At night, most light comes from the passing semi-trucks speeding past the highway connecting Monterrey and Nuevo Laredo, a road often dubbed the highway of death. "Oscar" (name altered due to safety concerns) is a Nicaraguan who is escaping domestic violence and has made most of the journey from his home country to northern Mexico on foot. When he looks up, he sees one pair of headlights gets brighter before the truck slows to a stop beside him. The window rolls down and the driver questions Oscar on where he’s trying to go. Oscar tells him the border and asks for a ride, but the driver responds that while all the trucks here are indeed going to the border, they’re headed toward the city of Nuevo Laredo.

As a nonprofit journalism organization, we depend on your support to fund more than 170 reporting projects every year on critical global and local issues. Donate any amount today to become a Pulitzer Center Champion and receive exclusive benefits!

Oscar insists, then the driver replies, “Do you want to die? There are other ways to die.”

Although Oscar arrived at Casa del Migrante Nazareth shelter in Nuevo Laredo safely, he says this part of the trip is agonizing. Friends in the United States who originally said they’d help changed their mind out of fear of deportation, and Oscar has little idea of how the asylum process works. For three months, he’s remained stuck in the shelter, in one of the most dangerous cities to be a migrant in Mexico.

Violence Everywhere on the Mexican Side of the Border

Nuevo Laredo sits in the territory of the Noreste cartel, an offshoot of Los Zetas, a militant criminal organization that orchestrated mass terror in the city during the 2010s. Close to 75 percent of migrants in Nuevo Laredo report being victim to kidnappings, often with the intention of extorting their family for money, or for recruitment. In 2019, Aaron Mendez, the director of another shelter in the city, was reportedly kidnapped for refusing to hand over Cuban migrants to organized crime and has remained disappeared to this day.

One migrant from southern Mexico, Melisa (who asked that her last name be withheld), recalls the fear she felt when tattooed men approached her and her husband by the bridge into the U.S. They demanded to know her reasons for traveling to the area and threatened bad things would happen to her if she didn’t take the “job” they were offering, without explaining what the job was.

From the same shelter, Salvadorean "Carlos" (name altered for safety) recounts the extreme stress his family has experienced after waiting more than six months to enter the U.S. In his country, he’d been kidnapped and tortured for three days, and though he’s thankful for his own health, he says his two children are getting too thin and that they need medical help due to the emotional trauma they’ve endured. His daughter grew so physically ill from what Carlos believes was stress that she had to stay at a local hospital for days.

But for many migrants in Laredo, Texas, violence doesn’t end with the first step on American soil.

Violence Spills Onto American Side

Matthew Hudak, chief patrol agent of the Laredo Sector of the U.S. Border Patrol, says: “We see a combination here of migrants being held against their will in stash house locations by the smugglers and held there often with gangs and weapons.”

While the immediate, tactical reason might be so that undocumented people don’t wander and alert law enforcement, the same means of force is used to extort migrants and their families for thousands of dollars. According to Hudak, there have been over 4,700 arrests of migrants this year at stash house locations, a 775 percent increase from the same time last year.

For Hudak, a part of attacking stash houses is protecting migrants from being stacked into the back of semi-trucks in 100-degree heat and doused with dangerous chemicals to hide their scent from canines on their way to other locations. However, the relationship between migrants, law enforcement, and criminal groups is not a simple one.

In 2018, a Guatemalan woman was killed during a confrontation between migrants and Border Patrol. Laredo Border Patrol agents have been charged with colluding with smugglers before, and one study found that as many as 40 percent of veteran officers are involved with human smuggling.

In La Frontera Shelter, a facility for migrants in Laredo, a Honduran woman, "Sandra" (name altered for safety), cried in her seat from terror after remembering encounters with Border Patrol. Although she and her baby had been allowed into Texas, her 20-year-old daughter had been denied entry and was sent to Reynosa, Mexico, a city that suffered a massacre of at least 15 innocent people on June 20.

According to Chief Hudak, Title 42 greatly expedited the process of deportation: “We can quickly expel them within a matter of minutes or hours versus detaining them for several days.” Over 750,000 people have been expelled due to Title 42 as of June 2021, with 77,245 coming out of the Laredo region. But Title 42 has created a major, unique problem for those being deported to Nuevo Laredo. A local Nuevo Laredo journalist found that the government was ignoring Title 42 deportees, because their lack of deportation documentation meant they had no legal obligation to care for them.

