Mabinty seemed worried as she sat outside on a bench in the sun. It was hot, and she could have moved to a nearby bench in the shade of a tree. But Mabinty, heavily pregnant, avoided the shady bench: It was occupied by a family with obvious symptoms of Ebola. One man reeled with feverish delirium, speaking but making little sense.

I met Mabinty in December at a holding center—a sort of halfway house where patients with suspected Ebola cases wait for beds in treatment centers—in Makeni, a city in central Sierra Leone. Apart from Mabinty's understandable fear, she seemed perfectly healthy. She had ended up in the holding center because, after feeling some abdominal pain, she had reported to a local hospital to make sure there was nothing wrong with her baby. Fearing that Mabinty might have Ebola, the hospital staff had directed her to go get an Ebola test before they would treat her.

When I met Mabinty, she was stuck in the holding center awaiting her test results, separated from her family and living in close quarters with sick Ebola patients. Every day Mabinty spent there put her at risk of becoming infected herself—if she was not already.

Mabinty's story speaks to one of the knock-on tragedies of the Ebola epidemic. Apart from killing infected people—10,000 so far—the epidemic has disrupted existing health care programs and created new health problems in its wake.

Because many health care workers treating pregnant patients with Ebola contracted the disease, pregnant women are finding it difficult to get even routine care. Researchers estimate that this will as much as double the maternal mortality rate—the percentage of women who die in childbirth—in the Ebola-affected countries of Sierra Leone, Guinea and Liberia. The epidemic has also disrupted malaria prevention programs and care for patients with HIV and has inflicted mental trauma that may last for years to come.

