Read the story at Nature News.

From Ar Ramtha, in northern Jordan, you can see smoke across the border in Syria. People from Ar Ramtha recall fondly their visits to Daraa, in southern Syria, before the first uprisings against the regime began there in 2011. When that happened, Ar Ramtha resident Mohammed Shouboul told me, “Every Jordanian here was eager to host Syrians fleeing from the conflict. They were our partners. They used to send us tomatoes and we would send them cucumbers.”

Jordan has taken in 660,000 Syrian refugees since 2011. That’s 10% the country’s 2011 population size. Turkey and Lebanon have taken in 4.1 million. The United States has resettled 18,000. That’s .005% of the population size of the richest country in the world. As opposed to migrants who often move to improve their future prospects, refugees move to save their lives. The United Nations writes: “If other countries do not let [refugees] in, and do not help them once they are in, they may be condemning them to death.”

Photo by @neilbrandvold, with words by @amaxmen. Translation by @ibraheemshaheen. Related story at Nature.

Taleb and Sahra* fled to Jordan after the Syrian government cracked down on southern Syria. The conflict began there in 2011 when students spray-painted anti-regime slogans on walls. The students were arrested and their fingernails ripped out. Taleb and Sahra told us how in the months that followed, soldiers burned one of their sons to death. Another was released from jail with scars from torture. Taleb can no longer walk due to multiple strokes. Sahra has a bad back. “After they killed my son and took my child, I used to walk down the streets and say, I don’t care anymore,” Sahra says. “I’m really sick now. My body is sick.” Sahra cleans and cares for Taleb: “I don’t leave since my heart beats for him.” But the couple smiles when they look at one another. They recall how they met 40 years ago, and the farm where Sahra made cheese, pastries, and bread. “The conflict makes us forget nice days,” she tells us, “but I can recall the love.”

An August 3 report shows that violent deaths in the Middle East increased by 850% between 1990 and 2015. Deaths from chronic disease have risen as well, likely from stress and the deterioration of health systems.

Photo by @neilbrandvold, with words by @amaxmen. Translation by @ibraheemshaheen. Read the full story published by Nature.

*Names have been changed to protect identities

When the Syrian conflict escalated in 2011, diabetes became a very deadly condition. Khaled* recalls how hospitals became places of warfare, and doctors became targets. Syrian President Bashar al-Assad effectively made it a crime to treat people in opposition-held regions of the country, and 826 healthcare workers have been killed by execution, bombs, or tortured to death in the past six years. As Syria’s health systems deteriorate, civilians like Khaled have suffered and died from everyday complications that could normally be controlled. According to August reports in the International Journal of Public Health, death from war, terrorism, and state-sanctioned executions increased by 1027% between 1990 and 2015 in the Middle East. During the same period, the death rate from diabetes grew by 216%.

Photo by @neilbrandvold, with words by @amaxmen. Read our related story at Nature.

*Name has been changed to protect his identity

I talk with Mahmoud Subeihat at a clinic in Ar Ramtha, a town in northern Jordan. He said his house shakes from bombs falling on his neighbors just across the border in Syria. “They are living in a very bad situation,” he says. “This is not usual. God be with them. God give them patience. Jordan welcomes them. I’m telling you this as an act, not words. We are all one. Labor problems or not, we are all one.”

Photo by @neilbrandvold, with words by @amaxmen.