Shelters as Havens

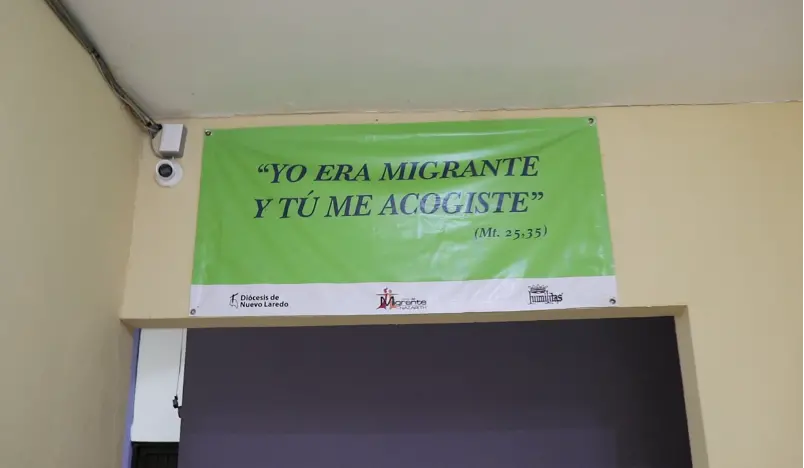

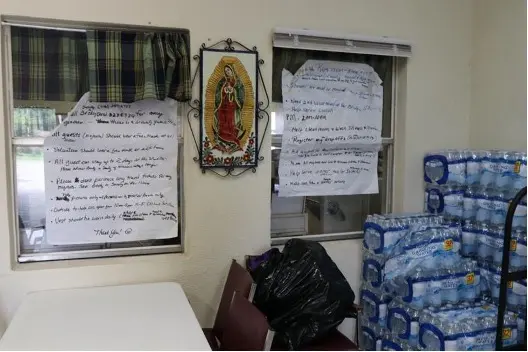

In between the violence on each side, shelters have been a source of relief for many migrants who find the border dangerous. The Casa del Migrante Nazareth has police officers stationed by the door, an iron locked gate, and other measures for heavy security. A 15-year-old migrant from the southern Mexican state of Guerrero told of the violent threats her mother and sisters received and how arriving at the shelter, she felt safe and blessed they always had enough food.

"Jose" (name altered for safety) said he was horrifically traumatized after being hunted by a gang in Honduras and watching his home burned to the ground. Though he emphasized, “I’m scared, I’m scared in Mexico,” he said his experience in the shelter had been one of finding some calm from all the terror.

Of the 22 people at the shelter asked for comment, all claimed that they had been treated incredibly well and felt consistently supported. Oscar, the Nicaraguan who had been warned of coming to Nuevo Laredo by truckers, responded by saying his experience had been very beautiful because it showed him we can all “really live as brothers without caring for race and color.”

In Laredo, the 15 migrants interviewed in La Frontera Shelter similarly claim to feel safe and thankful, despite a recent protest against one shelter location, and some shortages of food and clothes.

Two Honduran women, who stood in line for food and returned empty-handed to their 1- and 3-year-old, lamented that while “one can always skip a meal, what about the children?”

According to Rebecca Solloa, director of Catholic Charities of Laredo, La Frontera was primarily supported by federal funding, but donations and volunteer support have slowed down considerably since COVID-19, while sanitizing procedures have added an additional, heavy expense. She also notes that the migrants who have come in the past year are far more distressed than before, often relaying intense stories of violence. It’s those stories of families who’ve left behind everything that affect her the most.

“I’ve been fortunate enough to understand the world crisis and experience it,” she says. “But it kind of balances my life. We can always live in crisis with these types of positions, but we always need to find the good.”

In the Laredo area, border wall contracts have officially been canceled by the Biden administration, but when local violence against migrants is multifaceted, it’s difficult to predict how things will change. In the meantime, shelters have offered much-needed respite on both sides of the border through the empathy and compassion of the workers, whether working with limited resources or against the unpredictable drug war. The significance of the shelters’ efforts can’t be overstated.

After describing the tiring journey on bus and foot with her 3-year-old, all the way from Guatemala to the U.S., "Maria" (name altered for safety) was asked what she thought of being in the Laredo shelter.

“Paradise,” she laughed, then said it again: “Paradise."