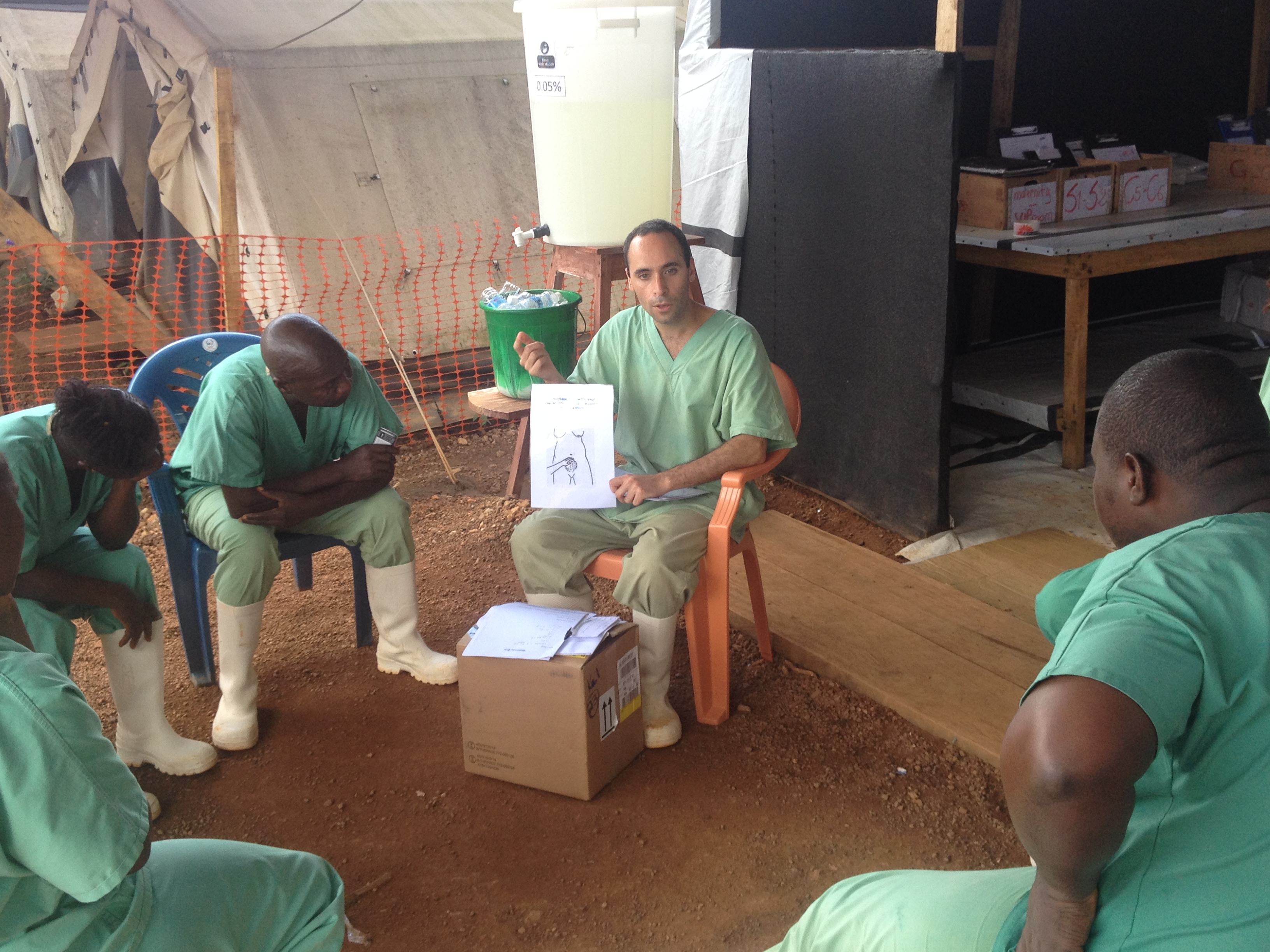

For health workers, the decision to stop providing care has been tremendously difficult. I met Benjamin Black, an obstetrician with the aid group Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF/Doctors without Borders), in December 2014 in Bo, Sierra Leone. He told me of the events that led the group to make the heart-wrenching decision to stop treating pregnant women at an MSF clinic there last August.

The clinic had specialized in treating women with life-threatening emergency obstetric complications. But the symptoms of Ebola mimic the symptoms of many of these complications. Doctors had little time to decide whether or not a woman arriving at the clinic might actually have Ebola. Test results took as long as 24 hours to arrive.

At three o' clock in the morning one night last July, a woman in her last weeks of pregnancy arrived at the clinic. She was having seizures and bleeding from the mouth. Both of these are symptoms of Ebola, but there were other possible explanations: The patient might be bleeding because she had been seizing for 24 hours and could have bitten her tongue; she had also fallen and wounded her face the day before. Or she might be bleeding due to a potentially fatal pregnancy complication called HELLP syndrome that is similar to pre-eclampsia, and is best treated by speedily delivering a baby.

The doctors debated what to do.

"We know that we can deliver this baby and probably we're going to save her life," some said.

Others were troubled because the woman had come from so far away, from an area known to harbor Ebola at the time. "We just can't take the chance," they said.

In the end, the doctors decided to isolate the patient and treat her as a suspected case of Ebola. They agreed that they would treat her eclampsia, but would not deliver her baby, because they could not risk exposing clinic staff to her potentially infectious blood. They sent for an Ebola test. Hours later, while they were awaiting the results, the woman died.

Black worried. "What have we done?" he asked himself. "Have we just put this woman in isolation and let her die?"

Finally, the test result came back: it was positive. But the experience had shaken everyone. In the weeks that followed, the clinic staff felt they were always one wrong call away from catastrophe as they tried to sort out Ebola patients from the rest.

"If we ended up infecting all of our midwives, all of our birthing attendants, our expatriate staff as well as our national staff, the impact on maternal healthcare in this country would have been huge," Black says. That was what finally led the clinic to stop accepting pregnant patients in August.

The clinic's obstetric health services remain closed today. Though the epidemic had been waning for most of this year, the past few weeks have brought bad news: The number of new cases per week has stayed in the double digits in Guinea and Sierra Leone all year. And Liberia saw its first new case in three weeks on March 20.

"Things are not at all looking good here," Séverine Caluwaerts, MSF's gynecologist technical referrent on the ground in Conakry told me via email on 24 March. She estimates that MSF will not be able to start regular obstetric services until at least mid-April, or possibly May.

As for Mabinty, she was lucky. After weeks in the holding center, she finally learned that she was Ebola-free and returned home to her family on December 14. In February, Mabinty delivered a healthy baby girl; as of March 27, they are both well. Though they never became infected, they are Ebola survivors nonetheless.